The goverment’s archaic positivist approach to social research shows that they need a team of sociologists and social psychologists, rather than the group of “libertarian paternalists” – behavioural economists – at the heart of the cabinet office, who simply nudge the public to behave how they deem appropriate, according to a rigid, deterministic, reductive neoliberal agenda and traditional, class-contingent Conservative prejudices.

Glossary

Epistemology – The study or theory of the nature and grounds of knowledge, especially with reference to its limits, reliability and validity. It’s invariably linked with how a researcher perceives our relationship with the world and what “social reality” is (ontology), and how we ought to investigate that world (methodology). For example, in sociology, some theorists held that social structures largely determine our behaviour, and so behaviour is predictable and objectively measurable, others emphasise human agency, and believe that we shape our own social reality to a degree, and that it’s mutually and meaningfully negotiated and unfixed. Therefore, detail of how we make sense of the world and navigate it is important.

Interpretivism – In sociology, interpretivists assert that the social world is fundamentally unlike the natural world insofar as the social world is meaningful in a way that the natural world is not. As such, social phenomena cannot be studied in the same way as natural phenomena. Interpretivism is concerned with generating explanations and extending understanding rather than simply describing and measuring social phenomena, and establishing basic cause and effect relationships.

Libertarian paternalism – The idea that it is both possible and legitimate for governments, public and private institutions to affect and change the behaviours of citizens whilst also [controversially] “respecting freedom of choice.”

Methodology – A system of methods used in a particular area of study or activity to collect data. In the social sciences there has been disagreement as to whether validity or reliability ought to take priority, which reflected ontological and epistemological differences amongst researchers, with positivism, broadly speaking, being historically linked with structural theories of society – Emile Durkheim’s structural-functionalism, for example – and quantitative methods, usually involving response-limiting surveys, closed-ended questionaires and statistical data collection, whereas interpretive perspectives, such as symbolic interactionism, phenomenology and ethnomethodology, tend to be associated with qualitative methods, favoring open-ended questionaires, interviews and participant observation.

The dichotomy between quantitative and qualitative methodological approaches, theoretical structuralism (macro-level perspectives) and interpretivism (micro-level perspectives) is not nearly so clear as it once was, however, with many sociologists recognising the value of both means of data collection and employing methodological triangulation, reflecting a commitment to methodological and epistemological pluralism. Qualitative methods tend to be more inclusive, lending participants a dialogic, democratic voice regarding their experiences.

Ontology – A branch of metaphysics concerned with the nature of reality and being. It’s important because each perspective within the social sciences is founded on a distinct ontological view.

Positivism – In sociology particularly, the view that society, like the physical world, operates according to general laws, and that all authentic knowledge is that which is verified. However, the verification principle is itself unverifiable.

Positivism tends to present superficial and descriptive rather than in-depth and explanatory accounts of social phenomena. In psychology, behaviourism has been the doctrine most closely associated with positivism. Behaviour from this perspective can be described and explained without the need to make ultimate reference to mental events or to internal psychological processes. Psychology is, according to behaviourists, the “science” of behaviour, and not the mind.

Critical realism – Whilst positivists and empiricists more generally, locate causal relationships at the level of observable surface events, critical realists locate them at the level of deeper, underlying generative mechanisms. For example, in science, gravity is an underlying mechanism that is not directly observable, but it does generate observable effects. In sociology, on a basic level, Marx’s determining base (which determines superstructure) may be regarded as a generative mechanism which gives rise to emergent and observable properties.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) – RCT is a positivist research model in which people are randomly assigned to an intervention or a control (a group with no intervention) and this allows comparisons to be made. Widely accepted as the “gold standard” for clinical trials, the foundation for evidence-based medicine, RCTs are used to establish causal relationships. These kinds of trials usually have very strict ethical safeguards to ensure the fair and ethical treatment of all participants, and these safeguards are especially essential in government trials, given the obvious power imbalances and potential for abuse. A basic principle expressed in the Nuremberg Code is the respect due to persons and the value of a person’s autonomy, for example.

In the UK, the Behavioural Insight Team is testing paternalist ideas for conducting public policy by running experiments in which many thousands of participants receive various “treatments” at random. Whilst medical researchers generally observe strict ethical codes of practice, in place to protect subjects, the new behavioural economists are much less transparent in conducting research and testing public policy interventions. Consent to a therapy or a research protocol must possess three features in order to be valid. It should be voluntarily expressed, it should be the expression of a competent subject, and the subject should be adequately informed. It’s highly unlikely that people subjected to the extended use and broadened application of welfare sanctions gave their informed consent to participate in experiments designed to test the theory of “loss aversion,” for example.

