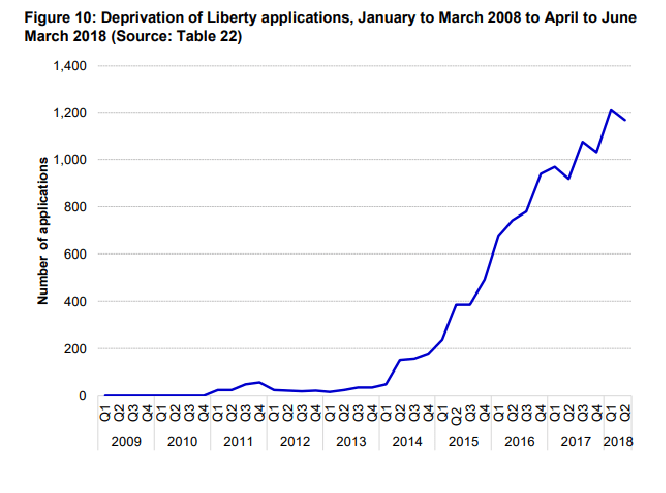

Under the Conservative government, applications for the Deprivation of Liberty of citizens have soared. (Source: Court of Protection hub.)

In 2014, a Supreme Court judgment significantly widened the definition of deprivation of liberty, meaning more people were subsequently considered to have their liberty deprived. There was a ten-fold increase in the number of deprivation of liberty applications following the judgment. Services struggled to cope, deadlines were “routinely breached” and the Law Commission decided that the system should be replaced.

Law Commissioner Nicolas Paines QC said the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards were designed at a time when fewer people were considered deprived of their liberty and now it was “failing” people it was set up to protect.

“It’s not right that people with dementia and learning disabilities are being denied their freedoms unlawfully,” he said.

“There are unnecessary costs and backlogs at every turn, and all too often family members are left without the support they need.”

Over the last eighteen months, the Law Commission – a statutory independent body created by the Law Commissions Act 1965 to keep the law of England and Wales under review and to recommend reform where it is needed – has been reviewing the framework that is called Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLs) which is put in place when a person who lacks capacity is placed in a care home.

Deprivation of Liberty, which is defined in part of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, is there to ensure that there are checks and balances for the person placed in care, that decisions are made in their best interest and that an independent advocate can be appointed to speak on their behalf in these decision making processes.

The Commission made recommendations to change the law, following public consultation. The recommendations included:

- Enhanced rights to advocacy and periodic checks on the care or treatment arrangements for those most in need.

- Greater prominence given to issues of the person’s human rights, and of whether a deprivation of their liberty is necessary and proportionate, at the stage at which arrangements are being devised.

- Extending protections to all care settings, such as supported living and domestic settings, therefore removing the need for costly and impractical applications to the Court of Protection.

- Widening the scope to cover 16 and 17 year olds and planned moves between settings.

- Cutting unnecessary duplication by taking into account previous assessments, enabling authorisations to cover more than one setting and allowing renewals for those with long-term conditions.

- Extending who is responsible for giving authorisations from councils to the NHS if in a hospital or NHS healthcare setting.

- A simplified version of the best interests assessment, which emphasises that, in all cases, arrangements must be necessary and proportionate before they can be authorised.

However, the Law Commission recognised that many people who need to be deprived of their liberty at home benefit from the loving support that close family can provide. These reforms, which aimed to widen protections to include care or treatment in the home, were designed to ensure that safeguards can be provided in a simple and unobtrusive manner, which minimises distress for family carers.

Importantly, the Commission also recommended a wider set of reforms which would improve decision making across the Mental Capacity Act. This is not just in relation to people deprived of liberty. All decision makers would be required to place greater weight on the person’s wishes and feelings when making decisions under the Act.

Professionals would also be expected to confirm in writing that they have complied with the requirements of the Mental Capacity Act when making important decisions – such as moving a person into a care home or providing (or withholding) serious medical treatment.

The government responded and put forward proposals for changing the Mental Capacity Act. However, though this new legislation has been worded carefully, its effect will be to risk the removal of key human rights; it also ignores the entire concept of best interests and has put decision making power over people’s liberty and rights in the hands of organisations and their managers with a commercial interest in decisions and outcomes.

