In this paper, Michael Adler, Emeritus Professor of Socio-Legal Studies, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh, highlights the enormous growth in the severity, the scope and the incidence of benefit sanctions in the UK since the turn of the century, and assesses the compatibility of the current sanctions regime with the ‘rule of law’.

This blog is based on a paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Law Society of Scotland, held at the Edinburgh International Conference Centre on 2nd October 2015. The author is very grateful to David Webster, Jeff King and Colm O’Cinneide for their help.

Few people have written as clearly on the ‘rule of law’ as Tom Bingham, formerly Master of the Rolls, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, and Senior Law Lord in the UK Supreme Court, and I use his analysis as my starting point. According to Tom Bingham,[1] the ‘rule of law’ comprises eight principles. These are set out in Table 1 below:

Table 1: The eight principles of the Rule of Law

| 1. | The law must be accessible and, so far as possible, intelligible, clear and predictable. |

| 2. | Questions of legal right and liability should ordinarily be resolved by application of the law and not of discretion. |

| 3. | The laws of the land should apply equally to all, save to the extent that objective differences justify differentiation. |

| 4. | Ministers and public officials at all levels must exercise the powers conferred on them in good faith, fairly for the purpose for which the powers were conferred, without exceeding the limits of such powers and not unreasonably. |

| 5. | The law must offer adequate protection of fundamental human rights. |

| 6. | Means must be provided for resolving, without prohibitive cost or inordinate delay, bona fide civil disputes which the parties themselves are unable to resolve. |

| 7. | Adjudicative procedures provided by the state should be fair. |

| 8. | The rule of law requires compliance by the state of its obligations in international law as in national law. |

Since few members of the audience will have any personal experience of sanctions and most of you will probably only be dimly aware of their existence, the paper starts with an account of recent changes in the sanctions regime.

The origins of benefit sanctions

There is nothing new about benefit sanctions. When unemployment insurance was introduced in the UK under the National Insurance Act 1911, claimants could be disqualified from benefit for periods of up to six weeks for a limited number of reasons (mainly for having left work voluntarily, lost their job as a result of ‘misconduct’ or not being available for work). What is new is the striking increase in their scope and severity, and in their incidence. Most of these changes can be traced back to the Jobseeker’s Act 1995, which inserted the principle of ‘activation’ into social security for those deemed capable of work (or of progression towards it), made the receipt of benefit conditional on claimants’ job-seeking behaviour, required claimants to undertake training and job-search, and introduced sanctions for non-compliance.

THE increasing scope and severity of benefit sanctions

Benefit sanctions are now very much wider in scope (in that they are applied to more misdemeanours), greater in severity (in that they apply for longer periods) and more extensive in application (in that they apply to more people) than was formerly the case.

The main changes in the scope and severity of benefit sanctions since the 1980s are summarised in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Benefit Sanctions Then and Now

| THEN (pre-activation) | NOW (post-activation) |

| only passive ‒ mainly for ex-ante offences e.g. leaving work voluntarily, losing their job as a result of ‘misconduct’ or not being available for work | also active ‒ mainly for ex-post offences, e.g. not ‘actively seeking work’, failure to participate in a training or employment scheme and missing an interview |

| applied to unemployed | also apply to single parents and long-term sick and disabled people |

| applied to applicants for insurance benefits | apply to applicants for all the main out-of-work benefits |

| applied for up to 6 weeks (1911-1986), 13 weeks (1986-1988) or 26 weeks (1988 onwards) | now apply for up to 156 weeks (three years) |

| sanctioned claimants had a right to claim means-tested social assistance (at a reduced rate) immediately | sanctioned claimants can apply for discretionary ‘hardship payments’ but, in many cases, only after a two week delay |

The increasing incidence of benefit sanctions

In 2001, about 300,000 sanctions and disallowances were imposed by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) on JSA claimants. This figure remained fairly static for the next five years but started to rise quite sharply in 2006 and exceeded 1 million in 2013. Thus, the increase over the period was nearly 250 per cent. The number of sanctions fell to just over 700,000 in 2014, mainly because of the decline in unemployment and the corresponding reduction in the JSA caseload, which fell by about 30 per cent. However, this is more than twice the number imposed in 2001.

