Tomorrow is cancelled

Tomorrow is cancelled

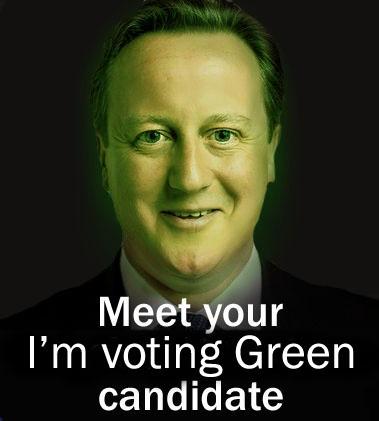

Cameron has announced that he will not seek a third term of office as Prime Minister. He named three of his senior colleagues – Home Secretary Theresa May, Chancellor George Osborne and London mayor Boris Johnson – as possible replacements for the conservative leadership when he stands down. It doesn’t matter who leads the Tory party: they all share the same despotic tendency.

I’ve often thought that Conservatism is an enclave for those with socially destructive dark triad personality traits (Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy). Tories share the same regressive social Darwinist ideology, so they will always tend to formulate the same policies that divide society into steep hierarchies of wealth and privilege, resulting in massive inequalities, suffering and poverty, lies, corruption and indifference to the majority of the publics’ needs. No matter who is in the driving seat of the Tory tank, it will still knock most of us down and drive over us.

Cameron’s soundbites, such as “we are all in it together” and concepts like “the Big Society” hark back to a traditional paternalist Conservatism that had an element of communitarianism to offer. But without a “big state.” One nation Conservatives are often seen as being less harsh and a tad more “cuddly” than New Right Conservatives. Whilst one nation Conservatism is sometimes hailed as “progressive,” (but only ever amongst Conservatives,) that is tempered by the fact that all tories tend to hold onto a misty-eyed illusion of some great Victorian golden-age and the Feudal era “good ole’ days.” They never look forwards, only backwards.

It was the dominance of so-called “Red Toryism” that facilitated the post-war consensus which saw the welfare state embraced by the major parties in the 1940s. However, most Conservatives, including the new so-called Red Tories, claim that the post-war expansion of the state led to a “breakdown of once-strong communities.” Not only is this claim immensely counter-intuitive, it’s utter pseudo-nostalgic nonsense.

Cameron’s rhetoric is full of references to “rolling back the state”, the “re-awakening of community spirit”, and a restoration of the kind of “intermediate civic institutions” that preceded the welfare state. The whole idea of Cameron’s “big society” is that private charities fill the holes created by public spending cuts. Food banks have increasingly replaced welfare, for example, yet the point of post-1945 European welfare states was to free the needy from dependence on the insecurity of private generosity, which tends to miss out the socially marginalised, and to be least available when times are hardest.

Welfare, or social security, if you prefer, has provided a sense of security and dignity that we never previously enjoyed, it established a norm of decency, mutuality of our social obligations and created a parity of esteem and worth which was, until fairly recently, universal, regardless of wealth and status. The “big bad state” is comprised of civilised and civilising institutions. It is such stable and enduring institutions and subsequently secure individuals that are raised above a struggle for basic survival which provide a frame for coherent communities. The Conservatives, with their demagoguery of rigid class division, and policies of social stratification, tend to create ghettoes, not communities.

Traditional Conservatives were very influenced by Malthus, and opposed every form of social insurance “root and branch”, arguing, as the economist Brad DeLong put it:

“Make the poor richer, and they would become more fertile. As a result, farm sizes would drop (as land was divided among ever more children), labor productivity would fall, and the poor would become even poorer. Social insurance was not just pointless; it was counterproductive.”

Malthus was a miserable, misanthropic clergyman for whom birth control was anathema. He believed that poor people needed to learn the hard way to practice frugality, self-control, and chastity. He liked to hand out allegoric and austere hair shirts and birch rods for the poor. The traditional Conservatives also protested that the effect of social insurance would be to weaken private charity and loosen traditional social bonds of family, friends, religious, and non-governmental welfare organisations.

The moralising scrutiny, control and punishment of the poor is a quintessential element of Tory narrative. Tory ideology never changes. They refuse the lessons of history, and reject the need for coherence. Tories really are stuck in the Feudal era. They have never liked the idea of something for everyone:

“The crisis is an opportunity to sweep away the rotten postwar settlement of British politics. Labour is moribund. But David Cameron has a chance to develop a “red Tory” communitarianism, socially conservative but sceptical of neoliberal economics.” Phillip Blond, The Rise of the Red Tories, 2009.

The Telegraph identified Blond as a key “driving force behind Cameron’s Big Society agenda.” There are possibly two kinds of Tory. But both types will always engineer two nations: fundamentally demarcated by wealth and privilege: one nation of haves and another of have nots.

