The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) said an analysis of all the changes to tax, social security and public spending since the Conservatives came to power in 2010 showed the poorest citizens have been hit hardest by tax, social security and public spending reforms and are set to lose at least 10% of their income.

Ahead of next week’s budget, the Commission has published its independent report on the impact that changes to all tax, social security and public spending reforms from 2010 to 2017 will have on people by 2022.

Undertaken as a “cumulative impact assessment”, the Commission’s report, which looks at the impact the reforms have had on various groups across society, highlights that those political decisions will affect some groups more than others:

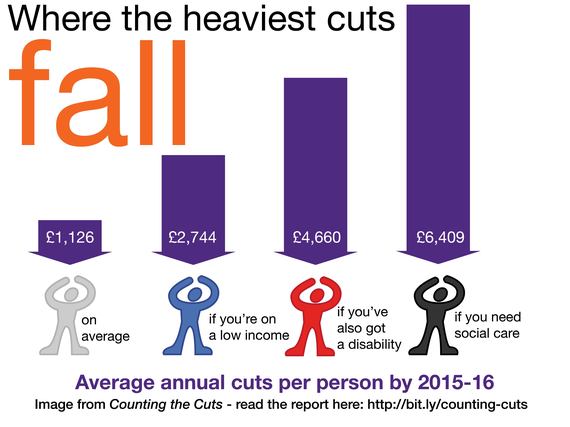

- black households will face a 5% loss of income (more than double the loss for white households)

- families with a disabled adult will see a £2,500 reduction of income per year (this is £1,000 for non-disabled families

- families with a disabled adult and a disabled child will face a £5,500 reduction of income per year (again, compared to £1,000 for non-disabled families)

- lone parents will struggle with a 15% loss of income (the losses for all other family groups are between 0 and 8%)

- and women will suffer a £940 annual loss (more than double the loss for men)

- the biggest average losses by age group, across men and women, are experienced by the 65 to 74 age group (average losses of around £1,450 per year) and the 35 to 44 age group (average losses of around £1,250 per year).

The government have persistently claimed that conducting a cumulative impact assessment of their “reforms” is “too difficult”.

David Isaac, of the EHRC, says: “We have encouraged the government to carry out this work for some time, but sadly they’ve refused. We have shown that it is possible.”

Previously, the Women’s Budget Group estimated that by 2020 women will shoulder 85% of the burden of the government’s changes to the tax and benefits system – with low-income black and Asian women paying the highest price.

The Centre for Welfare Reform calculated that disabled people are being hit nine harder than the rest of the population. These organisations managed to carry out cumulative impact assessments, and without the generous funding that the government has at their disposal. This demonstrates that there is a difference between finding something “difficult” to undertake, and not actually wanting to undertake the task, while making glib excuses to avoid doing so.

Public policies are expressed political intentions regarding how our society is organised and governed. They have calculated social and economic aims and consequences. Governments generally monitor the impact of their policies. The Conservatives have refused to monitor the impact of their draconian welfare policies because they knew in advance that they are discriminatory.

Austerity policies target already economically marginalised groups, cutting their incomes further. It’s not plausible that ministers were unaware that this would lead to further economic disadvantage of those groups, while widening social inequality and increasing poverty.

While the poorest citizens are set to lose nearly 10% of their incomes, a minority of the wealthiest citizens will lose barely 1%, yet the government claim that inequality has “reduced.” Despite the claims that “We’re all in it together” and “we want to help tjose people “just about managing”, it’s clear that Conservative policies are completely detached from public interests and needs. Conservative austerity policies are designed and intended to intentionally discriminate aginst the very poorest citizens.

It is against the law to discriminate against socially protected groups – including on the grounds of ethnicity, gender, age and disability. The government’s traditional ideological prejudices, which have been clearly expressed in their socioeconomic policies, have brought about:

- the less favourable treatment of groups with protected characteristics

- the targeting of some social groups disproportionately with austerity policies that extend direct discrimination, leaving people with protected characteristics at an unfair disadvantage

Prices, as measured by official inflation figures, are nearly 14% higher now than they were in 2010, although Unison say that between the start of 2010 and the close of 2015, the cost of living, as measured by the Retail Prices Index, rose by a total of 19.5%. This creates even further hardship for those people already targeted by Conservative austerity cuts.

Traditional Conservative prejudices, which have ultimately led to economic marginalisation, disadvantage and stigmatisation of some social groups

David Isaac, the Chair of the EHRC, which is responsible for making recommendations to government on the compatibility of policy and legislation with equality and human rights standards, warned of a “bleak future”.

Isaac said: “The Government can’t claim to be working for everyone if its policies actually make the most disadvantaged people in society financially worse off. We have encouraged the Government to carry out this work for some time, but sadly they have refused. We have shown that it is possible to carry out cumulative impact assessments and we call on them to do this ahead of the 2018 budget.

“If we want a prosperous and, in line with the Prime Minister’s vision, a fair Britain that works for everyone, the Government must come clean and provide a full and cumulative impact analysis of all current and future tax and social security policies. It is not enough to look at the impact of individual policy changes. If this doesn’t happen those most in need will face an extremely bleak future.”

