Absolutely.

The BBC is under pressure to examine its impartiality standard.

In this context, it was interesting to note that last night on BBC’s Question Time, it was claimed that neither the government’s nor the Labour party’s spending plans “stand up to scrutiny.” It was implied that both the Conservatives AND the Labour party were “misleading” the public. This is simply not true.

Whether the BBC failed to do some research on this issue, or whether this was a deliberate conflation of the two main parties as a result of an inbuilt bias, it points to an ongoing fundamental failure of the broadcaster to serve the public interest and deliver balanced and impartial commentary.

Yesterday in the Institute of Fiscal Study’s (IFS) analysis of the three major parties’ manifestos, it was conceded that Labour’s “vision is of a state not so dissimilar to those seen in many other successful western European economies”. Furthermore, under a Labour government, public spending would be at a lower share of national income than Germany and many other European countries.

The BBC’s headline reporting, claiming that both Labour’s and the Conservative’s spending plans were “not credible”, does not acknowledge the IFS’s broader and more important message, following the initial analysis: that the UK faces a fundamental choice about its future direction.

IFS director, Paul Johnson, noted that the Conservatives were offering “more of the same”(austerity) and that “there is little to say about Conservative proposals” since “they believe most aspects of public policy are just fine as they are”.

In contrast, Johnson argued that Labour has “vast ambition” and that it wants to “change everything” – but he did question whether this was achievable in the short term. That’s his job.

It’s worth noting, however, that Labour’s economic modeling is a big shift away from neoliberalism. With a strong element of ‘mixed economy thinking’, Labour’s manifesto embraces Keynesianism, the model upon which are post-war democratic settlement was based – which gave rise to the creation of the NHS, the welfare state, legal aid, social housing among many other social gains. As such, it is difficult to judge this within a dominant neoliberal framework, since the fundamental ideological premises of the two models are poles apart.

For some context, it’s well worth reading George Monbiot’s excellent article: Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems.

Economist John Maynard Keynes was writing at the time of the Great Depression during the 1930s, he sought to understand what went wrong. Keynes disagreed with the classical liberal model – laissez faire – in which governments did not intervene in the economy in the event of recession. Instead he advocated for increased government expenditures and lower taxes to stimulate demand and pull the global economy out of the depression. This approach also led to policies which emphasised the welfare of ordinary citizens as a priority.

While Keynesian theory allows for increased government spending during recessionary times, it also calls for government restraint in a rapidly growing economy. This prevents the increase in demand that spurs inflation. It also forces the government to cut deficits and save for the next ‘down cycle’ in the economy.

The BBC’s coverage of the initial IFS report

The BBC presented cherry-picked comments from the IFS’ initial verdict of party manifestos, and excluded any analysis from economists and academics.

To clarify, the IFS specifically criticised the Labour party’s planned increases to public investment, arguing that the public sector currently lacks the capacity to “ramp up that much, that fast”. As it stands.

That does not suggest the Labour party have been dishonest at all.

But more importantly, the IFS appears to have accepted the central argument that Labour makes: that increasing spending and investment has a multiplier effect that would boost economic growth. This is a sharp shift away from the neoliberal framework that was put in place by Margaret Thatcher, which had a central strategy of austerity and low public spending.

The IFS concluded that Labour’s plans, surprisingly, could boost output by £22bn, returning about half that in tax – vastly more than the £5bn assumed by Labour’s own plans. The institute say Labour’s manifesto should be seen as “a long-term prospectus for change rather than a realistic deliverable plan for a five-year parliament”. This statement somewhat mitigates the early concern regarding the achievability of Labour’s plans in the short term.

The public and governments commonly overestimate what can be done in two years, but underestimate what can be achieved in 10. Under a Labour government, Britain would be a radically different country at the end of the 2020s than at the beginning. Under the Conservatives, nothing at all would change. Austerity would stifle growth and entrench inequality further.

