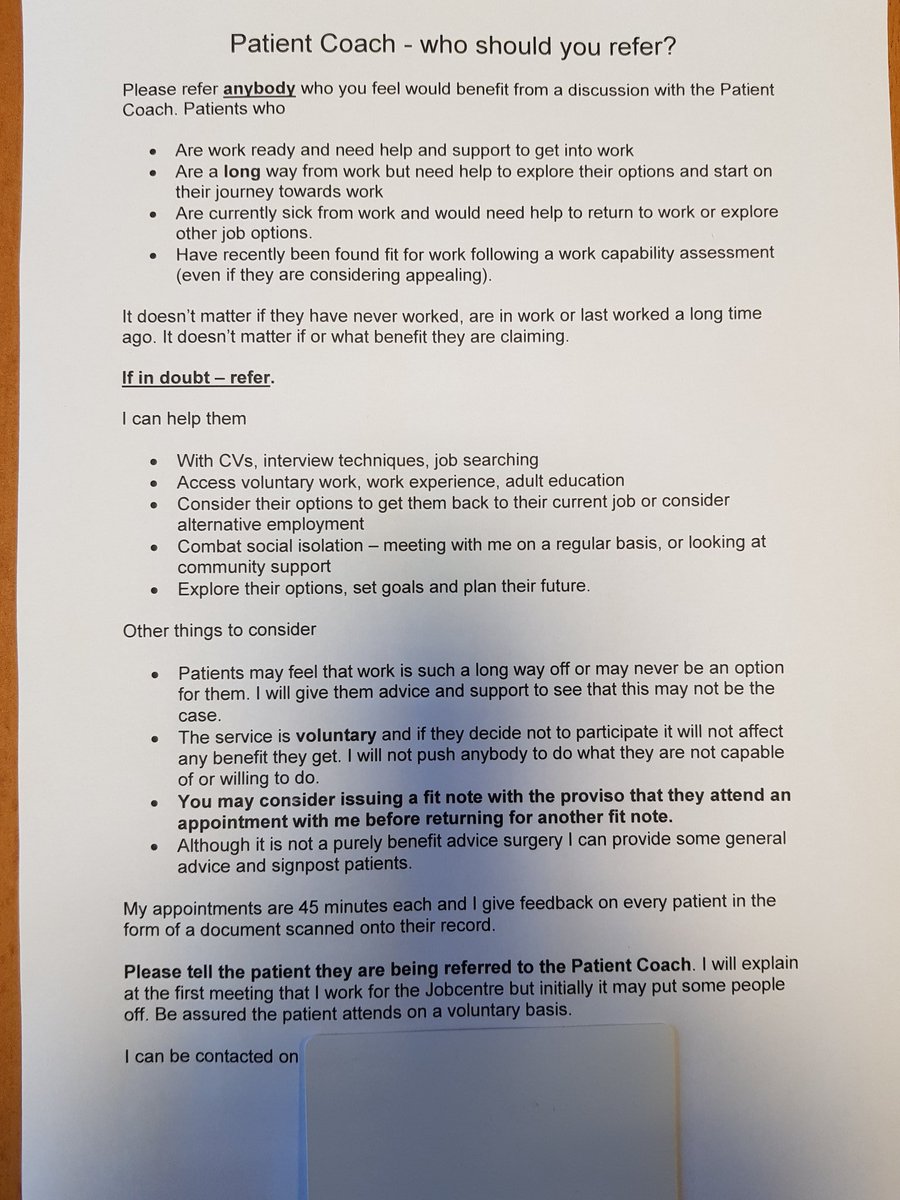

Thanks to @CarolePavlova76 for the copy of a patient work coach letter to GPs.

One of the most worrying comments on the above letter is that despite claiming the work coach service is voluntary, and that if a patient refuses to engage “it won’t affect any benefit they get”, the letter then goes on to suggest that doctors may consider the issuing of subsequent fit notes conditional (“with the proviso that”) on their patient attending a meeting with the work coach. That one sentence simply makes a mockery of the claim that patient engagement with work coaches is voluntary.

Illnesses don’t respond to provisos or caveats. People don’t suddenly recover when the Department for Work and Pensions decides that they are fit for work. When job centre staff tell GPs to stop issuing sick notes to patients it can have catastrophic consequences, from which the government never seem to learn. In fact they don’t even acknowledge the terrible costs that their deeply flawed policies are inflicting on citizens.

