In the United State, regulators have approved the first “digital pill” with a tracking system. According the Financial Times, this is a pill with an inbuilt sensor, which opens up a new front in pharmaceuticals and the “internet of things”.

The tablet can be tracked inside the stomach, relaying data on whether, and when, patients have taken “vital medication”. So far, the US Food and Drug Administration has given the green light for it to be used in an antipsychotic medication with the aim that the data can be used “to help doctors and patients better manage treatment.”

Patients who agree to take the digital medication, a version of the antipsychotic drug Abilify, can sign consent forms allowing their doctors and up to four other people, including family members, to receive electronic data showing the date and time pills are ingested.

Dr. Peter Kramer, a psychiatrist and the author of Listening to Prozac, raised concerns about “packaging a medication with a tattletale.”

While ethical for “a fully competent patient who wants to lash him or herself to the mast,” he said, “‘digital drug’ sounds like a potentially coercive tool.”

Other companies are developing digital medication technologies, including another ingestible sensor and visual recognition technology capable of confirming whether a patient has placed a pill on the tongue and has swallowed it.

The newly approved pill, called Abilify MyCite, is a collaboration between Abilify’s manufacturer, Otsuka, and the Silicon Valley based Proteus Digital Health, the company that created the sensor.

The sensor, which contains copper, magnesium and silicon, generates an electrical signal when splashed by stomach fluid, “like a potato battery,” according to Andrew Thompson, Proteus’s president and chief executive.

After several minutes, the signal is detected by a Band-Aid-like patch that must be worn on the left rib cage and replaced after seven days, said Andrew Wright, Otsuka America’s vice president for digital medicine. The patch then sends the date and time of pill ingestion and the patient’s activity level via Bluetooth to a cellphone app.

Abilify is prescribed to people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and, in conjunction with an antidepressant, major depressive disorder. The symptoms of schizophrenia and related disorders can include paranoia and delusions, so you do have to wonder how widely digital Abilify will be accepted, given that it is designed to monitor behaviours and transmit signals from within a person’s body to communicate with their doctor.

Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman, chairman of psychiatry at Columbia University and New York-Presbyterian Hospital, said many psychiatrists would likely want to try digital Abilify, especially for patients who just experienced their first psychotic episode and are at risk of stopping medication after feeling better.

But he noted it has only been approved to track doses, and has not yet been shown to improve compliance with treatment regimes.

He added, “There’s an irony in it being given to people with mental disorders that can include delusions. It’s like a biomedical Big Brother.”

The FT article goes on to say: “Poor compliance with drug regimes, particularly among sufferers of chronic diseases, is a pervasive problem for pharma companies and health systems, leading to lower consumption of the industry’s products and higher costs for payers when patients’ conditions deteriorate as a result of missing treatment.”

You can see precisely where the emphasis and priorities lie in that statement. Not a word about the poor dehumanised “patients'” wellbeing and importantly, about their choice. It’s assumed that pharma industry’s products don’t have any adverse effects at all, and that taking the medication is always in the patient’s best interest. It’s assumed that medications will improve someone’s mental health. Apparently the key to good mental health is keeping costs low to tax payers while keeping the pharma industry in business, ensuring that they can keep making profits.

Andrew Thompson, Proteus chief executive, said the technology would allow people with serious mental illness “to engage with their care team about their treatment plan in a new way”. Patients will be able to use a mobile phone to track and “manage” their medication. Worryingly, he is already in talks with other major pharma companies about using the technology in treatments for various chronic conditions.

The tablets contain a sensor, so that when they are swallowed, a signal is sent to a patch worn on the patient’s body, which in turn connects to an app on their phones, showing that they have taken their dose. The doctor who has prescribed the medicine will automatically be sent the data and patients can also choose to nominate family and care team members to receive it.

The wearable patch will also be used to track how much patients are moving around — considered a key indicator of overall health — and allows them to self-report their mood and sleep quality via the app.

There are some problems with the assumptions behind the development of digital pill, and its proposed use. Firstly, it’s a myth that people with mental health conditions are not very good at taking their medication. Studies have shown that “compliance” with a medication regime is no worse in people with mental health conditions like schizophrenia than it is in long-term physical ailments such as asthma or high blood pressure. In fact demographic factors such as whether a person is single or in a relationship are more likely to play a role in medication compliance.

It is also a taken for granted assumption that pharmaceutical solutions are the best guarantee of positive outcomes for people with mental health conditions. Before concentrating on specific medication issues it is important to remember that medication is not the sole focus of a mental health intervention. This is because the causes of mental illness are complex and various, and quite often do not arise solely from “within” individuals, rather, it often arises because of interactions between environmental factors, circumstances, and individual predispositions and vulnerabilities (including both psychological and biological). Some psychiatrists have stated that mental illness – in all its forms – is intrinsically social.

