Theresa May’s new director of policy, John Godfrey, is a keen advocate of what he called, in his last job at financial services giant Legal and General, “Beveridge 2.0”: using technology to introduce new forms of “social insurance.”

Godfrey told a campaigning group, the Financial Inclusion Commission last year that the systems used to deliver “auto-enrolment” – the scheme that ensures all low-income workers have a pension – could also be used to help the public insure themselves against “unexpected events.” That we have already paid national insurance and taxes already seems to have been overlooked here.

“There is a clear lesson from auto-enrolment that if you have a plumbing network or an infrastructure that works, that auto-enrolment infrastructure could be used for other things which would encourage financial inclusion: things like, for example, life cover, income protection and effective and very genuine personal contributory benefits for things like unemployment and sickness,” he said.

“They can be delivered at good value if there is mass participation through either soft compulsion or good behavioural economics.”

Ah yes, that great ideological Libertarian Paternalist pseudoscientific psychowaffle.

Note the context shift in the use of the term “inclusion”, which was originally deemed a democratic right, now it’s being discussed narrowly in terms of soft compulsion and individual responsibility. And an exchange of money.

Subtext: inclusion is only for those who can pay for it.

A report published by the Adam Smith Institute as far back as 1995 – The Fortune Account – also sets out proposals to replace “state welfare” with an insurance system “operated by financial institutions within the private sector.”

Mo Stewart has spent eight years researching the toxic and all-pervasive influence of the US insurance giant Unum over successive UK governments, and how it led to the introduction of the “totally bogus” and non-medical work capability assessment (WCA), which she says was designed to make it very much more difficult for sick and disabled people to claim out-of-work disability and sickness benefits.

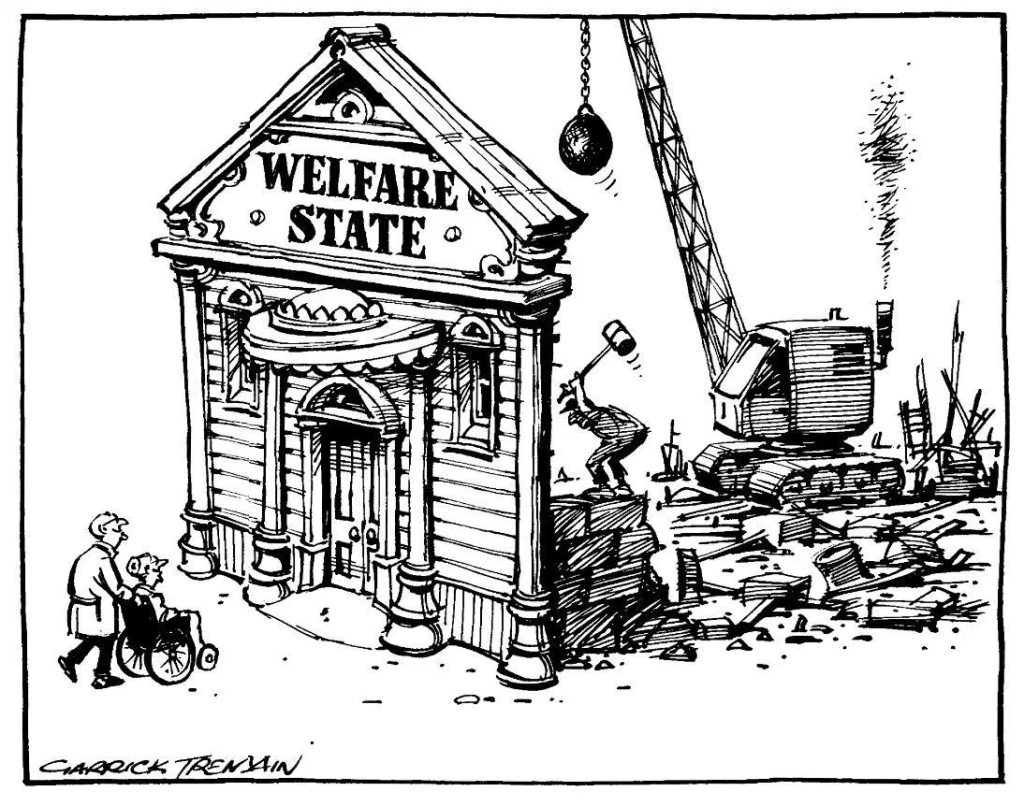

Stewart’s excellent book, Cash Not Care: The Planned Demolition Of The UK Welfare State, was published in September. She states that the assessment was modeled on methods used by the controversial company Unum to deny protection to seriously ill and disabled people in the US who had taken out income protection policies.

She goes on to say that the WCA was “designed to remove as many as possible from access to [employment and support allowance] on route to the demolition of the welfare state”, with out-of-work disability benefits to be replaced by insurance policies provided by private companies like Unum.

Stewart warns us that the UK is now close to adopting a US-style model.

She’s absolutely right.

Our public services are being privately auctioned. The multinational corporations are queuing up for the sale of the century in the UK. Smash and grab.

The public are picking up the tab.

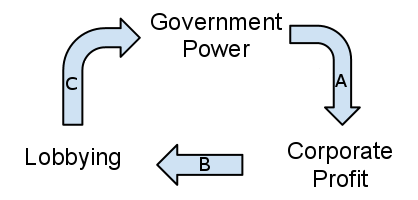

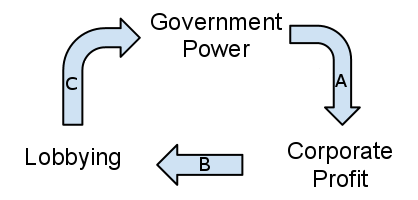

Rogue and antisocial corporations are writing public policies

Corporate lobbyists are primarily interested in a tactical investment. Whether facing down a threat to profits from a corporate tax raise, or pushing for market opportunities – such as government privatisations – lobbying has become simply another way of making a lot of money for a few people. Lobbyist messages are very carefully crafted and spun, especially in the media. The ultimate corporate goal is sheer self-interested profit-making, but this will always be dressed up to appear synonymous with the wider, national interest. At the moment, that means a collective chanting of the “economic growth”, supply side “productivity”, implied trickle down, “jobs” and “personal responsibility” neoliberal mantra.

Corporations (and governments) buy their credibility and utilise seemingly independent people such as academics with a mutual interest to carry their message for them. Some think tanks – especially free-market advocates like Reform or leading neoliberal think tank, the Institute of Economic Affairs – will also provide companies with a lobbying package: a media-friendly report, a Westminster event, meetings with politicians. The extensive Public Relations (PR) industry are paid to brand, market, engineer a following, build trust and credibility and generally sell the practice of managing the spread of information between an individual or an organisation (such as a business, government agency, the media) and the public.

PR is concerned with selling products, persons, governments and policies, corporations, and other institutions. In addition to marketing products, PR has been variously used to attract investments, influence legislation, raise companies’ public profiles, puting a positive spin on policies, disasters, undermining citizens’ campaigns, gaining public support for conducting warfare, and changing the public perception of repressive regimes.

