Yesterday I wrote an article about the government’s shameful lack of progress on disability rights in the UK. I discussed the details of a new report and the recommendations made by the UK Independent Mechanism update report to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

This is a summary of some key concerns that I only touched on in my original write up, and it also focuses on one of the important themes that emerged in the report: the potential impact of Brexit on disabled people’s rights.

The new report and submission to the UNCRPD – UK Independent Mechanism update report to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (published October 2018) – provides an independent assessment of the UK Independent Mechanism (UKIM) on the “disappointing” lack of progress by the UK governments to implement the UN’s recommendations since August 2017.

A year on, there is still no comprehensive UK-wide strategy demonstrating how the UK will implement the CRPD Committee’s recommendations. There has also been “continued reluctance” from the UK Government to accept the conclusions of the CRPD Committee’s inquiry report on the impact of the UK Government’s policies on the rights of disabled people.

Disabled people across the UK continue to face serious regression of their rights to an adequate standard of living and social protection, to live independently and to be included in the community. UKIM has reiterated that the grave and systematic violations identified by the CRPD Committee need to be addressed as a matter of urgency and that the overall approach of the UK Government towards social security protection requires a complete overhaul, so that it is informed by human rights frameworks, standards and principles, to ensure disabled people’s rights are respected, protected and fulfilled.

Despite the empirical evidence presented from a variety of researchers and the UN investigation concerning the significantly adverse effect of welfare reform on disabled people’s rights to independent living and to an adequate standard of living and social security, the UK Government has failed to act on this evidence and to implement the CRPD Committee’s recommendations regarding these rights.

The authors of the report remain seriously concerned about the continued failure of the UK Government to conduct an assessment of the cumulative impact on disabled people of multiple policy, cuts and law reforms in relation to living standards and social security.

In the section about prejudice and negative attitudes, the report also cites a shameful example of rhetoric from the government that has potentially reinforced negative attitudes and the stigma surrounding mental health and disability: “This includes the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hammond, stating before a Committee of the UK Parliament: ‘It is almost certainly the case that by increasing participation in the workforce, including far higher levels of participation by marginal groups and very high levels of engagement in the workforce, for example of disabled people – something we should be extremely proud of – may have had an impact on overall productivity measurements.’

Many people understood this statement as indicating that the increase in disabled people in employment is partly responsible for the UK’s decreasing productivity.”

The report also says that employment rates for disabled people have actually risen only very marginally.

Conservative prejudice is embedded in social security policy and administration

The UKIM report says that government has not taken appropriate measures to combat negative and discriminatory stereotypes or prejudice against persons with disabilities in public and the media, including the government’s own claims that ‘dependency’ on benefits is in itself a disincentive of employment. This is important because it shows just how embedded Conservative prejudice is in policies and within our social security administration.

The idea that welfare somehow creates the problems it was designed to alleviate, such as poverty and inequality, has become almost ‘common sense’ and because of that, it’s a narrative that remains largely unchallenged. Yet international research has shown that generous welfare provision leads to more, better quality and sustainable employment.

Moreover, this ideological position has been used politically as a justification to reduce social security provision so that it is no longer an adequate amount to meet citizens’ basic living needs. The aim is to discredit the welfare system itself, along with those needing its support. The government have long wished to replace the publicly funded social security provision ultimately with mandatory private insurance schemes.

The idea that welfare creates ‘dependency’ and ‘disincentivises’ work has been used as a justification for the introduction of cuts and an extremely punitive regime entailing ‘conditionality’ and sanctions. The governenment have selectively used punitive behavioural modification elements of behavioural economics theory and its discredited behaviourist language of ‘incentives’ to steadily withdraw publicly funded social security provision.

However, most of the public have already contributed to social security, those needing support tend to move in and out of work. Very few people remain out of work on a permanent basis. The Conservatives have created a corrosive and divisive myth that there are two discrete groups in society: tax payers and ‘scroungers’ – a class of economic free riders. This of course is not true, since people claiming welfare support also pay taxes, such as VAT and council tax, and most have already worked and will work again, given the opportunity to do so. For those who are too ill to work, as a so-called civilise society, we should not hesitate to support them.