Any statutory scheme which permits the state to deprive someone of their liberty for the purpose of providing care and treatment must be comprehensible, with robust safeguards to ensure that human rights are observed.

In July 2018, the government published the Mental Capacity (Amendment) Bill, which if passed into law, will reform the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS), and replace them with a scheme known as the Liberty Protection Safeguards (although the term is not used in the Bill itself).

The Bill draws on the Law Commission’s proposals for reforming DoLS, but generally does not address some of the wider Mental Capacity Act reforms that the Law Commission suggested. Proposed reforms around supported decision making and best interests are not included, for example, and these omissions are very controversial.

In a statement accompanying the proposals the government claims that £200m per year will be saved by local authorities under the new scheme, though the increased role of the NHS and independent sector providers will lead to increased costs elsewhere.

The new responsibilities being imposed on care homes, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and hospitals will need some thought, resources and training.

Members of the House of Lords have already warned that the Bill to reform the law on deprivation of liberty does not adequately secure the rights of people subject to restrictive care arrangements. In Parliament’s first debate on the Mental Capacity (Amendment) Bill on 16 May this year, peers questioned several elements of the legislation.

The Liberty Protection Safeguards are designed to provide a much less bureaucratic system than DoLS for authorising health and social care arrangements that involve a deprivation of liberty to which a person cannot consent.

The proposed Bill has been widely criticised because it contains insufficient safeguards and is not fit for purpose in its current form. It requires serious reconsideration and extensive revision.

The vast majority of both home care and residential care in England is now provided by private companies. Both the quality of care in adult social care and the terms and conditions of the workforce have declined over the past two decades as a result of privatisation.

The Department of Health’s review of Adult Social Care in 2015/16 discussed the introduction of red tape reduction options in non-statutory areas of DoLS applications, in the private sector, and concluded that these had been ‘exhausted’.

The review report (page 30) says: “As such, the Department has funded the Law Commission (as the experts in law reform) to perform a fundamental review of DoLS “with a view to minimising pressures on care providers.”

That must not come at the expense of safeguarding adults from exploitation for private profit.

In October 2017, the Prime Minister also commissioned a review of the Mental Health Act 1983, seeking to address concerns about how the legislation is currently being used.

The government called for an Act in step with a ‘modern mental health system’, giving special attention to rising rates of detention and the disproportionate number of people from black and minority ethnic backgrounds being detained under the Act. Terms of reference for the review are available to view online. The review was tasked to appraise existing practice and evidence, formulating recommendations to improve legislation and/or practice in the future.

The chair of the review is Simon Wessely. He said “The Mental Health Act goes to the core of the relationship between the individual and the state.

“It poses the question: ‘When is it legitimate to deprive someone of their liberty, even when they have done nothing wrong?’ It sets rules that require professionals to judge if a mentally ill person poses a risk to themselves or others, and hence needs to be detained in order to safely receive treatment. It tries to strike a fair bargain with the detained person, giving them safeguards like second opinions and tribunals to ensure due process.

“Reviewing the Act isn’t just about changing the legislation. In some ways that might be the easy part. The bigger challenge is changing the way we deliver care so that people do not need to be detained in the first place. In my experience it is unusual for a detention to be unnecessary – by the time we get to that stage people are often very unwell, and there seems few other alternatives available.

“But that does not mean this was not preventable or avoidable. The solutions might lie with changes to the legislation, but could also come from changes in the way we organise and deliver services. It would also be naïve to deny that much wider factors, such as discrimination, poverty and prejudice, could be playing a role.”

Wessely said his final report will make recommendations that require ‘significant’ new investment in the sector. However the government is looking to save money.

Wessely has played a notorious key role in the demedicalisation of myalgicencephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) research. Serving as an advisor to the hugely controversial PACE trial, Wessely has defended the study of these illnesses, and the proposed treatment regime of CBT and graded exercise, stating “this trial was a landmark in behavioral complex intervention studies.” Wessley’s purely psychological approach to these physiological illnesses has been widely criticised, he has been accused of “unsupported conclusions derived from faulty analyses.”

