Philip Alston, UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, travelled across the country to examine the impact of austerity. He came to Newcastle, visiting a West End foodbank, among other places. He concluded that Universal Credit and other ‘reforms’ are “entrenching high levels of poverty and inflicting unnecessary misery.” According to his research, 14 million people – a fifth of the population – live in poverty. Four million of these are more than 50% below the poverty line, and 1.5 million are destitute, unable to afford basics essentials. Alston said: “In the fifth richest country in the world, this is not just a disgrace, but a social calamity and an economic disaster, all rolled into one.”

Universal Credit has been designed to change the relationship between the state and citizens. It is about altering the public’s expectations of the role of government. It is about deepening targeted austerity. It is also about cutting social security and dismantling the welfare state.

The one-off £10 payment, which was designed to be an extra boost to families over the festive period, has been axed under Universal Credit, which demonstrates very well what kind of “mean spirited” intentions went into the design of system. I rang the Department for Work and Pensions press office to confirm this and it was affirmed that the cut has happened. A spokesperson said: “Universal Credit claimants have never received a one-off December payment, but many disabled people on Universal Credit will be better off on average by £100 month than when they received Employment and Support Allowance (ESA).”

Yesterday, someone I know through social media sent me a copy of a notice they got when they logged onto the Universal Credit system. It said:

So, if an employer pays his employees early in December due to the Christmas holiday period or pays a Christmas bonus, people may well receive a reduced Universal Credit payment in December or none at all. This is due the fact that the unadaptable system cannot cope with people being paid twice in one assessment period, even though it isn’t an additional payment, it is simply an early payment.

Judicial reviews

The controversial Universal Credit programme is to undergo another legal challenge at the High Court in London, as evidence mounts further that the new social security system will leave thousands of people already on low incomes significantly worse off. Four women are taking the government to court because of this reason.

This is the second judicial review of Universal Credit. It follows the High Court’s finding in June that the Universal Credit system was unlawfully discriminating against severely disabled people. Those who had qualified for the support component of income-related Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) are also eligible for a disability premium. However, as a result of the abolition of both the severe disability premium (SDP) and enhanced disability premium (EDP) under Universal Credit rules, according to the disability charity, Scope, the cut to the disability income guarantee will see disabled people lose as much as £395 a month.

The high court judge ruled that the Department for Work and Pensions unlawfully discriminated against two severely disabled men who both saw their benefits dramatically reduced when they moved Local Authority – one of them because of the bedroom tax – and were required to claim Universal Credit. The court found that the implementation of Universal Credit and the absence of any ‘top up’ payments for this vulnerable group as compared to others constitutes discrimination contrary to the European Convention on Human Rights.

Since the court case, Esther McVey, then Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, announced that no severely disabled person in receipt of the SDP will be made to move onto Universal Credit until transitional protection is in place. She also committed to compensating those like the two claimants who have lost out on their disability premium because they had to claim Universal Credit.

Yet despite this, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions has sought permission to appeal, maintaining that there was “nothing unlawful” with the way the claimants were treated.

The second judicial review comes amid mounting concern over Universal Credit, which academics have described as a “complicated, dysfunctional and punitive” system pushing people into debt and rent arrears.

Last week it emerged that more than half of people denied Universal Credit were found to be entitled to it when their cases were investigated, prompting fresh demands for the national rollout of the new system to be halted. It’s something of an irony, given that Universal Credit was introduced in 2013 with the stated intention of bringing “fairness and simplicity” to Britain’s social security system.

Now, four plaintiffs say the flaw, which relates to the way Universal Credit monthly payments are calculated, disproportionately affects working parents with children and leaves claimants with a “dramatically fluctuating income” and unable to budget from month to month.

In one case uncovered by the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) reported by The Guardian, a family’s monthly payment swung from £1,185 to zero, making budgeting impossible. One of the women has said that as well as being irrational, the payment system is also discriminatory as it disproportionately affects single parents, who are predominantly female. Last month, MP Frank Field said the system was driving some women in his constituency into sex work in a bid to avoid absolute poverty.

A single mother says she was forced to turn down a promotion and use a food bank after issues with the assessment period for the new benefit system made it “impossible to budget”.

She said: “I invested £40,000 in higher education studies so that I could become an occupational therapist and it’s great that I’ve got my degree but I have had to put my career hopes on hold because of Universal Credit.

“I had to go to a food bank and I took out an advance that I am still paying back. I took two jobs – as a PA and a waitress – which I could do without the education I invested in but which had paydays which don’t clash with my assessment period. I wanted to become free of welfare through my chosen profession but Universal Credit is holding me back from that.”

Although she had originally wanted a healthcare job, which was relevant to her degree and would move her nearer earnings that would eventually take her out of the social security system altogether, she found that the NHS and other health organisations mostly paid salaries at the end of the working month so she would face the same assessment period trap.

She left the council and initially took two part time jobs, and she now has one part time job.

Her solicitor, Carla Clarke of Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG), said: “Universal Credit is promoted as a benefit that ‘incentivises’ work but in practice its rigid assessment period system undercuts that claim.

“Our clients have been left repeatedly without money for family essentials simply because of the date of their paydays.

“One of them, for example, did her utmost to find a workaround but ultimately had to decline a promotion in a job with good prospects when her then contract came to an end just to escape the trap.

“We say that the DWP’s refusal to alter our clients’ assessment period dates to avoid this problem discriminates against working parents – one of the two groups who are entitled to a work allowance – as well as being irrational and undermining one of the stated purposes of universal credit – to make sure that ‘work always pays’.”