In fact the Director of the IFS said that, under Tory plans, spending on public services apart from healthcare would still be 14% lower by 2023/24 than it was in 2010/11.

Despite this, he said the Conservatives were continuing to “pretend that tax rises will never be needed to secure decent public services” – and said a pledge from the party not to raise income tax, national insurance or VAT over the next five years was “ill-advised”.

“It is highly likely that the Conservatives would end up spending more than their manifesto implies, and thus taxing or borrowing more,” Johnson added.

Many economists believe that fundamental change and investment is now needed to enable the economy to gain the required momentum to escape the stagnation in which it has been trapped for a decade. As the IFS said yesterday, the choice could not be starker. The Conservatives are only offering the UK more of the same.

163 economists and academics wrote to the Financial Times, in support of the Labour Party’s manifesto. The economists signed a public letter offering broad support for its proposals for higher public investment to kick start growth and raise productivity. The letter lamented Britain’s poor economic performance of the past decade, and called for “a serious injection of public investment” and said Britain would benefit from greater state involvement in national economic management.

“It seems clear to us that the Labour party has not only understood the deep problems we face, but has devised serious proposals for dealing with them. We believe it deserves to form the next government,” the letter said.

This support from economists for Labour’s proposals comes as a boost for the party at a time when the Conservatives, who have led the government since 2010, are attacking the party’s manifesto as “likely to cause an economic crisis within months.”

However, the Conservatives inherited an economy that had been taken out of recession caused by the global crash, by the last quarter of 2009. The Conservatives caused another UK recession in 2011. Furthermore, it was the Conservative government that presided over the loss of the UK’s Fitch and Moody’s triple A international credit status. It’s remarkable that the government managed to maintain the deceit of “economic competence” as long as they have, in the face of such blatant mismanagement of UK finances.

Michael Jacobs, professor of political economy at Sheffield university, who co-ordinated the letter, said it had been “surprisingly easy” to find economists willing to sign. Many know that fundamental change and a shift away from the neoliberal model is essential for the future prosperity of the UK.

“The easiest thing for academic economists to do is sit on the fence,” he said, adding that “although academics generally do not go out on a limb, most had been willing to say that the UK faced a big choice and that enough of Labour’s programme accords with their own views”. This is a positive endorsement for Labour’s manifesto.

David Blanchflower was one of the signatories, he is tenured economics professor at Dartmouth College, inthe US. Others include Victoria Chick, emeritus professor of economics at University College London; Meghnad Desai, emeritus professor of economics at the London School of Economics; Stephany Griffith-Jones, emeritus professorial fellow at the Institute of Development Studies; and Simon Wren-Lewis, emeritus professor of economics at Merton College, University of Oxford.

The letter challenged the Conservative claim that it had run a “strong economy” since 2010, saying there had been:

“10 years of near zero productivity growth”, stagnant corporate investment, low wage growth and increasingly strained public services. With business investment having fallen for most of the past two years, the authors said higher public investment would help raise growth and productivity on its own as well as “leverag[ing] private finance attracted by the expectation of higher demand”.

The IFS accepted Labour’s method of boosting the economy via investment. After a lost decade under the Tories, it’s what Britain needs.

The contrasts within the IFS analysis are highlighted by Tom Kibasi, a writer and researcher on politics and economics. Writing in the Guardian, he says:

“The Tories appear to have broken with the political consensus formed after the Brexit referendum: that the public are hungry for change. Their commitment to the status quo is both an enormous political gamble and a rebuke to working people whose wages have been stagnant for a decade, to the sick waiting for NHS treatment, the elderly suffering from a social care crisis, and more than 4 million children living in poverty.

“It is hard to view it as anything but a monument to born-to-rule entitlement: victory is assumed rather than earned. In the face of a social and economic crisis, the Tories will face the electorate with a solemn promise to do nothing.

“Yet the emptiness of the Conservative manifesto should come as no surprise: it is the logical conclusion of a lost decade for Britain. For nearly 10 years now, Conservative thinking has been defined by the presence of absence: an ideological programme of austerity to slash back the state. The IFS confirmed today that austerity was now “baked in” to Tory plans for the future. Where an active state should be, the Tories intend to leave a void.