Conservatives also believe they have moral superiority, and they always impose a framework of moral authoritarianism on the poorest. For example, Cameron’s idea of “social responsibility” does not extend to the behaviours of irresponsible bankers, the finacial class and the tax-avoidant wealthy. It’s not just a cognitive dissonance amongst Conservatives – many in the UK fail to recognise the direct relationship between high salaries and a concentration of wealth at the top of society, and low salaries paid to the poor, and poverty at the bottom: there you have it – two nations.

The paternalism of traditional Tories and the authoritarianism of the New Right are profoundly undemocratic: neither design can reflect the needs of the public since both frameworks are imposed on a population, reflecting only the needs of the ruling class, to preserve social order.

Solidarity was said to be the movement that turned the direction of history. But we have turned away from it. Émile Durkheim, one of the three founding fathers of theoretical sociology, first developed the concept of social exclusion to describe the manifold consequences of poverty and inequality.

Much of Durkheim’s work was concerned with how societies could maintain their integrity, order and coherence. Durkheim’s answer is that our collective consciousness produces society and holds it together. His view that societies evolve through a stage of mechanistic solidarity to progress to a state of organic solidarity betrays his traditional conservative roots. But Tory notions of solidarity are not based on any belief in the value of cooperation, community, collectivism or altruism: Tories don’t feel any connection with ordinary people. It’s entirely a detached and pragmatic consideration: for Tories, social solidarity serves the sole purpose of maintaining the status quo. Preserving the two nations.

Disraeli’s Conservatism favoured a paternalistic society with the hierarchical social classes maintained but with the working class receiving support from the establishment. He emphasised the importance of social obligation rather than individualism. Disraeli warned that Britain would become divided into two “nations”, of the rich and poor, as a result of increased industrialisation and inequality. Concerned at this stark division, he supported measures to improve the lives of the people, to provide social support and protect the working classes.

One nation Conservatism originally emphasised the obligation of those at the top to those below. This was based on the Feudal concept of noblesse oblige – the belief that the aristocracy had an obligation to be generous and honourable. Disraeli felt that governments should be paternalistic, because it is “good” for society as a whole, to maintain social order. So his ultimate motivation was to simply prop up the established status quo.

Disraeli became Conservative prime minister in February 1868. He devised one nation policy to appeal to working class men as a solution to worsening divisions in society. But conservatives always conclude that the preservation of social hierarchy is in the interests of all classes, and therefore all classes should collaborate in its defense.

Both the lower and the higher classes should accept their roles and perform their respective duties.

The rich man at his castle, the poor man at his gate.

The stability and the prosperity of the nation was seen as the ultimate purpose of collaboration between classes.

Traditional Conservatives believed that organic societies are fashioned ultimately by natural necessity, and therefore cannot be improved by reform or revolution. Indeed, reform or revolution would destroy the delicate fabric of society, creating the possibility of radical social breakdown, from this perspective.

Disraeli once said: “If the cottages are happy, the castle is safe.” Characteristically pragmatic and relatively paternalistic, then.

One nation Conservatives such as R. Butler, I. Macleod, H. Macmillan and Q. Hogg, who harked back to the Disraeli pragmatist tradition, were prepared to accept the expansion of state activity ushered in via by the 1945-51 Labour government programmes, involving selective nationalisation, expansion of the welfare state, Keynesian economic policies and tripartite decision-making.

Though the Tories continued to place emphasis on the most profitable sectors of the economy, which would remain in private control and they still supported the perpetuation of economic inequality because of their belief that private property was a prerequisite for liberty and that capitalist economic inequality could best promote wider economic growth and rising living standards. However, in fairness, one nation Conservatives also recognised that full employment and the expansion of the welfare state were necessary to improve health, housing, education and to reduce poverty if the UK was to be cohesive.

Thatcher’s New Right neoliberalism was quite a radical break from Tory tradition and it embodied a regressive, mechanistic, individualistic theory of society. She said: “There’s no such thing as society; only individuals and families.”

Traditional Conservatives had a deep mistrust of human rationality and reason and a deep dislike of the abstract, certainly since Edmund Burke. In contrast, the New Right’s neoliberalism heralded a new image of “human nature,” which was very much based on the imported philosophy of Ayn Rand: we are rational and entirely self-seeking, in the context of negative economic freedom (free from state intervention, in theory, a least), within the free market. Rand rejected altruism and opposed collectivism.

Rand was a major inspiration for the American Tea Party movement, which has swept a new generation of Republicans and self-described Conservatives into power in the USA. The Randian neoliberalist economic context has also framed a political, social and moral authoritarianism, disciplinarianism and illiberality that has replaced traditional paternalism, and in this respect, the New Right pioneered a strongly anti-democratic, over-controlling state.

The ideological roots of the New Right also lie partly in the liberal free market economy that dominated the Victorian era, (and liberalism has always been about individualism), along with a strong belief in social hierarchy based on a natural order. However, laissez faire was a form of industrial capitalism. Neoliberalism is a newer form of financial capitalism. As an ideology it is totalising, because it’s also about literalising the market metaphor; thinking all interacations as governed by a rationale like that of markets.