There is nothing to prevent a government deliberately exploiting a research framework as a way to test out highly unethical and ideologically-driven policies. How appropriate is it to apply a biomedical model of prescribed policy “treatments” to people experiencing politically and structurally generated social problems, such as unemployment, inequality and poverty, for example?

The increasing conditionality and politicisation of “truths”

The goverment often claim that any research revealing negative social consequences arising from their draconian policies, which they don’t like to be made public “doesn’t establish a causal link.” Recently there has been a persistent, aggressive and flat denial that there is any “causal link” between the increased use of food banks and increasing poverty, between benefit sanctions and extreme hardship and harm, between the work capability assessment and an increase in numbers of deaths and suicides, for example.

The government are referring to a scientific maxim: “Correlation doesn’t imply causality.”

It’s true that correlation is not the same as causation.

It’s certainly true that no conclusion may be drawn regarding the existence or the direction of a cause and effect relationship only from the fact that event A and event B are correlated. Determining whether there is an actual cause and effect relationship requires further investigation. The relationship is more likely to be causal if the correlation coefficient is large and statistically significant, as a general rule of thumb. (For anyone interested in finding out more about quantitative research methods, inferential testing and statistics, this is a good starting point – Inferential Statistics.)

Here are some minimal conditions to consider in order to establish causality, taken from Hills criteria:

- Strength: A relationship is more likely to be causal if there is a plausible mechanism between the cause and the effect.

- Coherence: A relationship is more likely to be causal if it is compatible with related facts and theories.

- Analogy: A relationship is more likely to be causal if there are proven relationships between similar causes and effects.

- Specificity: A relationship is more likely to be causal if there is no other likely explanation.

- Temporality: A relationship is more likely to be causal if the effect always occurs after the cause.

- Gradient: A relationship is more likely to be causal if a greater exposure to the suspected cause leads to a greater effect.

- Plausibility: A relationship is more likely to be causal if there is a plausible mechanism between the cause and the effect.

Hill’s criteria can be thought of as elements within a broader process of critical thinking in research, as careful considerations in the scientific method or model for deciding if a relationship involves causation. The criteria don’t all have to be met to suggest causality and it may not even be possible to meet them in every case. The important point is that we can consider the criteria as part of a careful and relatively unbiased research process. We can also take other precautionary steps, such as ensuring that there are no outliers or excessive uncontrolled variance, ensuring the populations sampled are representative and generally taking care in our research design, for example.

However, it is inaccurate to say that correlation doesn’t imply causation. It quite often does.

Furthermore, the government are implying that social research is valid only if it conforms to strict and archaic positivist criteria, and they attempt to regularly dismiss the propositions and research findings of social scientists as being “value-laden” or by implying that they are, at least. However, it may also be said that values enter into social inquiry at every level, including decisions to research a social issue or not, decisions to accept established correlations and investigate further, or not, which transforms research into a political act. (One only need examine who is potentially empowered or disempowered through any inquiry and note the government response to see this very clearly).

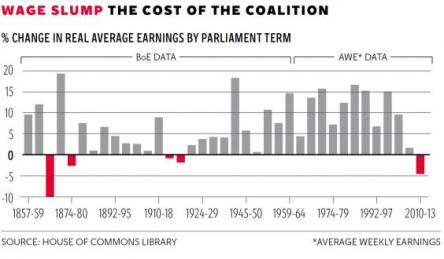

It’s noteworthy that when it comes to government claims, the same methodological rigour that they advocate for others isn’t applied. Indeed, many policies have clearly been directed by ideology and traditional Tory prejudices, rather than valid research and empirical evidence. For example, it is widely held by the Conservatives that work is the “only route out of poverty”. Yet since 2010, the decline in UK wage levels has been amongst the very worst in Europe. The fall in earnings under the Tory-led Coalition is the biggest in any parliament since 1880, according to analysis by the House of Commons Library, and at a time when the cost of living has spiralled upwards. Many people in work, as a consequence, are now in poverty, empirically contradicting government claims.

So what is positivism?

Positivism was a philosophical and political movement which enjoyed a very wide currency in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was extensively discredited during the twentieth century.

Auguste Comte (1798-1857,) who was regarded by many as the founding father of social sciences, particularly sociology, and who coined the term “positivism,” was a Conservative. He believed social change should happen only as part of an organic, gradual evolutionary process, and he placed value on traditional social order, conventions and structures. Although the notion of positivism was originally claimed to be about the sovereignty of positive (verified) value-free, scientific facts, its key objective was politically Conservative. Positivism in Comte’s view was “the only guarantee against the communist invasion.” (Therborn, 1976: 224).