The Commission is calling on the Government to:

- commit to undertaking cumulative impact assessments of all tax and social security policies ahead of the 2018 budget

- reconsider existing policies that are contributing to negative financial impacts for those who are most disadvantaged

- implement the socio-economic duty from the Equality Act 2010 so public authorities must consider how to reduce the impact of socio-economic disadvantage of people’s life chances (the Conservatives edited the Labour party’s original version of Equality Act and removed this duty before implementing it).

The assessment undertaken by the EHRC considered changes to income tax, national insurance contributions, indirect taxes (VAT and excise duties), means-tested and non-means-tested social security benefits, tax credits, universal credit, national minimal wage and national living wage.

See also:

Austerity is “economic murder” says Cambridge researcher

The Paradise Papers, austerity and the privatisation of wealth, human rights and democracy

From 2013 – Follow the Money: Tory ideology is all about handouts to the wealthy that are funded by the poor

I don’t make any money from my work. I am disabled because of illness and have a very limited income. I don’t have a plasma TV or Sky. I do eat a lot of porridge, though. Successive Conservative chancellors have left me in increasing poverty. But you can help by making a donation to help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.

On Monday, disabled representatives from disability organisations across England, Scotland and Wales presented reports to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Geneva. It is now eight years since the UK ratified the UNCRPD with cross-party support and this is the committee’s first full examination of the UK’s performance.

So how are we doing? The government is fond of claiming that the UK is a “world leader” on disability rights. Superficially, this claim remains fairly accurate. We have the most comprehensive and proactive equality law anywhere in the world; social care legislation and practice that embodies the principle of choice and control; a social security system that claims to recognise the extra costs of disability; and law and regulations to advance accessibility.

It is important to remind ourselves of what disabled people have achieved over the past 30-40 years of disability rights activism, as we have charted our journey from objects of care and charity to becoming active, contributing citizens. But any assessment of progress cannot be confined solely to what we now have, or where we were in the past. And judging by the UK’s direction of travel, the government’s claim of world leadership quickly unravels: we are seeing big cuts to services and watering down of rights and opportunities of disabled people.

Last year, I served on the House of Lords select committee, reviewing the impact of the Equality Act on disabled people. We found that this government’s deregulatory zeal and spending cuts significantly undermined the intended effect of the act. Employment tribunal fees, legal aid cuts and loss of advice services have put the act’s protection beyond the reach of most disabled people. And colossal cuts to the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s budget have left the act under-promoted and unenforced.

The UK’s mental health and mental capacity laws fail to comply with the CRPD, which stipulates that disability cannot be grounds for denying people equal recognition before the law or for depriving people of their liberty. Yet in England, there has been a 10% rise in detention each year for the past two years. More than half of these cases related to people with dementia, and a significant minority to adults with learning disabilities. The sanctioned use of restraint, seclusion and anti-psychotic medication remains commonplace on mental health and learning disabilty wards, violating people’s rights to physical and mental integrity and to live free from torture, inhuman or degrading treatment.

NHS benchmarking data revealed that there were 9,600 uses of restraint during August 2015 in mental health wards in England, while the Learning Disability Census 2015 found that one-third of patients with a learning disability were subject to the use of restraint in 2015-16.

Unexpected deaths of mental health in-patients, or those cared for at home in England, are up by 21% yet, unlike deaths in police, prison or immigration detention, there is no system of independent investigation. Since 2011, hospitals in England have investigated just 222 out of 1,638 deaths of patients with learning disabilities. Among deaths they classed as unexpected, hospitals inquired into just over a third.

The Care Act fails to ensure disabled people’s right to independent living, and swingeing cuts in health, social care and benefits are eroding the availability of support and people’s right to exercise choice and control. Disabled people are confronting the spectre of re-institutionalisation as councils and clinical commissioning groups limit the amount they spend on individual packages of support.

The UN disability rights committee has already reported on the negative impact of the UK’s measures to cut social security spending. Yet further disability benefit cuts continue to be implemented and the extension of punitive sanctions to those hitherto assessed as unable to work is being proposed on the back of declining investment in employment support.

“Nothing about us without us” is the international motto of the disability rights movement, but there is little evidence of disabled people being involved in policy development. The last 10 years have seen the proportion of public appointees with a self-declared disability halve in number, while helpful measures to support more disabled people into politics, such as the Access to Elected Office Fund, have been suspended in England.

Advancing the rights of disabled people requires good leadership to establish coherence and coordination in Whitehall, and in devolved and local government. The Office for Disability Issues was set up for this very task, but has become a shadow of its former self. But in Wales and Scotland, things are more positive, with the convention firmly embedded in policy and strategy.

If the UK wants to maintain the mantle of world leader on disability rights, it must see the forthcoming examination as an opportunity to listen and take stock. If it fails to do so, current and future generations of disabled people face the slow, inexorable slide back towards social death once again.