CPAG argues that the DWP refusal to alter Woods’ assessment period dates to avoid the problem discriminated against working parents – one of the two groups who are entitled to a work allowance – as well as being “irrational and undermining.”

Clarke added “This is a fundamental defect in Universal Credit and an injustice to hard-working parents and their children that must be put right for our clients and everyone else affected”.

Another of the women involved in the court case is paid by her employer on the last working day of each month. However, the Universal Credit assessment periods run from the last day of each month, meaning that if she is paid before the last day of the month she is assessed as having been paid twice that month.

Lawyers from the legal firm supporting Johnson at LeighDay, say: “This has resulted in her receiving fluctuating Universal Credit payments throughout the year, making it very hard to budget from one month to the next.”

They add: “It has also caused her to be around £500 worse off annually due to the fact that she is entitled to ‘work allowance’ as a parent.

“The work allowance is a disregard of £198 per month of a parent’s monthly earnings so in months where she is treated as having no earned income, she loses the whole benefit of the work allowance. In months where she is treated as having double income, she does not receive any extra work allowance.”

Legal aid for social security appeals is almost entirely gone. People adversely affected by unfair decisions are effectively being denied support in accessing justice. It’s difficult to see this as anything other than a planned and coordinated attack on people’s most basic human and democratic rights.

Universal Credit increases and extends the risk of domestic abuse

Couples who live together are required to make a single household claim for Universal Credit. Their individual entitlements are calculated—based on household income—and combined into a single payment, paid into one account only. In December 2017, 55,000 couple households, including 40,000 with dependent children, were claiming Universal Credit. Once it is fully rolled out, around 2.9 million couple households will claim it. MPs have warned that Universal Credit increases the risk of allowing domestic abusers to exert financial control over victims.

A critical report by the Work and Pensions committee in August said the way Universal Credit is paid per household means that perpetrators could too easily take control of the entire budget, leaving vulnerable women and their children dependent on an abusive partner to survive. Frank Field, Labour chair of the committee, said: “This is not the 1950s. Men and women work independently, pay taxes as individuals, and should each have an independent income.

“Not only does Universal Credit’s single household payment bear no relation to the world of work, it is out of step with modern life and turns back the clock on decades of hard-won equality for women.”

He added “The government must acknowledge the increased risk of harm to claimants living with domestic abuse it creates by breaching that basic principle, and take the necessary steps to reduce it.”

Ministers were urged by the committee to consider overhauling the system so payments are automatically split between couples, as victims face “great danger” if they request their own payments under current rules.

The report said: “Universal Credit currently only allows claims to be split between partners in ‘exceptional circumstances’.

“The DWP itself recognises the risk that requesting such an arrangement poses to survivors. The perpetrator will realise the survivor has requested the split when their own payments fall, potentially putting them in great danger.

“In light of this risk, many survivors simply will not request a split.”

The committee also suggested the main carer of children should automatically receive the whole payment, while officials explore ways to develop a split payment scheme. JobCentres must set aside private rooms for vulnerable claimants and appoint a domestic violence specialist to deal with specific claims, the report also said.

Katie Ghose, chief executive of Women’s Aid, said: “We have long been warning that Universal Credit risks making the domestic abuse worse for survivors and putting an additional barrier in the way of them escaping the abuse.

“That’s why we welcome the committee’s report and urge the government to take action to make Universal Credit safe for survivors.

“We know from our work with survivors that abusers will exploit single household payments, yet applying for a split payment can also be dangerous. If the abuser finds out that a survivor has made an application, she may be at further risk.”

Domestic abuse is hugely complex, and the training Work Coaches currently receive leaves them ill-equipped to perform this vital function. Under Universal Credit, claimants living with domestic abuse can face seeing their entire monthly income—including money meant for their children—go into their abusive partner’s account. There is no guarantee that any of the money they need to live or care for their children will reach them. That risks them remaining dependent on their abusive partner and making it much harder for them to leave, should the opportunity present itself.

Yet the Scottish Parliament has passed legislation which requires the Scottish Government to introduce split payments by default.

Universal Credit is perpetuating gender inequality – an issue that the Equality and Human Rights Commission have also raised concerns about. If money is paid into an abuser’s account, that compromises a woman’s financial autonomy. Their recent report recommends:

- offering Universal Credit as single payments to individuals rather than joint payments to avoid exacerbating financial abuse for women experiencing domestic violence

- reconsidering the ‘spare room subsidy’ regulations which discriminate against survivors of domestic abuse who have safe rooms.

But the government justifies the policy by claiming that few couples manage their finances separately. They argue that paying one benefit into a single bank account means families can make decisions about their household finances without government interference. However, this assessment ignores the realities of women trapped in controlling relationships.

Two child policy – regarding children as a commodity, and some say, eugenics by stealth

This policy restricts support through means-tested family benefits to two children only and affects the child tax credit payable for all third or subsequent children born after April 2017 and all new claims for Universal Credit, whenever they were born. In doing so, the two-child policy breaks the fundamental link between need and the provision of minimum support and implies that some children, by virtue of their birth order, are less deserving of support. It is a very large direct cut to the living standards of the poorest families of up to £2780 per child, per year.

In 2015/16 — the latest year for which data is available — 27 per cent of households with children had more than two children, representing more than 1 in 3 children in poverty (after housing costs). The risk of poverty is already 39 per cent for households (after housing costs) with three or more children compared with 26 per cent for one- and 27 per cent for two-child families. The most recent statistics reveal that during the first year of operation, 59% of the 73,500 families who lost financial support for a third child were in work. Nine per cent of UK claimant households with three or more children were affected.