The thing about the fact-value distinction is that those who insist on it being rigidly upheld the loudest generally tend to use it the most to disguise their own whopping great ideological commitments. In psychology, we call this common defence mechanism splitting. “Fact, fact, fact!” cried Mr Thomas Gradgrind. It’s a very traditionally Conservative way of rigidly demarcating the world, imposing hierarchies of priority and order, to assure their own ontological security and maintain the status quo, regardless of how absurd this shrinking island of certainty appears to the many who are exiled from it.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Comte’s starting point is the same as Hayek’s, namely the existence of a spontaneous order. It’s a Conservative ideological premise, and this is one reason why the current neoliberal Tory government of self-described “libertarian paternalists” embrace positivism without any acknowledgement of its controversy.

However, positivist politics was discarded half a century ago, as a reactionary and totalitarian doctrine. It’s is true to say that, in many respects, Comte was resolutely anti-modern, and he also represents a general retreat from Enlightenment humanism. His somewhat authoritarian positivist ideology, rather than celebrating the rationality of the individual and wanting to protect people from state interference, instead fetishised the scientific method, proposing that a new ruling class of authoritarian technocrats should decide how society ought to be run and how people should behave. This is a view that the current government, with their endorsement and widespread experimental application of nudge theory, would certainly subscribe to.

Science, correlation and causality

Much scientific evidence is based on established correlation of variables – they are observed to occur together. For example, correlation is used in Bell’s theorem to disprove local causality. The combination of limited available methodologies has been used together with the dismissing “correlation doesn’t imply causation” fallacy on occasion to counter important scientific findings. For example, the tobacco industry has historically relied on a dismissal of correlational evidence to reject a link between tobacco and lung cancer, especially in the earliest stages of the research, but there was a clearly and strongly indicated association.

Science is manifestly progressive, insofar as over time its theories tend to increase in depth, range and predictive power.

Established correlations in both the social and natural sciences may be regarded, then, as a starting point for further in-depth and rigorous research, with the coherence, comprehensiveness and verisimilitude of theoretical propositions increasing over time. This is basically a critical realist position, which is different from the philosophical positivism that dominated science and the social sciences two centuries ago, with an emphasis on strictly reductive empirical evidence and the verification principle (which is itself unverifiable).

Positivist epistemology has been extensively critiqued for its various limitations in studying the complexities of human experiences. One critique focuses on the positivist tendency to carry out studies from a “value-free” outsider perspective in an effort to maintain objectivity, whilst the insider or subjective perspective is ignored. There is no mind-independent, objective vantage point from which social scientists may escape the insider. A second critique is that positivism is reductionist and deterministic. It emphasises quantification and ignores and removes context, meanings, autonomy, intention and purpose from research questions by ignoring unquantifiable variables.

It therefore doesn’t extend explanations and understanding of how we make sense of the world. A third critique is that positivism entails generalisation of data which renders results inapplicable to individual cases; data are used to describe a population without accounting for significant micro-level or individual variation. Because of these and other problems, positivism lost much favour amongst sociologists and psychologists in particular.

Verification was never the sole criterion of scientific inquiry. Positivism probably lost much more methodological and epistemological currency in the social sciences than the natural sciences, because humans cannot be investigated in the same way as inert matter. We have the added complication of consciousness and [debatable] degrees of intentionality, so people’s behaviour is much more difficult to measure, observe and predict. There’s a difference between facts and meanings, human behaviours are meaningful and purposeful, human agency arises in contexts of intersubjectively shared meanings. But it does seem that prediction curiously becomes easier at macro-levels when we examine broader social phenomena, mechanisms and processes. (It’s a bit like quantum events: quite difficult to predict at subatomic level, but clarifying, with events apparently becoming more predictable at the level we inhabit and observe every day.)

Now, whilst correlation isn’t quite the same as “cause and effect”, it often strongly indicates a causal link, and what usually follows once we have established a correlation is further rigorous research, eliminating “confounding” variables and bias systematically (we do use rigorous inference testing in the social sciences). Correlation is used when inferring causation; the important point is that such inferences are made after correlations are confirmed as real and all causational relationships are systematically explored using large enough data sets.

The standard process of research and enquiry, scientific or otherwise, doesn’t entail, at any point, a flat political denial that there is any relationship of significance to concern ourselves with, nor does it involve withholding data and a refusal to investigate further.

