The Manchester Observer was a short-lived non-conformist Radical newspaper based in Manchester, England. Its radical agenda led to an invitation to Henry “Orator” Hunt to speak at a public meeting in Manchester. The Peterloo massacre and the shutdown of the newspaper resulted from that Public Meeting.

By 1819, the allocation of Parliamentary constituencies did not reflect population distribution. The major urban centres of Manchester, Salford, Bolton, Blackburn, Rochdale, Ashton-under-Lyne, Oldham and Stockport, had a combined population of almost one million. They were represented only by their county MPs. Lancashire was represented by two members of parliament: John Blackburne of Hale Hall and Edward Smith Stanley, (Lord Stanley). Lord Stanley was a Conservative Whig and member of the “Derby Dilly” – a breakaway group of Conservative Whigs. The name derives from the family title “Earl of Derby” and the name of a stagecoach: the “Diligence” or “Dilly”; The title was bestowed on the Group by Irish Nationalist Leader Daniel O’Connell in a scathing reference to an erratic coach, with Stanley driving the horses.

It was quickly picked up by others, and the name stuck. Stanley’s reputation was as the “Prince Rupert of Debate”: leading his followers to attack but unable to rally them afterwards. As a result, it was difficult to estimate the number of MPs who were actually part of the ‘Dilly’. But the name did highlight the turmoil of the Ruling Classes. Change was very much in the air.

Both Blackburne and Stanley were Oxford educated Landowners whose families had “been in politics” for some time and were not liking the change. Not the Cooperativism and Utopian Socialism of one time Manchester resident Robert Owen – Pioneer of the Cooperative Movement and member of the Manchester Board of Health. As Whigs they were aware of the rising demands of the emerging Working Class. There was something in the air.

Indeed, in 1820, The Radical War burst out in Scotland when A Committee of Organisation for Forming a Provisional Government put placards around the streets of Glasgow late on Saturday the first of April, calling for an immediate national strike. By the third of April there was a strike.

Work stopped over a wide area of central Scotland including Stirlingshire, Dunbartonshire, Renfrewshire, Lanarkshire and Ayrshire, with an estimated total of around 60,000 stopping work, particularly in weaving communities. Eighty eight men were charged with treason. The leaders – Andrew Hardie and John Baird – were hanged and beheaded. The last beheadings in the British Isles.

The 1819 Peterloo Massacre was normal, not exceptional.

Voting, in 1819, was restricted to the adult male owners of freehold land with a rateable value greater than forty shillings. The equivalent of a rateable value of about £172 as of 2018, which equates, approximately, to owning a Freehold property worth £172,000. The amounts are approximations as the Rateable Value was largely abolished with the introduction of the Poll Tax of 1990. This property qualification resulted in very few people having the Vote. Those who did have the vote numbered around two percent of the population, and, in Lancashire the number was even lower. When 60,000 people turned out to hear Orator Hunt talk, they outnumbered the voting population for the whole of Lancashire.

The imbalance of power was not simply between Men and Women but between Rich and Poor. Indeed, Radicals were demanding that Women get the Vote. Which “moderates” saw as a step too far. Indeed Women – over thirty, of a certain class – only got the Vote after violent confrontation with the Liberals – under Asquith – and Moderates in 1918: almost a century after Orator Hunt stated that Women, who were single, tax paying and of sufficient property should be permitted to vote.

Equality of voting rights only really came about with the 1928 Representation of the People Act. The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 only allowed propertied women to vote and almost all men. The Franchise for all Working Class Adults has only really existed for about ninety years. The Electoral Register for Local and National Elections only became the same register in 1949 and the voting age fixed at 18 in 1969. Every step of the way was fought for.

In 1819 votes in Lancashire could only be cast at the county town of Lancaster, by a public spoken declaration at the hustings. There was no Secret Ballot. Britain’s first secret ballot box, which was used in Pontefract in 1872, was mandated by the Ballot Act of 1872. The Liberal candidate, H.C. Childers was elected MP for the town and the Returning Officer announced the result of the secret ballot in the Town Hall after the votes had been counted.