Julia Savage is a manager at Birkenhead Benefit Centre in Liverpool. In 2016, she wrote a letter (an ESA65B notification form) addressed to a GP regarding a seriously ill patient. It said:

“We have decided your patient is capable of work from and including January 10, 2016.

“This means you do not have to give your patient more medical certificates for employment and support allowance purposes unless they appeal against this decision.

“You may need to again if their condition worsens significantly, or they have a new medical condition.”

The GP subsequently repeatedly refused to provide him with new fit notes, even as his health deteriorated, and he died months later.

James Harrison – the patient – had been declared “fit for work” and the letter stated that he should not get further medical certificates. The Department for Work and Pensions contacted his doctor without telling him, and ordered him to cease providing sick certification, James died, aged 55.

He was very clearly not fit for work.

It is very worrying that the ESA65B form is a standardised response to GPs from the Department for Work and Pensions following an assessment where someone has been found fit for work.

The government as boardroom doctors: political jobsworths

The Department for Work and Pensions issued a new guidance to GPs in 2013, regarding when they should issue a Fit Note. This was updated in December 2016.

In the dogma document, doctors are warned of the dangers of “worklessness” and told they must consider “the vital role that work can play in your patient’s health”. According to the department, “the evidence is clear that patients benefit from being in some kind of regular work”.

As a matter of fact, it isn’t clear at all.

The idea that people remain ill deliberately to avoid returning to work – what Iain Duncan Smith and David Cameron termed “the sickness benefit culture” – is not only absurd, it’s very offensive. This is a government that not only disregards the professional judgements of doctors, it also disregards the judgements of ill and disabled people. However, we have learned over the last decade that political “management” of people’s medical conditions does not make people healthier or suddenly able to work.

Government policies, designed to ‘change behaviours’ of ill and disabled people have resulted in harm, distress and sometimes, in premature deaths.

Call me contrary, but whenever I am ill with my medical and not political illness, I generally trust my qualified GP or consultant to support me. I would never think of making an appointment to see the irrational likes of Esther McVey or Iain Duncan Smith for advice on lupus, or to address my health needs and treatment.

The political de-professionalisation of medicine, medical science and specialisms (consider, for example, the ghastly implications of permitting job coaches to update patient medical files), the merging of health and employment services and the recent absurd declaration that work is a clinical “health” outcome, are all carefully calculated strategies that serve as an ideological prop and add to the justification rhetoric regarding the intentional political process of dismantling publicly funded state provision, and the subsequent stealthy privatisation of Social Security and the National Health Service.

De-medicalising illness is also a part of that increasingly behaviourist-neoliberal process: “Behavioural approaches try to extinguish observed illness behaviour by withdrawal of negative reinforcements such as medication, sympathetic attention, rest, and release from duties, and to encourage healthy behaviour by positive reinforcement: ‘operant-conditioning’ using strong feedback on progress.” Gordon Waddell and Kim Burton in Concepts of rehabilitation for the management of common health problems. The Corporate Medical Group, Department for Work and Pensions, UK.

Waddell and Burton are cited frequently by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) as providing ‘scientific evidence’ that their policies are “verified” and “evidence based.” Yet the DWP have selectively funded their research, which unfortunately frames and constrains the theoretical starting point, research processes and the outcomes with a heavy ideological bias.

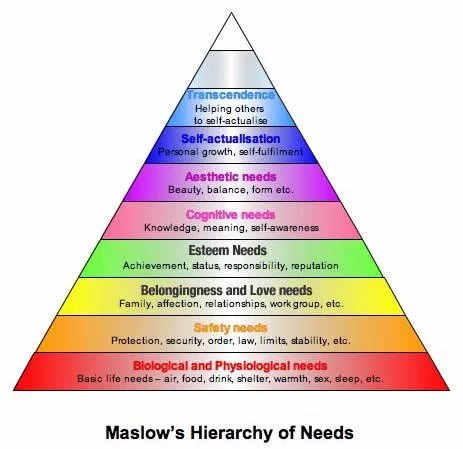

This behaviourist framing simply shifts the focus from the medical conditions that cause illness and disability to the ‘incentives’, behaviours and perceptions of patients and ultimately, to neoliberal notions of personal responsibility and self-sufficient citizenship in the dehumanising context of a night watchman, non-welfare state, absent of any notion of human rights.