A number of groups in the population are particularly likely to be hard hit by the policy, including Orthodox Jews, Pakistani and Bangladeshi families, and Roman Catholics. It will also hit large families bereaved by the loss of a parent, divorced families, and all large families falling upon hard times and needing to claim means-tested support.

Originally there were no intentions to make exceptions to the two-child policy, but the government was forced to make concessions for, among others, third and subsequent children under kinship care and those conceived as a result of rape — which in itself forces highly sensitive disclosure. A number of women’s rights and rape support organisations have raised serious concerns about the third-party evidence model for the rape/coercion exception and the risk that women claiming this exception will be exposed to further trauma and gross breaches of privacy.

The so-called rape clause has been condemned by campaigners, who say it is outrageous that a woman must account for the circumstances of her rape to qualify for support. The SNP MP Alison Thewliss called it “one of the most inhumane and barbaric policies ever to emanate from Whitehall”.

A government spokesperson said: “The policy to provide support in child tax credit and universal credit for a maximum of two children ensures people on benefits have to make the same financial choices as those supporting themselves solely through work.

The rationale for the two-child limit was to reduce the deficit by £1.36 billion per year by 2020/21. But the government also sought to justify it on the basis that they are hoping to ‘change behaviours’ — hoping to ‘encourage parents to reflect carefully on their readiness to support an additional child’. Yet, the savings to be made from the policy are quite modest in the context of the austerity cuts of £27 billion per year since 2010.

The rollout of Universal Credit will increase the number of families affected. All new claims for the benefit after February 2019 will have the child element restricted to two children in a family, even if they were born before the policy was introduced.

The government estimated 640,000 families will lose support as a direct result of the proposed changes. The Children’s Society estimate that the total loss of a child element plus the family element of child tax credit will mean that a family with three children will lose up to £3,325 per year. A family with four children will lose up to £6100. Troublingly, disabled children will also be affected by this measure on top of the major cuts in children’s disability support through Universal Credit.

Jamie Grier, the development director at the welfare advice charity Turn2us, has spoken out about mothers in low income families faced with the agonising choice of terminating wanted pregnancies already, because of their financial circumstances.

Alison Garnham, the chief executive of Child PovertyAction Group, said: “An estimated one in six UK children will be living in a family affected by the two-child limit once the policy has had its full impact. It’s a pernicious, poverty-producing policy.”

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has projected that 600,000 more children will live in absolute child poverty by 2020/21 compared with 2015/16 — all of them in families with three or more children. The absolute child poverty rate is to increase over that period from 15.1 per cent to 18.3 per cent. The two-child limit accounts for around a third of this impact. Absolute poverty is when people can’t meet one or more of their basic survival needs.

The policy is extremely likely to contravene human rights treaties to which the UK is a signatory, including those relating to women’s reproductive rights and protection from religious and gender-based discrimination contrary to Article 16 of the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

It would also discriminate against groups with a conscientious objection to contraception and abortion, or for whom large families are a central tenet of faith, in breach of Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Furthermore, it fails to give primary consideration to the best interest of the child in contravention of Article 3(1) of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights raised a specific concern about the effect of cuts to social security on the standard of living enjoyed by families with two or more children in the Concluding Observations of its recent review of the UK’s compliance with the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The policy is going to be challenged in the courts on discrimination grounds and may well reach the Supreme Court and European Court of Justice.

Context and policy intent

Universal credit is the controversal reform of the social security system, rolling together six so-called “legacy” benefits (including unemployment benefit, employment and tax credits and housing benefit) into one benefit paid monthly to claimants, to “make work pay.”

However, at a time of stagnant wages and ever-increasing living costs, the government slogan ‘making work pay’ is certainly not about a national wage increase. It’s rather more about neoliberal supply-side ideology. Supply-side policies include the promotion of greater competition in labour markets, through the removal of what are deemed ‘restrictive practices’, and labour market rigidities, such as the protection of employment and workers’ rights. For example, as part of neoliberal supply-side reforms in the 1980s, trade union powers were greatly reduced by a series of measures including limiting workers’ ability to call a strike, and by enforcing secret ballots of union members prior to strike action. More recently the Conservatives have again made substantial legislative changes that undermine the role of trade unions.

Deregulation and privatisation of state industry and services are also components of supply-side economics. Supply-side measures have a negative effect on the distribution of income. For example, lower taxes rates for the wealthiest, lower wages for workers, reduced union power, and privatisation have all contributed to a widening of the gap between rich and poor citizens. Universal Credit facilitates a supply-side labour market, it coerces people into accepting low paid, insecure work. Any work.

People claiming Universal Credit do not get a say in the kind of work they take on. If people don’t comply with Universal Credit conditionality they are generally sanctioned. This entails a loss of welfare support for between four weeks and up to a maximum of three years for refusing to take a job or prescribed community work.

Some economists argue that a lack of bargaining power because union membership has been in long term decline – is leading to fewer widespread agreements on earnings increases, which has served to keep wages stagnant. A lack of employee confidence and certainty following the recession and fears, then, over job losses has also led to fewer demands for rises.

Given that collective bargaining has been politically undermined, it is particularly outrageous that the government has introduced sanctions for those on low pay and in work, for a failure to single handedly negotiate better pay or an increase in working hours with their employer.

Perhaps we should ask “making work pay” for whom?

It’s interesting that the government have outlined what Universal Credit means for employers, indicating the intent behind the policy is not about mitigating poverty. It’s about employers “having access to a more flexible and responsive workforce, which can help your business with the challenges of filling vacancies.

