Two days ago I published an article about people who have been harmed by welfare sanctions because they were chronically ill. Two of those people died as a consequence of actions taken by the Department for work and Pensions – see Welfare sanctions are killing people with chronic illnesses.

Several studies over the last few years have found there no evidence that benefit sanctions ‘help’ claimants find employment, and most have concluded that sanctions have an extremely detrimental impact on people claiming welfare support.

However, the Conservatives still insist that benefit conditionality and sanctions regime is ‘helping’ people into work.

Yesterday, an important study was published, which warned what many of us have known for a long time – that sanctions are potentially life-threatening. The authors of the study warn that sanctioning is “ineffective” and presents “perverse and punitive incentive that are detrimental to health”.

The study – Where your mental health just disappears overnight – drew on an inclusive and democratic qualitative methodology, adding valuable insight as well as empirical evidence that verifies that sanctions are harmful, life-threatening and do not work as a positive incentive to ‘help’ people into work. The authors’ conclusions further validate the wide and growing consensus that sanctions should be completely halted.

The researchers say that benefits sanctions and conditions are simply pushing disabled people further from employment as well as damaging their health.

The research was carried out jointly by the University of Essex and Inclusion London, and it was designed to investigate the experiences of people claiming the Work Related Activity (WRAG) component of Employment and Support Allowance (ESA).

The authors of the report are: Ellen Clifford of Inclusion London, Jaimini Mehta, a Trainee Clinical Psychologist at the University of Essex, Dr Danny Taggart, Honorary Clinical Psychologist and Dr Ewen Speed, both from School of Health and Social Care, also at the University of Essex.

WRAG claimants are deemed suitable for some work related activity and failure to engage can lead to ESA payments being cut or ‘sanctioned’. Under Universal Credit, the ESA WRAG is being replaced by the Limited Capability for Work group (LCW). The ESA Support Group is replaced by the Limited Capability for Work Related Activity group (LCWRA).

The research team found that all of the participants in the study experienced significantly detrimental effects on their mental health. The impact of sanctions was life threatening for some people.

For many, the underlying fear from the threat of sanctions meant living in a state of constant anxiety and fear. This chronic state of poor psychological welfare and constant sense of insecurity caused by the adverse consequences of conditionality can make it very difficult for people to engage in work related activity and was made worse by the extremely unpredictable way conditionality was applied, leaving some participants unsure of how to avoid sanctions. The researchers concluded that conditionality is an ineffective psychological intervention. It does not work as the government have claimed.

The research report and findings were launched at an event in Parliament hosted by the cross-bench peer Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson.

Ellen Clifford, Campaigns and Policy Manager at Inclusion London, said: “This important research adds to the growing weight of evidence that conditionality and sanctions are not only harmful to individuals causing mental and physical negative impacts, but are also counter-productive in their aim of pushing more disabled people into paid work.

“Universal Credit, which is set to affect around 7 million people with 58% of households affected containing a disabled person, will extend and entrench conditionality.

“This is yet another reason why the roll out of Universal Credit must be stopped and a new system designed based on evidence based approaches and co-produced with disabled people and benefit claimants.”

The results also showed that participants wanted to engage in work and many found meaning in vocational activity. However, the WRAG prioritised less meaningful tasks.

In addition, it was found that rather than ‘incentivising’ work related activity, conditionality meant participants were driven by a range of behaviourist “perverse and punitive incentives”, being asked to engage in activity that undermined their self-confidence and required them to understate their previous achievements.

Other themes that emerged during the study included more negative experiences of conditionality, which included feeling controlled, a lack of autonomy and work activities which participants felt were inappropriate or in conflict with their personal values.

The government have claimed that generous welfare creates ‘perverse incentives’ by making people too comfortable and disinclined to look for work. However, international research has indicated that this isn’t true. One study found that generous welfare actually creates a greater work ethic than less generous provision.

Dr Danny Taggart, Lecturer in Clinical Psychology at the University of Essex, said: “Based on these findings, the psychological model of behaviour change that underpins conditionality and sanctioning is fundamentally flawed.

“The use of incentives to encourage people to engage in work related activity is empirically untested and draws on research with populations who are not faced with the complex needs of disabled people.

