Correlation isn’t quite the same as causality. When researchers talk about correlation, what they are saying is that they have found a relationship between two, or more, variables. “Correlation does not mean causation” is a quip that researchers chuck at us to explain that events or statistics that happen to coincide with each other are not necessarily causally related.

Correlation means that an association has been established, however, and the possibility of causation isn’t refuted or somehow invalidated by the establishment of a correlation. Quite the contrary. Indeed an established association implies there may also be a causal link. To prove causation, further research into the association must be pursued. So, care should be taken not to assume that correlation never implies causation, because it quite often does indicate a causal link.

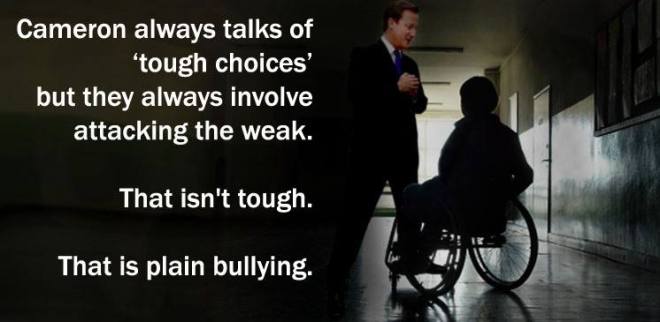

Whilst the government deny there is a causal link between their welfare policies, austerity measures and an increase in premature deaths and suicides, they cannot deny there is a clear correlation, which warrants further research – an independent inquiry at the VERY least. But the government are hiding behind this distinction to deny any association at all between policy and policy impacts. That’s just plain wrong.

Correlations between two things may be caused by a third factor that affects both of them. This sneaky, hidden third factor is called a confounding variable, or simply a confounder.

However, most of the social research you read tends to indicate and discuss a correlation between variables, not a direct cause and effect relationship. Researchers tend to talk about associations, not causation. Causation is difficult but far from impossible to establish, especially in complex sociopolitical environments. It’s worth bearing in mind that establishing correlations is crucial for research and show that something needs to be examined and investigated further. That’s precisely how we found out that smoking causes cancer, for example – through repeated findings showing an association (those good solid, old fashioned science standards of replicability and verification). It is only by eliminating other potential associations – variables – that we can establish causalities.

The objective of a lot of research or scientific analysis is to identify the extent to which one variable relates to another variable. If there is a correlation then this guides further research into investigating whether one action causes the other. Statistics measure occurrences in time and can be used to calculate probabilities. Probability is important in studies and research because measurements, observations and findings are often influenced by variation. In addition, probability theory provides the theoretical groundwork for statistical inference.

Statistics are fundamental to good government, to the delivery of public services and to decision-making at all levels of society. Statistics provide parliament and the public with a window on the work and performance of a government. Such data allows for the design of policies and programs that aim to bring about a desired outcome, and permits better targeting of resources. Once a policy has been implemented it is necessary to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the policy to determine whether it has been successful in achieving the intended outcomes. It is also important to evaluate whether services (outputs) are effectively reaching those people for whom they are intended. Statistics play a crucial role in this process. So statistics, therefore, represent a significant role in good policy making and monitoring. The impact of policy can be measured with statistics.

So firstly, we need to ask why the government are not doing this.

If policy impacts cannot be measured then it is not good policy.

Ensuring accuracy and integrity in the reporting of statistics is a serious responsibility. In cases where there may not be an in-depth understanding of statistics in general, or of a particular topic, the use of glossaries, explanatory notes and classifications ought to be used to assist in their interpretation.

Statistics can be presented and used in ways that may lead readers and politicians to draw misleading conclusions. It is possible to take numbers out of context, as Iain Duncan Smith, amongst others, is prone to do. However, official statistics are supposed to be produced impartially and free from political influence, according to a strict code of practice. This is a government that systematically breaches the code of conduct. See: List of official rebukes for Tory lies and statistical misrepresentations, for example

We need to ask why the government refuses to conduct any research into their austerity policies, the impact they are having and the associated deaths and suicides.

Without such research, it isn’t appropriate or legitimate to deny a causal link between what are, after all, extremely punitive, targeted, class contingent policies and an increase in premature mortality rates.

The merits of qualitative research

However, I believe that social phenomena cannot always be studied in the same way as natural phenomena. There are, for example, distinctions to be made between facts and meanings. Qualitative researchers are concerned with generating explanations and extending understanding rather than simply describing and measuring social phenomena and establishing basic cause and effect relationships. Qualitative research tends to be exploratory, potentially illuminating underlying intentions, reasons, opinions, and motivations to human behaviours. It often provides insight into problems, helps to develop ideas, and may also be provide potential for the formulation hypotheses for further quantitative research.