In the recommendations, the authors say the government should implement broad mass media campaigns, in consultation with organisations representing persons with disabilities, particularly those affected by the welfare reform, to promote them as full rights holders, in accordance with the Convention; and adopt measures to address complaints of harassment and hate crime by persons with disabilities, promptly investigate those allegations, hold the perpetrators accountable and provide fair and appropriate compensation to victims.

As a society we take tend to take human rights for granted. We seldom think about rights because much of the time, there is no need to. It’s not until we directly experience discrimination and oppression that we recognise the value of having a universal human rights framework. Our rights define the relationship between citizen and state, and ensure that there is no abuse of power. However, we no longer have equal access to justice and redress for human rights breaches and discrimination.

The high demand for advice on disability benefits since the government’s welfare reform means that the almost complete removal of welfare benefits from the scope of legal aid has had a disproportionate impact on disabled people or those with a long-term health condition.

People entitled to disability benefits relied on legal aid to support appeals of incorrect decisions and to provide a valuable check on decision-making concerning eligibility for welfare support. The revisions to the financial eligibility criteria for legal aid have had a disproportionate impact on various groups including disabled people, women, children and migrants. This is because of the restrictions that the government placed on legal aid accessibility with the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO).

There has been a 99% decrease in support provided by the Legal Aid Agency for clients with disability-related welfare benefits issues, compared with pre-LASPO levels, and the total number of such claims has plummeted from 29,801 in 2011/12 to 308 in 2016/17.

The government has failed to ensure access to justice, removing appropriate legal advice and support, including through reasonable and procedural accommodation for disabled people seeking redress and reparation for the violation of their rights, as covered in the report.

It’s difficult to imagine that this wasn’t a coordinated effort on the part of the government to restrict citizen freedoms, support and access to justice for precisely those who need justice and remedies the most.

Human rights don’t often seem as though they matter, until they do. But by then, it may be too late.

Concerns about the impact of Brexit on the human rights of disabled people

In 2016, I wrote an article about concerns raised regarding the rights of disabled people following Brexit. Earlier this year, I wrote another article about my concerns that the European fundamental rights charter was excluded in the European Union (EU) withdrawal Bill, including protection from eugenic policy.

The result of the EU referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union, and forthcoming withdrawal, carries some obvious and very worrying implications for the protection of citizens rights and freedoms in the UK. Historically the UK Conservative government has strongly opposed much of Europe’s social rights agenda.

So it was very concerning that the House of Commons voted down a Labour amendment to ensure that our basic human rights are protected after Brexit, as set out in the European Union Charter.

The EU Withdrawal Bill threatened to significantly reduce existing human rights protections. It excluded both the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (in its entirety) and the right of action for violations of EU General Principles from domestic law after the UK’s withdrawal. It also handed sweeping powers to ministers to alter legislation without appropriate parliamentary scrutiny, placing current rights and equality laws at risk.

Worryingly, Suella Fernandes, who was promoted to the Brexit department earlier this year warned in November last year that transposing the ‘flabby’ charter into British law would give UK citizens additional protections on issues such as “biomedicine, eugenics, personal data and collective bargaining.”

However, the very fact that anyone at all in government objects to retaining these fundamental rights and protections indicates that we do very clearly need them.

It should be inconceivable that a democratic legislature would vote to take away citizens rights. The regressive step means the loss of the Charter goes rights that simply don’t exist in the Human Rights Act or in our common law. Gone is the enforceable right to human dignity. Gone are our rights to data protection, comprehensive protection for the rights of the child, a free-standing right to non-discrimination, protection of a child’s best interests and the right to human dignity, refugee rights, the right to conscientious objection, academic freedom and wide-ranging fair trial rights to name but a few. Then there are the losses of economic and social rights. Gone too, are the right to a private life, freedom of speech, equality provisions and employment rights governing how workers are treated. These are all laws that protect us all from abuses of power.