“Universal Credit payments automatically adjust each month based on the real time PAYE information you report to HMRC, so it’s important that you report this information accurately and on time.”

The ‘business friendly’ government says “Universal Credit increases the financial incentive of work and provides employers like you with a more flexible workforce.”

So while employers are promised a workforce that will accept more, in terms of conditions, rates of pay and job security, the same workforce is being set up to fail when trying to negotiate more pay and longer hours by the government’s ‘business friendly’ deregulation. And failure can mean facing having their Universal Credit cut via sanctions.

It does go on to say on the site that “Jobcentre Plus work coaches will encourage claimants to discuss with their employers how they can increase their chances of earning more. This could be by improving their skills which may help them to take on more responsibilities. You may find your employees asking for more hours or for help with building their skills. You can play a role in this – helping your business become more productive.”

So, employers “can” but workers “must”, despite the substantial imbalance of power, made worse by the fact that workers are being coerced into “flexibility”. That invariably means lowering their expectations of employers and of the conditions of their employment.

The publicly stated aim of Universal Credit, for which there was orginally general support across the political divide, was to simplify the welfare system, making it more “efficient” and easy to access at a single claim point. Despite these claims, many have complained that Universal Credit is bafflingly complex, unreliable and difficult to manage, particularly if you are without internet access, and that Universal Credit staff are often poorly trained. The combination of these problems is leaving people in precarious and very vulnerable circumstances.

For families and lone parents in particular, there are barriers to taking short term low paid work, as continuity of income and availability of childcare are key priorities for parents.

The Conservatives have also claimed that the new benefit will provide incentives for people to work rather than stay on benefits. Perhaps it’s worth noting that only 34% of people claiming state welfare are of working age, the majority – 66% – are people of pension age.

The government say “It is intended that by introducing a single in-work and out-of-work benefit, previous barriers to employment such as taking up temporary employment or fewer hours are removed, therefore making it easier for claimants to take up any work and changing claimant perceptions of work and welfare, and their employment behaviours, at an individual and household level.”

The Conservatives go on to claim that employment levels are at a record high, because Universal Credit is “working”. Some 80% of men are in work, the joint highest employment rate since 1991. And over 70% of women are in work, the highest employment rate since records began in 1971. But that increase is down, partly, to state pension age changes which mean fewer women are retiring between the ages of 60 and 65.

However, as I have indicated, the structure of the employment market also matters. Zero hours contracts and hyper-flexible employment might be welcomed by some for the options they offer, but they work against collective bargaining agreements on earnings, keeping wages low. And low wages, not lack of incentives, are the reason why people need welfare support. The trade union wage gap, the difference in earnings of union members compared with non-members, is 16.9% in the public sector and 7.1% in the private sector (which employs well over 80% of people). There cannot be any genuine economic ‘bounce back’ until the UK’s decade-long stagnation in wages ends.

Universal Credit was supposedly intended as a payment to help people with living costs. It’s for those on a low income or out of work. As of February this year, the number of people on Universal Credit was 770 thousand. Of these people 300 thousand were in employment. The intention embedded in the design of Universal Credit to force up to a million low-paid workers to seek more hours or move to higher-paid jobs, under threat of financial sanctions (in-work conditionality), is another ticking bomb.

It is being introduced in stages across the country. People claiming Universal Credit receive a single monthly household payment, paid into a bank account in the same way as a monthly salary; support with housing costs will usually go direct to the person claiming as part of their monthly payment.

People will usually make a claim for Universal Credit online, during which initial claim verification will take place. This entails people providing evidence of their identity. However, there have been some problems highighted with the government’s verification framework.

MP for Liverpool Walton, Dan Carden, called on the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) to postpone the roll-out of Universal Credit in his constituency until after Christmas and highlighted an issue with people having to pay out for a driving licence as one of many administrative problems with the new system.

In a letter to the secretary of state, Amber Rudd MP, Carden said: “We have families experiencing poverty on an unprecedented scale and now facing further avoidable hardship in the run up to Christmas.

“I have now been informed that job centres across Liverpool are advancing payments to my constituents to obtain provisional driving licences for the purposes of identification and then deducting the cost from their benefits.

“Constituents are also having to pay for postal orders, passport photographs and postage, just to obtain provisional licences.”

He explained that the DVLA says there is a five-week wait for provisional licences, and highlighted the delays before the first payments are made when someone is transferred on to Universal Credit.

The controversial benefit is being rolled out in many parts of Liverpool this week. Carden added: “Continuing with this roll-out will leave many of the most vulnerable families in Liverpool Walton destitute by Christmas and I am therefore asking you to intervene as a matter of urgency.”

Rudd’s response was to say Carden was ‘scaremongering’, and she denied that ID was needed to claim Universal Credit. However, it seems she failed to bother checking her own government’s web site for advice and evidence. The site which outlines how to claim Universal Credit completely contradicts Rudd’s claims, it says on the government’s site:

When people apply for Universal Credit they are asked to verify their identity online via the GOV.Verify service.

To do so, you need either;

- A valid UK driving license

- A valid UK passport.

On the government document it says “Universal Credit cannot be paid to a claimant whose identity has not been verified. Failure to provide identity documentation means that there is no valid claim.”

Of course this creates significant problems for those without the required documents. Their Universal Credit claim cannot go ‘live’ without conforming to the ID verification framework. People generally can’t get an advance because their claim isn’t live. Once they’ve received their new ID document, (takes around 6-8 weeks usually), it’s then a further 5 weeks (at least) until their first Universal Credit payment. That’s a very long time to go without support that is intended to meet people’s most basic living needs: food, fuel and shelter.