We know, for example, that discrimination plays a part in explaining why certain groups in our society are more likely to experience poor mental health compared to others. Direct experiences of prejudice and harassment impact negatively on mental wellbeing, while indirect factors such as deprivation and social exclusion also contribute to poor mental health. Studies have highlighted the role that prejudice, stigma and discrimination can play in poor mental health.

It is only by fully acknowledging and understanding the external risk factors for poor mental health that we can develop our understanding of protective factors for good mental health at the individual, community and societal level.

Sometimes causes are confused with effects

Despite controversies in psychiatry regarding the very complex aetiology of mental illness, including the role of sociological practices, political practices and economic conditions, it is widely held that mental illness arises “within” the individual and has a purely neurobiological origin. Yet there is no conclusive evidence to demonstrate that major mental illnesses are “proven biological diseases of the brain” and that emotional distress results from “chemical imbalances.”

One attempt to explain a physical cause of schizophrenia is the dopamine hypothesis. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter. It is one of the chemicals in the brain which causes neurons to fire. The original dopamine hypothesis stated that people with schizophrenia suffered from an excessive amount of dopamine. This causes the neurons that use dopamine to fire too often and transmit too many “messages”. High dopamine activity leads to acute episodes, and positive symptoms which include delusions, hallucinations and “confused thinking.”

Evidence for this hypothesis comes from that fact that amphetamines increase the amounts of dopamine. Large doses of amphetamine given to people with no history of psychological disorders produce behavior which is very similar to paranoid schizophrenia. Small doses given to people already suffering from schizophrenia tend to worsen their symptoms.

However, the problem with this hypothesis is that we don’t know if the raised dopamine levels are the cause of the schizophrenia, or if the raised dopamine level is the result of schizophrenia. It is not clear which comes first.

One of the biggest criticisms of the dopamine hypothesis came when Farde et al found no difference between levels of dopamine in people with schizophrenia compared with “healthy” individuals in 1990.

Another problem is that schizophrenia is something of an umbrella term that encompasses a wide array of symptoms, and can be reached by multiple routes that may, nevertheless, impact the same biological pathways. However, there is emerging evidence that different routes to experiences currently deemed indicative of schizophrenia may need different treatments.

For example, preliminary evidence suggests that people with a history of childhood trauma who are diagnosed with schizophrenia are less likely to be helped by antipsychotic drugs. However, more research into this is needed. It has also been suggested that some cases of schizophrenia are actually a form of autoimmune encephalitis, which means that the most effective treatment may be immunotherapy and corticosteroids. People with autoimmune illness such as lupus are also at an increased risk of developing autoimmune mediated psychosis.

Some interventions, such as the family-therapy based dialogue approach, show some promise for many people with schizophrenia diagnoses. Both general interventions and specific ones, tailored to someone’s personal route to the experiences associated with schizophrenia, may be needed. It’s therefore crucial that psychiatrists ask people about all the potentially relevant circumstances and routes.

For example, suffering childhood adversity, using cannabis and having childhood viral infections of the central nervous system all increase the odds of someone being diagnosed with a psychotic disorder (such as schizophrenia) by at least two – to threefold.

Although the exact causes of most mental illnesses are not known, it is becoming clear through extensive research that many conditions are caused by a complex combination of biological, psychological, social, cultural, political, economic and environmental factors. It’s widely recognised that poverty, social isolation, being unemployed or highly stressed in work can all have an effect on an individual’s mental health.

Adults in the poorest fifth of the population are much more at risk of developing a mental illness as those on average incomes: around 24% compared with 14%. Those who have an existing mental illness are significantly more likely to be living in poverty, also.

Poverty can therefore be both a causal factor and a consequence of mental ill-health. Mental health is shaped by the wide-ranging characteristics (including inequalities) of the social, economic, political and physical environments in which people live.

Successfully supporting the mental health and wellbeing of people living in poverty, and reducing the number of people with mental health problems experiencing poverty, requires an engagement with this complexity. Simply medicating a person is neither sufficient nor appropriate. Nor is it ethical. Pharmaceutical companies tend to promote the assumption that mental illness is entirely biomedical. The relationship between economics and health is complex and politically fraught. But it is too important to ignore.

Psychiatric diagnosis tends to reify the complexity of people’s problems. However, in the UK, the political (mis)use of behaviourism has also resulted in the reification of social and economic problems. The government here extend the view that unemployment is evidence of both personal failure and psychological deficit. The use of crude behaviourist psychology in the delivery of social security denies the individuals’ experience of the effects of social and economic inequalities, and has been used to authorise the extension of the state and to justify state-contracted surveillance to individuals’ psychological characteristics.

In a “business friendly” environoment, with a distinctly authoritarian government, I can’t help but wonder how long will it be before we see the increasingy intrusive Conservative state locking up or drugging patients whose diseases are defined not by organic dysfunction but by politically defined “socially unacceptable behaviours”.