In 1988 the public water supply in Camelford in England was accidentally contaminated with aluminium sulfate. Wessely published a paper in 1995 playing down the effects of the pollution and suggesting ‘significant psychological factors’ were involved. The government formally and unreservedly apologised in 2013, 25 years later, to those whose health was affected by the water supply contamination.

Things Wessley has said about ME/CFS include “The worst thing to do is tell them to rest”, “exercise is good for these patients” and “[Welfare] Benefits can often make patients worse”. See Notes on the involvement of Wessely et al with the Insurance

Industry and how they deal with ME/CFS claims .

I’m not confident that either the stated aims or in the outcome of this ‘independent’ review. The government have already amended the Mental Capacity Act, removing Practice Direction 9, which provided safeguards for people with degenerative illnesses and brain injury in the event of the proposed withdrawal of nutrition and hydration by doctors (See British Medical Association proposals deemed passive ‘euthanasia by stealth’ for disabled people with degenerative illnesses).

See also: Independent review of the Mental Health Act: interim report.

The Law Society’s condemnation of the government’s Mental Capacity (Amendment) Bill 2018

The Law Society has issued a rather damning briefing on the Mental Capacity (Amendment) Bill 2018 that moved to a Lords committee stage in early September.

The Society says that the Bill is not fit for purpose: “While agreeing that simplification is needed and acknowledging that there are resource constraints, these constraints are “insufficient justification for not implementing fully the safeguards recommended by the Law Commission.”

The Briefing also sets out six recommendations for change, reflecting what the authors feel should be the principles underpinning the new framework and why they are concerned that the Bill does not meet those principles, as it includes:

- an already overly complex scheme being further complicated by a replacement scheme which instead of placing the cared-for person at the centre of the process, significantly dilutes and even removes the existing protections for them

- the risk of increased burdens on local authorities who will bear ultimate responsibility for mistakes and poor implementation rather than building on the learning from the problems with DoLS and retaining those elements that have been effective whilst removing those which are unnecessary and bureaucratic

- the cared-for person will not be at the centre of the process but side-lined with decisions being made without proper or even basic protections

- the removal of the invaluable role of Best Interests Assessors and Relevant Person’s Representatives would leave vulnerable people without protection from unnecessary detention.

You can read the Law Society’s full Briefing here: Parliamentary briefing: Mental Capacity (Amendment) Bill – House of Lords committee stage (PDF 196kb).

Junior health and social care minister Lord O’Shaughnessy opened the debate at the Bill’s second reading in the House of Lords by saying the Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS) would be less burdensome than DoLS on people, carers and local authorities, saving the latter an estimated £160m a year.

He said it would do this by making consideration of restrictions on people’s liberties a part of their overall care planning and eliminating repeat assessments and authorizations. However, peers from across the House of Lords agreed that several aspects of the bill risked weakening safeguards for people deprived of their liberty.

Labour peer Lord Touhig, vice-president of the National Autistic Society (NAS), voiced concerns about the rights of autistic people under the bill’s proposals, insisting that many of the problems with the existing system had not been addressed.

He cited, as particularly problematic, the removal of the best interests assessment currently provided under DoLS, which ensures that arrangements to deprive a person of their liberty are in the individual’s best interests, necessary to protect them from harm and proportionate to the likelihood and seriousness of that harm.

Under the LPS, the equivalent requirement would be to establish that the arrangements are ‘necessary and proportionate’, one of three criteria that must be met for a LPS authorisation, the others being that the person lacks capacity to consent and is of ‘unsound mind’.

Touhig said: “The new criteria risk losing sight of what is best for the individual and what the individual wants.

“Let us be wary of enacting legislation that pays scant regard to the individual, in particular an individual who is perhaps the most vulnerable in society.”

Liberal Democrat peer Baroness Barker highlighted problems with the ability of bodies authorising LPS arrangements to rely on historic assessments of mental capacity, which may have been carried out for other purposes.

She said: “There is a danger that we might end up with decisions being made about a person’s capacity to make one decision which rests on information that was gathered for a wholly different purpose. That would not be right.”

Under the new title, ‘Liberty Protection Safeguards,’ the proposals mean that the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguard is removed from the Mental Capacity Act 2005, with a new administrative scheme for authorising arrangements when it comes to the deprivation of liberty.