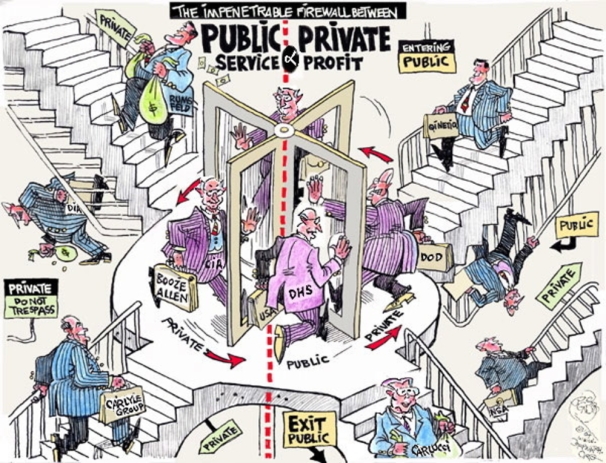

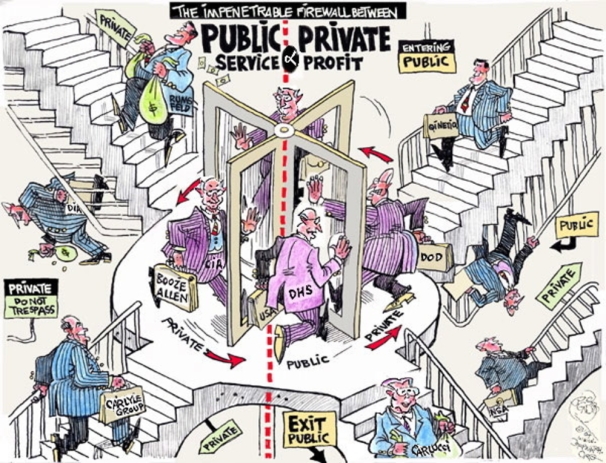

You can see how the revolving door of mutually exclusive political and corporate favour operates: it just keeps on spinning.

Edelman Intelligence and Westbourne, for example, are engaged in rebuttal campaigns and multimedia astroturfing projects to protect corporate interests:

“Monitoring of opposition groups is common: one lobbyist from agency Edelman talks of the need for “360-degree monitoring” of the internet, complete with online “listening posts … so they can pick up the first warning signals” of activist activity. “The person making a lot of noise is probably not the influential one, you’ve got to find the influential one,” he says. Rebuttal campaigns are frequently employed: “exhausting, but crucial,” says Westbourne.” From The truth about lobbying: 10 ways big business controls government

Edelman Intelligence is the world’s largest PR company and have been quietly visiting my own WordPress site over this last year, the link shows they were referred to my site from their own social media monitoring command centre. I’ve contacted the company to ask why, but have yet to receive a response. I’m not a paying client so it’s highly unlikely that the visits are in connection with promoting my best interests. Paying clients include the likes of Rupert Murdoch. (See footnote).

Unum’s long standing toxic influence on policy-making

In a recent press release, the delighted vulture capitalists at Unum say that they welcome the government’s recent Green Paper’s focus on Group Income Protection. The press release also says:

“Unum has welcomed the government’s recognition in a new Green Paper that “Group Income Protection policies have a much greater role to play in supporting employers to help people with health problems to stay in or return to work.

“The proposals were set out in Improving Lives: the Work, Health and Disability Green Paper, launched by the Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health, yesterday, 31 October 2016. As part of its efforts to enable “more people with long term conditions to reap the benefits of work and improve their health”, the Paper includes a number of proposals to prevent people falling out of work for health reasons and to make employers feel more confident about supporting disabled employees. In particular, it includes a number of specific policy ideas to increase the number of British workers with Group Income Protection (GIP).

“Through GIP, Unum has enabled thousands of people to return to work after long term sickness absences caused by mental health and musculoskeletal problems and other serious health conditions, including cancer and multiple sclerosis. Unum also provides training, support and advice to employers and line managers on how to look after employees with health problems and help them stay in or return to work.

“To increase the number of workers who benefit from GIP coverage, Unum is calling on the government to consider a temporary tax break for employers that buy GIP for their staff. This would reduce the number of people who fall out of work for health reasons, protect the finances of those who are unable to work and boost the productivity of UK businesses.”

In my critical analysis of the work, health and disability green paper, I said:

“And apparently qualified doctors, the public and our entire health and welfare systems have ingrained “wrong” ideas about sickness and disability, especially doctors, who the government feels should not be responsible for issuing the Conservatives’ recent Orwellian “fit notes” any more, since they haven’t “worked as intended,” presumably to make every single citizen economically productive from their sick beds.

So, a new “independent” assessment and some multinational private company will most likely very soon have a lucrative role to ensure the government get the “right results.”

The medical specialists are to be replaced by another profiteering corporate giant who will enforce a political agenda in return for big bucks from the public purse. Health care specialists are seeing their roles being incrementally and systematically de-professionalised. That means more atrocious and highly irrational attempts from an increasingly authoritarian government at imposing an ideological “cure” – entailing the withdrawal of any support and instead imposing punitive “behavioural incentives” – on people with medical conditions and physical disabilities.

Doctors, who are clever enough to recognise, diagnose and treat illness, are suddenly deemed by this government to be not clever enough to judge if patients are fit for work. It seems that the Conservatives don’t like competent witnesses who may challenge their droning ideologically-driven neoliberal psychobabbling. The neoliberal language of ‘incentives’ is a justification narrative for handing out financial rewards to the very wealthy, and making poor people even poorer. This incoherent narrative would have us believe that the rich are ‘incentivised’ by financial reward, bt the poor are ‘incentivised’ only by financial punishment.

The political de-professionalisation of medicine, medical science and specialisms (consider, for example, the implications of permitting job coaches to update patient medical files), the merging of health and employment services and the recent absurd declaration that work is a clinical “health” outcome, are all carefully calculated strategies that serve as an ideological prop and add to the justification rhetoric regarding the intentional political process of dismantling publicly funded state provision, and the subsequent stealthy privatisation of Social Security and the National Health Service.

De-medicalising illness is also a part of that process:

“Behavioural approaches try to extinguish observed illness behaviour by withdrawal of negative reinforcements such as medication, sympathetic attention, rest, and release from duties, and to encourage healthy behaviour by positive reinforcement: ‘operant-conditioning’ using strong feedback on progress.” Gordon Waddell and Kim Burton in Concepts of rehabilitation for the management of common health problems. The Corporate Medical Group, Department for Work and Pensions, UK.

Snakeoil salesmen. I don’t recall ill and disabled people consenting to be experimented upon or subjected to operant conditioning by raving, misanthropic, lunatic fringe quacks.