A group of more than 20 organisations and human rights legal experts, including the Equality and Human Rights Commission, signed an open letter on the importance of the Charter of Fundamental Rights ahead of the EU (Withdrawal) Bill returning to Parliament on 16 January this year. The letter was published in the Observer.

Trevor Tayleur, an associate professor at the University of Law, explained that the charter, although narrower in focus than the Human Rights Act, offers a far more robust defence of fundamental rights.

“At present, the main means of protecting human rights in the UK is the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) ,” he said. “This incorporates the bulk of the rights and freedoms enshrined in the European convention on human rights into UK law and thereby enables individuals to enforce their convention rights in the UK courts. However, there is a significant limitation to the protection afforded by the HRA because it does not override acts of parliament.

“In contrast, the protection afforded by the EU charter of fundamental rights is much stronger because where there is a conflict between basic rights contained in the charter and an act of the Westminster parliament, the charter will prevail over the act.”

Under the HRA, only an individual who is a “victim” of a rights violation can bring a claim, whereas anyone with “sufficient interest” can apply for judicial review based on the Charter (see this briefing at p 11)

In their report, UKIM say: “There are fears that the significant uncertainty in relation to Brexit will lead to a further deterioration of disabled people’s rights.

“The lack of a devolved government in Northern Ireland is also a specific concern to that jurisdiction, because it is significantly inhibiting the relevant departments from taking the required steps. Without a clear and coordinated plan for how the UK and devolved governments will address the UN recommendations systematically, the limited steps taken so far are unlikely to be enough to address the concerns raised by the CRPD Committee.”

The report goes on to say: “Following the European Union (EU) referendum in June 2016, there continues to be significant uncertainty regarding the future applicability of existing human rights protections in the UK that derive from EU law. The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights was excluded from the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, meaning that from ‘exit day’ it will no longer apply in domestic law.

“As a result, domestic protections are more vulnerable to repeal. The Charter goes further than the non-discrimination provisions in the Equality Act 2010 or the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Article 26 of the Charter, in particular, is a useful interpretive tool to support disabled people’s right to independence and integration and participation in the community.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 also leaves human rights protections at risk of being changed through the use of wide-ranging delegated powers. This means that changes to fundamental rights currently protected by EU law can be made by ministers through secondary legislation [statutory instruments, usually reserved for ‘non-controversial policy amendments] without being subject to full parliamentary scrutiny.

The EU is itself a party to the CRPD. Under EU law, international treaties to which the EU is party have a different status than they do under UK law. For example, EU law (unlike UK law) must be interpreted consistently with the CRPD. To ensure there is no regression, and that disabled people in the UK benefit from future progress driven by the CRPD, the UK Government should ensure these protections are incorporated into UK law, for example by giving enhanced status to the CRPD.

The Conservatives have used secondary legslation to try and quietly push through several very controversial policies over recent years, such as £4bn-worth of cuts to family tax credits, and the removal of maintenance grants from around half a million of the poorest students in England. The changes mainly hit disabled, ethnic minority and older students.

The government have introduced swathes of significant new laws covering everything from fracking to fox hunting and benefit cuts without debate and scrutiny on the floor of the House of Commons. Many of these policies were not included in the Conservatives’ election manifesto and were nodded through by obscure Commons committees without the substance of the change being debated.

After the House of Lords successfully challenged the tax credit instrument, the Government then proposed limiting peers rights to reject statutory instruments. This would mean if one was rejected by the Lords, the ministers would simply have to retable it and it would pass automatically. All of this should be seen alongside other Conservative proposals – including limits on freedom of information, changes to constituency boundaries and electoral registration, attempts to choke the opposition of funding within the Trade Union Bill, and the Lobbying Act.

In light of this repressive pattern of behaviour, you could be forgiven for thinking that we’ve entered the realms of constitutional gerrymandering, with an authoritarian executive waging war on the institutions that hold them to account. With its fear of opposition and loathing of challenge, the government wants to stifle debate, shut down opposition and block proper scruting and democratic accountability.