I’m a critic of state entanglement with psychiatry AND psychology. For people with mental health problems in the UK, policies are being formulated to act upon them as if they are objects, rather than autonomous human subjects. Such a dehumanising approach has contributed significantly to a wider process of social outgrouping, increasing stigmatisation and ultimately, to further socioeconomic and mental health inequalities. Most government policies aimed at ill and disabled people more generally are about cutting costs and removing lifeline support. This has been increasingly justified by a narrative that focuses on problematising sick role behaviours, rather than on the real impacts of illness and the additional needs that being chronically ill invariably generates.

Earlier this year, George Freeman, Conservative MP for Norfolk and chair of the Prime Minister’s Policy Board, defended the government’s decision to subvert the judicial system, by disregarding the rulings of two independent tribunals concerning Personal Independence Payment (PIP) for disabled people. The government ushered in an “emergency” legislation to reverse the legal decisions in order to cut cost. In an interview on Pienaar’s Politics, on BBC 5 Live, Freeman said:

“These tweaks [new regulations to cut PIP eligibility] are actually about rolling back some bizarre decisions by tribunals that now mean benefits are being given to people who are taking pills at home, who suffer from anxiety”.

He claimed that the “bizarre” upper tribunal rulings meant that“claimants with psychological problems, who are unable to travel without help, should be treated in a similar way to those who are blind.”

He said: “We want to make sure we get the money to the really disabled people who need it.”

He added that both he and the Prime Minister “totally” understood anxiety, and went on to say: “We’ve set out in the mental health strategy how seriously we take it.”

He said: “Personal Independence Payments reforms were needed to roll back the bizarre decisions of tribunals.”

Freeman’s controversial comments about people with anxiety “at home taking pills” implies that those with mental health problems are somehow faking their disability. He trivialises the often wide-ranging disabling consequences of mental ill health, and clearly implies that he regards mental illnesses as somehow not “real” disabilities.

His comments contradict the government’s pledge to ensure that mental health and physical health are given a parity of esteem, just months after the Prime Minister pledged to take action to tackle the stigma around mental health problems.

Yet people with the following mental health conditions are likely to be affected by the reversal of the Independent Tribunal’s ruling on PIP mobility awards – those in particular who suffer “overwhelming psychological distress” when travelling alone:

Mood disorders – Other / type not known, Psychotic disorders – Other / type not known, Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective disorder, Phobia – Social Panic disorder, Learning disability – Other / type not known, Generalized anxiety disorder, Agoraphobia, Alcohol misuse, Anxiety and depressive disorders – mixed Anxiety disorders – Other / type not known, Autism, Bipolar affective disorder (Hypomania / Mania), Cognitive disorder due to stroke, Cognitive disorders – Other / type not known, Dementia, Depressive disorder, Drug misuse, Stress reaction disorders – Other / type not known, Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Phobia – Specific Personality disorder, Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

Freeman’s comments signposts the Conservative’s “deserving” and “undeserving” narrative, implying that some disabled people are malingering. However, disabled people do not “cheat” the social security system: the system has been redesigned by the government to cheat disabled people.

When people are attacked, oppressed and controlled psychologically by a so-called democratic government that embeds punishment at the heart of public policies to target the poorest citizens, it’s hardly surprising they become increasingly anxious, depressed and mentally unwell.

An era of technocratic solutions for social problems

Some psychiatrists see a strengthening of psychiatry’s identity as essentially “applied neuroscience”. Although not discounting the importance of the neurological sciences and psychopharmacology, they have argued that psychiatry needs to move beyond the dominance of the current dominant technological paradigm. Such critical practitioners say that psychiatry ought to primarily involve engagement with the non-technical dimensions of their work such as relationships, meanings and values. Psychiatry has operated from within a technological paradigm that, although not ignoring these aspects of work, has kept them as secondary concerns.

Psychiatry sits within a predominantly biomedical idiom. This means that problems with feelings, thoughts, behaviours and relationships can be fully grasped with the same sort of scientific tools that we use to investigate physical problems with our kidneys, blood cells, lungs, and so on.

While psychiatry has generally focused a lot of attention on neuroscience, neuroscientists themselves have become more cautious about the value of reductionist and deterministic approaches to understanding the nature of human thought, emotion and behaviour.

The dominance of this paradigm can be seen in the importance attached to classification systems, causal models of understanding mental distress and the framing of psychiatric care as a series of discrete interventions that can be analysed and measured independent of context.

More recently, models of cognitive psychology, based on “information processing”, have been developed that work within the technological idiom. Psychiatry stubbornly operates within a positivist tradition, and subscribes to the following assumptions: mental health problems arise from faulty mechanisms or processes involving abnormal physiological or psychological events occurring within the individual, these processes can be modelled in causal terms.