Medication, rest, release from duties, sympathetic understanding – remedies to illness – are being redefined as “perverse incentives” for “sickness behaviours”, yet the symptoms of an illness necessarily precede the prescription of medication, the Orwellian (and political rather than medical) “fit note” and exemption from work duties. Notions of “rehabilitation” and medicine are being redefined as behaviour modification: here it is proposed that operant conditioning in the form of negative reinforcement, which the authors seem to have confused with despotic punishment, will somehow “cure” ill health.

This is the same kind of thinking that lies behind welfare sanctions, which are state punishments entailing the cruel removal of lifeline income for “non-compliance” in narrowly and rigidly defined “job seeking behaviours.” Sanctions are also described as a “behavioural incentive” to “help” and “encourage” people into work. People who are ill, it is proposed, should be sanctioned, too, which would entail having their lifeline basic health care removed.

Many qualitative accounts from first hand witnesses, extensive research and empirical evidence has repeatedly demonstrated that welfare sanctions make it less likely that people will find employment: taking essential support from people with very limited resources profoundly demotivates, distresses and harms people, rather than “incentivising” them to find work. In fact it is more likely to cause an exacerbation of illness, harms, premature death or suicide. (See also: Benefits sanctions: a policy based on zeal, not evidence and The Nudge Unit’s u-turn on benefit sanctions indicates the need for even more lucrative nudge interventions, say nudge theorists.)

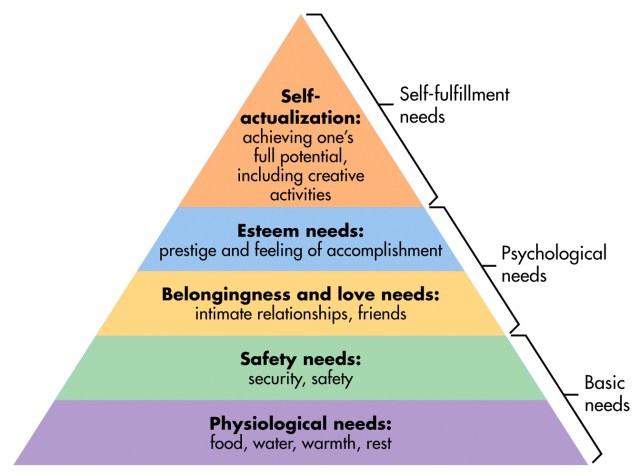

The darker meaning of David Cameron’s comment about “ending a culture of entitlement” back in 2010 has become clearer. He wasn’t only talking about a spiteful ideology, perceived attitudes and referencing erroneous, unverified and unfounded notions of “welfare dependency”: his party’s aim was and still is about reducing public expectations of a supportive and rights-based relationship with the publicly-funded state – one that has evolved from the post-war democratic settlement to ensure that everyone in the UK can meet their most basic human needs.

Poor and ill people cannot be simply punished (or “nudged”) out of being poor or ill.

Sanctions are a callous, profoundly antidemocratic, dysfunctional and extremely regressive form of economic terrorism; state violence which is founded entirely on traditional Conservative prejudices about poor people and rigid ideological assumptions. It is absolutely unacceptable that a government treats some groups, including some of the UK’s most vulnerable citizens, in such horrifically cruel and dispensable way, in a very wealthy, so-called civilised, first-world liberal democracy.

Unum also have a longstanding reputation for trying to reduce physical illness to “subjective states” and “faulty behaviours”, too. (See also: evidence submitted to the the select health committee by Professor Malcolm Hooper and Subjective symptom disability claims: Chronic Fatigue, Fibromyalgia and Multiple chemical sensitivity syndrome for example).

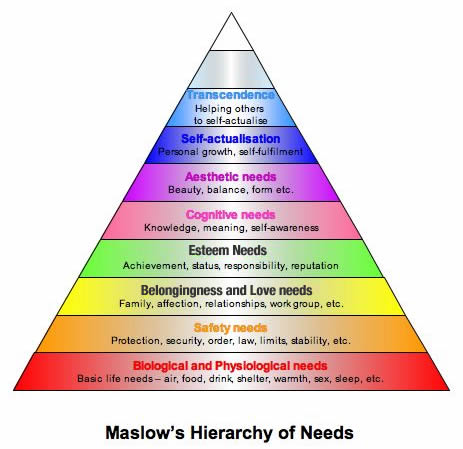

Even public policies that are supposed to address fundamental human needs arising from sickness and disability are tainted by a neoliberal idée fixe. The leitmotif is a total corporacratic commodification of human needs and relationships; building hierarchies of human worth within the closed and entropic context of a competitive market place, where resources are “scarce” and people are being herded; where the only holding principle that operates is profit over human need.

“In defiance of the substantial biomedical evidence submitted to its Guideline Development Group (GDG), NICE is recommending an inappropriate and potentially dangerous behavioural modification regime as the only management strategy for those with ME/CFS. NICE’s recommended management regime is promoted by a group (mainly psychiatrists) who have undeclared but undeniable competing financial interests.” Malcolm Hooper

It’s mind over matter and quids in

Behavioural medicine was partly influenced by Talcott Parsons’ The Social System, 1951, and his work regarding the sick role, which he analysed in a framework of citizen’s roles, social obligations, reciprocities and behaviours within a wider capitalist society, with an analysis of rights and obligations during sick leave. From this perspective, the sick role is considered to be sanctioned deviance, which disturbs the function of society. (It’s worth comparing that the government are currently focused on economic function and enhancing the supply side of the labour market.)

Behavioural medicine more generally arose from a view of illness and sick role behaviours as characteristics of individuals, and these concepts were imported from sociological and sociopsychological theories.

However, it should be pointed out that there is a distinction between the academic social science disciplines, which include critical perspectives of conflict and power, for example, and the recent technocratic “behavioural insights” approach to public policy, which is a monologue that doesn’t include critical analysis, and serves as prop for neoliberalism, conflating citizen’s needs and interests with narrow, politically defined economic outcomes.

We have a government that has regularly misused concepts from psychology and sociology, distorting them to fit a distinct framework of ideology, and justification narratives for draconian policies. Parsons’ work has generally been defined as sociological functionalism, and functionalism tends to embody very conservative ideas. From this perspective, sick people are not productive members of society; therefore this deviation from the norm must be policed. This, according to Parsons, is the role of the medical profession. More recently we have witnessed the rapid extension of this role to include extensive State policing of sick and disabled people.

It seems many of the psychosocial advocates have ignored the rise of chronic illnesses and the increasing pathologisation of everyday behaviours in health promotion. Parson’s sick role came to be seen as a negative referent (Shilling, 2002: 625) rather than as a useful interpretative tool. Parsons’ starting point is his understanding of illness as deviance. Illness is the breakdown of the general “capacity for the effective performance of valued tasks” (Parsons, 1964: 262). Losing this capacity disrupts “loyalty” to particular commitments in specific contexts such as the workplace.