In addition to JSA sanctions, 34,000 sanctions were imposed on ESA claimants in 2013. The detailed statistics for sanctions and disqualifications are set out in Table 3 below.

Table 3: JSA and ESA Sanctions and Disqualifications, 2000-2014

| Year | Number of JSA sanctions imposed | Change since 2001 (%) [see note below] | Number of ESA sanctions imposed |

| 2000 | no statistics available | ||

| 2001 | 300,104 | ||

| 2002 | 305,080 | +1.65% | |

| 2003 | 282,096 | -6.00% | |

| 2004 | 258,985 | -13.70% | |

| 2005 | 267,172 | -10.93% | |

| 2006 | 278,827 | -7.09% | |

| 2007 | 351,341 | +17.07% | |

| 2008 | 380,028 | +26.63% | |

| 2009 | 471,476 | +57.10% | 19,087 |

| 2010 | 742,030 | +147.26% | 30,298 |

| 2011 | 738,850 | +146.20% | 4,817 |

| 2012 | 904,965 | +201.55% | 14,361 |

| 2013 | 1,046,398 | +248.67% | 34,022 |

| 2014 | 702,000 | +133.92% | 36,808 |

Note: 2001 was selected as the base year for comparisons because the statistical system changed in that year.

Source: The statistics are based on the DWP’s quarterly sanctions statistics, published in Jobseeker’s Allowance and Employment and Support Allowance sanctions and available at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/jobseekers-allowance-and-employment-and-support-allowance-sanctions-decisions-made-to-june-2014

Comparing benefit sanctions with court fines

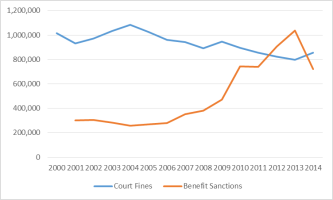

To put these figures into perspective, we can compare changes in the number of benefit sanctions with changes in the number of fines imposed in the criminal courts in the period since 2000. While the incidence of benefit sanctions in Great Britain increased from about 300,000 to more than 1,000,000 over the period 2001-2013, the incidence of fines imposed in the criminal courts in England and Wales decreased from about 1,000,000 to about 800,000. Although it is not generally known, the incidence of benefit sanctions overtook the number of court fines in 2012. The gap opened up in 2013 but the number of benefit sanctions fell quite sharply in 2014, due mainly to a fall in the number of unemployed people. However, the number of benefit sanctions is still very high indeed. These changes are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Incidence of Criminal Fines and Benefit Sanctions 2000-2014

Court fines are preceded by court proceedings and these provide a reasonable level of procedural protection. They are set at ‘moderate levels’ but, because judges impose fines without inquiring into offenders’ circumstances or ability to pay, and because many offenders are unemployed and/or poor, the extent of proportionality in imposing fines is not all that high. Fine default is quite a serious problem and, although it is being tackled, a few fine defaulters still end up in prison. The imposition of court fines is not, in principle, inconsistent with justice although the justice inherent in the process could be enhanced.

Benefit sanctions are not preceded by legal proceedings. There are established reconsideration and appeal procedures although, since there are no time limits, reconsideration can take a long time and sanctions are implemented without waiting for claimants’ cases to be considered. The number of appeals to an independent tribunal increased by more than 600 per cent over the period but Mandatory Reconsideration (MR), which was introduced in 2013, was designed to choke this off and appears to have done so. The number of appeals in the three month period October-December 2012 fell from 130,606 to 28,142 in the same period two years later, i.e. in 2014.