According to the government web site, you can only apply for an advance on your first payment if you have already verified your identity. It says:

You can apply for an advance payment in your online account or through your Jobcentre Plus work coach.

You’ll need to:

- explain why you need an advance

- verify your identity (you do this online when you submit your Universal Credit claim or at your first Jobcentre Plus interview)

- provide bank account details for the advance (talk to your work coach if you cannot open an account.)

The claim date is the date that a claimant completes this process and submits their claim. After making a claim, an initial interview will take place with the claimant, where the eligibility for Universal Credit will be confirmed and the claimant will accept a Claimant Commitment. Failure to comply with the Commitment without ‘good reason’ will result in a sanction. What constitutes a ‘good reason’ unfortunately varies from area to area and even among advisors in the same building. One of the many criticisms of welfare sanctions is how arbitrary they are. Universal Credit is a far stricter regime than the previous ones, and indications are that people are being sanctioned more frequently.

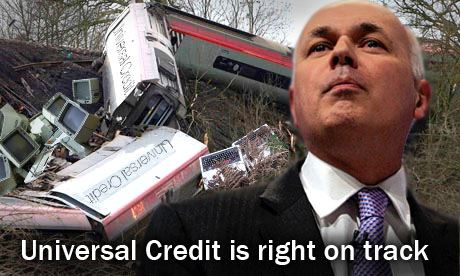

The Universal Credit project was passed through legislation in 2011 under the patronage of its loudest champion, former secretary of state for work and pensions Iain Duncan Smith. The plan was to roll it out across the UK by 2017. However, a series of management failures, expensive IT blunders and design faults mean it has fallen at least five years behind schedule.

Under the current schedule it will be fully implemented to include about 7 million claimants by 2022-23, when it is estimated that it will account for around £63bn of spending. A substantial proportion of that is due to administration blunders. Earlier this year, the National Audit Office said “The benefits that it set out to achieve through Universal Credit, such as increased employment and lower administration costs, are unlikely to be achieved.”

The administrative cost of every Universal Credit claim is an eye-watering £699 per case against an ultimate target of just £173, others in the field are calling to stop this utter shambles now and reconsider all options.

The Department is seriously criticised for “a lack of regard in failing to understand the hardship faced by some claimants”. Forget normal Whitehall tact, here are eight years of unrelenting failure, ploughing on despite alarms as costs rose to £2bn. One of the most urgent needs is to restore the £23bn that George Osborne cut from the budget, which is due to cause a record 37% of children in poverty by 2022, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. That’s likely to be a conservative estimate.

Despite a few minor changes, such as shortening the waiting period by a week, huge underlying problems remain with Universal Credit. Multibillion-pound cuts to work allowances imposed by the former chancellor have left it hollowed out. According to the Resolution Foundation thinktank, Universal Credit will leave about 2.5 million low-income working households more than £1,000 a year worse off. Reversing those cuts requires a political decision, not more tinkering around the edges and technical fixes.

Universal Credit is paid monthly, in arrears, so people have to wait one calendar month from the date they submitted their application before their first UC payment is made. This is called the assessment period. People then have to wait up to seven days for the payment to reach your bank account. That is of course providing everything goes right.

So far, the ‘customer’ experience of Universal Credit for too many people (and other stakeholders, such as landlords) has been utterly dismal. Critics argue that Treasury cuts to the benefit mean it is now far less likely to incentivise people to move into work, or to work more hours – what the Conservatives call ‘in-work progression’. As a result of cuts, Universal Credit is significantly less generous than originally intended, leaving many claimants worse off when they move on to it than they were while claiming legacy benefits. Added to that are design flaws and administrative glitches that put poorer claimants especially at heightened risk of hunger, debt and rent arrears, ill-health and homelessness.

Their report is intended to help the Council and partners to further develop the approach to supporting those affected by current and future welfare reforms.

It builds on Sheffield Hallam University research published in March 2016 which suggested that welfare reforms have cost the city’s economy the equivalent of £157M per year, set to rise to £292M per year by 2020. Liverpool City Council has had a 58% cut in central government funding since 2010 and has to find another £90M in savings by 2020, is having to use around £7M of those reduced funds to help with rent top ups and crisis payments.

Liverpool Food People are part of a food insecurity sub group that reports into The Mayoral Action Group on Fairness and Tackling Poverty – food has been identified as one of the basic needs – and a recommendation within the report is that action to address food poverty and fuel poverty is coordinated across the city and that research is carried out on the level of food insecurity (both moderate and severe) across the city.

New research conducted for Gateshead council concludes that Universal credit has become a serious threat to public health after the study revealed that the stress of coping with the new benefits system had so profoundly affected peoples’ mental health that some considered suicide.

The researchers found overwhelmingly negative experiences among vulnerable citizens claiming Universal Credit, including high levels of anxiety and depression, as well as physical problems and social isolation, all of which was exacerbated by hunger and destitution.

The Gateshead study comes as the United Nation’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, prepares to publish a report of the impact of Conservative austerity in the UK. Alston has been collecting evidence and testimonies on the effects of the welfare reforms, council funding cuts, and Universal Credit during a two-week visit of the UK.

This research is highly likely to raise fresh calls for the system’s rollout to be halted, or at the very least, paused to attempt to fix the fundamental design flaws and ensure adequate protections are in place for the most vulnerable people claiming it.