New Right Conservatism weds meritocratic principles to the strong class divide tradition, though it’s an insincere partnership. References to meritocracy are usually used to bolster the claim by the wealthy and powerful that their wealth is deserved. Of course, by inference, poverty is also deserved. Yet we had certainly learned by the 1940s that it is social policies that create inequality and poverty.

Cameron claims Disraeli’s one nation Conservatism as a mantle. However, he has much more in common with Thatcher. Disraeli’s notion of a “benevolent hierarchy” bears little resemblance to the New Right’s persistent attacks on the dependency or entitlement culture deemed to have been created by the welfare state.

And one nation Conservatives would not privatise our public services, NHS and dismantle welfare. Nor would they endorse such unrestained neoliberalism.

The New Right is rather more about noblesse disoblige.

One nation Tories would recognise that the welfare state is a necessity that arose to protect citizens against the worst ravages of unfettered capitalism. It’s really the very least they can do to preserve social order. Inequality didn’t change as a consequence of welfare, but at least poverty was relativised, until recently.

Cameron’s policies of anti-welfarism have resulted in the return of absolute poverty. There’s a certain irony in the Tory preoccupation with preserving social order: their rigid ideologically-driven policies create the very things they fear – dissent, insecurity, disorder, and the recognition of a need for social change and reform. It’s always the case that Tory governments prompt a growth of radicalism and revolutionary ideas. That happens when people are stifled and oppressed.

Social Security policy resulted in the development of what was considered to be a state responsibility towards its citizens. Welfare is a social protection that is necessary. There was also an embedded doctrine of fostering equity in these policies, although that doctrine arose from within the Labour Party, of course.

As I have said elsewhere, New Right rhetoric is designed to have us believe there would be no poor if the welfare state didn’t “create” them. If the Conservatives must insist on peddling the myth of meritocracy, then surely they must also concede that whilst such a system has some beneficiaries, it also creates situations of insolvency and poverty for others.

This wide recognition that the raw “market forces” of laissez-faire and stark neoliberalism causes casualties is why the welfare state came into being, after all – because when we allow such competitive economic dogmas to manifest, there are invariably “winners and losers”. That is the nature of competitive individualism, and along with inequality, it’s an implicit, undeniable and fundamental part of the meritocracy script. And that’s before we consider the fact that whenever there is a Conservative-led government, there is no such thing as a “free market”: in reality, all markets are rigged for elites.

New Right Conservatism has blended classical liberalism, with its roots in competitive individualism and with ideas of a status-based social order. In contrast, democratic socialism has its foundation in solidarity. The former framework atomises society, breaking our sense of common bonds, pitching us against each other to compete for resources, fracturing our narrative of collective, common experience: it is about social exclusion. The latter framework unites us in cooperation, mutuality, mutual aid and reciprocity of perspective: it is about social inclusion.

I’ve said elsewhere that the Conservatives are creatures of habit rather than reason. Traditionalists, always. That is the why their policies are so stifling and anti-progressive for the majority of us. It’s why Tory policies don’t meet public needs. We always witness the social proliferation of fascist ideals with a Tory government, too. It stems from the finger-pointing divide and rule mantra: it’s them not us, them not us. But history refutes as much as it verifies, and we learned that it’s been the Tories all along. With a Conservative government, we are always fighting something. Poverty, social injustice: we fight for political recognition of our fundamental rights, which the Tories always circumvent. We fight despair and material hardship, caused by the rising cost of living, low wages, high unemployment and recession that is characteristic of every Tory government.

I think people often mistranslate what that something is. Because Tory rhetoric is all about othering: dividing, atomising of society into bite-sized manageable pieces by amplifying a narrative of sneaking suspicion and hate thy neighbour via the media.

The Tories foster incoherence and division. The world stopped making sense in 2010. The Tory-led government don’t even pretend to be rational policy-makers. Our foundations and our grounding are being knocked away. Everything becomes relative and fleeting. Transient and precarious.

Except for the rich and powerful: they still have their absolutes. We ordinary people are left just coping with crumbling logic, crumbling lives and a crumbling sense of what is real.

It strikes me that whilst we appear to have enclaves of consensus – and the media help perpetuate that impression – when you step back from that, you begin to see how divisive that apparent group consensus actually is, paradoxically. It’s really a form of bystander apathy.

We have in groups/out groups. We divide and make people into “others.” Each group fighting for something in a manufactured context of “scare resources”, the rising cost of living, sometimes against each other, but with no combined effort and genuine cooperation amongst us, that leaves each individual group wishing in the wind.

Now is the time for people to work together and value cooperation, joint efforts and pooled resources. People’s identities only make sense in the context of society, anyway. The Tories are historically unempathically, unremorsefully and irresponsibly wrong. We are social and interdependent, inter-relating creatures. Social hierarchies damage our bonds.

The barbarians are not outside the gates: they are inside the castle governing us, inflicting irremediable economic deprivation, extending inequalities and divisions of wealth and income, organising our society into competing and antagonistic interests.

Two nations.