Medication, rest, release from duties, sympathetic understanding – the remedies to illness – are being appallingly redefined as ‘perverse incentives’ for ill health, yet the symptoms necessarily precede the prescription of medication, the Orwellian renamed (and political rather than medical) “fit note” and exemption from work duties. Notions of ‘rehabilitation’ and medicine are being redefined as behaviour modification: here it is proposed that operant conditioning in the form of negative reinforcement – punishment – will cure’ ill health.

It’s a completely slapstick rationale, hammered into shape by a blunt instrument – political ideology. People cannot simply be ‘incentivised’ (coercion is a more appropriate term) into not being ill. Punishing people for being poor by removing their support does not ‘help’ them to stop being poor, either, despite the doublespeak and mental gymnastic pseudoscientific rubbish the government spouts.

Turning health care into a government work programme

The government dogmatically assert “The idea behind the fit note is that individuals do not always need to be fully recovered to go back to work, and in fact it can often help recovery to return to work.”

It was 2015 when I wrote a breaking article about the government’s Work and Health programme, raising concerns that the Nudge Unit team were working with the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department of Health to trial social experiments aimed at finding ways of: “preventing people from falling out of the jobs market and going onto Employment and Support Allowance (ESA).”

“These include GPs prescribing a work coach, and a health and work passport to collate employment and health information. These emerged from research with people on ESA, and are now being tested with local teams of Jobcentres, GPs and employers.”

Of course the government hadn’t announced these ‘interventions’ in the lives of ill and disabled people. I found out about it quite by chance because I happened to read Matthew Hancock’s conference speech: The Future of Public Services.

I researched a little further and found an article in Pulse – a publication for for medical professionals – which confirmed Hancock’s comment: GP practices to provide advice on job seeking in new pilot scheme. I posted my own article on the Pulse site in October 2015, raising some of my concerns.

Many of us have warned that the programme jeopardises doctor-patient confidentiality, risks alienating patients from their doctors and perverts the primary role and ethical mission of the healthcare system, which is to help people to recover from illnesses. Placing job coaches in GP surgeries makes them much less inaccessible, because it turns appointments potentially into areas of pressure and coercion. That is the very last thing someone needs when they become ill.

One worry was that the government may use the ‘intervention’ as a further opportunity for sanctioning ill and disabled people for ‘non-compliance’. People who are ill often can’t undertake work related tasks precisely because they are ill. Until recent years, this was accepted as common sense, and any expectation of sick people having to conform with such rigid welfare conditionality was quite properly regarded as both unfair and unrealistic.

I expressed concern that the introduction of job coaches in health care settings, peddling the myth that ‘work is a health outcome’ would potentially conflict with the ethics and role of a doctor. I also stated my concern about the potential that this (then) pilot had for damaging the trust between doctors and their patients.

In another article in 2016, titled Let’s keep the job centre out of GP surgeries and the DWP out of our confidential medical records, I outlined how GPs had raised their own concerns about sharing patient data with the Department for Work and Pensions – and quite properly so.

Pulse reported that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) plans to extract information from GP records, including the number of Med3s or so-called ‘fit notes’ issued by each practice and the number of patients recorded as ‘unfit’ or ‘maybe fit’ for work, in an intrusive move described by GP leaders as amounting to “state snooping.”

Part of the reason for this renewed government attack on ill and disabled people is that the Government’s flagship fit note scheme, which replaced sick notes five years ago in the hope it would see GPs sending thousands more employees back to work to reduce sickness-related absence, despite GPs having expressed doubts since before its launch, has predicably failed.

The key reason for the failure is that employers did not take responsibility for working with employees and GPs seriously, and more than half (59%) of employers said they felt unable to support employees by making all of the legally required workplace adjustments for those who had fit notes signed as “may be fit for work.” Rather than address this issue with employers, the government has decided instead to simply coerce patients back into work without essential support.

Another reason for the failure of this scheme is that most people who need time off from work are ill and genuinely cannot return to work until they have recovered. Regardless of the government’s concern for the business and state costs of sick leave, people cannot be simply ushered out of illness and into work by the state to “contribute to the economy.”

When a GP says a person is ‘unfit for work’, they generally ARE unfit for work, regardless of whether the ‘business friendly’ government likes that or not. And regardless of the politically prescribed Orwellian renaming of sick notes, which show ‘paternalist’ linguistic behaviourism in action.