These processes are regarded as not being context dependent. They reside “within” the individual. Technological interventions are instrumental and can be designed and studied independently of experiences, subjective states, relationships, and values. However, in 2013, psychiatrist Allen Frances said that “psychiatric diagnosis still relies exclusively on fallible subjective judgments rather than objective biological tests”.

Many people within the growing service user movement seek to reframe experiences of mental illness, distress and alienation by framing them as human experiences, rather than biomedical events, simplistic causal relationships and “scientific” challenges. In a study of users’ views of psychiatric services, Rogers et al found that many service users did not really value the “technical” expertise of professionals. Instead, they were much more concerned with the subjective experience and human elements of their encounters such as being listened to, taken seriously, and treated with dignity, kindness and respect.

The Extraction of the Stone of Madness by Hieronymus Bosch, from around 1494.

In his work, History of Madness, Michel Foucault says “Bosch’s famous doctor is far more insane than the patient he is attempting to cure, and his false knowledge does nothing more than reveal the worst excesses of a madness immediately apparent to all but himself.”

I have to say I have never seen a person by looking at a brain.

It’s not all “in here”, it’s “out there”: the problem with locating mental illness “within” the individual

To paraphrase R.D Laing, “insanity”, mental illness and psychological distress may be seen as a perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world. Laing examined the nature of human experience from a phenomenological perspective, as well as exploring the possibilities for psychotherapy in an existentially distorted world. He challenges the whole idea of “normality” in society.

It simply isn’t effective or appropriate to treat distress arising because of, say, socioeconomic problems or difficult relationships with psychotropic drugs alone, administered to people experiencing the consequences of political decision-making, the adverse consequences of socioeconomic organisation, exclusion, stigma, abuse or damaging parenting practices.

Coping with past or current traumatic experiences such as abuse, bereavement or divorce will also strongly influence an individual’s mental and emotional state which can in turn have an influence on their wider mental health. Psychological interventions are therefore a crucial and integral part of effective treatment for mental illnesses.

However, in the UK, the current political-psychological model also locates social problems “within” the individual. The government plan to merge health and employment services. In a move that is both unethical and likely to present significant risk of harm to many patients, health professionals are being tasked to deliver benefit cuts for the Department for Work an Pensions. This involves measures to support the imposition of work cures, including setting employment as a clinical outcome and allowing medically unqualified job coaches to directly update a patient’s medical record.

The Conservatives have proposed more than once the mandatory treatment for people with long term conditions (which was first flagged up in the Conservative Party Manifesto) and this is currently under review, including whether benefit entitlements should be linked to “accepting appropriate treatments or support/taking reasonable steps towards “rehabilitation”. The work, health and disability green paper and consultation suggests that people with the most severe illnesses in the support group may also be subjected to welfare conditionality and sanctions.

Such a move has extremely serious implications. It would be extremely unethical and makes the issue of consent to medical treatment very problematic if it is linked to the loss of lifeline support or the fear of loss of benefits. However this is clearly the direction that government policy is moving in and represents a serious threat to the human rights of patients and the independence of health professionals.

The digital pill in an age of surveillance has potential implications for civil liberties

For people with severe and enduring mental health problems, it is crucial that their context is also considered, and it’s important that people are provided with support with their living circumstances, and taking into account their wider social conditions, also.

Furthermore, there is the important issue of drug tolerability to consider. Antipsychotic drugs are also associated with adverse effects that can lead to poor medication adherence, stigma, distress and impaired quality of life. For example, the stiffness, slowness of movement and tremor of antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism (See Dursun et al, 2004) can make it difficult for a patient to write, fasten buttons and tie shoelaces. Some antipsychotic medications can affect facial expressions, which flatten nonverbal communication and may impact on ordinary social interactions, potentially leading to stigma and further isolation.

Side effect or symptom?

The impact of drug side-effects on patients has not been sufficiently studied. Researchers have stressed the importance of the patient’s subjective experience, in which adverse effects have a role, and are considered and included in the assessment of drugs, though this doesn’t always happen. Although adverse effects are an important outcome, with many antipsychotics, they account for less treatment discontinuation than lack of efficacy; this finding has been noted in naturalistic studies and in Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs).

Both older and newer antipsychotic drugs can cause:

- Uncontrollable movements, such as tics, tremors, or muscle spasms, blank facial expression and abnormal gait (risk is higher with first-generation antipsychotics)

- Weight gain (risk is higher with second-generation antipsychotics)

- Photosensitivity – increased sensitivity to sunlight

- Anxiety

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Restlessness

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Blurred vision

- Low blood pressure

- Seizures

- Low white blood cell count

- Sexual dysfunction in both men and women

- Menstruation problems in women and feminising effects such as abnormal breast growth and lactation in men. These latter problems are caused by the effect that the newer drugs have on a hormone in the blood called prolactin

- Osteoporosis

- Some neuroleptic drugs have withdrawal effects which can be very unpleasant

In addition some side effects of the newer antipsychotics may be confused with the symptoms of schizophrenia, such as apathy and withdrawal.