Until October 2013, when MR was introduced, claimants could either ask for the DWP’s decision to impose a sanction to be reviewed, in which case, this would be undertaken by a different decision maker, or they could appeal directly to a tribunal. Now they must first make an informal request for reconsideration (there is no form). The claimant is then telephoned by the original decision-maker and given a verbal ‘explanation’ or, on request, a written statement of reasons (WSOR), and may be given an opportunity to provide further information relevant to the decision. If the claimant accepts this explanation, the matter ends there. However, if the claimant disputes anything, the initial decision-maker will consider what they have to say, including any new evidence they present. The initial decision-maker may change his/her decision at this point but, if not, and the claimant insists, the initial decision maker (not the claimant) will request a formal Mandatory Reconsideration (MR), which is undertaken by a new, remotely-located Dispute Resolution Team (DRT), and only if they are turned down at this stage can they appeal to a tribunal. Claimants who wish to appeal must submit an application to HM Courts and Tribunals Service within one month of the date on which they were given the result of Mandatory Reconsideration. It is hardly surprising that the numbers of reviews and appeals have plummeted.

Thus, the combination of internal review and external appeal procedures does not provide an acceptable level of procedural protection. Those who receive benefit sanctions are, because they were on benefit and have had their benefit stopped, among the poorest people in society and the sanctions themselves are extremely severe since they can deprive claimants of all their income for periods ranging from four weeks to three years. If the courts were to impose fines set at the level of the offender’s disposable income, and go on doing this for lengthy periods, there would be an outcry. Sanctions for a non-criminal offence that are set at 100 per cent of the alleged offender’s income and applied repeatedly are, clearly, totally lacking in proportionality.

Vulnerable claimants are most likely to be sanctioned and, despite the availability of hardship payments, many of those who are sanctioned experience enormous hardship. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many of them end up becoming homeless, using food banks and resorting to crime. It is hard to see how these shortcomings could be rectified and it follows that benefit sanctions, as they have developed in the UK, are incompatible with justice. salient characteristics of court fines and benefit sanctions are compared in Table 4.

Table 4. The salient characteristics of court fines and benefit sanctions

We now come to the question of whether benefit sanctions are compatible with the rule of law. My conclusions, and I must stress that these are my personal conclusions and that other people may wish to take issue with them, is that they are not. The consistency of benefit sanctions with Bingham’s eight principles is summarised in Table 5 and discussed in more detail below.

Table 5: Benefit Sanctions and the eight principles of the Rule of Law

| Principle | Assessment | Compliance |

| 1 | unclear whether the law is either accessible or intelligible, clear and predictable | doubtful |

| 2 | most decisions involve discretion, disputes are handled internally and adjudication is rare | no |

| 3 | sanctions apply to everyone in receipt of benefits | yes |

| 4 | sanctions are often applied unreasonably and for trivial misdemeanours | no |

| 5 | the right to a fair trial, guaranteed under Art. 6, is inadequately protected | no |

| 6 | appeals to tribunals have virtually disappeared | no |

| 7 | MR procedures weighted against claimants | no |

| 8 | international law does not apply | no |

- Although the Decision Makers’ Guide provides guidance for DWP staff who make decisions about benefits and pensions and helps them make decisions that are accurate and consistent, claimants have not been provided with any comparable account of the law which sets out when sanctions can be imposed and how they can be challenged. However, since October 2013, new jobseekers have been required to sign a ‘Jobseekers’ Agreement’, which sets out what they need to do in order to receive state support, and they will have to renew this on a regular basis. They also have to provide evidence to prove they have met the requirements in their Jobseekers’ Agreement or a Jobseekers’ Direction, which specifies exactly what they are required to do, and those who fail to do so ‘without good reason’ risk losing their benefits. Although this is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, there must be very real doubts about whether the first principle is satisfied.

- The phrase ‘good reason’ is not defined in the legislation and depends on the circumstances of the case. Most disputes involve the exercise of discretion and are handled internally while independent adjudication is only used in the very small number of cases that are appealed to a tribunal. Whether this is sufficient to satisfy the second principle is an open question.

- Since the sanctions regime applies to everyone in receipt of benefits, the third principle appears to be satisfied.

- There is an accumulating body of evidence that sanctions are often applied unreasonably and for trivial misdemeanours. In addition, the absence of comprehensive quality assurance procedures and the failure to hold individual members of staff who have acted unfairly or unreasonably to account for their decisions, even where these overturned as a result of review or appeal, raise serious doubts about whether the fourth principle is satisfied.

- The attenuated arrangements for challenging the imposition of sanctions, which can leave people without any income, indicate that the right to a fair trial, guaranteed under Article 6 of the ECHR, it is inadequately protected. This suggests that the fifth principle is probably not satisfied.