In 2017, the General Medical Council (GMC) – independent regulator for doctors in the UK – wrote a response to the government’s green paper: Improving Lives: The Work, Health and Disability Green Paper consultation. The authors of the document begin by saying ” Our purpose is to protect, promote and maintain the health and safety of the public by ensuring proper standards in the practice of medicine.”

The response continues: “Where doctors are expected to play a role in initiatives such as those set out in the Green paper, our concern is to ensure that any responsibilities that might be placed on doctors would be consistent with their professional obligations and would not risk damaging patients’ trust in their doctors. While we believe that many of the Green paper proposals are promising, we are concerned that key elements appear to present a conflict with the ethical responsibilities we place on doctors. The comments below are seeking clarification in these areas.”

And: “We understand from this Green paper, and from the Department of Work and Pensions’ published FOI response, dated 22 December 2016, that the work coaches who will conduct the mandatory health and work conversation with claimants will not be health professionals. There is a risk that claimants will not get the right support in setting health and work-related goals during this mandatory conversation if the work coach does not have clinical expertise.

“It would be helpful to know whether work coaches will be expected to have access to the claimant’s healthcare team and/or health records to inform these conversations. If so, we would appreciate reassurance that there will be a process for obtaining consent from the claimant, and providing assurance to the relevant health professionals that the individual has provided consent. Given that work coaches do not require medical expertise, we have some concerns about these conversations leading claimants to agree to health-related actions in a Health and Work ‘claimant commitment’. It seems possible that agreed actions might not be clinically appropriate for that individual or not the best course of action given their health condition.

“If a claimant commitment were reviewed by the claimant’s doctor (or other healthcare professional), and the doctor concluded that there was a health risk; then would the claimant be free to withdraw from the commitment without facing a benefits penalty? If not, then this would put the doctor and patient in a very difficult position, if it appeared that the patient had been poorly advised by the work coach and was not making an informed, voluntary decision in requesting a particular treatment or care regime from their doctor.

“We note the intention is for any agreement made in the Health and Work Conversation to be seen as voluntary. However, it seems to us that since the Conversation itself is mandatory and a Claimant commitment may influence subsequent handling of an individual’s Work Capability assessment, then in practice claimants may see these agreements as mandatory.

“As a result they may feel pressured to accept advice and make commitments which may not be appropriate in their case. This would place theirdoctors in a difficult ethical position, and we are concerned to ensure that this is not the case.

The authors add: “… we make it clear in our guidance that doctors must consider the validity of a patient’s consent to treatment if it is linked with access to benefits. Doctors should be aware that patients may be put under pressure by employers, insurers, or others to accept a particular investigation or treatment (paragraph 41, Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together).

“Difficulty could arise if a doctor does not believe that a patient is freely consenting to treatment and is instead only giving consent due to financial pressure. Doctors must be satisfied that they have valid consent before providing treatment, which means they could be left with a difficult decision as to whether to refuse treatment in the knowledge that this could affect the patients benefit entitlements.”

The GMC also raise concerns about how sensitive health data is collected and shared for purposes other for patients’ direct care, without patients being informed or giving consent. The government have simply proposed to access health care data to support “any assessment for financial support” and told GPs to assume consent has been given.

Promoting the myth that work is a ‘clinical outcome’

A Department for Work and Pensions research document published back in 2011 – Routes onto Employment and Support Allowance – said that if people believed that work was good for them, they were less likely to claim or stay on disability benefits.

Of course it may be the case that people in better health work because they can, and have less need for healthcare services simply because they are relatively well, rather than because they work.

From the document: “The belief that work improves health also positively influenced work entry rates; as such, encouraging people in this belief may also play a role in promoting return to work.”

The aim of the research was to “examine the characteristics of ESA claimants and to explore their employment trajectories over a period of approximately 18 months in order to provide information about the flow of claimants onto and off ESA.”

A political decision was made that people should be “encouraged” to believe that work was “good” for their health. There is no empirical basis for the belief, and the purpose of encouraging it is simply to cut the numbers of disabled people claiming Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) by “helping” them into work.

Another government document from 2014 – Psychological Wellbeing and Work – says: “We know that being in work is good for wellbeing and that mental health problems are an increasing issue for the nation and so the Minister for Welfare Reform and the Minister for Care and Support jointly sought to expand the evidence base on common mental health problems.