“The perverse and punitive incentives outlined in this study rendered participants so anxious that they were paradoxically less able to focus on engagement in vocational activity.

“More research needs to be undertaken to understand how to best support disabled people into meaningful vocational activity, something that both the government and a majority of disabled people want.

“This study adds further evidence to support any future research being undertaken in collaboration with disabled people’s organisations who are better able to understand the needs of disabled people.”

Participants in the study commented on some of the perverse incentives: “The new payments for ESA from this year are £73 a week as opposed to £102. Well if you’re on £102 a week because you’ve been on it for longer than 6 or 12 months and you know if you go back to work and it turns out you’re not well enough to carry on then you’re coming back at the new rate of £73 per week. That’s going make you more cautious and its counter-productive and it increases the stress.” (Daniel).

“After 13 weeks I have to go and put a new claim in. After 13 weeks if the job doesn’t last, or if I get made redundant, or if I get terminated or the contract stops, I then have to go into starting all over again. Reassessment etc. So, I’m worse off.” (Dipesh).

Another form of perverse and punitive incentive arises because qualifications are regarded as an impediment to employment, not an asset; “So when the Job Centre says to you, you should remove your degree from your CV because they don’t want you to be over qualified when you apply for the jobs they give… The impact on your feeling of self-worth… They told me to remove it and if I didn’t I would be punished and would be sanctioned… This is the way that the Job Centre chip away at your confidence and all those sorts of things.” (Charlie).

The report discusses the stark impact of sanctions, described by ‘Charlie’. The authors say: “We include a fuller narrative in this case as it incorporates a number of the themes that came up for the sample as a whole – the perverse and punitive incentives and double binds involved in the WRAG, the mental health crises caused by Conditionality and Sanctioning, and how these pushed people further away from employment.

Charlie explains: “It became a really stressful time for me… we didn’t have a foodbank that was open regularly so I didn’t have that as an option… So, what I was doing instead, because quite quickly my electricity went out… So, all my food was spoilt that was in the freezer. I managed to last for another 5-6 days of food from stuff that I had in the house. So, after that I started to go, I was on a work programme but was never called in. So, I’d go in anyway and there were oranges and apples in a fruit bowl, so I would just go in there and steal the oranges and bananas so I would have something to eat. Then they finally made a decision that I was going to be sanctioned… And there was this image which will probably stay with me for the rest of my life.

“On Christmas day I was sat alone, at home just waiting for darkness to come so I could go to sleep and I was watching through my window all the happy families enjoying Christmas and that just blew me away. And I think I had a breakdown on that day and it was really hard to recover from and I’m still struggling with it. And it was only my aunt,

I’ve got an aunt in Scotland, every year she sends me £10 for my birthday and £10 for Christmas. And so on the Saturday after Christmas, the first postal day, I received £20 from her and so then I could buy some electricity and food. I was then promptly sick because I’d gorged myself, because I ate too quickly.”

The authors add Charlie’s description of a meeting with the same advisor who had sanctioned him following the Christmas break and how it has affected him since: “So finally, when new year had ended and I had to go back and sign with that same woman who had sanctioned me. She said that being sanctioned had shown her that I didn’t have a work ethic. Now I’d been working pretty much solidly since I was 16 and it was only out of redundancy that I was out of work…

“The problem I had with that was the woman who sanctioned me was in the same place and it made me extremely nervous. I now have a problem going into the Job Centre because I literally start shaking because of the damage that the benefit sanction did to me… So yeah that was part, the sanction was one of the reasons that triggered the mental health and problems I’m having now…it was awful and I ended up trying to commit suicide… to me that was the last straw and I went home and I just emptied the drawer of tablets or whatever and I ended up in A&E for a couple of days after they’d pumped my stomach out.” (Charlie).

The report also echoes a substantial part of my own work in critiquing the behaviourist thinking that underpins the idea of sanctions. The ideas of conditionality and sanctions arose from Behavioural Economics theories. (See also my take on the hostile environment created by welfare policy and practices that are based on behaviourism and a language of neoliberal ‘incentives’ – The connection between Universal Credit, ordeals and experiments in electrocuting laboratory rats).

The study finds “no evidence to support the use of this modified form of Behavioural Economics in relation to Disabled people”.

