“This is a round up.”

The song is about a world where citizens are deeply suspicious of one another, where fear of the Other is politically instigated and nurtured, social conformity, discrimination, exclusion and prejudice reign supreme. It’s about a society blindly climbing Allport’s ladder.

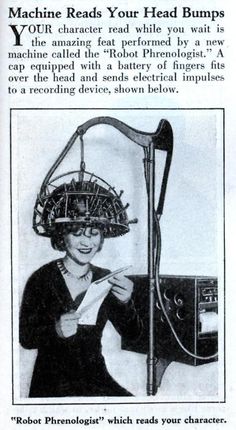

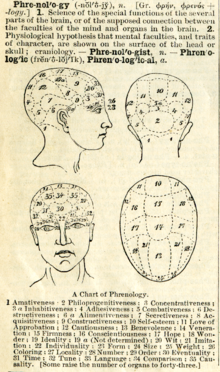

“Of the forehead, when the forehead is perfectly perpendicular, from the hair to the eyebrows, it denotes an utter deficiency of understanding.” Johann Kaspar Lavater, phrenologist (1741–1801).

Back in the nineteenth century, phrenology was the preferred “science” of personality and character divination. The growth in popularity of “scientific” lectures as entertainment also helped spread phrenology to the masses. It was very popular among the middle and working classes, not least because of its simplified principles and wide range of social applications that were supportive of the liberal laissez faire individualism inherent in the dominant Victorian world view. It justified the status quo. Even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert invited the charlatan George Combe to feel the bumps and “read” the heads of their children.

During the early 20th century, there was a revival of interest in phrenology, partly because of studies of evolution, criminology and anthropology (pursued by Cesare Lombroso). Some people with political causes used phrenology as a justification narrative for European superiority over other “lesser” races. By comparing skulls of different ethnic groups it supposedly allowed for ranking of races from least to most evolved.

It’s now largely regarded as an obsolete and curious amalgamation of primitive neuroanatomy, colonialist supremicism with a dash of moral philosophy. However, during the 1930s Belgian colonial authorities in Rwanda used phrenology to explain the so-called superiority of Tutsis over Hutus. More recently in 2007, the US State of Michigan included phrenology (and palm reading) in a list of personal services subject to sales tax.

Any system of belief that rests on the classification of physical characteristics is almost always used to justify prejudices, social stratifying and the ranking of human worth. It highlights what we are at the expense of the more important who we are. It profoundly dehumanises and alienates us.

Though the saying “you need your bumps feeling” has lived on, may the pseudoscience of phrenology rest in pieces.

Phrenology is dead: long live the new moralising pseudoscience

The Conservatives have simplified the art of personality and character divination. They have set up a new economic department of the mind called the Behavioural Insights Unit. This fits with the age old Conservative motif of a “broken Britain”and their obsessive fear of social “decay and disorder.” Apparently, we are always on the point of moral collapse, as a society. And apparently, it isn’t the government’s decision-making that is problematic: poor people are entirely responsible for the poor state of our country. Those who have the very least are to blame. That’s why they need such targeted austerity policies, to ensure they have even less. We can’t have the poor being rewarded with not being poor, that’s just bad for big business.

Under every Conservative government, we suddenly see the proliferation of bad sorts; cognitively biased and morally incompetent people making the wrong choices everywhere and generally being inept, non-resilient and deficient characters. The way to diagnose these problems of character, according to the government, is to establish whether or not someone is “hard working”. This is usually determined by the casting of chicken bones, and a quick look at someone’s bank balance. If it lies offshore, you are generally considered a jolly good sort.

If you need to claim social security, be it in-work or out-of-work support, then you are most definitely a “wrong sort”; a faulty person and therefore in need of some state treatment to put you right, just to ensure that your behaviours are optimal and aligned with politically defined neoliberal outcomes. Apparently, poor people are the new “criminal types.” The only cure, according to the government, is to make poor people even poorer, by a variety of methods, including a thorough, coercive nudging: a “remedial” income sanctioning and increased conditionality to eligibility for support; benefit cuts; increasing welfare caps and a systematic dismantling of the welfare state more generally,

Oh, and regular shaming, outgrouping, stigmatising and scapegoating in the meanstream media and political rhetoric, designed to create folk devils and moral panic.