In 1819, the vote was cast by standing up in public and announcing for whom you cast your vote. The Returning Officer would then record the cast vote. This was of much concern to Chartists who saw the affront to democracy in people being influenced – by drunkenness or threats – at the hustings. Indeed, the specific Electoral Offence of “treating” derives from the practice of candidates providing food and drink at the hustings to induce a favourable vote.

The first automatic secret ballot box was built and patented in Merthyr Tydfil by a former iron puddler, turned grocer, William Gould. Gould was disparaged as a “Chartist Lip” – who served as a Poor Law Guardian – but understood secret ballots prevented industrialists and landowners having influence at the ballot box. The principle behind his ballot box was that each voter had a token and each candidate a ballot box. The voter inserted the token into the box of their choice and the vote was registered onto a clock face on the box. This would reduce the potential for intimidation. Despite campaigning, his idea was not adopted. In terms of secrecy of the vote, it was a huge step up from the spoken declaration at the hustings.

The problem of getting to Lancaster is that most working people would need to walk. Using modern roads, the hike would be about seventeen hours each way at a brisk pace. In addition, time would be needed to be taken away from working; food would need to be carried and accommodation organised. The large scale movement of people was a terrifying prospect for Justices and Politicians and Landowners. An election in which there was Universal Adult Suffrage would have been revolutionary with hundreds of thousands of people moving to Lancaster to cast a vote.

The logistics of voting, alone, would have extended the ballot to weeks if not months. Which would increase the time away from work and the food required and, in no uncertain terms, disrupt the entire economy. The Rotten Boroughs were not simply a symptom of corruption but of the collapse of the practical political and economic life of the Country.

Stockport fell within the county constituency of Cheshire, with the same franchise, but with the hustings held at Chester. This would have complicated the matter further. Both Chester and Lancaster Returning Officers would be obliged to confer and coordinate. Many MPs were returned by Rotten Boroughs such as Old Sarum in Wiltshire, with one voter who elected two MPs. Dunwich in Suffolk had almost completely disappeared into the sea yet returned Members of Parliament. Closed Boroughs with more voters, dependent on a local magnate meant that more than half of all MPs were elected by boroughs under the control of a total of just 154 proprietors. This hugely disproportionate influence on Parliament of the United Kingdom drove calls for reform.

The Manchester Observer was formed by a group of radicals that included John Knight. John Saxton and James Wroe. The popularist form of articles aimed at the growing literate working-class meant that, within twelve months, it was selling 4,000 copies per week to its local audience and more further afield. By late 1819 it was being sold in most of the booming industrialised cities – Birmingham, Leeds, London, Salford – all calling for non-conformist reform of the Houses of Parliament. It was a powerful demand for Democracy to be part of life for everyone and not just the few.

Orator Hunt stated:

“The Manchester Observer is the only newspaper in England that I know, fairly and honestly devoted to such reform as would give the people their whole rights.”

The non-conformist articles, combined with a popularist style, often resulted in the main journalists of T. J. Evans, John Saxton and James Wroe constantly being sued for libel. Being found guilty, particularly for articles critical of Parliament’s structure, resulted in jail which then raised circulation. Despite its popularity, the radical agenda was seen as bad for sales by traditionalist conformist-Whig businesses. Advertising revenue remained low with only one of its 24 columns being filled by adverts. The lack of advertising meant the Observer was always in financial difficulties.

In Early 1819, Johnson, Knight and Wroe of the Manchester Observer formed the Patriotic Union Society. Leading radicals and reformists in Manchester joined the organisation, including members of the First Little Circle. The First Little Circle had formed in 1815, influenced by the ideas of Jeremy Bentham and Joseph Priestley. While the members were Unitarians, the political ideas were practical, utilitarian and resolutely reforming. Members went on to become Editors and Members of Parliament and to be involved in the Businesses of Manchester whose emerging Municipal Socialist, Cooperativist and Feminist movements would have a lasting impact on Britain.