The report authors say: “These models of behaviour change are not applicable for Disabled People accessing benefits. The incentives offered by Conditionality and Sanctioning involve threats of removing people’s ability to access basic resources. This induces a state of anticipatory fear that negatively impacts on their mental health and renders them less able to engage in work related activity.”

The report concludes that the DWP should end sanctions for disabled people. The authors recommended that the DWP works inclusively with disabled groups to come up with a better system.

It was once a common sense view that if you remove people’s means of meeting basic survival needs – such as for food, fuel and shelter – their lives will be placed at risk. Welfare support was originally designed to cover basic needs only, so that when people faced difficult circumstances such as losing their job, or illness, they weren’t plunged into absolute poverty. Now our social security does not adequately meet basic survival needs. It’s become acceptable for a state to use the threat and reality of hunger and destitution to coerce citizens into conformity.

Why sanctions and conditionality cannot possibly work

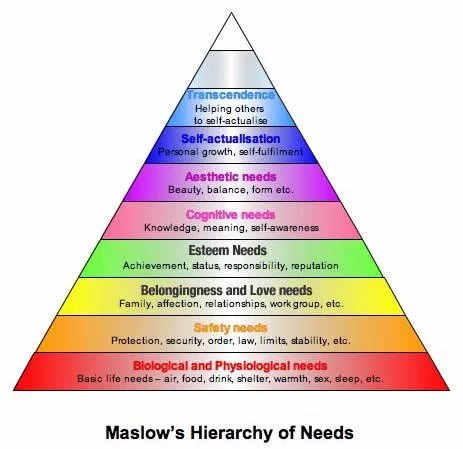

One fundamental reason why sanctions can never work as the government has claimed, to ‘incentivise’ people into work centres on Abraham Maslow’s groundbreaking work on human needs. Maslow highlights that people can’t fulfil their ‘higher level’ psychosocial needs when their survival needs are compromised. When people are reduced to a struggle for survival, that takes up all of their motivation and becomes their only priority.

The Minnesota Starvation experiment verified Maslow’s theory.

One of the uniquely important features of Britain’s welfare state was the National Insurance system, based on the principle that people establish a right to benefits by making regular contributions into a fund throughout their working lives. The contribution principle has been a part of the welfare state since its inception. A system of social security where claims are, in principle, based on entitlements established by past contributions expresses an important moral rule about how a benefits system should operate, based on reciprocity and collective responsibility, and it is a rule which attracts widespread public commitment. National Insurance is felt intuitively by most people to be a fair way of organising welfare.

The Conservative-led welfare reforms had the stated aim of ensuring that benefit claimants – redefined as an outgroup of free-riders – are entitled to a minimum income provided that they uphold responsibilities, which entail being pushed into any available work, regardless of its pay, conditions and appropriateness. The government claim that sanctions “incentivise” people to look for employment.

Conditionality for social security has been around as long as the welfare state. Eligibility criteria, for example, have always been an intrinsic part of the social security system. For example, to qualify for jobseekers allowance, a person has to be out of work, able to work, and seeking employment.

But in recent years conditionality has become conflated with severe financial penalities (sanctions), and has mutated into an ever more stringent, complex, demanding set of often arbitrary requirements, involving frequent and rigidly imposed jobcentre appointments, meeting job application targets, providing evidence of job searches and mandatory participation in workfare schemes. The emphasis of welfare provision has shifted from providing support for people seeking employment to increasing conditionality of conduct, in a paternalist attempt to enforce particular patterns of behaviour and to monitor claimant compliance.

The Conservatives have broadened the scope of behaviours that are subject to sanction, and have widened the application of sanctions to include previously protected social groups, such as ill and disabled people, pregnant women and lone parents.

Ethical considerations of injustice and the adverse consequences of welfare sanctions have been raised by politicians, charities, campaigners and academics. Professor David Stuckler of Oxford University’s Department of Sociology, amongst others, has found clear evidence of a link between people seeking food aid and unemployment, welfare sanctions and budget cuts, although the government has, on the whole, tried to deny a direct “causal link” between the harsh welfare “reforms” and food deprivation. However, a clear correlation has been established.

A little more about behavioural economics and welfare policy

I’ve written extensively and critically about how Behavioural Economics and the ‘behaviourist turn’ has become embedded in welfare policies and administration.