Theories of the social construction of disability also provide an example of the cultural meaning of certain health conditions. The roots of this anti-essentialist approach are found in Stigma by Erving Goffman (1963), in which he highlights the social meaning physical impairment comes to acquire via social interactions. The social model of disability tends to conceptually distinguish impairment (the attribute) from disability (the social experience and meaning of impairment). Disability cannot be reduced to a mere biological problem located in an individual’s body (Barnes, Mercer, and Shakespeare, 1999). Rather than a “personal tragedy” that should be fixed to conform to medically determined standards of “normality” (Zola, 1982), disability becomes politicised. The issues we then need to confront are about the obstacles that may limit the opportunities for individuals with impairments, and about how those social barriers may be removed.

From a social constructionist perspective, emphasis is placed on how certain illnesses come to have cultural meanings that are not reducible to or determined by biology, and these cultural meanings further burden the afflicted (as opposed to burdening “the tax payer” , the health services, those with profit seeking motives, or the state.)

So to clarify, it is wider society and governments that need a shift in disabling attitudes, perceptions and behaviours, not disabled people.

The insights that arose from the social construction of disability approach are embodied in policies, which include the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, which included an employers’ duty to ensure reasonable adjustments/adaptations; the more recent Equality Act 2010 and the Human Rights Act 1998, which provides an important tool for disabled people to use to challenge discrimination, violations to their human rights and unacceptable treatment.

In contrast, Parsons invokes a social contract in which society’s “gift of life” is repaid by continued contributions and conformity to (apparently unchanging, non-progressive) social expectations. For Parsons, this is more than just a matter of symbolic interaction, it has far more concrete, material implications: “honour” (deserving) and “shame” (undeserving) which accompany conformity and deviance, have consequences for the allocation of resources, for notions of citizenship, civil rights and social status.

Parsons never managed to accommodate and reflect social change, suffering and distress, poverty, deprivation and conflict in his functionalist perspective. His view of citizens as oversocialised and subjugated in normative conformity was an essentially Conservative one. Furthermore, his systems theory was heavily positivistic, anti-voluntaristic and profoundly dehumanising. His mechanistic and unilinear evolutionary theory reads like an instruction manual for the capitalist state.

Parsons thought that social practices should be seen in terms of their function in maintaining order and social structure. You can see why his core ideas would appeal to Conservative neoliberals and rogue multinational companies. Conservatives have always been very attached to tautological explanations (insofar that they tend to present circular arguments. One question raised in this functional approach is how do we determine what is functional and what is not, and for whom each of these activities and institutions are functional. If there is no method to sort functional from non-functional aspects of society, the functional model is tautological – without any explanatory power to why any activity is regarded as “functional.” The causes are simply explained in terms of perceived effects, and conversely, the effects are explained in terms of perceived causes).

Because of the highly gendered division of labour in the 1950s, the body in Parsons’ sick role is a male one, defined as controlled by a rational, purposive mind and oriented by it towards an income-generating performance. For Parsons, most illness could be considered to be psychosomatic.

The “mind over matter” dogma is not benign; there are billions of pounds and dollars at stake for the global insurance industry, which is set to profit massively to the detriment of sick and disabled people. The eulogised psychosocial approach is evident throughout the highly publicised UK PACE Trial on treatment regimes that entail Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and graded exercise. By curious coincidence, that trial was also significantly about de-medicalising illnesses. Another curious coincidence is that Mansel Aylward sat on the PACE Trial steering group.

Here is further evidence that government policy is not founded on empirical evidence, but rather, it is often founded on deceitful contrivance. A Department for Work and Pensions research document published back in 2011 – Routes onto Employment and Support Allowance – said that if people believed that work was good for them, they were less likely to claim or stay on disability benefits.

It was decided that people should be “encouraged” to believe that work was “good” for health. There is no empirical basis for the belief, and the purpose of encouraging it is simply to cut the numbers of disabled people claiming ESA by “encouraging” them into work. Some people’s work is undoubtedly a source of wellbeing and provides a sense of purpose. That is not the same thing as being “good for health”. For a government to use data regarding opinion rather than empirical evidence to claim that work is “good” for health indicates a ruthless mercenary approach to fulfill their broader aim of dismantling social security and to uphold their ideological commitment to supply-side policy.

From the document: “The belief that work improves health also positively influenced work entry rates; as such, encouraging people in this belief may also play a role in promoting return to work.”

The aim of the research was to “examine the characteristics of ESA claimants and to explore their employment trajectories over a period of approximately 18 months in order to provide information about the flow of claimants onto and off ESA.”

The document also says: “Work entry rates were highest among claimants whose claim was closed or withdrawn suggesting that recovery from short-term health conditions is a key trigger to moving into employment among this group.”

“The highest employment entry rates were among people flowing onto ESA from non-manual occupations. In comparison, only nine per cent of people from non-work backgrounds who were allowed ESA had returned to work by the time of the follow-up survey. People least likely to have moved into employment were from non-work backgrounds with a fragmented longer-term work history. Avoiding long-term unemployment and inactivity, especially among younger age groups, should, therefore, be a policy priority. ”

“Given the importance of health status in influencing a return to work, measures to facilitate access to treatment, and prevent deterioration in health and the development of secondary conditions are likely to improve return to work rates”

Rather than make a link between manual work, lack of reasonable adjustments in the work place and the impact this may have on longer term ill health, the government chose instead to promote the cost-cutting and unverified, irrational belief that work is a “health” outcome. Furthermore, the research does conclude that health status itself is the greatest determinant in whether or not people return to work. That means that those not in work are not recovered and have longer term health problems that tend not to get better.

Work does not “cure” ill health. To mislead people in such a way is not only atrocious political expediency, it’s actually downright dangerous.

As neoliberals, the Conservatives see the state as a means to reshape social institutions and social relationships based on the model of a competitive market place. This requires a highly invasive power and mechanisms of persuasion, manifested in an authoritarian turn. Public interests are conflated with narrow economic outcomes. Public behaviours are politically micromanaged. Social groups that don’t conform to ideologically defined economic outcomes are politically stigmatised and outgrouped.

Nudging, Unum and the behaviourist turn in medicine.

The history of medicine and definitions of illness and disability are being re-written for the insurance industry, by neoliberal “small state” ideologues and anti-welfarist governments.

Formally instituted by Cameron in September 2010, the Behavioural Insights Team, (otherwise known as the Nudge Unit), which is a part of the Cabinet Office, is made up of people such as David Halpern, who co-authored the Cabinet Office report: Mindspace: Influencing Behaviour Through Public Policy, which comes complete with a cover illustration of the human brain, with an accompanying psychobabble of decontextualised words such as “incentives”, “habit’, “priming” and “ego.” It’s all just a stock of inane managementspeak. Neoliberal psychobabbling and strategies of psycho-compulsion.

The report addresses the needs of policy-makers. Not the public. The behaviourist educational function made explicit through the Nudge Unit is now operating on many levels, including through policy programmes, forms of “expertise”, and through the State’s influence on citizens, the mass media, other cultural systems and at a subliminal level: it’s embedded in the very language that is being used in political narratives.