Positivism and psychology

Positivism was most closely associated with a doctrine known as behaviourism during the mid-20th century in psychology. Behaviourists confined their research to behaviours that could be directly observed and measured. Since we can’t directly observe beliefs, thoughts, intentions, emotions and so forth, these were not deemed to be legitimate topics for a scientific psychology. One of the assumptions of behaviourists is that free-will is illusory, and that all behaviour is determined by the environment either through association or reinforcement. B.F. Skinner argued that psychology needed to concentrate only on the positive and negative reinforcers of behaviour in order to predict how people will behave, and everything else in between (like what a person is thinking, or their attitude) is irrelevant because it can’t be measured.

So, to summarise, behaviourism is basically the theory that human (and animal) behaviour can be explained in terms of conditioning, without appeal to wider socioeconomic contexts, consciousness, character, traits, personality, internal states, intentions, purpose, thoughts or feelings, and that psychological disorders and “undesirable” behaviours are best treated by using a system of reinforcement and punishment to alter behaviour “patterns.”

In Skinner’s best-selling book Beyond Freedom and Dignity, 1971, he argued that freedom and dignity are illusions that hinder the science of behaviour modification, which he claimed could create a better-organised and happier society, where no-one is autonomous, because we have no autonomy. (See also Walden Two: 1948: Skinner’s dystopian novel).

There is, of course, no doubt that behaviour can be controlled, for example, by threat of violence, actual violence or a pattern of deprivation and reward. Freedom and dignity are values that are intrinsic to human rights. Quite properly so. All totalitarians, bullies and authoritarians are behaviourists. Skinner has been extensively criticised for his sociopolitical pronouncements, which many perceive to be based on serious philosophical errors. His recommendations are not based on “science”, but on his own covert biases and preferences.

Behaviourism also influenced a positivist school of politics that developed in the 50s and 60s in the USA. Although the term “behavouralism” was applied to this movement, the call for political analysis to be modeled upon the natural sciences, the preoccupation with researching social regularities, a commitment to verificationism, an experimental approach to methodology, an emphasis on quantification and the prioritisation of a fact-value distinction: keeping moral and ethical assessment and empirical explanations distinct, indicate clear parallels with the school of behaviourism and positivism within psychology.

The political behaviouralists proposed, ludicrously, that normative concepts such as “democracy,” “equality,” “justice” and “liberty” should be rejected as they are not scientific – not verifiable or falsifiable and so are beyond the scope of “legitimate” inquiry.

Behaviourism has been criticised within politics as it threatens to reduce the discipline of political analysis to little more than the study of voting and the behaviour of legislatures. An emphasis on the observation of data deprives the field of politics of other important viewpoints – it isn’t a pluralist or democratic approach at all – it turns political discourses into monologues and also conflates the fact-value distinction.

Every theory is built upon an ideological premise that led to its formation in the first place and subsequently, the study of “observable facts” is intentional, selective and purposeful. As Einstein once said: “the theory tells you what you may observe.”

The superficial dichotomisation of facts and values also purposefully separates political statements of what is from what ought to be. Whilst behavouralism is itself premised on prescriptive ideology, any idea that politics should include progressive or responsive prescriptions – moral judgements and actions related to what ought to be – are summarily dismissed.

Most researchers would agree that we ought to attempt to remain as objective as possible, perhaps aiming for a relative value-neutrality, rather than value-freedom, when conducting research. It isn’t possible to be completely objective, because we inhabit the world that we are studying, we share cultural norms and values, we are humans that coexist within an intersubjective realm, after all. We can’t escape the world we are observing, or the mind that is part of the perceptual circuit.

But we can aim for integrity, accountability and transparency. We can be honest, we can critically explore and declare our own interests and values, for example. My own inclination is towards value-frankness, rather than value-freedom – we can make the values which have been incorporated in the choice of the topic of research, and of the formulation of hypotheses clear and explicit at the very outset. The standardised data collection process itself is uncoloured by personal feelings (that is, we can attempt to collect data reliably and systematically.) However, the debate about values and the principle of objectivity is a complex one, and it’s important to note that symbolic interactionists and post modernists, amongst others, have contended that all knowledge is culturally constructed. (That’s a lengthy and important discussion for another time.)

Nudge: from meeting public needs to prioritising political needs

The idea of “nudging” citizens to do the “right thing” for themselves and for society heralds the return of behaviourist psychopolitical theory. Whilst some theorists claim that nudge is premised on notions of cognition, and so isn’t the same as the flat, externalised stimulus-response approach of behaviourism, my observation is that the starting point of nudge theory is that our cognitions are fundamentally biased and faulty, and so the emphasis of nudge intervention is on behaviour modification, rather than on engaging with citizen’s cognitive or deliberative capacities.