In the Bill it says that the person responsible for decision making should ‘reasonably believe’, action to deprive someone of liberty is necessary to prevent ‘serious deterioration.’ One problem is that there is no guarantee in place that ensures a sharp focus on ensuring decisions are made in the best interest of vulnerable individuals. It is also important to ensure the new legislation allows for deprivation of liberty to be a very last resort.

There is also nothing in the Bill that explores what training will be made available to acting mental capacity professionals and where the costs of this will fall.

While the new system aims to remove the problems associated with getting authorisation when moving between a care home and hospital setting will be welcomed, whether this places new pressures on the sector will also need some consideration. It is therefore expected that the debate will consider the cost of new arrangements, with close attention being paid to the £200m a year the government project the system will save local authorities.

The government’s recent amendment is regressive and the changes, instead of looking after people’s best interests, appear to have become a cost-cutting exercise that can only lead to people’s human rights being removed.

In summary, key features of the Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS) include:

- Like DoLS (but contrary to the Law Commission’s suggestion) they start at 18. There is no statutory definition of a deprivation of liberty beyond that in the Cheshire West and Surrey Supreme Court judgement of March 2014 – the acid test.

- Deprivations of liberty have to be authorised in advance by the ‘responsible body’

- For hospitals, be they NHS or private, the responsible body will be the ‘hospital manager’.

- For arrangements under Continuing Health Care outside a hospital, the responsible body will be the local CCG (or Health Board in Wales).

- In all other cases – such as in care homes, supported living schemes (including for self-funders), the responsible body will be the local authority.

- For the responsible body to authorise any deprivation of liberty, it needs to be clear that:

- The person lacks the capacity to consent to the care arrangements

- The person is of unsound mind

- The arrangements are necessary and proportionate.

- To determine this, the responsible body must consult with the person and others, to understand what the person’s wishes and feelings about the arrangements are.

- An individual from the responsible body, but not someone directly involved in the care and support of the person subject to the care arrangements, must conclude if the arrangements meet the three criteria above (lack of capacity; unsound mind; necessity and proportionality).

- Where it is clear, or reasonably suspected, that the person objects to the care arrangements, then a more thorough review of the case must be carried out by an Approved Mental Capacity Professional.

- Where there is a potential deprivation of liberty in a care home, the Bill suggests the care home managers should lead on the assessments of capacity, and the judgment of necessity and proportionality, and pass their findings to the local authority as the responsible body. This aspect of the Bill has generated some negative comment, with people feeling that there is insufficient independent scrutiny of the proposed care arrangements.

- Safeguards once a deprivation is authorised include regular reviews by the responsible body and the right to an appropriate person or an IMCA to represent a person and protect their interests.

- As under DoLS, a deprivation can be for a maximum of one year initially. Under LPS, this can be renewed initially for one year, but subsequent to that for up to three years.

- Again, as under DoLS, the Court of Protection will oversee any disputes or appeals.

The new Bill also broadens the scope to treat people, and deprive them of their liberty, in a medical emergency, without gaining prior authorisation.

A critical summary of changes from Law Commission proposals

Although the Bill is based on the proposals produced last year by Law Commission following a government-commissioned review of the law on deprivation of liberty in care, the government has not included several of the commission’s key proposals in the Bill.

Those in government working on the bill had “selectively picked” from the Law Commission’s proposals in place of accepting the “whole package of measures” that had been created to produce “a robust defence” for individuals.

Among Law Commission proposals that have been omitted are the application of the LPS scheme to 16- and 17-year-olds, reforming the best interests test under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 to place a greater weight on people’s wishes and feelings and reforming section 5 of the Mental Capacity Act to restrict the availability of the defence from liability for care staff acting in relation to a person whom they reasonably believe lacks capacity to consent to the actions concerned.

Some amendments have already been tabled to the Bill by Labour shadow health minister Baroness Thornton. These would apply the reforms to people 16- and 17-year-olds and specify that the provisions must be read in a way which is compatible with Article 5 of the European Convention of Human Rights, which secures the right to liberty.

With several questions regarding the Bill and the government’s decision to stray from the Law Commission’s proposals, it is expected that there will be more challenges.