The new benefit cap: a policy designed by the neoliberal rune casters

The regressive benefit cap will save a paltry amount of money in the short term. In the long term it will cost our health and social services many millions. It’s misleading of the government to claim that it will save the “tax payers” money, since most people needing to claim social security have worked and paid taxes too. VAT is also a tax, and last time I checked, people needing support because they lost their job or became sick or injured are not exempt from paying taxes. In fact the poorest families pay the highest proportion of their income in tax.

We forget that people in poverty pay taxes because we forget how many different ways we are taxed:

- VAT

- Duties

- Income tax

- National Insurance

- Council tax

- Licences

- Social care charges, and many others taxes

- Bedroom tax

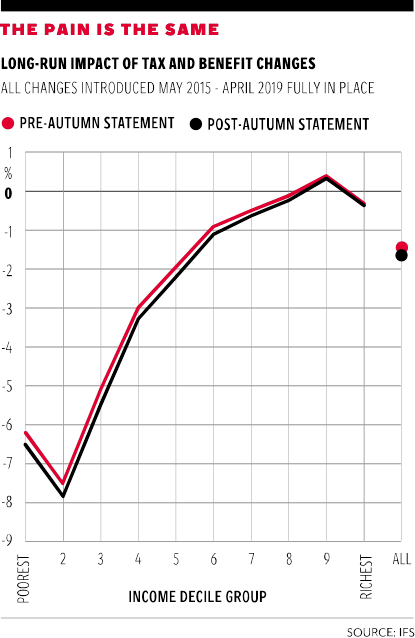

Of course there’s a stark contrast in the way the state coerces the poorest citizens into behaving “responsibly”, carrying the full burden of austerity, while there is an abject failure to rein in executive pay, or to tax the Conservative party paymasters, and recover the billions lost in revenue to the Treasury through tax havens.

Poor people get the bargain basement package of behavioural incentives – which is all stick and no carrots – whereas the wealthy get the deluxe kit, with no stick and plenty of financial rewards.

Nearly a quarter of a million children from poor families will be hit by the extended household benefit cap due to be introduced this autumn, according to the government’s latest analysis of the impact of the policy. It will see an average of £60 a week taken out of the incomes of affected households that are already poor, pushing them even deeper into poverty. About 61% of those affected will be female lone parents.

The cap will damage the life chances of hundreds of thousands of children, and force already poor families to drastically cut back on the amount they spend on essential items to meet basic needs, such as food, fuel and clothing. Originally benefit rates were calculated to meet basic survival needs – covering the costs of food, fuel and shelter only.

The new cap unjustifiably restricts the total amount an individual household can receive in benefits to £23,000 a year in London (£442 a week) and £20,000 in the rest of the UK (£385 a week). It replaces the existing cap level of £26,000. All of this support is dependent on whether or not you comply with the very complex conditionality criteria. The support can be withdrawn suddenly, in the form of a sanction, for any number of reasons, and quite often, because your benefit advisor simply has targets to reach in order to let you know that nothing at all may be taken for granted: eating, feeding your children, sleeping indoors and keeping warm in particular.

The government claims the cap incentivises people to search for work, and says that 23,000 affected households have taken a job since the introduction of the first cap in 2013. However, the government uses “off flow” as a measurement of employment, which is unreliable, as studies have indicated many claimants simply vanish from record.

Worryingly, an audit in January this year found that the whereabouts of 1.5 million people leaving the welfare records each year is “a mystery.” The authors also raise concern that the wellbeing of at least a third of those who have been sanctioned “is anybody’s guess.” It’s not the first time these concerns have been raised.

It emerged in 2014, during an inquiry which was instigated by the parliamentary Work and Pensions Select Committee, that research conducted by Professor David Stuckler shows more than 500,000 Job Seekers Allowance (JSA) claimants have disappeared from unemployment statistics, without finding work, since the sanctions regime was toughened in October, 2012.

This means that in August 2014, the claimant count – which is used to gauge unemployment – is likely to be very much higher than the 970,000 figure that the government is claiming, if those who have been sanctioned are included.

A Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) spokesman said: “The benefit cap restored fairness to the system by ending the days of limitless benefit claims and provides a clear incentive to move into work.”

However, firstly, social security is based on a national insurance contribution principle, and was already fair. Most people have worked and contributed to their own provision. Secondly, people in work are also poor. Those on low pay who need to claim additional support are also being sanctioned for “non-compliance”. In fact much of our welfare spending goes towards supporting those people in work on low wages. We spend most on pensions, a large amount on in-work benefits and relatively little provision is for those out of work. The DWP don’t half chat some rubbish. A fair system would entail the government ensuring that employers pay adequate wages that cover rising living costs, instead of permitting employers to profit from our welfare state.

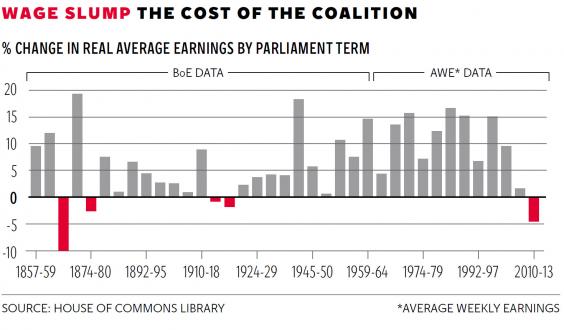

In a deregulated labour market, poorly paid workers are now held individually and entirely responsible for how much they earn, how many hours they work, and generally “progressing in work”. If they don’t “progress”, then what used to be an issue for trade unions and collective bargaining is now an issue addressed by punitive social security law, authoritarian welfare “advisors” and financial penalties.

You can see where the incremental increases in the benefit cap are leading the public. The justifications and line of reasoning presented by the Conservatives are leading us down a cul-de-sac of rationale, where the welfare state is completely dismantled, and the reason given will be that this ensures “everyone works”, regardless of labour market conditions and the availability of reasonable quality and secure jobs that pay enough to support people, meeting their basic needs sufficiently to lift them out of poverty.

If these measures are intended to force people into work, this government’s self-defeating, never-ending austerity policy is hardly the ideal economic climate for job creation and growth, and where are the affordable social homes for the growing ranks of low paid workers in precarious financial situations because of increasing job insecurity and zero hour contracts? The gig economy is a political fig leaf.

An official evaluation of the cap by the Institute for Fiscal Studies in 2014 found the “large majority” of capped claimants did not respond by moving into work, and a DWP-backed study in Oxford published in June found that cutting benefit entitlements made it less likely that unemployed people would get a job. Not that we didn’t already know this. If people cannot meet their basic needs, then they simply struggle to survive and cannot be “incentivised” to meet higher level psychosocial needs. The government need to read about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and the Minnesota starvation experiment. (See Welfare sanctions can’t possibly “incentivise” people to work .)

Joanna Kennedy, chief executive of the charity Z2K, said: “Our experience helping those affected by the original cap shows that many of those families will have to reduce even further the amount they spend on feeding and clothing their children, and heating their home to avoid falling into rent arrears and facing eviction and homelessness.”

As Patrick Butler points out in the Guardian, the government have already been ordered to exempt carers from the cap after a judge ruled last year that it unlawfully discriminated against disabled people by capping benefits for relatives who cared for them full time. Ministers had argued that carers who looked after family members for upwards of 35 hours a week should be treated as unemployed.

A previous court ruling found that the benefit cap breached the UK’s obligations on international children’s rights because the draconian cuts to household income it produced left families unable to meet their basic needs. This is the fifth wealthiest nation in the world, and supposedly a first world liberal democracy.

The deputy president of the supreme court, Lady Hale, said in her judgment: “Claimants affected by the cap will, by definition, not receive the sums of money which the state deems necessary for them adequately to house, feed, clothe and warm themselves and their children.”

As Stephen Preece from Welfare Weekly pointed out yesterday, the word vulnerable suggests that people are weak, when in fact they are only made vulnerable through the actions or inaction of those around them, including (and especially) the government. I agree. To label people as vulnerable displaces responsibility from government and diverts us from the reality and nature of the punitive policies aimed at poor citizens – this is political oppression.

