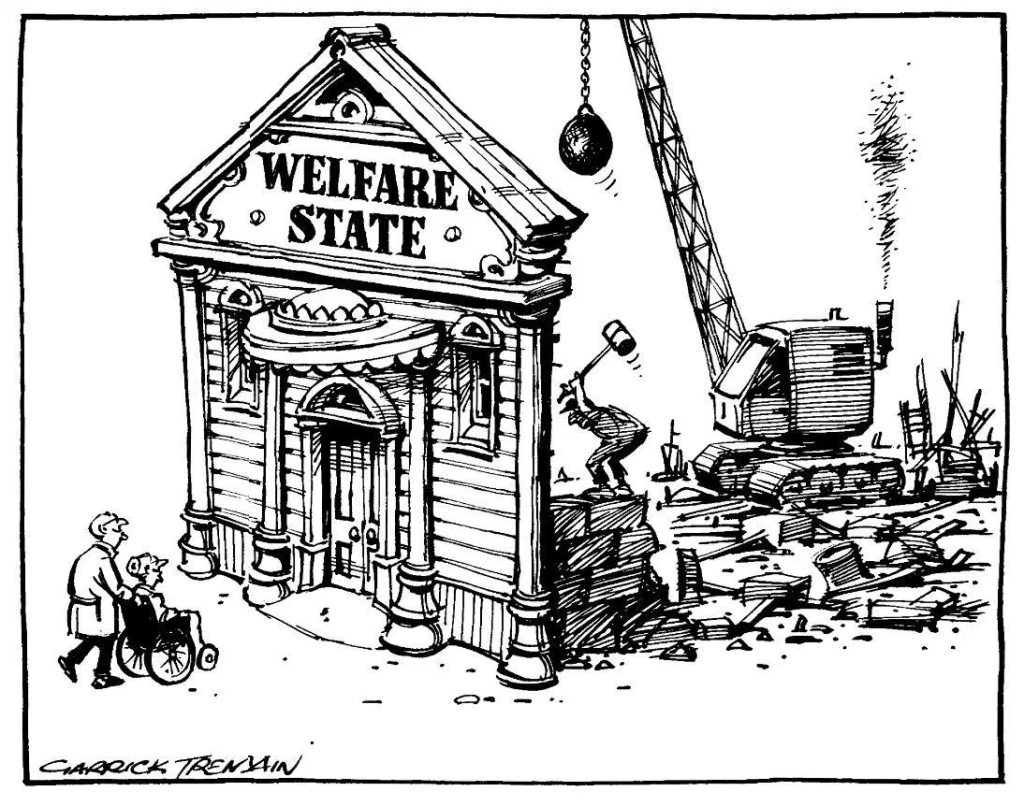

The government has a problem with the public actually using public services

The government announced the creation of the Joint Health and Work Unit and the Health and Work Service in 2015/16, both with a clear remit to cut benefits and “get people into work.” Given that mental health is a main cause for long-term sickness absence in the UK, a key aspect of this policy is to provide mental health services that get people back into work.

There has already been an attempt to provide mental health services for people who claim social security support, which includes a heavily resisted pilot to put therapists into job centres. Another heavily opposed government proposal was announced as part of the health and work pilot programme to put job coaches in GP surgeries. The proposals have been widely held to be profoundly anti-therapeutic, potentially very damaging and professionally unethical.

With such a narrow objective, the delivery will invariably be driven by an ideological agenda, politically motivated outcomes and meeting limited targets, rather than being focused on the wellbeing of individuals who need support and who may be vulnerable. I also discovered almost by chance back in 2015 that the Nudge Unit team have been working with the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department of Health to trial social experiments aimed at finding ways of: “preventing people from falling out of the jobs market and going onto Employment and Support Allowance (ESA).”