The objective of the Patriotic Union Society was parliamentary reform both locally and, in the longer term, nationally. The Patriotic Union Society invited Henry “Orator” Hunt and Major John Cartwright to speak at a public meeting in Manchester. The national agenda of Parliamentary reform, and the local agenda to gain two Parliamentary Members for Manchester and one for Salford, were to be the subject of the speech but, to avoid the police or courts banning the meeting, the Patriotic Union Society and the Observer advertised only, “a meeting of the county of Lancashire, than of Manchester alone.”

On August 19th 1819, at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, cavalry charged into a crowd of 60,000-80,000 Men, Women and Children. As the meeting began, local magistrates called on the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to arrest Orator Hunt and those on the hustings with him. A Yeomanry charge into the crowd, knocked down a woman and killed a child before detaining Hunt. The 15th Hussars were then summoned by the Chairman of the Lancashire and Cheshire Magistrates, William Hulton. They charged with sabres drawn, killing 18 people and injuring 700 more. The Hussars had been ordered to Manchester by a panicked government who believed an insurrection was being planned on the basis of an intercepted message between the Manchester Observer’s founder – Joseph Johnson – and Orator Hunt:

“Nothing but ruin and starvation stare one in the face in the streets of Manchester and the surrounding towns, the state of this district is truly dreadful, and I believe nothing but the greatest exertions can prevent an insurrection. Oh, that you in London were prepared for it.”

The Local Magistrate, William Hulton, had the meeting declared illegal as the intention of choosing representatives without the Monarch’s Permission was seditious and a serious misdemeanour. This began a series of planned meetings and cancellations with the terms of the meeting being constantly changed to conform to the desire for Members Of Parliament and the repeated escalation of the State against the Radicals. Eventually, the Meeting was policed by six hundred of the 15th Hussars; the 88th Regiment of Foot Cavalry; two six-pounder guns from the Royal Horse Artillery unit; four hundred men of the Cheshire Yeomanry; four hundred special constables; and one hundred and twenty cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry.

The Yeomanry were described by the Manchester Observer as being, “generally speaking, the fawning dependents of the great, with a few fools and a greater proportion of coxcombs, who imagine they acquire considerable importance by wearing regimentals”.

Subsequent descriptions include, “younger members of the Tory party in arms”, and, by later historians, “the local business mafia on horseback”.

Field Marshal John Byng, 1st Earl of Strafford, rather than supervising events as he had indicated he would, spent the day at York Races – where he had two entries – and left the matter of Manchester in the hands of Guy L’Estrange.

HC Deb 24 November 1819 vol 41 cc228-301

No. 36. REPORT from Lieutenant Colonel l’Estrange, inclosed in the foregoing.

Dated Manchester, August 16, 1819, eight o’clock, P. M.

...I have, however, great regret in stating, that some of the unfortunate people who attended this meeting have suffered from sabre wounds, and many from the pressure of the crowd…

Geo. L’Estrange,

Lieut. Col. 31st regiment.

The Military rioted and massacred the Civilians; many, of whom, were wearing their Sunday Best Clothes and had marched from all around Manchester. Carrying banners and organised for a picnic. The imbalance of power was not simply political but of brute force. There were banners for Manchester Female Reform Society – Votes for Women! – “No Corn Laws”, “Annual Parliaments”, “Universal suffrage” and “Vote By Ballot”. Nothing really radical. Mary Fildes (born Pritchard) a political activist and an early suffragette was on the platform with Orator Hunt.

Mary remained a radical and was later arrested, in 1833, as a member of The Female Political Union of the Working Classes. She was arrested for distributing “pornography” – in fact contraceptive advice. The only banner to survive has the words “Liberty and and Fraternity” and “Unity and Strength” carried by Thomas Redford – who was cut down by cavalry. The crowd was dispersed in about ten minutes; but rioting was sparked as far away as Macclesfield and Oldham.

Field Marshal Byng was promoted to lieutenant general in 1825; then advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1828; advancing, again, to Commander-in-Chief of Ireland and then to the Privy Council of Ireland. He was elected as a Whig Member of Parliament for Poole in Dorset in October 1831. One of the few military men to supported the 1832 Reform Bill. His role in Peterloo never once prevented him from enjoying political power.