The changes include:

- The Commission’s original reference to necessity/proportionality is no longer tied specifically to risk of harm/risk to self, but simply, now, necessity and proportionality;

- The Law Commission’s proposed tort of unlawful deprivation of liberty (actionable against a private care provider) has gone;

- The LPS ‘line’ of excluding the LPS from the mental health arrangements has been changed, and the current status quo (i.e. objection) as regards the dividing line between the MCA/MHA in DOLS is maintained.

Lord O’Shaughnessy appeared to address this fact in his final comments during the second reading, saying the government would “reflect on” whether changes could be made.

“It has been clear from this debate that there is still much work to be done to provide the right kind of reforms that we all want to see,” O’Shaughnessy said.

Some amendments have already been tabled to the bill by Labour shadow health minister Baroness Thornton. These would apply the reforms to people 16- and 17-year-olds and specify that the provisions must be read in a way which is compatible with Article 5 of the European Convention of Human Rights, which secures the right to liberty.

The first day of the Lords Committee stage of the Mental Capacity (Amendment) Bill took place on 5 September. The Hansard transcript can be found here and here.

‘A backward step’

Sarah Lambert, head of policy and public affairs at the National Autistic Society (NAS), reiterated the arguments of those inside the House of Lords, saying: “NAS has substantial concerns that the bill, as drafted, does not put autistic or other individuals, who lack capacity, at the centre of decisions about their care.”

“Firstly, the bill moves away from the current position, where decisions should be made in someone’s ‘best interests’ and so risks losing sight of what is best for the individual, or what that individual wants.”

“Even though someone may lack capacity to make a decision about their living arrangements, their preferences or wishes should be a central factor in any decision about their lives. This makes it a backward step in protecting the rights people who lack capacity to consent to their care.”

“We will be working with members of the House of Lords and MPs as the bill passes through Parliament to make sure substantial amendments are made to secure the rights of autistic people and others.”

The Bill is so contentious as it does, in places, significantly depart from the recommendations of the Law Commission. Furthermore, the Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR) provided a report on the Law Commission’s proposals in July, and this report raised other issues that will need to be considered by Parliament.

One issue highlighted is the importance of establishing a clear definition of “deprivation of liberty” so that Article 5 (of the Human Rights Act) safeguards are applied to those who truly need them. The JCHR recognised that deprivation of liberty is an evolving Convention concept rooted in Article 5; the arising difficulty is how this is interpreted and applied in the context of mental incapacity.

The report says: “Parliament should provide a statutory definition of what constitutes a deprivation of liberty in the case of those who lack mental capacity in order to clarify the application of the Supreme Court’s acid test and to bring clarity for families and frontline professionals. Without such clarity there is a risk that the Law Commission’s proposals will become unworkable in the domestic sphere.”

Another problem raised is that at present, the Legal Aid Agency can refuse non-means tested certificates for challenges to DoLS where there is no existing authorisation. The current system has produced arbitrary limitations on the right of access to a court. Legal aid must be available for all eligible persons challenging their deprivation of liberty, regardless of whether an authorisation is in place, particularly given the vast number of people unlawfully deprived due to systemic delays and failures, according to the JCHR.

There is also concern raised over the term “of unsound mind”, little understood and arguably more stigmatising. The JCHR has recommended that “further thought be given to replacing ‘unsound mind’ with a medically and legally appropriate term.”

The report concludes: “DoLS apply to those with a mental disorder. LPS will apply to persons of ‘unsound mind’ to reflect the wording of Article 5. We recommend that further thought be given to replacing “unsound mind” with a medically and legally appropriate term and that a clear definition is set out in the Code of Practice.

“The interface between the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) and the Mental Health Act (MHA) causes particular difficulties. Deciding which regime should apply is complex, and causes the courts and practitioners difficulties. The Law Commission proposes to maintain the two legal regimes: the MHA would apply to arrangements for mental disorders; the LPS would apply to arrangements for physical disorders. Inevitably, problems will continue to arise at the interface between these two regimes. We are particularly concerned by two issues.