“These include GPs prescribing a work coach, and a health and work passport to collate employment and health information. These emerged from research with people on ESA, and are now being tested with local teams of Jobcentres, GPs and employers.” Source: Matthew Hancock’s conference speech: The Future of Public Services.

GPs have raised their own concerns about sharing patient data with the Department for Work and Pensions – and quite properly so. Pulse reported that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) planned to extract information from GP records, including the number of Med3s or so-called “fit notes” issued by each practice and the number of patients recorded as “unfit” or “maybe fit” for work, in an intrusive move described by GP leaders as amounting to “state snooping.”

Part of the reason for this renewed government attack on sick and disabled people is that the government’s flagship fit note scheme, which replaced sick notes five years ago in the hope it would see GPs sending thousands more employees back to workto reduce sickness-related absence, despite GPs having expressed doubts since before its launch, has predicably failed.

The key reason for the failure is that employers did not take responsibility for working with employees and GPs seriously, and more than half (59%) of employers said they felt unable to support employees by making all of the legally required workplace adjustments for those who had fit notes signed as “may be fit for work.” Rather than address this issue with employers, the government has decided instead to simply coerce patients back into work without essential support.

Another reason for the failure of this scheme is that most people who need time off from work are ill and genuinely cannot return to work until they have recovered. Regardless of the government’s concern for the business and state costs of sick leave, people cannot be simply ushered out of illness and into work by the state to “contribute to the economy.” When a GP says a person is “unfit for work”, they generally ARE unfit for work, regardless of whether the government likes that or not.

The government have planned to merge health and employment services, and are now attempting to redefine work as a clinical outcome. Unemployment has been stigmatised and politically redefined as a psychological disorder, the government claims somewhat incoherently that the “cure” for unemployment due to illness and disability, and sickness absence from work, is work.

The latest strand of this ideological anti-welfare crusade was recently announced: the NHS is to hire 300 employment coaches who will find patients jobs to “keep them out of hospital.” The Individual Placement and Support services (IPS) is aimed at ‘supporting’ people with severe mental illness to seek work and ‘hold down a job’. Job coaches will offer assistance on CVs, interview techniques and are expected to work with 20,000 people by 2021. Pilot schemes running in Sussex, Bradford, Northampton and some London boroughs suggest that the coaches manage to find work for at least a quarter of users. The scheme is to be extended nationwide.

The roll out of mental health employment specialists across the country is based on analysis of the pilots, which is claimed to show that 2,300 patients have been helped into work in the last year. However, the longer term consequences of the programme are not known, and it is uncertain if there will be any meaningful monitoring regarding efficacy, safeguarding and the uncovering of unintended consequences and risks to participants.

It is held that those in work tend to be in better health, visit their GP less and are less likely to need hospital treatment. The government has assumed that there is a causal relationship expressed in this common sense finding, and make an inferential leap with the claim that “work is a health outcome”.

However, support for this premise is not universal. Some concerns which have been reasonably raised are commonly about the extent to which people will be ‘pushed’ into work they are not able or ready to do, or into bad quality work that is harmful to them, under the misguided notion that any work will be good for them in the long run.

Of course it may equally be the case that people in better health work because they can, and have less need for healthcare services simply because they are relatively well, rather than because they work.

Undoubtedly there are some people who may be able to work and who want to, but struggle to find suitable employment without adequate support. This section of the population may also face the lack of knowledge, attitudes and prejudices of potential employers regarding their conditions as a further barrier to gaining appropriate employment. The scheme will be ideal for supporting this group. That is, however, only provided that engagement with the service is voluntary, and does not become mandatory.

It must also be acknowledged that there are some people who are simply too ill to work. Again, it’s a serious concern that this group may be pressured and coerced to find employment, which may prove to be detrimental to their wellbeing. Furthermore, placing them in work may present unacceptable risk to both themselves and others. How can we possibly know in advance about the longer term risks presented by the impact of an illness, and the potential effects of some medications in the workplace? If something goes catastrophically wrong as a consequence of someone taking up work when they are too unwell to work, who will hold the responsibility for the consequences?