“As a political project, Brexit merely prolongs the void, with a false promise that all the problems of the present will magically be solved. In truth, there is no substantive problem to which Brexit is the solution; instead, it nourishes and sustains the nothingness. The IFS starkly warned that Johnson’s “die in a ditch” promise to terminate the transition period by the end of 2020 risked doing serious economic damage.

“The impulse to destroy rather than to create has become the hallmark of 40 years of Tory government – wrecking our industrial base and trade unions under Margaret Thatcher, the public realm under David Cameron, and our international relationships under Theresa May and Boris Johnson.

“But perhaps the most revealing aspect of the IFS analysis was the dishonesty of the Conservatives’ stated plans. The IFS points out that the Tories “would end up spending more than their manifesto implies and thus taxing or borrowing more”, with their proposals riddled with uncosted commitments and vague aspirations.

“Perhaps it should be little surprise that the character of the Tory manifesto reflects the man who leads their party.”

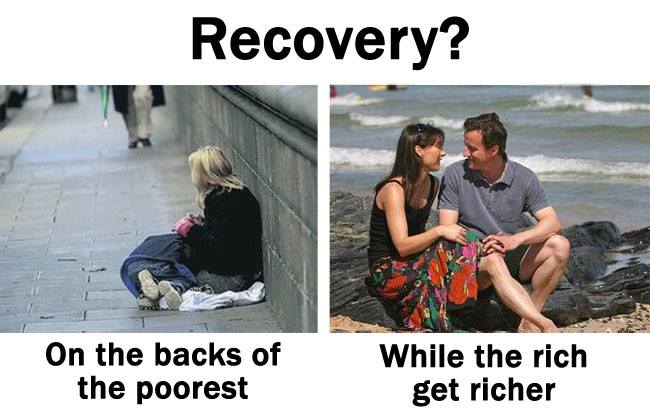

After a decade of austerity, many people are conditioned to accept it was somehow ‘necessary’ rather than it being an ideologically driven choice – one of several political choices. After a decade of austerity, many are incredulous at the idea that the sixth-largest economy in the world could afford to provide a decent standard of living for its people – that things could be better for them.

But they can be so much better.

The power of the austerity argument is, of course, reinforced by the experience of poverty.

Paul Johnson wrote: “The bigger picture with regard to Labour’s plans is that it is planning a much bigger role for the state in the running of the economy. That’s what nationalisations mean and it’s what government spending an extra 2 per cent of national income on capital projects means. The real resources — workers, raw materials, machinery — would be diverted from the private sector to the public.

“The question, then, is not so much how much all this would all cost; rather, it is how confident are we that these resources would be put to better use in public hands than in private.”

The answer is this: public money in public hands profits the public and is ploughed back into the economy. By contrast, low public spending and investment and privatisation squeeze the public and costs us in a myriad of ways. Private profit takes money out of the economy, leaving a black hole. It drives wages and living standards down. It drives the quality of public services and utilities down, since the profit motive places profit about meeting public needs.

Labour’s manifesto promises a much needed break from the neoliberal model, which has entrenched inequality and fuelled a growth in absolute poverty within our society. As an ideology, neoliberalism in practice has demonstrated a fundamental incompatibility with human rights and democracy, particularly evident over the last few years, with reports from the United Nations condemning government policies and the devastating impacts these have had on ordinary people, and in particular, on the violation of disabled people’s human rights, and those of the poorest citizens.

It’s worth reading Labour’s economic programme isn’t just radical – it’s credible, too, written by Grace Blakeley, who is the New Statesman’s economics commentator and a research fellow at IPPR.

You can also hear the comments that Fiona Bruce made on Question Time, on political trust and the IFS report, among other things here.

I don’t make any money from my work. But you can help if you like by making a donation to help me continue to research and write free, informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.