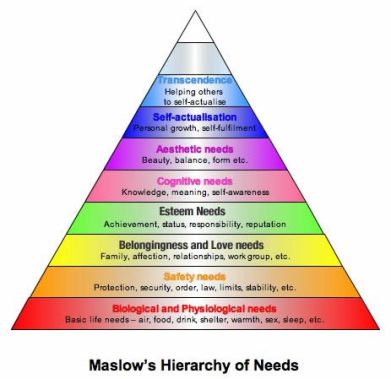

Personal Independence Payment is a non means tested benefit for people with a long-term health condition or impairment, whether physical, sensory, mental, cognitive, intellectual, or any combination of these. It is an essential financial support towards the extra costs that ill and disabled people face, to help them lead as full, active and independent lives as possible.

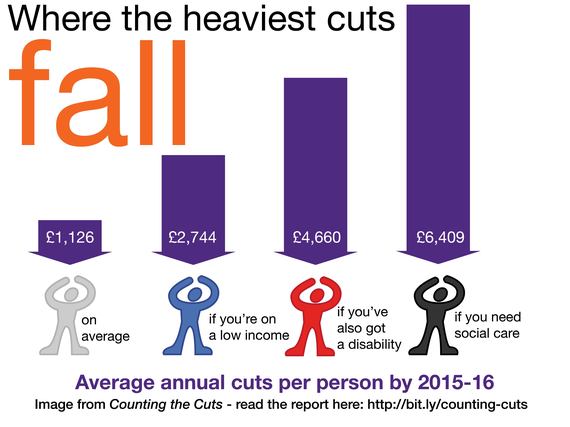

Before 2010, policies that entailed cutting lifeline support for disabled people and those with serious illnesses were unthinkable. Now, systematically dismantling social security for those citizens who need support the most has become the political norm.

Any social security policy that is implemented with the expressed aim of “targeting those most in need” and is implemented to replace a policy that is deemed “unsustainable” is invariably about cost cutting, aimed at reducing the eligibility criteria for entitlement. The government were explicit in their statement about the original policy intent behind Personal Independence Payment. However, what it is that defines those “most in need” involves ever-shrinking, constantly redefined categories, pitched at an ever-shifting political goalpost.

Disability benefits were originally designed to help sick and disabled people meet their needs, additional living costs and support people sufficiently to allow a degree of dignity and independent living. You would be mistaken in thinking, however, that Personal Independent Payment was designed for that. It seems to have been designed to provide the Treasury with ever-increasing pocket money. Or as the source of profit for private providers who constantly assess, monitor, coerce and attempt to “incentivise” those people being systematically punished and impoverished by the state to make “behaviour changes,” which entail them not being disabled or ill and taking any available employment, regardless of its suitability.

The government have already considered ways of reducing the eligibility criteria for the daily living component of Personal Independence Payment (PIP) by narrowing definitions of aids and appliances, and were kite flying further limits to eligibility for PIP last year.

Two independent tribunals have ruled that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) should expand the scope and eligibility criteria of Personal Independence Payment (PIP), which helps both in-work and out-of work disabled people fund their additional living costs.

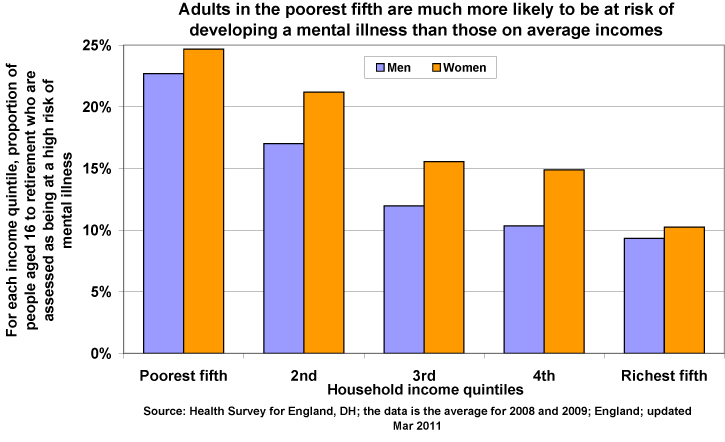

Following a court ruling in favour of disabled people last month, the government is rushing in an “urgent change” to the law to prevent many people with mental health conditions being awarded the mobility component of PIP. The court held that people with conditions such as severe anxiety can qualify for the enhanced rate of the mobility component, on the basis of problems with “planning and following a journey”, or “going out”.

The government’s new regulations will reverse the recent ruling and means that people with mental health conditions such as severe anxiety who can go outdoors, even if they need to have someone with them, are much less likely to get an award of even the standard rate of the PIP mobility component. The new regulations also make changes to the way that the descriptors relating to taking medication are interpreted, again in response to a ruling by a tribunal in favour of disabled people.