In the current political context where the public are told “work is the route out of poverty” and “work is a health outcome”, people feel obliged to try to work, when they believe they can. But what happens when they are wrong in that belief? Who is responsible, for example, when someone has a loss of consciousness or an episode of altered awareness, caused by a condition or medication, while operating machinery, at the wheel of a taxi, bus or refuse waggon?

Harry Clarke, who believed that he was fit for work, suffered a loss of consciousness on 22 December 2014 while at the wheel of a moving refuse lorry in Glasgow city centre, resulting in six deaths and leaving 15 people injured. Following numerous warnings from the court about his right to remain silent, Clarke refused to answer key questions about numerous doctors visits and medical tests for dizziness, fainting, vertigo, heart problems, tension headaches, operations on hands and knee pain dating back to 1976. However, one of the biggest revelations of the inquiry was Clarke’s lengthy medical history, which showed he had suffered episodes of dizziness and fainting for decades prior to the tragic crash.

Yet during an inquiry about the case, a health care professional who assessed the Glasgow bin lorry crash driver for the renewal of his HGV licence in 2011 would have deemed him only “temporarily unfit to drive” if she had known he had fainted the year before the accident. Furthermore, Clarke’s conditions would probably not have made him eligible for Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). Dr Joanne Willox told the inquiry panel at Glasgow Sheriff Court that she saw Mr Clarke on 6 December 2011 at the request of his employer Glasgow City Council to complete a HGV renewal application form with him which was to be submitted to the DVLA.

Dr Willox, an occupational medical adviser for the private company Bupa, on behalf of Glasgow City Council, did not have access to his medical records. She could have requested the records with the patient’s consent if she considered it necessary, though this was not the normal practice and it may have taken time to get the records.

She said it would have been “helpful” to have the records. The inquiry revealed that Clarke had a history of fainting and dizziness, and had in fact previously suffered a similar episode while at the wheel of a stationary bus, in 2010.

The horrific case highlights several issues, not least that employment of people with unpredictable or undiagnosed medical conditions does not only pose a threat to the person, but it may potentially be contrary to public safety, too. It also highlights that a privately contracted occupational health professional who had no knowledge of Clarke’s medical history, was unsuitably tasked to make a judgement about his potential ability to work as a refuse waggon driver. Employing people who are ill and later found to be unfit for the role is potentially in contravention of the Health and Safety at Work Act.

Another horrific example of the dangers presented by placing trust in unqualified bureaucrats and the state – who have ideological interests that often lie in conflict with those of patients – to make decisions about citizens’ health and welfare arose when a manager at Birkenhead Benefit Centre in Liverpool wrote a letter, addressed to a GP, regarding a seriously ill patient. It said:

“We have decided your patient is capable of work from and including January 10, 2016.

“This means you do not have to give your patient more medical certificates for employment and support allowance purposes unless they appeal against this decision.

“You may need to again if their condition worsens significantly, or they have a new medical condition.” (My emphasis)

The job centre manager was wrong. The health care professional, assessing the patient on behalf of the private company contracted to carry out the ESA assessment, on behalf of the government, was wrong.

The patient, James Harrison, had been declared “fit for work” and the letter stated that he should not get further medical certificates. However, 10 months after the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) contacted his doctor without telling him, James died, aged 55.

He was clearly not fit for work.

James’ grieving daughter, Abbie, said: “It’s a disgrace that managers at the Jobcentre, who know nothing about medicine, should interfere in any way in the relationship between a doctor and a patient.

“They have no place at all telling a doctor what they should or shouldn’t give a patient. It has nothing to do with them.

“When the Jobcentre starts to get involved in telling doctors about the health of their patients, that’s a really slippery slope.” (See Jobcentre tells GP to stop issuing sick notes to patient assessed as ‘fit for work’ and he died.)