Antipsychotics can also cause bad interactions with other medications.

Bioethic considerations

One of the serious bioethic considerations is whether the digital medicine could be used coercively, on people against their will or as part of probation, healthcare or welfare conditions, for example.

Otsuka has said: “We intend that this system only be used with patient consent.”

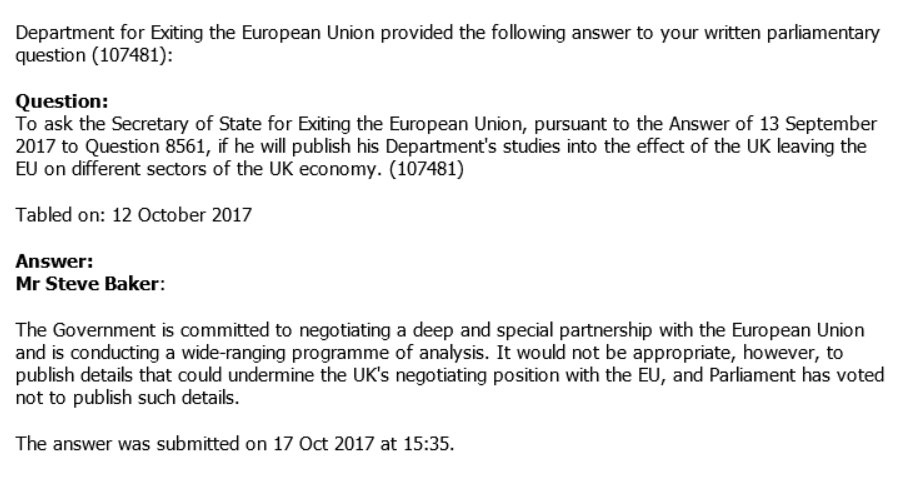

However, here in the UK, the government have been kite-flying the idea of social security support being made conditional to imposed “health” regimes for a while.

The Conservatives have already made proposals to strip obese or those who are ill because of substance misuse of their welfare benefits if they refuse treatment. This violates medical ethics. The president of the British Psychological Society responded, at the time, Professor Jamie Hacker Hughes, said people should not be coerced into accepting psychological treatment and, if they were, evidence shows that it simply would not work.

He went on to say: “There is a major issue around consent, because as psychologists we offer interventions but everybody has got a right to accept or refuse treatment. So we have got a big concern about coercion.”

Hacker Hughes lent his voice to a chorus of criticism following the announcement of an official review to consider how best to get people suffering from obesity, drug addiction or alcoholism back into work.

The government consultation paper, launched in 2015, that raised concerns acknowleged that strong ethical issues were at stake, but at the same time also questioned whether people should continue to receive benefits if they refused state provided treatment.

The government regard work as a health outcome, and believe that welfare creates “perverse incentives” that prevent people from finding employment. However, international research and evidence demonstrates that this is untrue, and that generous welfare states tend to be correlated with a stronger work ethic.

Hacker Hughes said claimants with obesity and addiction problems often faced complex mental health issues. But he warned the government against using sanctions to force people to accept interventions.

“It’s a problem firstly because we don’t believe people should be coerced into accepting any treatment, and secondly there is a problem because the evidence shows that if you are trying to change people’s behaviour, coercion doesn’t work,” he said.

There is a well-documented link between being out of work and psychological problems, but Hacker Hughes pointed out that the government’s plan risked “confusing the symptoms with the cause.”

Paul Atkinson, a London-based psychotherapist and member of the Alliance for Counselling and Psychotherapy, called the government’s proposals an outrage. He said: “It’s the same psychology from the government of punishing rather than working with people. Under a regime like welfare and jobcentres at the moment it is going to be felt as abuse, punitive and moralistic.”

Yes, and that’s because it is.

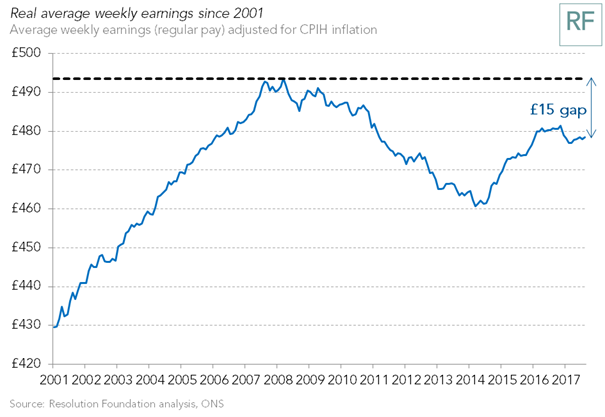

The government introduced “ordeals” into the welfare system to deter people from claiming the social security that most have paid for via national insurance and tax contributions, in order to “deter” what they see as “welfare dependency”. Yet labor market deregulation, anti-union legislation and other political decisions have also driven down wages, leaving many in work in poverty, also. The government’s “solution” to in-work poverty was to introduce further conditionality, in the form of extremely punitive financial sanctions for people who need to claim in-work welfare support, to “ensure they progress in work”. It is assumed that the problem of low pay resides “within the individual” rather than being the consequence of structural and labor market conditions, the profit incentive, “business friendly” political decision-making and board room choices. Ultimately, it’s down to the unequal distribution of power.