The increasing focus on social control and conformity in public policy design and governing has been dubbed “neuroliberalism”, reflecting something of a behaviourist turn. It draws on social marketing as a policy tool, in which principles from private marketing and advertising are applied to the definition and promotion of “good” behaviours. Deviance (“bad” behaviour) is defined politically through the intentional and systematic stigmatisation of already marginalised social groups, leading to the creation of folk devils and moral panic which is amplified and perpetuated by the media.

Othering and outgrouping have become common political practices.

This serves to desensitise the public to the circumstances of marginalised social groups and legitimises neoliberal “small state” policies, such as the systematic withdrawal of state support for those adversely affected by neoliberalism, and it also justifies inequality. By stigmatising the poorest citizens, a “default setting” is established regarding how the public ought to perceive and behave towards defined outgroups.

Policies directed at the poorest and some of the most vulnerable citizens are being used to extend behaviour modification techniques, based on methodological behaviourism. This is a psychocratic approach to administration: the government are delivering public policies that have an expressed design and aim to act upon individuals, with an implicit set of instructions that inform citizens how they should be.

Aversives and punishment protocols are being used on the public. Coercive and harshly conditional welfare policies are one example of this.

The origin of active welfare (the idea that the social security system should reflect that the habitually “idle poor” need coercing into work), founded on the idea that poor people are the cause of their own poverty because of their cognitive and behavioural flaws – they fail to take advantage of the opportunities “available” to them – lies with the US neoliberal right.

Charles Murray and Lawrence Mead clearly made an impact on the international policy debate in the 1980s, partly due to the legitimisation that they received from the support of the Reagan and Thatcher administrations for their central claims. They were particularly influential in the growth of work fare and a welfare system based on punishment and psycho-compulsion. Murray claimed the underclass of poor people avoid work because of the “overgenerous” nature of welfare benefits. Mead argued that a “culture of poverty” meant that workfare policies are required to “reintegrate” and “incentivise” the unemployed poor.

In the UK, James Purnell, one of the work and pensions secretaries for New Labour, said: “For those who play by the rules, there is a world of opportunity. But for those who don’t, there will be clear consequences from their behaviour”.

He sounds rather like an authoritarian Victorian headmaster.

So what exactly are “the rules”, and who has made them?

Government policies are expressed political intentions regarding how our society is organised and governed. They have calculated social and economic aims and consequences. In democratic societies, citizens’ accounts of the impacts of policies ought to matter.

However, in the UK, the way that policies are justified is being increasingly detached from their aims and consequences, partly because democratic processes and basic human rights are being disassembled or side-stepped, and partly because the government employs the widespread use of linguistic strategies: euphemisms, superficial glittering generalities and techniques of persuasion to intentionally divert us from aims and consequences of ideologically (rather than rationally) driven policies. Furthermore, policies have become increasingly detached from public interests and needs.

Neoliberal anti-welfarism, amplified by a corporate media, has aimed at reconstruction of society’s “common sense” assumptions, values and beliefs. Class, disability and race narratives in particular, associated with traditional prejudices and categories from the right wing, have been used to nudge the UK to re-imagine citizenship, human rights and democratic inclusion as highly conditional.

Illness is all in the mind: conforming to roles and academically constructed stereotypes

“Diagnosis elicits the belief the patient has a serious disease, leading to symptom focusing that becomes self-validating and self-reinforcing and that renders worse outcomes, a self-fulfilling prophecy, especially if the label is a biomedical one like ME. Diagnosis leads to transgression into the sick role, the act of becoming a patient even if complaints do not call for it, the development of an illness identity and the experience of victimization”. Simon Wessely and Marcus S.J. Huibers: The act of diagnosis: pros and cons of labelling chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychological Medicine 2006: 36

In 1993, Mansel Aylward invited psychiatrist Simon Wessely to give a presentation on his biopsychosocial approach to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome before the then Minister for Social Security. Wessely claimed: “As regards benefits:- it is important to avoid anything that suggests that disability is permanent, progressive or unchanging. Benefits can often make patients worse.”

“Benefits can often make patients worse.” I think he meant the patient’s illness is made worse. Despite there being little empirical evidence for these claims, the Minister for Social Security was looking to cut spending, so self-styled “experts” were more useful to an expedient government than rigorous research. I think it would be true to say that without social security, many people who are disabled because of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) would experience MUCH worse symptoms, as indeed people with other chronic illnesses would, and some would undoubtedly die without lifeline support to enable them to meet their basic survival needs.

ME action UK say that on May 17, 1995, Wessely was one of the main speakers at a Unum-supported symposium held in London entitled “Occupational Health Issue for Employers” (where ME was described as “the malingerers’ charter”) at which they advised employers how to deal with employees who were on long-term sickness absence with “CFS”. Moreover, in UNUM’s “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Management Plan”, ME/CFS is described as “Neurosis with a new banner” and the same document states “UNUM stands to lose millions if we do not move quickly to address this increasing problem”.

Unum have been advising UK governments since at least 1994, when the Conservative government hired John LoCascio, second vice-president of giant and scandalous US disability insurance company, Unum, to advise on reducing the numbers successfully claiming Incapacity Benefit (IB). He joined the “medical evaluation group”.

Another key figure in the group was Mansel Aylward. The group devised a stringent “all work test”. Approved doctors were trained in Unum’s approach to “claims management”. That’s basically managing not to pay people what they are entitled to. The rise in IB claimants came to a halt. However, it did not reduce the rising numbers of claimants with mental health problems.

Supporters of the behaviourist “non-medical” model of disability and illness include Mansel Aylward, Dame Carol Black, Lord Freud and Lord Kirkwood of Kirkhope (the chairman of the Unum customer advisory panel, whilst he was also Chair of the UK parliament’s Work and Pensions Select Committee).

Of course there is the lowest common denominator for highest possible private profits in operation in the US and UK. Some names keep recurring, like the proverbial bad penny for bad thoughts. The controversial PACE trial is just another small variation of the leitmotif. Recently an information tribunal rejected a university’s £200,000 attempt to prevent release of data from the controversial medical trial, that was the first to receive Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) funding.

The PACE trial mirrors Unum’s previous systematic and wholly non scientific de-medicalisation and subsequent trivialisation of serious illnesses such as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) and Fibromyalgia in the US, and has led to the growth and standardisation of “behavioural” medical treatment regimes, such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), which is often used to reduce the use of pharmacological pain relief in a wide range of chronic illnesses, including connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

The World Health Organisation classified these illnesses as physical diseases, now they are being reconstructed as “psychosocial” phenomena, with recovery supposedly being dependent on the sick person’s attitude and mindset, by greedy crony capitalists and ideologically expedient neoliberal “small state” anti-welfarist governments.