The dichotomy between quantitative and qualitative methodological approaches, theoretical structuralism (macro-level perspectives) and interpretivism (micro-level perspectives) in sociology, for example, is not nearly so clear as it once was, however, with many social researchers recognising the value of both means of data collection and employing methodological triangulation, reflecting a commitment to methodological and epistemological pluralism. Qualitative methods tend to be much more inclusive, lending participants a dialogic, democratic voice regarding their experiences.

The government have tended to dismiss qualitative evidence of the negative impacts of their policies – presented cases studies, individual accounts and ethnographies – as “anecdotal.”

However, such an approach to research potentially provides insight, depth and rich detail because it explores beneath surface appearances, delving deeper than the simplistic analysis of ranks, categories and counts. It provides a reliable record of experiences, attitudes, feelings and behaviours and prompts an openness that quantitative methods tend to limit, as it encourages people to expand on their responses and may then open up new topic areas not initially considered by researchers. As such, qualitative methods bypass problems regarding potential power imbalances between the researcher and the subjects of research, by permitting participation and creating space for genuine dialogue and reasoned discussions to take place. Research regarding political issues and impacts must surely engage citizens on a democratic basis and allow participation in decision-making, to ensure an appropriate balance of power between citizens and government.

That assumes of course that governments want citizens to engage and participate. There is nothing to prevent a government deliberately exploiting a research framework as a way to test out highly unethical and ideologically-driven policies, and to avoid democratic accountability, transparency and safeguards. How appropriate is it to apply a biomedical model of prescribed policy “treatments” to people experiencing politically and structurally generated social problems, such as unemployment, inequality and poverty, for example?

Conservative governments are indifferent to fundamental public needs

The correlation between Conservative policies and an increase in suicides and premature deaths is a fairly well-established one.

For example, Australian social scientists found the suicide rate in the country increased significantly when a Conservative government was in power.

And an analysis of figures in the UK strongly suggests a similar trend.

The authors of the studies argue that Conservative admininistration traditionally implies a less supportive, interventionist and more market-orientated policy than a Labour one. This may make people feel more detached from society, they added. It also means support tends to be cut to those who need it the most.

Lead researcher Professor Richard Taylor, of the University of Sydney, told BBC News Online:

“We think that it may be because material conditions in lower socio-economic groups may be relatively better under labour because of government programmes, and there may be a perception of greater hope by these groups under labour.

There is a strong relationship between socio-economic status and suicide.”

The research is published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

In one of a series of accompanying editorials, Dr Mary Shaw and colleagues from the University of Bristol say the same patterns were evident in England and Wales between 1901 and 2000.

Rates have been lower under Labour governments and soared under the last Conservative regime, which began in 1979 under Margaret Thatcher.

Interestingly, the authors of more recent research point out that although suicide rates tend to increase when unemployment is high, they were also above average during the 1950s when Britain “never had it so good,” but was ruled by the Conservative party.

Overall, they say, the figures suggest that 35,000 people would not have died had the Conservatives not been in power, equivalent to one suicide for every day of the 20th century or two for every day that the Conservatives ruled.

The UK Conservative Party typically refused to comment on the research.

Not a transparent, accountable and democratic government, then.

More recently, public health experts from Durham University have denounced the impact of Margaret Thatcher’s policies on the wellbeing of the British public in research which examines social and health inequality in the 1980s.

The study, which looked at over 70 existing research papers, concludes that as a result of unnecessary unemployment, welfare cuts and damaging housing policies, the former prime minister’s legacy includes the unnecessary and unjust premature death of many British citizens, together with a substantial and continuing burden of suffering and loss of well-being.

The research shows that there was a massive increase in income inequality under Baroness Thatcher – the richest 0.01 per cent of society had 28 times the mean national average income in 1978 but 70 times the average in 1990, and UK poverty rates went up from 6.7 per cent in 1975 to 12 per cent in 1985.

Thatcher’s governments wilfully engineered an economic catastrophe across large parts of Britain by dismantling traditional industries such as coal and steel in order to undermine the power of working class organisations, say the researchers. They suggest this ultimately fed through into growing regional disparities in health standards and life expectancy, as well as greatly increased inequalities between the richest and poorest in society.

Co-author Professor Clare Bambra from the Wolfson Research Institute for Health and Wellbeing at Durham University, commented:

“Our paper shows the importance of politics and of the decisions of governments and politicians in driving health inequalities and population health. Advancements in public health will be limited if governments continue to pursue neoliberal economic policies – such as the current welfare state cuts being carried out under the guise of austerity.”