A gaslighting state: punitive psychopolicy interventions

No-one seems to be concerned with monitoring the impact of the government’s “behavioural change” agenda. Strict behavioural requirements and punishments in the form of sanctions are an integral part of the Conservative ideological pseudo-moralisation of welfare, and their “reforms” aimed at making claiming benefits much less attractive than taking a low paid, insecure, exploitative job.

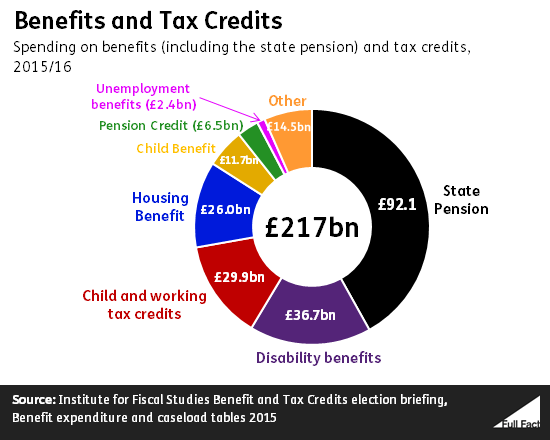

Welfare has been redefined: it is preoccupied with assumptions about and modification of the behaviour and character of recipients rather than with the alleviation of poverty and ensuring economic and social wellbeing. Furthermore, the political stigmatisation of people needing benefits is designed purposefully to displace public sympathy for the poor, and to generate moral outrage, which is then used to further justify the steady dismantling of the welfare state. (See Stigmatising unemployment: the government has redefined it as a psychological disorder.)

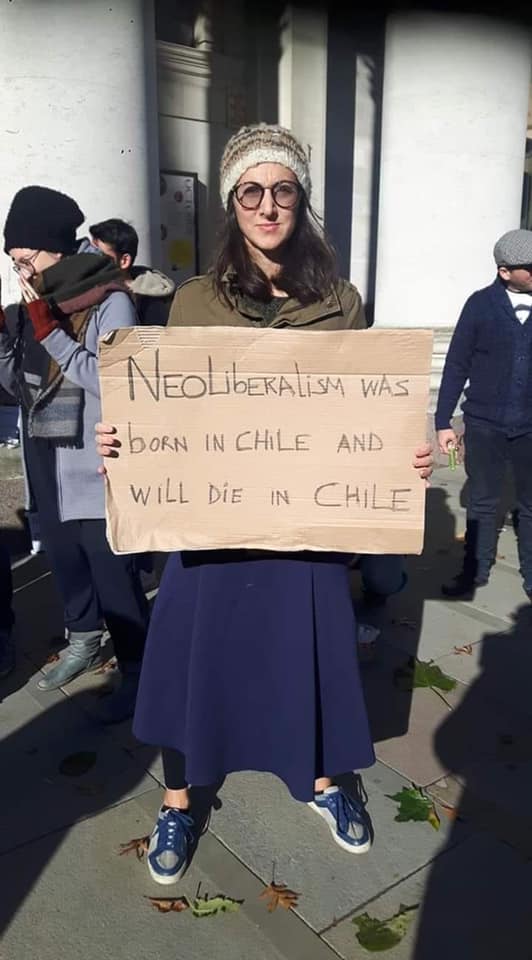

However, the problems of austerity and the economy were not caused by people claiming welfare, or by any other powerless, scapegoated, marginalised group for that matter, such as migrants. The problems have arisen because of social conservatism and neoliberalism. The victims of the government’s policies and decision-making are being portrayed as miscreants – as perpetrators of the social problems caused by the government’s decisions, rather than as the casualities.

Under the government’s plans, therapists from the NHS’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme are to support jobcentre staff to assess and treat claimants, who may be referred to online cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) courses.

Again, we really must question the ethics of linking receipt of welfare with “state therapy,” which, upon closer scrutiny, is not therapy at all. Linked to such a narrow outcome – getting a job – this is nothing more than a blunt behaviour modification programme. The fact that the Conservatives plan to make receipt of benefits contingent on participation in “treatment” worryingly takes away the fundamental right of consent.

Not only is the government trespassing on an intimate, existential level; it is tampering with our perceptions and experiences, damaging and isolating the poorest, burdening them with the blame for the consequences of their own policies whilst editing out state responsibilities towards citizens. (See the The power of positive thinking is really political gaslighting, and IAPT is value-laden, non-prefigurative, non-dialogic, antidemocratic and reflects a political agenda.)