This current psychosocial approach to medical conditions is about addressing a perceived need for cognitive and behavioural change: it allegedly addresses patient’s “attitudes and perceptions” of their condition, their “coping mechanisms” or lack of them, and perceptions of pain and its “management”. None of this affects the underlying disease activity or the damage that disease processes cause to the body. It’s worse than speculative nonsense.

The trial assessed the value of “biopsychosocial” interventions at the same time as the DWP was using the biopsychosocial model of disability to help justify cuts to disability spending.

The absurd consequences of allowing a vulture capitalist insurance multinational to write sickness and disability public policies

It’s an interesting observation that Mansel Aylward, who was a key architect of the last decade’s welfare “reforms”, had helped to secure funding for the PACE Trial and sat as an “observer” on the trial’s steering committee. The DWP co-funded the trial. The failure to release the results for the pre-specified analyses laid out in the PACE trial’s protocol is of concern as it had already been noted that there was a likely ideological bias of the trial’s three principal investigators.

All three investigators have invested in developing careers founded on the development of biopsychosocial interventions for CFS, and the two who had been part of the Chief Medical Officer’s CFS working group both resigned because the active biopsychosocial approaches of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Graded Exercise Therapy (GET) were not endorsed over “pacing” in the way that they had wanted. (See Chronic fatigue report delayed as row breaks out over content. The British Medical Journal, 2002, and Power-sharing, not a take-over, 2002.)

All three principal investigators also reported conflicts of interest involving the insurance industry. There has long been concern about private insurance companies influencing changes to undermine the UK welfare state, a system of social insurance that they currently compete against. (See Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial, 2011 and “In the Expectation of Recovery” MISLEADING MEDICAL RESEARCH AND WELFARE REFORM, George Faulkner, 2016).

“Back in 1995 a Unum report on CFS stated that they could “lose millions if we do not move quickly to address this increasing problem”. It was argued that CFS claims should be managed “more aggressively and in a proactive rather than a reactive fashion” while attempting to present CFS as “neurosis with a new banner”. Emphasising the importance of psychosocial factors and classing CFS as a mental health problem could bring immediate financial benefits to insurance companies when policies limit payouts for mental health problems.

“One of the PACE trial’s principal investigators gave a presentation on the results of the PACE trial to Swiss Re insurance. Swiss Re’s report of his talk detailed the potential use of mental health exclusions to cut payments, while a 2013 Swiss Re presentation on their approaches to mental health problems describes their use of specific exclusions for CFS and ME.

“During the Swiss Re presentation on PACE no mention seems to have been made of the fact that PACE found neither CBT nor GET were associated with improved employment outcomes, and instead Swiss Re’s claims managers continued to be encouraged to believe that promoting these active rehabilitative approaches would assist return to work. There has been concern about insurance companies pushing some patients with CFS to take part in CBT and GET against their wishes.

“A response to the paper which published the PACE trial’s data on employment outcomes was titled Coercive practices by insurance companies and others should stop following the publication of these results, but has yet to receive a response from the PACE team.” George Faulkner, 2016

From 1996 to April 2005 Mansel Aylward was chief medical adviser, medical director and chief scientist of the UK Department for Work and Pensions and chief medical adviser and head of profession at the veteran’s agency, Ministry of Defence. He was involved in the establishment of the new Work Capability Assessment. When he left the department, he headed the UnumProvident Centre for Psychosocial and Disability Research, at Cardiff University. (The centre has since been renamed and Unum claim they no longer provide any funding – no doubt because of the claims that academic integrity could be called into question by its influence.)

The Scientific and Conceptual Basis of Incapacity Benefits by Gordon Waddell and Mansel Aylward, followed by the 2006 report: Is work good for your health and well-being by Gordon Waddell and Kim Burton, were both very influential reports that were commissioned by the DWP and so inclined towards ideologically biased outcomes from the start. Both reports were produced when Aylward and Waddell were sponsored by UnumProvident – Centre for Psychosocial and Disability Research ( at Cardiff University) – with funding of course from Unum Provident, from 2004-2009.

In January 2003, an influential book, Malingering and illness deception was published as a very large hymn crib sheet that was to inform political rhetoric, media justification narratives and the subsequent welfare “reforms.” It was also funded by the DWP, with telltale dogma and schematic contributions from Gordon Waddell, John LoCascio of UNUM Provident Insurance Company, and of course there is this telling acknowledgment:

“The meeting which formed the basis for this book would not have been possible had it not been for the enthusiastic support of Professor Mansel Aylward and funding from the Department for Work and Pensions.”

The book has political agenda-setting chapter sub-headings such as: Investigating benefit fraud and illness deception in the United Kingdom, Malingering, insurance medicine, and the medicalization of fraud and Wilful deception as illness behaviour.

Unum insidiously built up credibility and influence in Britain. The company appointed Mansel Aylward as director of their Centre for Psychosocial and Disability Research, following his retirement from the DWP. The launch event was attended by Archie Kirkwood, who was appointed chair of the House of Commons select committee on work and pensions. Malcolm Wicks, minister of state in the DWP, gave a speech praising the “partnership between industry and the university.”

The whole aim of the centre was to transform the ideological paradigm of welfare from one based on a rights-based post-war collectivism to one increasingly enclosed by a responsibility-based individualism and so help develop the market for Unum’s products. In 2005, the centre produced The Scientific and Conceptual Basis of Incapacity Benefits (TSO, 2005) written by Aylward and colleague Gordon Waddell. It provided the conceptual framework for the 2006 welfare reform bill.

Of course the more recent widespread criticism of “Atos” assessments in the UK has been beneficial to Unum as it undermines confidence in state provision of disability benefits. Such a profound loss of confidence makes it much easier to sell alternatives: private insurance.

Its methodology is the same one that informs Unum’s approach. Is work good for your health and well-being by Gordon Waddell and Kim Burton was also a very influential report, both were also commissioned by the DWP and so inclined towards ideologically biased outcomes from the start. Just to be clear, both reports were produced when Aylward and Waddell were sponsored by UnumProvident – Centre for Psychosocial and Disability Research (the Centre) at Cardiff University, with funding by Unum Provident, from 2004-2009.

Among the spurious ideas used to justify cutting lifeline social security support is that disabled and ill people are not working because of an “internalisation of the sick or “patient” role as the dominant feature of their lives,” and that “work is good for health.”

In a memorandum submitted to the House of Commons select committee on work and pensions, Unum define their method of working: “Our extended experience […] has shown us that the correct model to apply when helping people to return to work is a biopsychosocial one.”

The emphasis, however, is on the “psychosocial”. This shifts the focus from the medical conditions that cause disability and illness to the behaviours and perceptions of patients and ultimately, to neoliberal notions of personal responsibility and self-sufficient citizenship in a context of a night watchman, non-welfare state.