The use of targeted citizen behavioural conditionality in neoliberal policy making has expanded globally and is strongly linked to the growth in popularity of behavioural economics theory (“nudge”) and the New Right brand of “libertarian paternalism.”

Reconstructing citizenship as highly conditional stands in sharp contrast to democratic principles, rights-based policies and to policies based on prior financial contribution, as underpinned in the social insurance and social security frameworks that arose from the post-war settlement.

The fact that the poorest citizens are being targeted with theory-based “interventions” also indicates discriminatory policy, reflecting traditional Conservative class-based prejudices. It’s a very authoritarian approach to poverty and inequality which simply strengthens existing power hierarchies, rather than addressing the unequal distribution of power and wealth in the UK.

Some of us have dubbed this trend neuroliberalism because it serves as a justification for enforcing politically defined neoliberal outcomes. A hierarchical socioeconomic organisation is being shaped by increasingly authoritarian policies, placing the responsibility for growing inequality and poverty on individuals, sidestepping the traditional (and very real) structural explanations of social and economic problems, and political responsibility towards citizens.

Such a behavioural approach to poverty also adds a dimension of cognitive prejudice which serves to reinforce and established power relations and inequality. It is assumed that those with power and wealth have cognitive competence and know which specific behaviours and decisions are “best” for poor citizens.

Apparently, the theories and “insights” of cognitive bias don’t apply to the theorists applying them to increasingly marginalised social groups. No one is nudging the nudgers. Policy has increasingly extended a neoliberal cognitive competence and decision-making hierarchy as well as massive inequalities in power, status and wealth.

It’s interesting that the Behavioural Insights Team have more recently claimed that the state using the threat of benefit sanctions may be “counterproductive”. Yet the idea of increasing welfare conditionality and enlarging the scope and increasing the frequency of benefit sanctions originated from the behavioural economics theories of the Nudge Unit in the first place.

The increased use and rising severity of benefit sanctions became an integrated part of welfare conditionality in the Conservative’s Welfare Reform Act, 2012. The current sanction regime is based on a principle borrowed from behavioural economics theory – an alleged cognitive bias we have called “loss aversion.”

It refers to the idea that people’s tendency is to strongly prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains. The idea is embedded in the use of sanctions to “nudge” people towards compliance with welfare rules of conditionality, by using a threat of punitive financial loss, since the longstanding, underpinning Conservative assumption is that people are unemployed because of alleged behavioural deficits and poor decision-making. Hence the need for policies that “rectify” behaviour.

I’ve argued elsewhere, however, that benefit sanctions are more closely aligned with operant conditioning (behaviourism) than “libertarian paternalism,” since sanctions are a severe punishment intended to modify behaviour and restrict choices to that of compliance and conformity or destitution. At the very least this approach indicates a slippery slope from “arranging choice architecture” in order to “support right decisions” that assumed to benefit people, to downright punitive and coercive policies that entail psycho-compulsion, such as sanctioning and mandatory workfare.

For anyone curious as to how such tyrannical behaviour modification techniques like benefit sanctions arose from the bland language, inane, managementspeak acronyms and pseudo-scientific framework of “paternal libertarianism” – nudge – here is an interesting read: Employing BELIEF: Applying behavioural economics to welfare to work, which is focused almost exclusively on New Right small state obsessions. Pay particular attention to the part about the alleged cognitive bias called loss aversion, on page 7.

And this on page 18:

“The most obvious policy implication arising from loss aversion is that if policy-makers can clearly convey the losses that certain behaviour will incur, it may encourage people not to do it”.

And page 46:

“Given that, for most people, losses are more important than comparable gains, it is important that potential losses are defined and made explicit to jobseekers (eg the sanctions regime)”.

The recommendation on that page:

“We believe the regime is currently too complex and, despite people’s tendency towards loss aversion, the lack of clarity around the sanctions regime can make it ineffective. Complexity prevents claimants from fully appreciating the financial losses they face if they do not comply with the conditions of their benefit”.

The paper was written in November 2010, prior to the Coalition policy of increased conditionality and the extended sanctions element of the Conservative-led welfare reforms in 2012.