The first tribunal said more points should be available in the “mobility” element for people who suffer “overwhelming psychological distress” when travelling alone. The second tribunal recommended more points in the “daily living” element for people who need help to take medication and monitor a health condition.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) warned that it would cost £3.7bn extra by 2022 to implement the court rulings. The government have responded by formulating “emergency legislation” to stop the legal changes that the upper tribunals had ruled on from happening. From 16 March the law will be changed, without any democratic conversation with disabled people and related organisations, or debate in parliament, so that the phrase “For reasons other than psychological distress” will be added to the start of descriptors c, d and f in relation to “Planning and following journeys” on the PIP form.

It’s worth noting that the Coalition Government enshrined in law a commitment to parity of esteem for mental and physical health in the Health and Social Care Act 2012. In January 2014 it published the policy paper Closing the Gap: priorities for essential change in mental health (Department of Health, 2014), which sets out 25 priorities for change in how children and adults with mental health problems are supported and cared for. The limiting changes to PIP legislation does not reflect that commitment.

The new regulations are being rushed in without any dialogue with the Social Security Advisory Committee, too.

The government have designed regulations which would, according to Penny Mordaunt, be about “restoring the policy originally intended when the Government developed the PIP assessment”.

The original policy intent was to create an opportunity to limit eligibility for those people previously claiming Disability Living Allowance (DLA) whilst they were being reassessed for PIP, which replaced DLA. And to limit successful new claims.

Mordaunt also said in a written statement to MPs: “If not urgently addressed, the operational complexities could undermine the consistency of assessments, leading to confusion for all those using the legislation, including claimants, assessors, and the courts.

“It is because of the urgency caused by these challenges, and the implications on public expenditure, that proposals for these amendments have not been referred to the Social Security Advisory Committee before making the regulations.”

An ever-shifting, ever-shrinking goalpost

Any social security policy that is implemented with the expressed aim of “targeting those most in need” is invariably about cost cutting and reducing eligibility criteria for entitlement. The government were explicit in their statement about the original policy intent of Personal Independence Payment.

The government has already considered ways of reducing eligibility criteria for the daily living component of Personal Independence Payment by narrowing definitions of aids and appliances, last year.

Prior to the introduction of PIP, Esther McVey stated that of the initial 560,000 claimants to be reassessed by October 2015, 330,000 of these are targeted to either lose their benefit altogether or see their payments reduced.

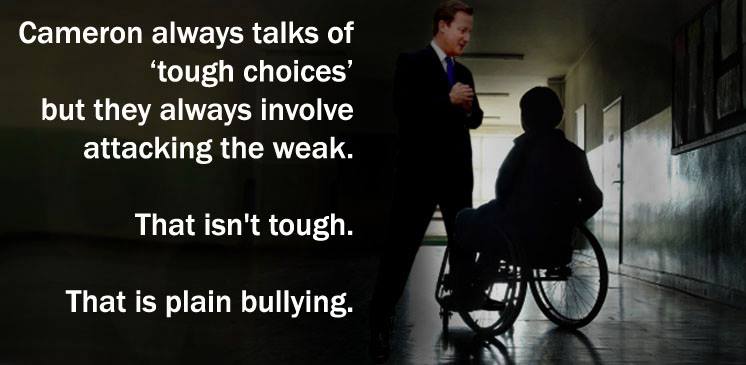

We ought to challenge a government that displays such contempt for the judicial system, and ask where the ever-reductive quest for the ever-shrinking category of “those with the greatest need” will end.

Labour’s Shadow Work and Pensions Secretary, Debbie Abrahams MP, criticised the government’s decision to overturn the tribunal rulings, she said: “Instead of listening to the court’s criticisms of PIP assessments and correcting these injustices, this government have instead decided to undermine the legal basis of the rulings”.

Abrahams added: “This is an unprecedented attempt to subvert an independent tribunal judgement by a right-wing government with contempt for judicial process.

By shifting the goal posts, the Tory Government will strip entitlements from over 160,000 disabled people, money which the courts believe is rightfully theirs. This is a step too far, even for this Tory government.”

The government seem to think that PIP is a policy that ought to benefit only the needs of a government on an ideological crusade to reduce social security away to nothing – “to target those in greatest need” – an ever-shrinking, constantly redefined and shifting category of disability.