Waddell and Aylward adopted the same arguments in their monograph. Disease is the only form of objective, medically diagnosable pathology. Sickness is a temporary phenomenon. Illness is a behaviour. Incapacity Benefit trends are a social phenomenon rather than a health problem. The solution is not to cure the sick, but a “fundamental transformation in the way society deals with sickness and disabilities” (p123). The goal and outcome of treatment is work, because work is therapeutic.

Worklessness is a serious risk to life. It is “one of the greatest known risks to public health: the risk is equivalent to smoking 10 packets of cigarettes per day” (p17). And: “No-one who is ill should have a straightforward right to incapacity benefit.”

David Freud adopts the same spurious psychosocial approach in a report that formed a review of the government’s Welfare to Work strategy. He cites Waddell and Burton: “Work is good for health.” (From “Is Work Good for your Health and Well-Being”, 2006)

Aylward has been widely criticised for giving “academic” credibility to the biopsychosocial model which was said to be the basis of the Cameron government’s disability benefits “reforms”. Aylward prepared reports that were quoting “illness belief” as being a supposedly more likely cause for many “common mental health conditions” or “musculoskeletal conditions”. There were repeated references made in some of his and Gordon Waddell’s research to alleged “malingering” by patients.

“Obstacles to recovery and return to work are primarily personal, psychological and social rather than health-related “medical” problems.”

“Beliefs, perceptions and personal responses lie at the heart of the problem [of worklessness through ill health].” Worklessness and Health: A Symposium – Mansel Aylward.

It’s worth noting that the “musculoskeletal conditions” include backache, pulled ligaments and muscles, injured tendons, prolapsed spinal discs, sciatica – all of which a person may fully recover from. This category of conditions also includes osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and more serious and chronic illnesses caused by connective tissue disease – most people do not recover from these, and the biological damage that this family of diseases cause is not just confined to the musculoskeletal system. By using such a broad category of wide-ranging conditions, this effectively trivialises the most serious and often progressive diseases in the category.

This is why I visit my doctor, and not the government or a “researcher” with a vested interest, when I am unwell. I don’t believe anyone was ever cured by ideology. Nor do I believe work is a “health” outcome. If the protestant work ethic is such an effective cure for disease, the Victorian era “trial” certainly didn’t provide any empirical evidence of that in the premature mortality rates. In fact both men and women were debilitated by the age of forty. Poor nutrition, long hours and premature full-time employment all contributed to a short life expectancy. (Daily Life in Victorian Britain, Sally Mitchell, 1996.)

Although life span slowly increased within the Victorian age, notably as treatment became more advanced, surgery more effective, and medical knowledge more extensive, the average life span in 1840, in the Whitechapel district of London, was 45 years for the upper class and 27 years for tradesman. Laborers and servants lived only 22 years on average. (Victorian Britain Encyclopedia, Sally Mitchell, 1988.)

Aylward claims that the principal negative influences on return to work are: Personal / psychological: Catastrophising pain (even minor degrees). Low Self-Efficacy. Social: Lone parenthood / unstable relationships – being a “Victim” of modern society in rented or social housing. General Affect: Being sad or low most of the time: Pervasive thoughts about personal illness. Cognitive: Minimal health literacy. Self-monitoring (symptoms). False beliefs. Economic: Availability of alternative sources of income / support such as the availability of health care and welfare. (Pages 15-16).

“Catastrophising pain” is a phrase that crops up in a lot of biopsychosocial texts. It’s another of those made up words and phrases, like “worklessness”, “making work pay” and “culture of dependency” which are just ideological signposts to neoliberal notions of competitive individualism, anti-welfarism and personal responsibility, without any reference to reality. And if you make a claim that sickness and pain are “subjective”, surely attempts to describe how other people subjectively experience sickness and pain is even more subjective.

And accusing someone else of holding false beliefs regarding their own state? Really? You can’t get further away from empirically verifiable statements than that.

The UK government and the Reform think tank claim that the availability of social security serves as a “disincentive” for ill and disabled people to return to work. The cuts to essential lifeline support for people who are ill and disabled that have been embedded in the systemic welfare “reforms” are all about “promoting economic self-sufficiency.”

However, that is precisely what public national insurance contributions are about. The idea originally was that social provision should be designed to protect people from the ravages of absolute poverty and capitalism – it was intended to support poor citizens – and to speculate that such support actually makes people poor is simply incoherent pseudoscientific nonsense and derisory political posturing from the “private” state neoliberals.

Aylward highlights more than once on his writing a perceived tension between “disability rights” and state notions of “benefit dependency.” (for example, on Page 8 of Worklessness and Health: A Symposium).

Yet Unum say: “And contrary to popular belief, if your employees are aware of benefits – such as private health insurance or Income Protection – they are not likely to take more time off sick. Cass’ research shows that communicating about a wide range of employee benefits actually builds employee engagement and a more loyal workforce that takes less time off sick.” Unum: How to communicate your employee benefits package.

However, there are conflicting messages to employers on this issue: “Sick-pay provisions may also encourage or discourage absence, and it is important that an organisation monitors and analyses its absence recording systems in order to pick up any perverse behaviours being driven by the sick-pay schemes. For example, it is not uncommon to see spikes of return to work when an absent employee moves to half pay or no pay.”

The cure for sick leave is work and other gems of wishdom

The biopsychosocial model has become a disingenuous euphemism for psychosomatic illness, which has been exploited by medical insurance companies and by governments keen to limit or deny access to social security, medical and social care.

This approach to disability and ill health has been used to purposefully question the extent to which people claiming social security bear personal responsibility for their own health status, rehabilitation and prompt return to work. It also leads to the alleged concern that a welfare system which provides a livable income to those with disabling health problems may provide “perverse incentives” for perverse behaviours, entrenching “worklessness” and a “culture of dependency”. It’s worth pointing out at this point that there has never been any empirical evidence to support the Conservative notion of welfare “dependency”.

Instead of being viewed as a way of diversifying risk and supporting those who have suffered misfortune, social and private insurance systems are to be understood as perverse incentives that pay people to remain ill and keep them from being economically productive.

The government have made it clear that there are plans to merge health and employment services. In a move that is both unethical and likely to present significant risk of harm to many patients, health professionals are being tasked to deliver benefit cuts for the DWP. This involves measures to support the imposition of work cures, including setting employment as a clinical outcome and allowing medically unqualified job coaches to directly update a patient’s medical record.

The Conservatives (and the Reform think tank) have proposed mandatory treatment for people with long term conditions (which was first flagged up in the Conservative Party Manifesto) and this is currently under review, including whether benefit entitlements should be linked to “accepting appropriate treatments or support/taking reasonable steps towards “rehabilitation”. The work, health and disability green paper and consultation suggests that people with the most severe illnesses in the support group may be subjected to welfare conditionality and sanctions.

Such a move would have extremely serious implications. It would be extremely unethical and makes the issue of consent to medical treatment very problematic if it is linked to the loss of lifeline support or the fear of loss of benefits. However this is clearly the direction that government policy is moving in and represents a serious threat to the human rights of patients and the independence of health professionals.