Approximately 750,000 chronically ill and disabled claimants are expected to transfer on to Universal Credit from 2019. Yet earlier this year, the first legal challenge against Universal Credit found that the government unlawfully discriminated against two men with severe disabilities who were required to claim the new benefit after moving into new local authority areas. Both saw their benefits dramatically reduced when they moved to a different Local Authority and were required to claim Universal Credit instead of Employment and Support Allowance.

The study findings are yet another indication of how unfit for purpose Universal Credit is. Six of the participants in the study reported that claiming Universal Credit had made them so depressed that they considered taking their own lives. The lead researcher, Mandy Cheetham, said the participant interviews were so distressing she undertook a suicide prevention course midway through the study.

The report says: “Universal Credit is not only failing to achieve its stated aim of moving people into employment, it is punishing people to such an extent that the mental health and wellbeing of claimants, their families and of [support] staff is being undermined.”

One participant told the researchers: “When you feel like ‘I can’t feed myself, I can’t pay my electric bill, I can’t pay my rent,’ well, all you can feel is the world collapsing around you. It does a lot of damage, physically and mentally … there were points where I did think about ending my life.”

An armed forces veteran said that helplessness and despair over Universal Credit had triggered insomnia and depression, for which he was taking medication. “Universal Credit was the straw that broke the camel’s back. It really did sort of drag me to a low position where I don’t want to be sort of thrown into again.”

Unsurprisingly, the report concludes that Universal Credit is actively creating poverty and destitution, and says it is not fit for purpose for many people with disabilities, mental illness or chronic health conditions. It calls for a radical overhaul of the system before the next phase of its rollout next year.

Alice Wiseman, the director of public health at Gateshead council, which commissioned the study, said: “I consider Universal Credit, in the context of wider austerity, as a threat to the public’s health.” She said many of her public health colleagues around the country shared her concerns.

Wiseman said that Universal Credit is “seriously undermining” efforts to prevent ill-health in one of the UK’s most deprived areas.

She added “This is not political, this is about the lives of vulnerable people in Gateshead. They are a group that should be protected but they haven’t been.”

The qualitative study focused on those claimants with disabilities, mental illness and long-term health conditions, as well as homeless people, veterans and care leavers.

The respondents found that compared to the legacy benefits, Universal Credit is less accessible, remote, inflexible, demeaning and intrusive. It was less sensitive to claimants’ health and personal circumstances, the researchers said. This heightened peoples’ anxiety, sense of shame, guilt, and feelings of loss of dignity and control.

The Universal Credit system itself was described by those claiming it as dysfunctional and prone to administrative error. People experienced the system as “hostile, punitive and difficult to navigate,” and struggled to cope with payment delays that left them in debt, unable to eat regularly, and reliant on food banks.

The government claimed that people making a new claim are expected to wait five weeks for a first payment. That’s a long time to wait with no money for basic living requirements. However, the average wait for participants on the study was seven and a half weeks, with some waiting as long as three months. Researchers were told of respondents who were so desperate and broke they turned to begging or shoplifting.

Wiseman made a point that many campaigners have made, and said that alongside the human costs, Universal Credit was placing extra burdens on NHS and social care, as well as charities such as food banks. It also affected the wellbeing of advice staff, who reported high stress levels and burnout from dealing with the fallout on those claiming the benefit.

Guy Pilkington, a GP in Newcastle said that the benefits system had always been tough, but under Universal Credit, those claiming faced a higher risk of destitution.

“For me the biggest [change] is the ease with which claimants can fall into a Victorian-style system that allows you to starve. That’s really shocking, and that’s new,” he said.

A spokesperson for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) said: “This survey of 33 claimants doesn’t match the broader experience of more than 9,000 people receiving Universal Credit in Gateshead, who are taking advantage of its flexibility and personalised support to find work.”

“We have just announced a £4.5bn package of support so people can earn £1,000 more before their credit payment begins to be reduced, and we are providing an additional two weeks’ payments for people being moved from the old system.”

That will still leave people with nothing to live on or to cover their rent for at least three weeks. The study focused on those less likely to be able to work – people with disabilities, mental illness or chronic health conditions. The DWP failed to recognise that this group have different needs and experiences than the broader population, which leave them much more likely to become vulnerable when they cannot meet their needs.

Vulnerable people are suffering great harm and some are dying because of this government’s policies. It is not appropriate to attempt to compare those peoples’ experiences with some larger group who have not died or have not yet experienced those harms. Where is the empirical evidence of these claims, anyway? Where is the DWP’s study report?

Callousness and indifference to the suffering and needs of disadvantaged citizens – disadvantaged because of discriminatory policies – has become so normalised to this government that they no longer see or care how utterly repugnant and dangerous it is.

The DWP are not ‘providing’ anything. Social security is a publicly funded safety net, paid for by the public FOR the public. It’s a reasonable expectation that citizens, most of who have worked and contributed towards welfare provision, should be able to access a system of support when they experience difficulties – that is what social security was designed to provide, so that no one in the UK need to face absolute poverty. It’s supposed to be there so that everyone can meet their basic survival needs.

What people in their time of need find instead is a system that has been redesigned to administer punishments, shame and psychological abuse. What kind of government kicks people hard when they are already down?

Universal Credit was considered the antidote for the Conservative’s ‘welfare dependency’ myth, yet there has never been any empirical evidence to support their claims of the existence of a ‘culture of dependency’ and that’s despite the dogged research conducted by Keith Joseph some years ago, when he made similar claims. He never found any evidence despite trying very hard. Most people move in and out of work, because jobs have become increasingly precarious over the last few years.