Housing and welfare changes are also highlighted in the paper, with policies to sell off council housing such as Right to Buy scheme and to reduce welfare payments resulting in further inequalities and causing “a mushrooming of homelessness due to a chronic shortage of affordable social housing.” Homeless households in England tripled during the 1980s from around 55,000 in 1980 to 165,000 in 1990.

And while the NHS was relatively untouched, the authors point to policy changes in healthcare such as outsourcing hospital cleaners, which removed “a friendly, reassuring presence” from hospital wards, led to increases in hospital acquired infections, and laid the ground for further privatisation under the future Coalition government.

The figures analysed as part of the research also show high levels of alcohol and drug-related mortality and a rise in deaths from violence and suicide as evidence of health problems caused by rising inequality during the Thatcher era.

The study, carried out by the Universities of Liverpool, Durham, West of Scotland, Glasgow and Edinburgh, is published in the International Journal of Health Services. It was scientifically peer-reviewed and the data upon which it was based came from more than 70 other academic papers as well as publicly available data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The Government has repeatedly denied any links between social security cuts and deaths, despite the fact that there is mounting and strong evidence to the contrary. Yet it emerged that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has carried out 60 reviews into deaths linked to benefit cuts in the past three years.

The information, released by John Pring, a journalist who runs the Disability News Service (DNS), was obtained through Freedom of Information requests. The data showed there have been 60 investigations into the deaths of benefit claimants since February 2012.

The DWP says the investigations are “peer reviews following the death of a customer.”

Iain Duncan Smith has denied that this review happened:

“No, we have not carried out a review […] you cannot make allegations about individual cases, in tragic cases where obviously things go badly wrong, you can’t suddenly say this is directly as a result of government policy.”

Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, 5 May 2015.

Several disability rights groups and individual campaigners, including myself, have submitted evidence regularly to the United Nations over the past three years, including details of Conservative policies, decision-making narratives and the impact of those policies on sick and disabled people. This collective action has triggered a welcomed international level investigation, which I reported last August: UK becomes the first country to face a UN inquiry into disability rights violations.

The United Nations only launch an inquiry where there is evidence of “grave or systemic violations” of the rights of disabled people.

Government policies are expressed political intentions regarding how our society is organised and governed. They have calculated social and economic aims and consequences.

How policies are justified is increasingly being detached from their aims and consequences, partly because democratic processes and basic human rights are being disassembled or side-stepped, and partly because the government employs the widespread use of propaganda to intentionally divert us from their aims and the consequences of their ideologically (rather than rationally) driven policies. All bullies and despots scapegoat and stigmatise their victims. Furthermore, policies have become increasingly detached from public interests and needs.

It’s possible to identify which social groups this government are letting down and harming the most – it’s the ones that are being politically marginalised and socially excluded. It’s those groups that are scapegoated and deliberately stigmatised by the perpetrators of their misery.

Iain Duncan Smith and Priti Patel claim that we cannot make a link between government policies and the deaths of some sick and disabled people. There are no grounds whatsoever for that claim. There has been no cumulative impact assessment, no inquiry, no further research regarding an established correlation and a longstanding refusal from the Tories to undertake any of these. There is therefore no evidence for their claim.

Political denial is repressive, it sidesteps democratic accountability and stifles essential debate and obscures evidence. Denial of causality does not reduce the probability of it, especially in cases where a correlation has been well-established and evidenced.

This is Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation and Power. Whereabouts are we?

For Arnstein, participation reflects “the redistribution of power that enables the have-not citizens, presently excluded from the political and economic processes, to be deliberately included in the future. It is the strategy by which the excluded join in determining how information is shared, goals and policies are set, tax resources are allocated, programmess are operated, and benefits like contracts and patronage are parceled out. In short, it is the means by which they can induce significant social reform which enables them to share in the benefits of the affluent society.”

A starting point may be the collective gathering of evidence and continual documentation of our individual experiences of austerity and the welfare “reforms”, which we must continue to present to relevant ministers, parliament, government departments, the mainstream media and any organisations that may be interested in promoting citizen inclusion, empowerment and democratic participation.

We can give our own meaningful account of our own experiences and include our own voice, reflecting our own first-hand knowledge of policy impacts, describing how we make sense of and understand our own situations, including the causal links between our own circumstances, hardships, sense of isolation and distress, and Conservative policies, as active, intentional, consciencious citizens. Furthermore, we can collectively demand a democratic account and response (rather than accepting denial) from the government.

—

Related

A tale of two suicides and a very undemocratic, inconsistent government

The Tories are epistemological fascists: about the DWP’s Mortality Statistics release

The DWP mortality statistics: facts, values and Conservative concept control

Pictures courtesy of Robert Livingstone

I don’t make any money from my work. I am disabled because of illness and have a very limited income. But you can help by making a donation to help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.