It’s very important that we don’t overlook the importance of context regarding psychological distress. The idea that mental “illness” arises strictly “within” the individual, therefore, requiring medicine as treatment, as opposed to, say, different socioeconomic policies, is a controversial one. People’s mental health is, after all, at least influenced by the social, political, cultural and economic spaces that they occupy.

The current government has a 7 year history of decontextualing structural inequality and poverty, using narratives that “relocate” the causes and effects of an unequal distribution of power and wealth. Such narratives are about coercing the responsibility, internalisation and containment of social problems within some targeted individuals in some marginalised social groups. This process always involves projection, stigmatising, outgrouping and scapegoating.

Earlier this year, the UK Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP) said that government policies – in particular, the Conservatives’ draconian “reforms” of social security payments and austerity regime – were to blame for a steep rise in the rates of severe anxiety and depression among unemployed people, as benefit cuts and sanctions, together with an extremely punitive and coercive welfare conditionality regime, “are having a toxic impact on mental health”.

It’s hardly ethical, appropriate or effective to impose a medical treatment on people who are suffering because of policies that bring about financial and psychological insecurity, hardships and harms.

We have witnessed an ongoing attempt by the Conservatives to “rewrite the welfare contract” for disabled people, which has become a key site of controversy within UK welfare reform, and fierce debates about the circumstances in which the use of conditionality may, or may not, be ethically justified. And denial from the government that their welfare policy is causing some of our most vulnerable citizens harm, hardship and distress.

Wilkinson and Pickett’s key finding in their work, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better is that it is the inequality itself, and not the overall wealth of a society that is the key factor in creating various pathologies. The authors show that for each of eleven different health and social problems: physical health, mental health, drug abuse, education, imprisonment, obesity, social mobility, trust and community life, violence, teenage pregnancies, and child wellbeing, outcomes are significantly worse in more unequal rich countries. The evidence also shows that poorer places with more equality have better overall social outcomes than wealthy ones marked by gross inequality. (See also The still face paradigm, the just world fallacy, inequality and the decline of empathy, for further discussion about how neoliberaism itself creates profound psychological trauma, and builds social “empathy walls”).

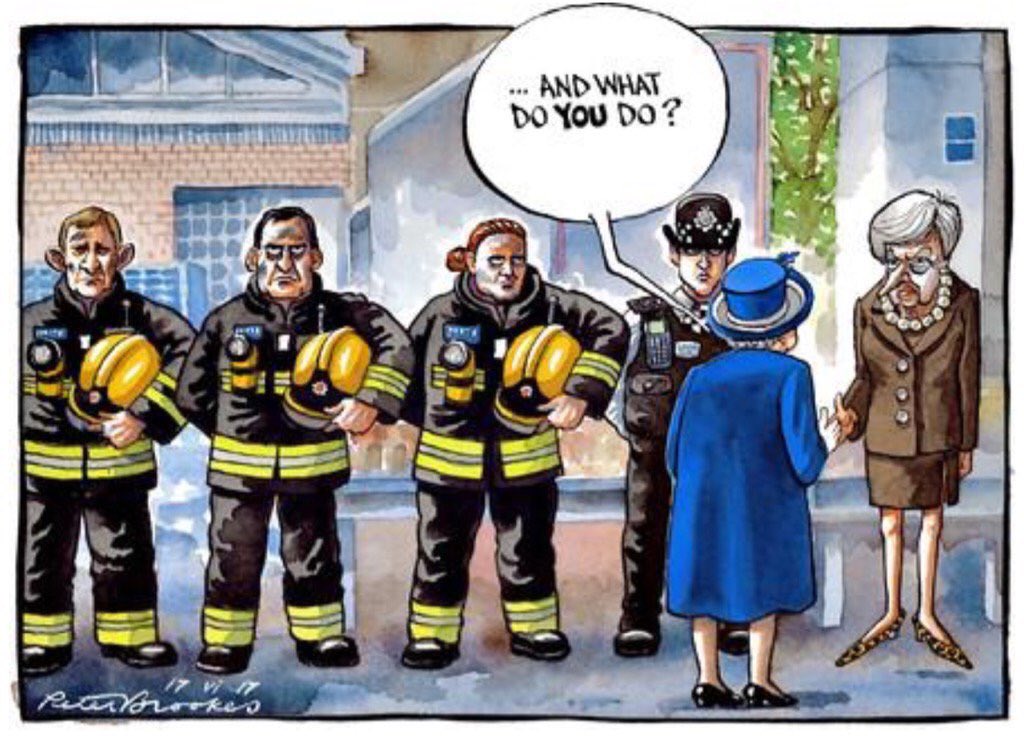

Theresa May has pledged new initiatives to end “stigma” around mental health and encourage schools and employers to provide mental health support. Despite government assurances mental health services would receive equal treatment to physical health, 40% of NHS trusts saw cuts to mental health services across 2015-2016.