In fact over recent years, an international study of social safety nets from The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard economists categorically refutes the Conservative ‘scrounger’ stereotype and dependency rhetoric. Gabriel Kreindler, Benjamin Olken and colleagues re-analyzed data from seven randomized experiments evaluating cash programs in poor countries and found “no systematic evidence that cash transfer programmes discourage work.”

The phrase ‘welfare dependency’ diverts us from political class discrimination via policies, increasing inequality, and it serves to disperse public sympathies towards the poorest citizens, normalising the inequality and prejudice embedded in neoliberal ideology and resetting social norm defaults that then permit the state to target protected social groups for further punitive and cost-cutting interventions to ‘incentivise’ them towards ‘behavioural change.’ Outrageously, the behavioural change required by the state is that the public do not use publicly funded welfare services.

Stepping back from this, it becomes clear that the policy driver is ‘small state’, antiwelfarist neoliberal ideology. This is being propped up by pseudoscientific behavioural economic rationalisations.

There is mounting evidence, according to local authority researchers in Liverpool, for example, that shows the actual effect is the reverse of what was claimed was intended; Universal Credit is harming the very people it was designed to support. It is forcing households into debt, causing severe poverty including to those in work, leaving too many people, including children, facing food insecurity, destitution and eviction. Liverpool council’s welfare reform cumulative impact analysis last year shows that the groups most adversely affected by the Government’s raft of ‘welfare reforms’ are the long-term sick and disabled, families with children, women, young adults and the 40-59 age group who live in social housing.

Many working households are suffering a shortfall in Housing Benefit, Housing Allowance and a reduction and removal of many other benefits, all set against the backdrop of ever increasing living costs. Poverty disincentives people.

In recent years welfare conditionality has become conflated with severe financial penalities (sanctions), and has mutated into an ever more stringent, complex, demanding set of often arbitrary requirements, involving frequent and rigid jobcentre appointments, meeting job application targets, providing evidence of job searches and mandatory participation in workfare schemes. The emphasis of welfare provision has shifted from providing support for people seeking employment to increasing conditionality of conduct, enforcing particular patterns of behaviour and monitoring citizen compliance.

Government Statistics tell us that more people get sanctioned under Universal Credit than under the existing legacy benefits system.

Sanctions are “penalties that reduce or terminate welfare payments in cases where claimants are deemed to be out of compliance with requirements.” They are, in many respects, the neoliberal-paternalist tool of discipline par excellence – the threat that puts a big stick behind coercive welfare programme rules and “incentivises” citizen compliance with a heavily monitoring and supervisory administration. The Conservatives have broadened the scope of behaviours that are subject to sanction, and have widened the application to include previously protected social groups, such as sick and disabled people and lone parents.

There is plenty of evidence that sanctions don’t help people to find work, and that the punitive application of severe financial penalities is having a detrimental and sometimes catastrophic impact on people’s lives. We can see from a growing body of research how sanctions are not working in the way the government claim they intended.

Sanctions, under which people lose benefit payments for between four weeks and three years for “non-compliance”, have come under fire for being unfair, punitive, failing to increase job prospects, and causing hunger, debt and ill-health among jobseekers. And sometimes, even causing death.

However, if people are already needing to claim financial assistance which was designed to meet only very basic needs, such as provision for food, fuel and shelter, then imposing further financial penalities will simply reduce those people to a struggle for basic survival, which will inevitably demotivate them and stifle their potential.

The current government demand an empirical rigour from those presenting criticism of their policy, yet they curiously fail in meeting the same exacting standards that they demand of others. Often, the claim that “no causal link has been established” is used as a way of ensuring that established correlative relationships, (which often do imply causality,) are not investigated further.

Qualitative evidence – case studies, for example – is very often rather undemocratically dismissed as ‘anecdotal,’ or as ‘scaremongering’ which of course stifles further opportunities for research and inquiry.

The Conservative shift in emphasis from structural to psychological explanations of poverty has far-reaching consequences. The partisan reconceptualision of poverty makes it much harder to define and very difficult to measure. Such a conceptual change disconnects poverty from more than a century of detailed empirical and theoretical research, and we are witnessing an increasingly experimental approach to policy-making, aimed at changing the behaviour of individuals, without their consent.

This approach isolates citizens from the broader structural political, economic, sociocultural and reciprocal contexts that invariably influence and shape an individuals’s experiences, meanings, motivations, behaviours and attitudes, causing a problematic duality between context and cognition. It places unfair and unreasonable responsibility on citizens for circumstances which lie outside of their control, such as the socioeconomic consequences of political decision-making.

I want to discuss two further considerations to add to the growing criticism of the extended use of sanctioning, which are related to why sanctions don’t work. One is that imposing such severe financial penalities on people who need social security support to meet their basic needs cannot possibly bring about positive “behaviour change” or incentivise people to find employment, as claimed. This is because of the evidenced and documented broad-ranging negative impacts of financial insecurity and deprivation – particularly food poverty – on human physical health, motivation, behaviour and mental states.

The second related consideration is that “behavioural theories” on which the government rests the case for extending and increasing benefit sanctions are simply inadequate and flawed, having been imported from a limited behavioural economics model (otherwise known as nudge” and libertarian paternalism) which is itself ideologically premised.

Sanctions and workfare arose from and were justified by nudge theory, which is now institutionalised and deeply embedded in Conservative policy-making. Sanctions entail the manipulation of a specific theoretical cognitive bias called loss aversion.

At best, the new “behavioural theories” are merely theoretical propositions, at a broadly experimental stage, and therefore profoundly limited in terms of scope and academic rigour, as a mechanism of explanation, and in terms of capacity for generating comprehensive, coherent accounts and understanding about human motivation and behaviour.