Behavioural medicine is prevalent in the United States, where many health problems are primarily viewed as behavioural in nature, as opposed to medical. The biopsychosocial model of illness has encouraged unsubstantiated claims that “positive attitude” or “fighting spirit” can help slow cancer and other progressive diseases, which may be very harmful to the patients themselves. Patients may come to believe that a poor prognosis or their poor progress results from “not having the right attitude”, when in fact it is most likely through no fault of their own.

Increasingly, insurers, policy makers and employers are pressing for policies that would redistribute expenses resulting from what they regard to be “voluntary” health risks to those who “choose” to take such risks.

Of course the long term aim of the Conservatives is to dismantle social security and the National Health Service (NHS) – free health care provision – entirely. Access to health care in the UK is currently being rationed because of the government’s systematic cuts to the NHS budget, and payments for some treatments have been introduced by stealth.

Unum say: “The Green Paper also calls for proposals to overhaul sickness certification and GPs’ approach to Fit Note. Unum has been calling for reform of Fit Notes so more people are able to access the right support to return to work as soon as possible.”

By that phrase “the right support” the predatory private company are simply singing from the same crib sheet as the government. Lots of mutual back patting and private handshakes have sealed the deal of doom for the welfare state long ago. The “right support” simply entails removing any support at all for ill and disabled people so that they are forced to work or starve and become destitute.

Unum’s modus operandi in the US was based on the unscrupulous practice of putting profit over human health. A 2004 investigation determined the practice began as early as 1994, and a CBS 60 Minutes report revealed the company established a quota for denied claims and actually offered incentives to employees who denied valid claims from policyholders. The company also delayed claims to make profit.

Unum was forced by state regulators to re-open 290,000 disability insurance claims that had been rejected, including a case where “Unum insisted that a man who had quintuple bypass surgery was fit to go back to his job at a stock brokerage firm, even though his doctors said the stress might kill him” and also, where Unum “refused benefits to a man who had had multiple heart attacks”.

An investigation in California found that Unum systematically violated state insurance regulations and fraudulently denied claims using phony medical reports, policy misrepresentations, and biased investigations. The rogue company admitted to only reviewing 10 percent of the eligible cases for reopening under the terms of their legal settlement reached three years earlier.

Unum’s callous profiteering and illegal behaviour led California Insurance Commissioner John Garamendi to state that “UnumProvident is an outlaw company. It is a company that for years has operated in an illegal fashion.” A Yale University research paper commented that, with regards to Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) and other cases, Unum was “engaged in a program of deliberate bad faith denial of meritorious claims.”

Yet this is the company admired and unscrupulously hired by UK governments as a “leader” in dealing unscrupulously with disability claims, and violating the human rights of disabled people.

The cooperation between the UK government and Unum stems entirely from a community of mutually vested interests between them, with both the corporate vultures and their allies in government wishing to reduce the amount of people who are able to claim disability through sickness; the government so it can pay less and less of our money in social security to people who need to draw on their national insurance for support and the insurance company so it can profitably contest or refuse more insurance claims.

So, after the systematic cuts to social security have been persistently justified by an alleged need to “change the behaviours” of poor people and to “incentivise” them into work, we now have behavioural change treatments becoming more prominent in health care and medicine. In the same way that poor people are held responsible for poverty, ill people are held responsible for illness. Just as ministers claim that poor people are a “burden” on public services and tax payers, now they are saying ill people are a burden on the NHS and tax payers… just take a moment to think that through.

Seems the neoliberal fundamentalist Conservatives believe that public services shouldn’t address the needs of… the public.

The Conservatives came up with an idea that will kill two birds with one stone, as it were. They decided to demand that poor people think work is good for health. They plan to combine the goals of job centres and GP surgeries. Job coaches are the new health care professionals, apparently. Of course that anti-welfare and anti-health care strategy won’t change a thing, except to make people who are ill and out of work even more miserable, poor and ill.

Political authoritarianism, neoliberalism and façade democracy present a tragicomedy that creates the ultimate experimental théâtre de l’absurde, transforming lucrative big business propositions of crony capitalism into Schadenfreude; groaning clichés and stereotypes, political scapegoats and outgroups. Irrational, anecdotal populist “common sense” soundbites become incoherent, cognitive dissonance-inducing justification narratives. For ordinary citizens this fanfares increasingly irrational and draconian policies – the “science” of imaginary solutions to fictitious citizen “behavioural” problems in a Théâtre de la Cruauté (cruelty) – because of a strong motivation to control, rule and empty the public purse into private bank accounts (usually offshore), rather than recognise public needs and interests, and include the masses in democratic decision-making and the economy.

The government think that social justice is actually about “incentivising” those at the wrong end of politically constructed socioeconomic problems with punishments. I’m surprised we haven’t seen the reintroduction of public thrashings, flogging and the ducking stool. Meanwhile the people responsible for hoarding all the wealth and causing poverty for others – and to a considerable degree, contributing to health inequalities too – well they get the deluxe package of privileged incentives – tax cuts, high esteem, status and a pat on the head just for being sanctimonious, greedy, grasping, antisocial money hoarders, enforcing the equivalent of an economic enclosure act. They also have a lot of power and freedom, and so get to write a lot of policies that help them make profits and thus hoard even more of what was once our public wealth.

It’s curious how ministers claim that throwing money at a problem doesn’t change it. They’re right: the very worst of the hoarding and wealthy elite remain the biggest socioeconomic problem with faulty behaviours that we face as a society.

But poor people are poor because of a lack of money. Taking more money from them that they don’t have won’t cure poverty. You can’t thrash wealth into someone. You can’t thrash poverty out of someone. I really should not have to explain that like a patient parent explains the way things work to a toddler. But the Conservatives have a form of arrested development, and cling to their reductionist rituals of ontological security. They refuse to learn. The government are too busy telling us how they think society ought to be, they never have time or an inclination to listen to mere citizens. Big businesses take up every shred of their attention.

We know from recent history that once the Conservatives start to hold people responsible for problems that are not their fault, the public institutions that support people facing social difficulties are in peril – usually through the increasing privatisation of services, and ultimately, through the dismantling and transformation of publicly funded social support mechanisms to purely private profit generating mechanisms for the crony vulture capitalists. The only people set to gain in the long term from all of this political destruction and mis-spending from the public purse are the big vulture capitalist insurance companies, who have also had a hand in the construction of narratives of “personal responsibility” economic self sufficiency, thrift and self help. Perhaps Neoliberal governments should develop a policy of providing invisible bootstraps for citizens to pull themselves up from the damage being inflicted on them from a great height.

When you hear the same incoherent crib sheet responses over and over, and see the intentional political stigmatisation of social groups, you come to recognise the pattern of preemptive justificationism and the malicious and greedy intent behind the draconian policies.

It’s goodbye to the welfare state, the NHS and democracy, and hello to the new wealth care.

The ministry of plenty say that private interest is public interest.

All hail the corporatocracy.