It is within this authoritarian political context that many of us have raised concerns about the impact of Brexit on the human rights of disabled citizens.

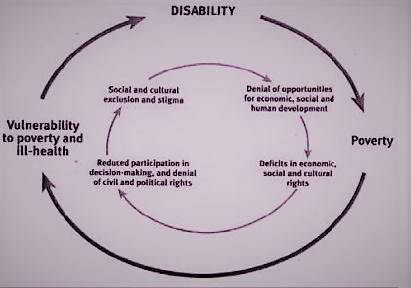

I’m always concerned that language use sometimes reinforces prejudices against disabled people by focusing on us as a group as ‘vulnerable’ and as ‘those in need’, as opposed to citizens and rights holders. However, grave and systematic violations of disabled peoples’ human right inevitably increases our vulnerability to further political abuse.

The Yogyakarta Principles, one of the international human rights instruments use the term “vulnerability” as such potential to abuse and/or social and economic exclusion. Social vulnerability is created through the interaction of social forces and multiple “stressors”, and resolved through social (as opposed to individual) means.

Social vulnerability is the product of social inequalities. It arises through social, cultural, political and economic processes.

While some individuals within a socially vulnerable context may break free from the hierarchical order, social vulnerability itself persists because of structural – social, cultural economical and political – influences that continue to reinforce vulnerability. Some campaigners are very critical of the use of the word ‘vulnerability’, because they feel it leads to attitudes and perceptions of disabled people as passive victims.

Since 2010, no social group has organised, campaigned and protested more than disabled people. Many of us have lived through harrowing times under this government and the last, when our very existence has become so precarious because of targeted and cruel Conservative policies and disproportionate cuts to our lifeline support. Yet we have remained strong.in our resolve. Despite this, some of our dear friends and comrades have been tragically lost – they have not survived, yet many of them were very strong in their resolve to challenge discrimination and oppression.

In one of the wealthiest democratic nations on earth, no group of people should have to fight for their survival. Vulnerability is rather more about the potential for some social groups being subjected to political abuse than it is about individual qualities. Disabled people currently are and have been. This is empirically verified by the report and conclusions drawn from the United Nations inquiry into the grave and systematic violations of disabled people’s human rights here in the UK, by a so-called democratic government.

The government’s ‘paternalism’ is authoritarian gaslighting

Over recent years, Conservative policies have become increasingly ‘paternalist’, also reflecting the authoritarian turn, in that they are designed to act upon us, to ‘change’ our behaviours through the use of negative reinforcement (‘incentives’), while we are completely excluded from policy design and aims. Our behaviours are being aligned with neoliberal outcomes, conflating our needs and interests with the private financial profit of the powerful.

As one of the instigators of the United Nations investigation, to which I regularly submitted evidence regarding the government’s systematic violations of the human rights of disabled people, and as a person with disability, I don’t care for being described by Damian Green as “patronising” or being told that disabled people – the witnesses of the investigation – presented an “outdated view” of disability in the UK. This is a government minister attempting to discredit and re-write our accounts and experiences while ignoring the empirical evidence we have presented. Such actions are profoundly oppressive.

The only opportunity disabled people have been presented with to effectively express our fears, experiences and concerns about increasingly punitive and discriminatory policies, to voice a democratic opinion more generally and to be heard, has been in dialogue with an international human rights organisation, and still this government refuse to hear what we have to say. Nor are we consulted with, democratically included or invited to participate in the executive’s decision-making that directly affects us. As UKIM note:

“There is a continued lack of action from the UK and devolved governments on the CRPD Committee’s recommendations. This includes setting up systems that will ensure that disabled people and their organisations are involved in the design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of legislation, policy or programmes that affect their lives. It remains unclear how the new Inter-Ministerial Group on Disability and Society will work with disabled people and their organisations, and UKIM, to promote and monitor implementation of UN CRPD.