I reviewed research and explored existing empirical evidence regarding the negative impacts of food poverty on physical health, motivation and mental health. In particular, I focussed on the Minnesota Semistarvation Experiment and linked the study findings with Abraham Maslow’s central idea about cognitive priority, which is embedded in the iconic hierarchy of needs pyramid. Maslow’s central proposition is verified by empirical evidence from the Minnesota Experiment.

The Minnesota Experiment explored the physical impacts of hunger in depth, but also studied the effects on attitude, cognitive and social functioning and the behaviour patterns of those who have experienced semistarvation. The experiment highlighted a marked loss of ambition, self-discipline, motivation and willpower amongst the subjects once food deprivation commenced. There was a marked flattening of affect, and in the absence of other emotions, Doctor Ancel Keys observed the resignation and submission that continual hunger manifests.

The understanding that food deprivation dramatically alters emotions, motivation, personality and that nutrition directly and predictably affects the mind as well as the body is one of the legacies of the experiment.

The experiment highlighted very clearly that there’s a striking sense of immediacy and fixation that arises when there are barriers to fulfiling basic physical needs – human motivation is frozen to meet survival needs, which take precedence over all other needs. This is observed and reflected in both the researcher’s and the subject’s accounts throughout the study. If a person is starving, the desire to obtain food will trump all other goals and dominate the person’s thought processes.

In a nutshell, this means that if people can’t meet their basic survival needs, it is extremely unlikely that they will have either the capability or motivation to meet higher level psychosocial needs, including social obligations and responsibilities to seek work. Abraham Maslow’s humanist account of motivation also highlights the same connection between fundamental motives and immediate situational threats.

Ancel Keys published a full report about the experiment in 1950. It was a substantial two-volume work titled The Biology of Human Starvation. To this day, it remains the most comprehensive scientific examination of the physical and psychological effects of hunger.

Keys emphasised the dramatic effect that semistarvation has on motivation, mental attitude and personality, and he concluded that democracy and nation building would not be possible in a population that did not have access to sufficient food.

I also explored the link between deprivation and an increased risk of mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, depression, anxiety and substance addiction. Poverty can act as both a causal factor (e.g. stress resulting from poverty triggering depression) and a consequence of mental illness (e.g. schizophrenic symptoms leading to decreased socioeconomic status and prospects).

Poverty is a significant risk factor in a wide range of psychological illnesses. Researchers recently reviewed evidence for the effects of socioeconomic status on three categories: schizophrenia, mood and anxiety disorders and substance abuse. Whilst not a comprehensive list of conditions associated with poverty, the issues raised in these three areas can be generalised, and have clear relevance for policy-makers.

The researchers concluded: “Fundamentally, poverty is an economic issue, not a psychological one. Understanding the psychological processes associated with poverty can improve the efficacy of economically focused reform, but is not a panacea. The proposals suggested here would supplement a focused economic strategy aimed at reducing poverty.” (Source: A review of psychological research into the causes and consequences of poverty – Ben Fell, Miles Hewstone, 2015.)

There is no evidence that keeping benefits at below subsistence level or imposing punitive sanctions ‘incentivises’ people to work and research indicates it is likely to have the opposite effect.

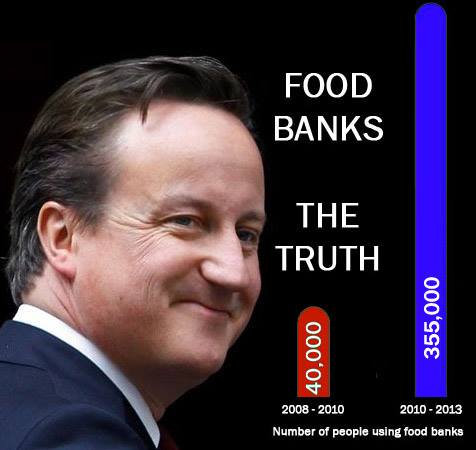

Food banks have reported that demand for charity food goes up significantly when Universal Credit is introduced into the local area.

The Trussell Trust has expressed concern that, given the links between Universal Credit, financial hardship, and foodbank use, the next stage of the roll out could lead to further increased financial need and more demand for foodbanks. Their report uses referral data from Trussell Trust foodbank vouchers to examine the impact of Universal Credit on foodbank use. Their key findings were:

- On average, 12 months after rollout, foodbanks see at least a 52% increase in demand, compared to 13% in areas with Universal Credit for 3 months or less. This increase cannot be attributed to randomness and exists even after accounting for seasonal and other variations.

- Benefit transitions, most likely due to people moving onto Universal Credit, are increasingly accounting for more referrals and are likely driving up need in areas of full Universal Credit rollout. Waiting for the first payment is a key cause, while for many, simply the act of moving over to a new system is causing serious hardship.

The Trussell Trust says that poor administration, the long wait for the first payment, and repayments for loans and debts are driving some people into severe financial need. This is particularly acute for families with dependent children and disabled people.

Ministers still claim that evidence from early official trials shows people claiming Universal Credit were more likely to get a job. However, the Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) has said there remains insufficient evidence for this claim. Other researchers have found that the low benefit amounts coupled with rigid conditionality and sanctions profoundly disincentivise people to find work or progress in work. Evidence supports the latter proposition.

But the government simply responds by labelling researchers and campaigners as ‘scaremongers’ and continues to deny the well-evidenced and documented experiences of citizens which demonstrate that Universal Credit is harmful, creating distress and entrenching inequality and absolute poverty.

I don’t make any money from my work. But if you like, you can help me by making a donation to help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.