It has become very evident over recent years that the labour market is not delivering an adequate income for many citizens and despite “record levels of employment”, the problem seems to be getting bigger. The government’s answer to the problem has been to extend punishment those on low pay, rather than tackle employers who pay exploitative, low wages.

The neoliberal narrative and Conservative antiwelfarism

Some of the underpinning language used to justify this approach also troubles me, as it is clearly couched in economic terms. It’s about cutting costs, propping up the economy as a whole and “rewarding” tax payers. Here, it is implied that people who are ill are somehow a burden on tax payers. However, most people who become ill have also worked and contributed to the Treasury. Furthermore, people who aren’t in employment also pay taxes, too, be it VAT, council tax, or a range of other stealth taxes from which even the poorest citizens are no longer exempted.

Claire Murdoch, NHS England national mental health director, said: “Helping people with mental ill health to find and keep a job is good for individual wellbeing and good for the health of our economy. Tackling severe mental illness is not just about getting medication and treatment right, but ensuring people can recover to live independently with their condition, including the reward and satisfaction of getting and keeping a job.

“In our 70th year, mental health is one of the NHS’ top priorities, and ensuring services are integrated, so people get whole-person care, means our patients get better outcomes and taxpayers are rewarded as treatment is more efficient. One in seven of us will go through mental ill health whilst at work, so delivering a safety net, to help people back in to work when they fall ill, will minimise harm and make our country’s workforce more productive.”

NHS England say: “As part of patients’ care and support package, work coaches in NHS Individual Placement and Support (IPS) services, offer advice about finding a job, help them to prepare for an interview and can speak with potential employers about how someone’s condition can be managed so that they can work effectively while staying in good health.

“The trained specialists also improve the health of people with severe mental illness, reducing the need for urgent hospital admissions and GP appointments. Research shows that type of support can free up as much as £6,000 per patient, which can be invested in other frontline care.”

Again, the language is loaded, it’s a narrative with a scattering of casual cost-cutting phrases and prioritises a ‘productive workforce.’ There isn’t any discussion regarding the claim to ‘minimise harm’, it seems to be assumed that work in itself will take care of that. It’s also a little worrying that employers and work coaches are to be included in the ‘management’ of employees’ illnesses. When I am ill, I don’t want the advice or ‘management’ of a boss or a work coach, I want impartial medical diagnosis, treatment and advice from my doctor, not a ‘nudge’ or trite armchair psychology and pseudoscientific platitudes from the state.

It’s difficult to see how someone with a serious, chronic or progressive illness, can actually ‘manage’ their illness and ‘move back into work.’ The use of the extremely misinformed, patronising and very misleading term manage implies that very ill people actually have some kind of choice in the matter.

Implicit in this narrative is the idea that illness is caused by deviant behaviours. The ‘cure’ therefore, is to simply address and remedy the faulty behaviours.

The sick role and the resurrection of Talcott Parsons: disciplining disabled people

There is a lack of coherence within the narratives of contemporary Conservative governance, which is simultaneously neoliberal – grounded in free market principles and the ideal of a small, ‘non-intrusive’ state – and paternalism – which is founded on an authoritarian, large, extremely intrusive state, which is designed to tell people what is best for them and nudging citizens’ behaviours towards government defined policy outcomes.

The tension between neoliberalism and paternalism which outlines current policy approaches to disability and employment policy is filled with ambiguity, inconsistency and contradiction in its definition and understanding of the subject, the nature of the ‘problem’ and the policy ‘solutions’. On the one hand, neoliberalism is a doctrine that demands the withdrawal of social support mechanisms such as welfare, health care and public services, on the other, paternalism is based on state interventions designed to extend politically defined ‘optimal outcomes’.

These apparently contradictory narratives have been embodied in discipline of behavioural economics, which is largely aimed at enforcing the alignment of public expectations, attitudes and behaviours with neoliberal outcomes. It’s a prop for dogma and the status quo. Behavioural economics is concerned with reducing citizens’ expectations of social provision, while enforcing self reliance, and with providing justification narratives for neoliberal policies.