“A number of Government programmes assess and support those with mental health difficulties to work, but it is internationally recognised that the evidence base for successful interventions is limited.

“The Contestable Policy Fund gives ministers alternative avenues to explore new thinking and strategies that offer cross-Government benefits. This report was commissioned through this route.”

And: “Within the time and resources available for this study the research team did not undertake extensive assessment of the quality of the evidence base (eg assessing the research design and methodology of previous studies)”

The government have gone on to declare with authoritarian flourish that they now want to reinforce their proposal that “work is a health outcome.” Last year, a report by the Mental Health Task Force and chaired by Mind’s Paul Farmer, recommended that employment should be recognised as a ‘health outcome’. I’m just wondering how people with, say, personality disorders, or psychosis are suddenly going to overcome the nature of their condition and all of a sudden successfully hold down a job for a minimum of six months.

Mind those large logical gaps…

This has raised immediate concerns regarding the extent to which people will be pushed into work they are not able or ready to do, or into bad quality, low paid and inappropriate work that is harmful to them, under the misguided notion that any work will be good for them in the long run.

It has become very evident over recent years that the labour market is not delivering an adequate income for many citizens and despite “record levels of employment”, the problem seems to be getting bigger. The government’s answer to the problem has been to extend punishment those on low pay, rather than tackle employers who pay exploitative, low wages.

The idea of the state persuading doctors and other professionals to “sing from the same [political] hymn sheet”, by promoting work outcomes in social and health care settings is more than a little Orwellian. Co-opting professionals to police the welfare system is very dangerous.

In linking receipt of welfare with health services and “state therapy,” with the single intended outcome explicitly expressed as employment, the government is purposefully conflating citizen’s widely varied needs with economic outcomes and diktats, isolating people from traditionally non-partisan networks of relatively unconditional support, such as the health service, social services, community services and mental health services.

Public services “speaking with one voice” as the government are urging, will invariably make accessing support conditional, and further isolate already marginalised social groups. Citizens’ safe spaces for genuine and objective support is shrinking as the state encroaches with strategies to micromanage those using public services. This encroachment will damage trust between people needing support and professionals who are meant to deliver essential public services, rather than simply extending government dogma, prejudices and discrimination.

State micromanagement of tenants

The GMC say in their response to the government’s proposals: “We are unclear about the evidence that might support a move to the position that ‘being in employment’ should be regarded as a ‘clinical outcome’ that healthcare professionals are expected to work towards with people of employment age seeking health-related advice and treatment. This is a highly contentious issue and indeed Dame Carol Black’s report certainly makes clear that there is limited support for this within the profession.”

I’m not unclear. There is no evidence. In an era of small state neoliberalism and ideologically driven austerity, it is an act of sheer political expediency to claim that ‘worklessness’ is the reason for the poor health outcomes that are in fact correlated with increasing inequality, poverty and lower standards of living – higher mortality; poorer general health, long-standing illness, limiting longstanding illness; poorer mental health, psychological distress, psychological/psychiatric morbidity; higher medical consultation, medication consumption and hospital admission rates.

Both social security and the National Health Service have been intentionally underfunded and run down by the Conservatives, who have planned and partially implemented a piecemeal privatisation process by stealth, to avoid a public backlash.

Unemployment (not ‘worklessness’ – that’s part of the privileged discourse of neoliberalism, which serves to marginalise the structural aspects of persistent unemployment and poverty, by transforming these into individual pathologies of benefit ‘dependency ‘and ‘worklessness’) is undoubtedly associated with poverty, because welfare provision no longer meets the most basic living costs.

However to make an inferential leap and claim that work is therefore ‘good’ for health’ is incoherent, irrational and part of an elaborate political gaslighting campaign of an authoritarian government, who simply don’t want to address growing poverty and inequality caused by their own neoliberal policies.

The direction that government policy continues to be pushed in represents a serious threat to the health, welfare, wellbeing, basic human rights, democratic inclusionand lives of patients and the political independence of health professionals.

Related

Cash for Care: nudging doctors to ration healthcare provision

Illustration by Jack Hudson

My work is unfunded and I don’t make any money from it. This is a pay as you like site. If you wish you can support me by making a one-off donation or a monthly contribution. This will help me continue to research and write independent, insightful and informative articles, and to continue to support others.