“Firstly, this proposal requires assessors to determine the primary purpose of the assessment or treatment of a mental or physical disorder–this is difficult where persons have multiple disorders. Secondly, we are concerned that there would be essentially different laws and different rights for people lacking capacity depending upon whether their disorder is mental or physical. We consider that the rights of persons lacking capacity should be the same irrespective of whether they have mental or physical disorders.”

The Law Commission’s Recommendations made an attempt to include protection for a person’s Article 8 rights (of the European Convention on Human Rights: right to a family and private life) within the proposed amendments to the Mental Capacity Act by specifying a list of applicable decisions that require a written record of decision making (including any decision regarding covert medication and contact restrictions).

The Bill makes no reference to this however (despite the government accepting this part of the proposal in their response), focusing only on Article 5 rights. This is likely to be of great concern to many campaigners and stakeholders and therefore may become a pertinent issue in Parliament. In the meantime, the current law on Article 8 authorisations and covert medication remains in place.

The current DOLS framework requires a best interest assessor to determine whether a deprivation of liberty is in a person’s best interests. The Amendment Bill, however, requires no consideration of best interests, only requiring that the arrangements are ‘necessary and proportionate.’

Although this is partly is line with the Law Commission’s proposals that the LPS should remove the focus on best interests to move away from substituted decision making (in line with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities), the Bill contains no explanation of what is meant by ‘necessary and proportionate’ or how these should be assessed. It is expected that concern will be raised in Parliament regarding the removal of best interests from the LPS and the lack of guidance surrounding necessity and proportionality.

The Bill will affect the fundamental human rights of hundreds of thousands of people with conditions such as dementia, learning disability and brain injury.

Commenting on the Bill Sue Bott CBE, Deputy CEO Disability Rights UK said:

“I am concerned with the contents of this Bill which takes the rights of disabled people backwards.

“There is nothing more serious for an individual than a decision to deprive them of their liberty yet, as it stands, this Bill will make challenging such decisions difficult and costly with little independent oversight and no commitment to taking the views of the individual into account.

“I hope members of the House of Lords will, through amendments, be able to radically improve the Bill.”

Among the concerns highlighted by Disability Rights UK are:

- The very least people, who are detained, need is information about why that decision has been made and what their rights are – there is no provision for this in the Bill

- The Bill makes access to justice worse than the current system in not providing for non-means tested legal aid

- There is no provision for the ‘cared for’ person to participate in court proceedings regarding their own liberty

- Contains offensive and out-of-date language such as ‘unsoundness of mind’

- Too much power is being given to care home managers to decide about people being deprived of their liberty

- The Bill moves UK law even further away from the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities by not providing for supported decision making and for the wishes and feeling of the person to be taken into account.

- The Bill in its current form is not supported by professionals in this area.

The right to life and state compliance with Article 2 (ECHR)

The past five years have been challenging in terms of health outcomes in the UK, they add. For example, spending on health and social care year on year has increased at a much slower rate than in previous years, while outcomes in a large number of indicators have deteriorated, including a very rapid recent increase in the numbers of deaths among mental health patients in care in England and Wales. The government has a duty and a role to provide specific care for people experiencing mental health conditions at a time of vulnerability. That role must comply with Article 2, which:

- Imposes an obligation on the State to protect the right to life.

- Prohibits the State from intentionally killing.

- Requires an effective and proper investigation into all deaths caused by the State.

- Requires the State to take appropriate steps to prevent accidental deaths by having a legal and administrative framework in place to provide effective deterrence against threats to the right to life.

The Policing and Crime Act 2017 came into effect to amend the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 and relieved coroners of the duty to hold an inquest into every death where the deceased was subject to a Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards authorisation or was deprived of their liberty through provisions in the Mental Capacity Act 2005. Coroners’ inquests into unnatural deaths involving health and social care organisations are on the increase.

Where a DOL is in force, the State has effectively curtailed the liberty of the patient; as such when the patient dies then the death is equivalent to a detention in custody. Article 14 of the Convention prohibits discrimination in the enjoyment of the Convention rights. This means that the State must ensure that the right to life of people with mental health conditions is given equal protection to that of other people.

There have been a number of other legal developments that change the way decisions about life-prolonging treatments are made, in addition to the recent court judgments and the government’s radical withdrawal of the Court of Protection’s Practice Direction 9E which addresses protections concerning serious medical treatment.