Wroe, as then editor of the Observer, described the incident at the Peterloo massacre. He took his headline from the Battle of Waterloo four years previously. Subsequently, Wroe wrote pamphlets entitled, “The Peterloo Massacre: A Faithful Narrative of the Events”. They sold out each print run for 14 weeks with national circulation. Saxton, having been on the hustings with Hunt, was arrested and imprisoned. He stood trial with Hunt at York Assizes.

His defence that he was present as a reporter, not participant in the hustings party, was successful. The success of his defence did not sit well with the Government. Hunt was sentenced to five years at Ilchester Jail, fined one thousand pounds and made to find two sureties of five hundred pounds having escaped the charge of High Treason.

The Observer printed an article claiming that, “something was previously arranged”, as Manchester Royal Infirmary had been emptied of patients, on the 15th of August, anticipating the massacre. That all the surgeons had been summoned to attend on 16th. The Board of the infirmary vigorously denied this. The Liverpool Government then instigated repeated prosecutions of the Manchester Observer and those associated with it. Vendors were prosecuted for seditious libel. Fifteen charges of seditious libel were brought against Wroe, his wife and his two brothers resulting in the temporarily suspension of publication. Wroe relinquished ownership of the copyright and resumed under the last proprietor of the Manchester Observer (Thomas John Evans). At trial Wroe was found guilty on two specimen charges.

The other charges against him, his wife and his brothers being given “to lie”. The charges would only lie provided the publication of “libels” ceased. Wroe was sentenced to six months imprisonment and fined £100 with a further six months, and being bound over to keep the peace for two years, to give a surety of £200 and to find two other sureties of £50 each.

The prosecuted charges related not to anything in the Manchester Observer, but to articles in Sherwin’s Weekly Political Register, which Wroe had previously sold. It was clear that the Liverpool Government wished to silence Wroe and took the most certain way of doing so. Prosecuting Richard Carlile, who had been present at Peterloo enabled prosecution on the coat tails of conviction. Carlile wrote an article on the “Horrid Massacres At Manchester”. The Government responded by closing Sherwin’s Weekly Political Register. Carlile responded by changing the name to The Republican and writing:

“The massacre… should be the daily theme of the Press until the murderers are brought to justice…. Every man in Manchester who avows his opinions on the necessity of reform, should never go unarmed – retaliation has become a duty, and revenge an act of justice.”

Carlile was then prosecuted for blasphemy, blasphemous libel and sedition and publishing material that might encourage people to hate the government; for publishing Tom Paine’s Common Sense, The Rights of Man and the Age of Reason. In October 1819 he was found guilty of the blasphemy and seditious libel and sentenced to three years which enabled Wroe to be caught up in the moral panic of atheist Republicanism and prosecuted with impunity.

The sentences were said to have been reduced because of the distressed state of the Wroes. A distress brought about by the Government but which cast the Government in a poor light. It was a delicate balance to secure an effective remedy to the power of Wroes publications. Wroes successor, Evans, was subsequently (June 1821) convicted on one charge of a seditious libel another of libelling a private individual and imprisoned for eighteen months and bound over for three years in the sum of £400 with two other sureties of £200. By then the 11 members of the first Little Circle excluding William Cowdroy Jnr. of the Manchester Gazette had helped cotton merchant John Edward Taylor found The Manchester Guardian.

The Manchester Observer had ceased publication. The Government had driven it into silence by repeated prosecution. The final editorial recommending:

“I would respectfully suggest that the Manchester Guardian, combining principles of complete independence, and zealous attachment to the cause of reform, with active and spirited management, is a journal in every way worthy of your confidence and support.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley was in Italy at the time of Peterloo. In response, Shelley wrote “The Masque of Anarchy: written on the Occasion of the Massacre at Manchester“. Because of radical press restrictions, it was not published until 1832 – the same year as The Representation of the People Act (1832).