The Conservatives duly “simplified” sanctions by extending them in terms of severity and increasing the frequency of use. Sanctions have also been extended to include previously protected social groups, such as lone parents, sick and disabled people.

Unsurprisingly, none of the groups affected by conditionality and sanctions were ever consulted, nor were they included in the design of the government’s draconian welfare policies.

The misuse of psychology by the government to explain unemployment (it’s claimed to happen because people have the “wrong attitude” for work) and as a means to achieve the “right” attitude for job readiness. Psycho-compulsion is the imposition of often pseudo-psychological explanations of unemployment and justifications of mandatory activities which are aimed at changing beliefs, attitudes and disposition. The Behavioural Insights Team have previously propped up this approach.

Techniques of neutralisation

It is unlikely that the government will acknowledge the findings of the new study which presents further robust evidence that unacceptable, punitive welfare policies are causing distress, fear, anxiety, harm, and sometimes, death.

To date, we have witnessed ministers using techniques of neutralisation to express faux outrage and to dismiss legitimate concerns and valid criticism of their policies and the consequences on citizens as “scaremongering”.

It isn’t ‘scaremongering’ to express concern about punitive policies that are targeted to reduce the income of social groups that are already struggling because of limited resources, nor is it much of an inferential leap to recognise that such punitive policies will have adverse consequences.

Political denial is oppressive – it serves to sustain and amplify a narrow, hegemonic political narrative, stifling pluralism and excluding marginalised social groups, excluding qualitative and first hand accounts of citizen’s experiences, discrediting and negating counternarratives; it sidesteps democratic accountability; stultifies essential public debate; obscures evidence and hides politically inconvenient, exigent truths.

Research has frequently been dismissed by the Conservatives as ‘anecdotal’. The government often claims that there is ‘no causal link’ established between policies and harm. However, denial of causality does not reduce the probability of it, especially in cases where a correlation has been well-established and evidenced.

The government have no empirical evidence to verify their own claims that their ideologically-driven punitive policies do not cause harm and distress, while evidence is mounting that not only do their policies cause harm, they simply don’t work to fulfil their stated aim.

—

You can read the new research report from Inclusion London and the University of Essex in full here.

Related

DWP sanctions have now been branded ‘life-threatening’

Exclusive: DWP Admit Using Fake Claimant’s Comments In Benefit Sanctions Leaflet

Benefit Sanctions Can’t Possibly ‘Incentivise’ People To Work – And Here’s Why

Nudging conformity and benefit sanctions

Work as a health outcome, making work pay and other Conservative myths and magical thinking

I don’t make any money from my work. But you can make a donation if you like, to help me continue to research and write free, informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.

Reblogged this on Britain Isn't Eating!.

LikeLike

As mentioned above the DWP would sanction someone if they didn’t lie about their qualifications?!! As well as the cruel punitive system this is a grotesque twist on any sense of moral code.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on michaelsnaith.

LikeLike

aktion t4 hay but then this government doesn’t listen doesn’t stop its course its culling the stock through benefits denial its beyond a doubt a cruel regime and they have learned from history yet we had a system that worked it was called social security yet unerversual credits is just a whip to beat the peasants with not there to help them one bit its a joke that rtu ids got away with resetting it hiding away the billions wasted on it yet people should be asking how much would it have been if every claimant paid you’d find that the billions wasted would have coverted that and billions over there the tory failed failed their people failed their moral commitments to society

LikeLike

I suspect the Tories know exactly what the effects of their cruel, nasty and vindictive policies are, and they just don’t care.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Me too

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Christopher John Ball and commented:

Again, as with anything Kitty writes, please read and share – the work she puts into these pieces is amazing and she deserves our thanks and support.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have said a lot of this for years but didnt have means to type it or the concentration, another thing that needs done is looking at how the system empowers other over others ie dwp, atos staff and the public who have been empowered further to crush the spirits of claimant and sick and disabled citizens. and the state of the jobs market im considering after my travel pass petition to use my time to write a book on this from a personal perspective of being an esa support group member who has been terrified of being forced into the wrag for the reasons you mention

LikeLike

I was put in the WRAG first and couldn’t keep any appointments because I was so ill and on chemotherapy. Now I am finally in the support group, but live in fear that another assessment will see me moved back to the WRAG.

You should write a book, would love to read it Maria

LikeLike