“It is particularly concerning that the UN CRPD’s requirement to effectively involve disabled people and their organisations is not specifically reflected in the inter-ministerial group’s terms of reference. Nor do the terms of reference refer to the CRPD or the CRPD Committee’s recommendations.”

Oppression always involves the objectification of those being dominated; all forms of oppression imply the devaluation of the subjectivity and experiences of the oppressed.

This is very evident in the government’s approach to designing policies that act upon us. The government has consistently failed to actively consult, engage with and include disabled people, our representative organisations and give due consideration to our views in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of any legislation, policy or programme action related to our rights. Furthermore, the current Minister of State for Disabled People, Health and Work, Sarah Newton, has refused to meet with disabled people and allied organisations. (See also I’m a disabled person and Sarah Newton is an outrageous, gaslighting liar.)

Last year, Theresia Degener, who leads the UN’s Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), said the UK Government has “totally neglected” disabled people, during a two day meeting with UK government officials in Geneva.

Degener told them: “Evidence before us now and in our inquiry procedure as published in our 2016 report reveals that social cut policies have led to a human catastrophe in your country, totally neglecting the vulnerable situation people with disabilities find themselves in.”

The Government’s welfare cuts have resulted in “grave and systematic violations” of the rights of disabled people – a claim opposed by ministers but supported by UK courts.

For example, Judges have ruled that three of the government’s flagship welfare policies are illegal because of the impact they have on disabled people and single parents. In January 2016, the Court of Appeal declared the so-called ‘bedroom tax’ unlawful because of its consequences for disabled children, as well as victims of domestic violence.

Sanctions imposed on people who refused to or could not take part in the Department for Work and Pension’s ‘back to work’ schemes were also thrown out by Court of Appeal judges in April 2016. In June 2017 the High Court said the government’s benefit cap is unlawful and causes “real misery for no good purpose”. This year, a High Court ruling found that the Personal Independence Payments (PIP) policy had discriminated against people with mental health conditions.

Between 2011 and 2017 the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) underpaid more than £450,000,000 in means-tested benefits, due to its mishandling of the process by which claimants were moved from incapacity benefit to employment and support allowance.

When announcing its plans to remedy those underpayments on 14th December 2017, the DWP claimed the law ‘barred’ it from paying claimants any underpayments arising before 21st October 2014. That would have had two serious effects: first, up to £150,000,000 of the underpaid benefit would have been kept by the Government instead of passed to citizens who were deprived of it through no fault of their own; and second, any arrears which were paid to disabled people could after 52 weeks have been treated as ‘capital’, and reduced or stopped their ongoing entitlement to benefit.

In March 2018 the Child Poverty Action Group, acting for one affected claimant, brought judicial review proceedings in R (Smith) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions JR/1249/2018 arguing that the DWP’s position was unlawful. The DWP accepted that it ‘got the law wrong’. The DWP said it will now start making those payments. It was necessary to take legal action against the Government because it said it had no legal power to fully remedy the consequences of a major error it had made in transferring claimants from incapacity benefit to employment and support allowance.

Ministers have also accused by the UN of misleading the public about the impact of Government policies by refusing to answer questions and using statistics in an “unclear way.”

Gaslighting.

The CRPD Committee has requested that the State party (the government) disseminate the concluding observations of their inquiry widely, including to non-governmental organisations and organisations of persons with disabilities, and to disabled people themselves and members of their families, in national and minority languages, including sign language, and in accessible formats, including Easy Read, and to make them available on the government website on human rights.

That hasn’t happened and is unlikely to do so in the future. So please do share this article – The government’s shameful lack of progress on disability rights in the UK – new report update and submission to the UNCRPD Committee, and the UKIM update and shadow report widely.

I don’t make any money from my work. I’m disabled through illness and on a very low income. But you can make a donation to help me continue to research and write free, informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. I co-run a group online that helps people with ESA and PIP claim, assessment, mandatory review and appeal, increasingly providing one to one emotional support, too.

The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.