The Act introduced a system of voter registration, to be administered by the Overseers of the Poor; and instituted a system of courts to review disputes relating to “voter qualification”. The Act limited the duration of polling to two days – formerly forty days. The reform act increased the number of people able to vote, across the country, to about 650,000 – about ten times the largest estimate of the number of people attending Peterloo.

When Shelley wrote:

“Men of England, heirs of Glory,

Heroes of unwritten story,

Nurslings of one mighty Mother,

Hopes of her, and one another;

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you –

Ye are many – they are few.”

He was writing lyrics for punk bands like The Mekons, Scritti Politti and Strike Anywhere. The radical sentiments of Peterloo never vanished regardless of how submerged they were. Indeed Shelley is claimed to be part of the inspiration for the Arab Spring, Ghandi and numerous other radical causes. The truth is closer: “A spectre is haunting Manchester – the spectre of Peterloo. All the powers of old England have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: Liberal and Tory, Johnson and Swinson, European Research Group and Big Data-spies.” To paraphrase those later journalists of the Manchester Guardian: Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx.

For a few months following Peterloo it seemed England shook, towards an armed rebellion. Abortive uprisings took place in Huddersfield and Burnley, the Yorkshire West Riding Revolt, the Cato Street conspiracy, the Cinderloo Uprising in the Coalbrookdale Coalfield, the Pentrich rising, the March of the Blanketeers, the Spa Fields, and the Radical War ll made the end of Regency Civilisation more and more vivid. The Government introduced the Six Acts, to suppress radical meetings and publications. By the end of 1820 every significant working-class radical reformer was in jail. Civil liberties were largely gone.

Two hundred years later, the Tories are again splitting and civil liberties are again being rolled back.

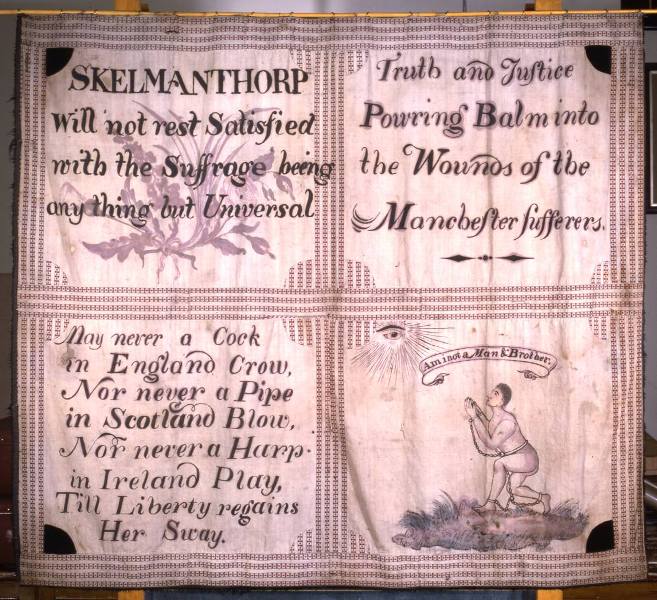

Picture: The Skelmanthorpe Flag. Anonymous.

Image © Kirklees Museums & Galleries

Reblogged this on Declaration Of Opinion.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Tory Britain!.

LikeLike

Love the flag! And the poetry too. Skelmanthorpe is in my neck of the woods. The Huddersfield area as a whole has a great history of dissent. If only we could harness it once again in this era of Oppression. Maybe we shall.

LikeLike

It seems inconceivable something similar like this could happen again in this once great country of ours (or should I say: ‘theirs?!’) But with the suppression of peoples rights through sanctions and the control of the media through right wing Barons, this idiotic ‘Brexit’ deal (benefitting the powerful and wealthy for example, I can envisage things could change quite quickly.

LikeLike

I’ve read about that massacre. That was a decade after Thomas Paine’s death.

On his last visit to England in 1792, he tried to incite protest and revolt or at least to open up public debate. But the English public either wasn’t ready for it or they were too propagandized at the time or something.

Obviously, public outrage was building up. I’m sure there were plenty of people who agreed with Paine when he was still alive but were too afraid to speak up. The British government back then didn’t tolerate much free speech.

LikeLike