But in the absence of genuine funding commitments, the Prime Minister has faced charges of hypocrisy from mental campaigners, for not doing anywhere near enough to address the root causes of problems faced by disabled and mentally ill people.

At one point in 2014, there were no mental health beds available for adults in the whole of England, while an NSPCC survey published in October 2015 found that more than a fifth of children referred to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) in England were refused access to support.

There have recently been a number of high-profile cases reported more than once in the media across the UK when the necessary kind of hospital bed could not be found for mental health patients in England. The NHS Confederation’s Mental Health Network – the representative body for NHS-funded mental health service providers – also heard evidence from its members last year that “there are occasions when there are no routine acute mental health assessment beds available across the country.”

Importantly, Psychologists Against Austerity have said: “Addressing mental health is not just about ensuring more ‘treatment’ is available and stigma is reduced, although they are important. It is fundamentally also about the evidence that ideological economic policies, like the continued austerity programme, have hit the most vulnerable citizens the hardest and have been toxic for mental health.”

The government’s “employment and support programme” for sick and disabled people coincided with at least 590 “additional” suicides, 279,000 cases of mental illness and 725,000 more prescriptions for antidepressants – and one mental health charity found that at least 21 per cent of their patients had experienced suicidal thoughts due to the stress of the draconian Work Capability Assessments.

It’s crucially important that a positive therapeutic alliance based on trust is developed between doctors and patients. Specific problems with the therapeutic alliance include doctors failing to acknowledge patients’ concerns, an example of which is the failure to respond to patients who talk about their auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia (McCabe et al, 2002). Furthermore, doctors appear not to appreciate the degree of distress caused by certain antipsychotic side-effects (Day et al, 1998). There is, therefore a fundamental need for doctors to listen more effectively to patients and elicit their particular concerns about their illness and its treatments. In fact Poor doctor-patient relationships have been cited by recent research as a key factor that influences a patient’s attitude towards treatment.

Critics of psychiatry commonly express a concern that the path of diagnosis and treatment is primarily shaped by profit prerogatives, echoing a common criticism of general medical practice, particularly in the United States, and increasingly, in the UK, where many of the largest psychopharmaceutical producers are based.

It’s an inbuilt “cognitive bias”.

This critique is not meant to imply that physiological factors in mental illnesss can or should be ignored. However, as I’ve pointed out, the biomedical model avoids the personal, social, cultural, political and economic dimensions of mental illness, in the same way that the political behaviourist (behavioural economics, used in public policy) model does.

One concern is that both the behaviourist and biomedical model protects those formulating provision and care from the pain experienced by those needing support. The temptation to retreat into objectification of those identified as mentally ill may also be a factor in a state cost cutting exercise.

The UK government has already demonstrated a worrying overreliance on individualistic approaches to socioeconomic problems that prioritise citizen responsibility and “self help”. The behavioural turn has been powerfully influenced by libertarian paternalism – itself a political doctirne, despite its claims to “value-neutrality”.

The Conservatives’ neoliberal policies increasingly embed behaviour modification techniques that aim to quantifiably change the perceptions and behaviours of citizens, aligning them with narrow neoliberal outcomes through rewards or “consequences.” Rewards, such as tax cuts, are aimed at the wealthiest, whereas the most vulnerable citizens who are the poorest are simply presented with imposed cuts to their lifeline support as an “incentive” to not be poor. Taking money from the poorest is apparently “for their own good”, according to the government, as it reduces “dependency”.

“Dependency” and “need” have somehow become conflated, the government have resisted urges to acknowledge that some citizens have more needs than others for a wide array of reasons, including their mental health status.

Defining human agency and rationality in terms of economic outcomes is extremely problematic. And dehumanising. Despite the alleged value-neutrality of behavioural economic theory and CBT, both have become invariably biased towards the status quo rather than progressive change and social justice.

Behavoural economics theory has permited policy-makers to indulge ideological impulses whilst presenting them as “objective science.” From a libertarian paternalist perspective, the problems of neoliberalism don’t lie in the market, or in growing inequality and poverty: neoliberalism isn’t flawed, nor are governments – we are. Governments and behavioural economists don’t make mistakes – only citizens do. No-one is nudging the nudgers.

It’s assumed that their decision-making is infallible and they have no whopping cognitive biases of their own. One assumption that has become embedded in the poliical narrative is that an adequate level of social security to meet people’s basic survival needs is somehow mutually exclusive from encouraging people to find a suitable job.

In the current political context, it’s easy to see how the medicalisation of political, economic, cultural and social problems may be politically misused, especially by an authoritarian government, and in an ideological era that extolls the virtues of a “small state” and austerity, to exempt the state completely from its fundamental responsibility towards the prosperity, health and wellbeing of citizens.

Neoliberalism

I don’t make any money from my work. But you can support me by making a donation and help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.