In other words, our tendency towards cognitive bias(es) render us incapable of rational decision-making, so the state is bypassing democratic engagement and prescribing involuntary and experimental behavioural change to “remedy” our perceived cognitive deficits.

Behaviourists basically stated that only public events (behaviours of an individual) can be objectively observed, and that therefore private events (intentions, thoughts and feelings) should be ignored. The paternal libertarians are stating that our cognitive processes are broken, and should be ignored. What matters is how people behave. It’s effectively another reductionist, instrumental stimulus-response approach based on the same principles as operant conditioning.

Nudge is very controversial. It’s experimental use on an unconsenting population has some profound implications for democracy, which is traditionally based on a process of dialogue between the public and government, ensuring that the public are represented: that governments are responsive, shaping policies that address identified social needs. However, Conservative policies are no longer about reflecting citizen’s needs: they are increasingly all about instructing us how to be.

The context-dependency and determination of value-laden nudge theory

Libertarian paternalists are narrowly and uncritically concerned only with the economic consequences of decisions within a neoliberal context, and therefore, their “interventions” will invariably encompass enforcing behavioural modifiers and ensuring adaptations to the context, rather than being genuinely and more broadly in our “best interests.” Defining human agency and rationality in terms of economic outcomes is extremely problematic. And despite the alleged value-neutrality of the new behavioural economics research it is invariably biased towards the status quo and social preservation rather than progressive social change.

At best, the new “behavioural theories” are merely theoretical, at a broadly experimental stage, and therefore profoundly limited in terms of scope and academic rigour; as a mechanism of explanation and in terms of capacity for generating comprehensive and coherent accounts and understandings of human motivation and behaviour.

Furthermore, in relying upon a pseudo-positivistic experimental approach to human cognition, behavioural economists have made some highly questionable ontological and epistemologial assumptions: in the pursuit of methodological individualism, citizens are isolated from the broader structural political, economic and sociocultural and established reciprocal contexts that invariably influence and shape an individuals’s experiences, meanings, motivations, behaviours and attitudes, causing a deeply problematic duality between context and cognition.

Yet many libertarian paternalists reapply the context they evade in explanations of human behaviours to justify the application of their theory in claiming that their “behavioural theories” can be used to serve social, and not necessarily individual, ends, by simply acting upon the individual to make them more “responsible.” But “responsible” is defined only within the confines of a neoliberal economic model. (See, for example: Personal Responsibility and Changing Behaviour: the state of knowledge and its implications for public policy, David Halpern, Clive Bates, Geoff Mulgan and Stephen Aldridge, 2004.)

In other words, there is a relationship between the world that a person inhabits and a person’s perceptions, intentions and actions. Any theory of behaviour and cognition that ignores context can at best be regarded as very limited and partial. Yet the libertarian paternalists overstep their narrow conceptual bounds, with the difficulty of reconciling individual and social interests somewhat glossed over. They conflate “social interests” with neoliberal outcomes.

The ideological premise on which the government’s “behavioural theories” and assumptions about the negative impacts of neoliberalism on citizens rests is fundamentally flawed, holding individuals responsible for circumstances that arise because of market conditions, the labor market, political decision-making, socioeconomic constraints and the consequences of increasing “liberalisation”, privatisation and marketisation.

Market-based economies both highly value and extend competitive individualism and “efficiency”, which manifests a highly hierarchical social structure, and entails the adoption of economic Darwinism. By placing a mathematical quality on social life (Bourdieu, 1999), neoliberalism has encouraged formerly autonomous states to regress into penal states that value production, competition and profit above all else, including attendance to social needs and addressing arising adverse structural level constraints, the consequences of political decision-making and wider socioeconomic issues, such as inequality and poverty.

As a doxa, neoliberalism has become a largely unchallenged reality. It now seems almost rational that markets should be the allocators of resources; that competition should be the primary driver of social problem-solving, innovation and behaviour, and that societies should be composed of individuals primarily motivated by economic conditions and their own economic productivity. Despite the Conservative’s pseudo-positivist claims of value-neutrality, the economic system is being increasingly justified by authoritarian moral arguments about how citizens ought to act.

The rise of a new political behaviourism reflects, and aims at perpetuating, the hegemonic nature of neoliberalism.

Image courtesy of Tiago Hoisel