The direction was effectively abolished by the Ministry of Justice and the changes came into effect last December. The Court of Protection in English law is a superior court of record created under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. It has jurisdiction over the property, financial affairs and personal welfare of people who lack mental capacity to make decisions for themselves.

One consequence of this is the British Medical Association’s recent proposals in response to legal test cases in which judges ruled that qualified NHS staff and officials no longer required a court’s permission to withdraw artificial nutrition and hydration from those patients who are incapacitated and unable to communicate or feed themselves.

The Supreme Court justices’ decision in July supported the right of doctors to withdraw life-sustaining nutrition on their own authority, provided they had the explicit permission of the patient’s family or, where no family existed, medical proxy. If there is a disagreement and the decision is finely balanced, an application should still be made to the Court Of Protection.

Changes to protections were introduced via secondary legislation – a negative resolution statutory instrument – there was very little parliamentary scrutiny. Furthermore, as the instrument is subject to negative resolution procedure no statement regarding implications in relation to the European Convention on Human Rights was required from government ministers, nor was public consultation deemed necessary. An Impact Assessment has not been prepared for this instrument.

The fact that the UK government had already made amendments to safeguarding laws to accommodate these proposals, which took effect last December, and now plan to make it easier to remove people’s liberty under the Mental Health Act without public consultation, has caused deep unease. In the latest proposed changes to the Mental Health Act, the government seems to think it is appropriate to consider restrictions of people’s liberties as part of their overall ‘care package,’ and approach which is not compatible with human rights.

Changing legislation isn’t going to improve the lives of people with mental illness. Improving mental health services depends on funding, the right number of well-trained staff and the right resources to meet the needs of patients, their families and carers.

More information on concerns about the Bill can be found here

You can read the most recent debate about the Mental Capacity Amendment Bill in the House of Lords on 05 September 2018 here.

I don’t make any money from my work. If you want to, you can help by making a donation to help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others.

This is what happens when you close down the hospitals for (no) care in the community

LikeLiked by 1 person

NO ONE CAN JUDGE THE MANTLE THINKING’S OF RESPONSIBILITIES KEEPING BEING THE GREED AND CORRUPTION BEHIND OVER THESE MAN MADE LAW . IT IS THE NATURAL JUSTICE THAT CAN FIX THE ATTENTION OVER THE JUDGEMENT ON ANY ACTIVITIES. YOU CANNOT CONTROL GREED , CORRUPTION , IR RESPONSIBILITIES , VIOLATIONS , TILL THAT TIME @ WHEN YOU DO NOT THE EXPENSES /INVESTMENT OF POLITICIANS IN ELECTION ALONG WITH PROFIT @ ALL POLICIES /RESTRICTION AND LAW WILL BE FAILED WHEN POLITICIANS ARE NOT HONEST

LikeLike

Reblogged this on sdbast.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on michaelsnaith.

LikeLiked by 1 person

All Care home managers are suddenly experienced and expert health professionals! This is absurd!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just think how much easier and cheaper it is to manage a group of residents if you deprive them of their liberty. Now there is a perverse incentive…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have forwarded this to my MP along with a covering letter outlining my concerns and a request for a response from him detailing what actions he will be taking.

I encourage others to do the same.

LikeLiked by 3 people

great idea!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article Kitty!

Were homeless people discussed at all?

Toria…of unsound mind 😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Declaration Of Opinion.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Britain Isn't Eating!.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A long, detailed and insightful piece on the issues with the proposed amendments to the MCA and DoLs. I especially appreciate the links to supporting information and the inclusion of the responses from various organisations to the consultation. You are right to highlight the potential issues for people with LD, for those with disabilities and their carers. Very good journalism.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Jules. It was a difficult piece to write precisely because of the implications

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is a petition on this at

https://you.38degrees.org.uk/petitions/protect-the-human-rights-of-people-receiving-care-and-support

If you are interested in your future rights and freedoms do something now. I encourage everyone to sign amd promote this petition.

Don’t bury your head in the sand, this new bill will impact on you and your loved ones.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Signed and shared far and wide thank you for the link Steve

LikeLike