Ideological justification narratives and pseudoscience

I waded through the government document Welfare Reform and Work Act: Impact Assessment for the benefit cap. Basically the government use inane nudge language and their central aim is to “incentivise behavioural change” throughout the assessment. But they then claim that they can’t predict or accurately measure that. It is very difficult to measure psychobabble accurately though, it has to be said.

There are a lot of techniques of neutralisation and euphemisms peppered throughout the document. For example, taking money away from the poorest citizens is variously described as: “achieving fairness for taxpayers” (as previously stated, people claiming benefits have usually worked: they have and continue to pay taxes); “ensures there is a reasonable safety net of support for the most vulnerable” (by cutting it away further).and “strengthening work incentives”.

For those alleged free riders claiming support because they fell on hard times, “doing the right thing” and “moving into work” is deemed to be the ultimate aim of the cap, regardless of whether or not the work is secure, appropriate, with adequate levels of pay to lift people out of poverty. Work, in other words, will set us free.

I also took the time and trouble to read the studies that the government cited as “evidence” to support their pseudoscientific claims. The government misquoted and misapplied the research they used, too. They made claims that were NOT substantiated by the scant research referenced. And there are many more studies that completely refute the outrageous and ideologically premised government claims made in this document.

For example, Freud makes the claims that: “Children in households where neither parent is in work are much more likely to have challenging behaviour at age 5 than children in households where both parents are in paid employment. Growing up in a workless household is associated with poorer academic attainment and a higher risk of being not in education, employment and training (NEET) in late adolescence.”

The study cited was Barnes, M. et al. (2012) Intergenerational Transmission of Worklessness: Evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study and Longitudinal Study of Young People in England. Department for Education research report 234. It says:

“Though it must be stated that much of the association between parental worklessness and these outcomes was attributable to these other risk factors facing workless families. Parental worklessness had no independent effect on a number of other outcomes, such as children’s wellbeing (not being happy at school, being bullied and bullying other children), feelings of lack of control, becoming a teen parent, and risky behaviour. This evidence provides limited support for a policy agenda targeted only at getting parents back into work. ”

It is poverty, not “worklessness” that creates poor social outcomes. That is why around half of the people queuing at food banks are those in work. The biggest proportion of welfare support paid out is in-work benefits.

Freud also states that: “A lower cap recognises that many hard working families earn less than median earnings – a lower cap provides a strong work incentive.”

Actually, raising wages in line with the cost of living would be a far better incentive, instead of punishing unemployed people for the failings of a Conservative government that always oversees an increasingly desperate reserve army of labour, and ever-falling wages.

Perhaps one of the most outrageous claims made in the document is that the cap is consistent with “UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.” Those sick and disabled people in the ESA work-related activity group are not protected from the cap. The government is currently being investigated by the UN for “gross and systematic” abuses of the human rights of disabled people, because of the previous welfare “reforms” (a euphemism for cuts).

This is an authoritarian government that is coercing people into any low paid and insecure work, regardless of how suitable it is. It’s about dismantling the welfare state, bit by bit. It is about ensuring people are desperate so that people’s right to turn down jobs that are unsuitable, thus reducing any kind of scope for collective bargaining to improve working conditions and pay, is removed. It’s also about bullying people into doing what the government wants then to do, removing autonomy and choices. That isn’t “incentivising”, it’s plain and brutal state coercion. All bullies and tyrants are behaviourists.

It’s impossible not to feel at least a degree of concern and outrage reading such incoherent, flimsy and glib rubbish from an ideologically-driven government waging a full on class war on the poorest citizens, and then claiming that is somehow “fair” to the “taxpayer”. And it’s noteworthy that there is a harking back to the discredited and prejudiced theories of Keith Joseph – “intergenerational worklessness” – which were debunked by the theorists’ OWN research back in the Thatcher era. It is being paraded as irrefutable fact once again.

I’m expecting a government phrenology unit to be established soon.

And an announcement that the Department for Work and Pensions is to be renamed the Malleus Maleficarum.

CONTRIBUTE TO POLITICS AND INSIGHTS