- Cost is not an issue since there are no financial barriers to challenging the DWP’s decision to impose a sanction but delay is, mainly because there are no time limits for the DWP to reconsider its decision As a result, a claimant who wishes to challenge the imposition of a sanction may have to endure a long period without any income. Under MR, so many obstacles have been put in the way of getting to an independent Tribunal that Tribunal appeals have virtually disappeared; the right of appeal has become effectively purely theoretical. This indicates that the sixth principle is also probably not satisfied.

- The adjudicative procedures provided by the state in tribunals that hear appeals are undoubtedly fair. However, the MR process which is now the last recourse for almost all claimants is clearly unfair as it is completely one-sided. Moreover, the difficulty that claimants experience in accessing these procedures raises doubts about the fairness of the whole set of procedures for challenging sanctions. Thus, the seventh principle is also probably not satisfied.

- Benefit sanctions probably violate the International Covenant on Social and Cultural Rights. In addition, although Article 13 of the European Social Charter permits benefit sanctions, they must not deprive the person concerned of his/her means of subsistence. The situation in the UK is currently under review but, on these grounds, the eighth principle is also probably not satisfied.

The number of counts on which the current sanctions regime in the UK fails to satisfy the rule of law principles proposed by Lord Bingham indicate that there are serious questions about its legality ‒ in addition to its efficacy and humanity.

The most significant reform, which would undoubtedly make the sanctions regime more consistent with the rule of law, would involve giving claimants an opportunity to attend a hearing before a sanction is imposed (as is the case in in the USA) and continuing to pay benefit until the hearing has taken place. Another significant reform would involve abolition of the Mandatory Reconsideration procedure. Claimants who wished to challenge the imposition of a sanction would appeal directly to a tribunal. Cases could be reconsidered by the DWP before the hearing but, if the claimant’s case was not met in full, the appeal would then be heard by the tribunal. A further reform would involve reducing the severity of the sanctions that are imposed. In addition, some serious thought also needs to be given to reducing the scope of conditionality so that fewer sanctions are imposed in the first place. Unfortunately, given its commitment to conditionality and sanctions, it is most unlikely that any of these reforms will be accepted by the UK Government.

Minor reforms, such as issuing written statements of what claimants can expect from staff as well as what staff expect from claimants that would explain what the consequences for each party of failing to meet the expectations of the other are, and giving claimants a right to seek a review of these statements and to appeal against them to a tribunal, would help to make the administration of benefits fairer and more humane, as would strengthening the provision of hardship payments for those who are sanctioned. However, the prospect of minor reforms such as these being supported by the UK Government is, to say the least, unlikely.

In a recent Report, the House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee (2015) reiterated its previous call for a comprehensive, independent review of sanctions and for a serious attempt to resolve the conflicting demands on claimants made by DWP staff to enable them to take a common-sense view on good reasons for non-compliance. The Committee concluded that there was no evidence to support the longer sanction periods introduced in October 2012 and recommended the piloting of pre-sanction written warnings and non-financial sanctions. Sadly, these recommendations seem to have fallen on deaf ears and to date there has been no response from the DWP to the Report.

[1] Bingham, Tom (2010) The Rule of Law, London: Allen Lane.

You can read the original article here

For more about the origins of the extended use of sanctions, see here

Skimmed over the first words. It has given me the urge to read it Kittsyjones 😀

Thank you ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on perfectlyfadeddelusions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is often said that “No Person Is above the Law” so why is the Government above the law, I say this as the report mentions that the DWP were to make a response to the meaning of the Law and Civil Rights where people have no means of gaining any Hearing Proper. In the secular world and The Government were to request information for any circumstance and the Proprietor or Directors failed to respond the Government would make an enforcement for those concerned to repond or face charges of Perverting the course of Justice, so in this case, this application should be made against the Government and it’s departments who have failed to respond to a Civil Request just as the Secular System would have to. By this not happening it is proving to be fascism with no law at all for any person apart from Government decisions of what they wish to do and make others comply without any justification why.

LikeLiked by 1 person