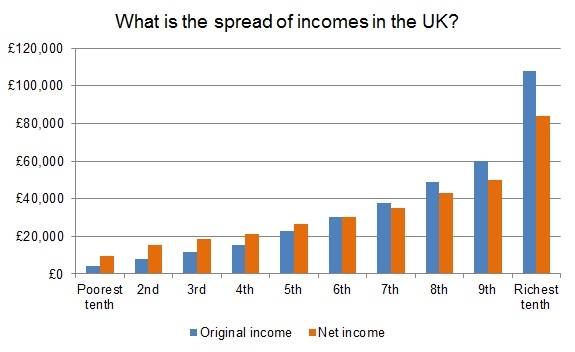

It is not a democratic government: they are unwilling to engage in a dialogue with the public or to recognise and reflect public needs: that’s an authoritarian elite taking public money and handing it out to a very wealthy minority group in the form of “incentivising” tax cuts, who then say to the public that providing lifeline support for disabled people and those with mental health/medical conditions is “unsustainable”.

Implications for the UK’s obligations regarding the UN convention on the human rights of disabled persons and the Equality Act

The new PIP changes, pushed through without any public conversation or democratic exchange with disabled people, are in breach of both the UN convention on the rights of disabled persons, and the UK Equality Act.

In the Equality Analysis PIP assessment criteria document, the government concede that: “Since PIP is a benefit for people with a disability, impairment or long-term health condition, any changes will have a direct effect on disabled people. The vast majority of people receiving PIP are likely to be covered by the definition of “disability” in the Equality Act 2010.

By definition, therefore, the UT [upper tribunal] judgment results in higher payments to disabled people, and reversing its effect will prevent that and keep payments at the level originally intended. The difference in income will clearly make a real practical difference to most affected claimants, and (depending on factors such as their other resources) is capable of affecting their ability to be independently mobile, access services etc – all matters covered by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities as set out at the start of this Analysis.”

It goes on to say in the document: “However, this does not necessarily mean that the increased payments that would result from the judgment are a fair reflection of the costs faced by those affected, or represent a fair approach as between different groups of PIP claimants.”

People with the following conditions are likely to be affected by the reversal of the upper tribunal’s ruling on those needing support to manage medication, monitor a health condition, or both:

Diabetes mellitus (category unknown), Diabetes mellitus Type 1 (insulin dependent), Diabetes mellitus Type 2 (non-insulin dependent), Diabetic neuropathy, Diabetic retinopathy, Disturbances of consciousness – Nonepileptic – Other / type not known, Drop attacks, Generalised seizures (with status epilepticus in last 12 months), Generalised seizures, (without status epilepticus in last 12 months), Narcolepsy, Non epileptic Attack disorder (pseudoseizures), Partial seizures (with status epilepticus in last 12 months), Partial seizures (without status epilepticus in last 12 months), Seizures – unclassified Dizziness – cause not specified, Stokes Adams attacks (cardiovascular syncope), Syncope – Other / type not known.

People with the following conditions are likely to be affected by the reversal of the independent tribunal’s ruling regarding PIP mobility awards, with conditions in the general category of “severe psychological distress”:

Mood disorders – Other / type not known, Psychotic disorders – Other / type not known, Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective disorder, Phobia – Social Panic disorder, Learning disability – Other / type not known, Generalized anxiety disorder, Agoraphobia, Alcohol misuse, Anxiety and depressive disorders – mixed Anxiety disorders – Other / type not known, Autism, Bipolar affective disorder (Hypomania / Mania), Cognitive disorder due to stroke, Cognitive disorders – Other / type not known, Dementia, Depressive disorder, Drug misuse, Stress reaction disorders – Other / type not known, Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Phobia – Specific Personality disorder, Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

The government’s so-called commitment to a “parity of esteem for mental health and physical health” was clearly nothing more than an empty promise – an opportunistic platitude. This is a government that says one thing and then does exactly the opposite.

It’s all part of a broader gaslighting and linguistic techniques of neutralisation strategy that passes as Conservative “justification” for their draconian deeds and bullying, discriminatory and uncivilised austerity regime, aimed disproportionately at disabled people.

Commenting on the Ministerial announcement (made yesterday, 23rd February), Rob Holland, Public Affairs Manager at Mencap and Disability Benefits Consortium Parliamentary Co-Chair said:

“We are concerned by these changes to the criteria for Personal Independence Payment (PIP). These risk further restricting access to vital support for thousands of disabled people. Last year, MPs strongly opposed restrictions to PIP and the Government promised no further cuts to disability benefits. Other changes have already had a devastating impact on thousands and in far too many cases people have had to rely on tribunals to access the support they need.

We are deeply disappointed as a coalition of over 80 organisations representing disabled people that we were not consulted about these proposals and their potential impact. The Government must ensure the views of disabled people are properly considered before they proceed with these changes.”

The full ministerial statement can be read here.

Download a copy of the new regulations here.

Related

PIP disability benefit test ‘traumatic and intrusive’

Government guidelines for PIP assessment: a political redefinition of the word ‘objective’

I don’t make any money from my work. I am disabled because of illness and have a very limited income. But you can help by making a donation to help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.

Young Bullers

Young Bullers