I have written critical accounts of this somewhat draconian Conservative neoliberal paternalism on more than one occasion. The Conservatives place emphasis on highlighting the obligations of citizens, rather than on their rights, and this is why the work of Talcott Parsons in the early 1950s is especially appealing to them.

Behavioural medicine was partly influenced by Talcott Parsons’ The Social System, 1951, and his work regarding the sick role, in which he analysed in a framework of citizen’s roles, social obligations, reciprocities and behaviours within a wider capitalist society, with an analysis of rights and obligations during sick leave. From this perspective, the sick role is considered to be sanctioned deviance, which disturbs the function of society. (It’s worth comparing that the government are currently focused on economic function and enhancing the supply side of the labour market.)

Behavioural medicine more generally arose from a view of illness and sick role behaviours as characteristics of individuals, and these concepts were imported from sociological and sociopsychological theories.

However, it should be noted that there is a distinction between the academic social science disciplines, which include critical perspectives of conflict and power, for example, and the recent technocratic “behavioural insights” approach to public policy, which is a monologue that doesn’t include critical analysis, and serves as prop for neoliberalism, conflating citizen’s needs and interests with narrow, politically defined economic outcomes.

We have a government that has regularly misused concepts from psychology and sociology, distorting them to fit a distinct framework of ideology, and justification narratives for draconian policies, usually entailing the diversion of public funds from public services and the provision of social security to wards rewards for the wealthiest citizens, usually in the form of tax cuts. Parsons’ work has generally been defined as sociological functionalism, and functionalism tends to embody very conservative ideas.

From this perspective, sick people are not productive members of society; therefore this deviation from the norm must be policed. This, according to Parsons, is the role of the medical profession. More recently, however, we have witnessed the rapid extension of this role to include extensive State policing of sick and disabled people, and the introduction of increasingly coercive measures to push citizens into self managing their health conditions, while the medical profession have been increasingly politically sidelined in their provision of advice, care and support, regarding sickness and employment.

Last year, the government proposed extending ‘fit note’ certification beyond GPs to a wider group of non-specialist healthcare professionals, including physiotherapists, psychiatrists and senior nurses, to better ‘identify health conditions and treatments’ to help workers go back into their jobs faster. This is very worrying, since it entails the diagnosis and treatment of conditions by people who are not qualified to undertake this role.

‘Fit notes’ are specifically designed to ‘help’ patients develop a return to work plan, and are meant to be tailored to their individual needs. However, the introduction of fit notes – a somewhat Orwellian title that refuses to acknowledge people get ill, or permit citizens time to recover, which replaced sick notes – failed to produce an increase in a more rapid return to work for patients generally, mainly due to the fact that employers failed to support patients with adequate workplace adjustments to accommodate their return.

It seems many of the psychosocial advocates have ignored the rise of chronic illnesses and the increasing pathologisation of everyday behaviours in health promotion. Parson’s sick role came to be seen as a negative referent rather than as a useful interpretative tool. Parsons’ starting point is his understanding of illness as deviance. Illness is the breakdown of the general “capacity for the effective performance of valued tasks” (Parsons, 1964: 262). Losing this capacity disrupts “loyalty” to particular commitments in specific contexts such as the workplace.

Theories of the social construction of disability also provide an example of the cultural meaning of certain health conditions. The roots of this anti-essentialist approach are found in Stigma by Erving Goffman (1963), in which he highlights the social meaning physical impairment comes to acquire via social interactions. The social model of disability tends to conceptually distinguish impairment (the attribute) from disability (the social experience and meaning of impairment). Disability cannot be reduced to a mere biological problem located in an individual’s body (Barnes, Mercer, and Shakespeare, 1999). Rather than a “personal tragedy” that should be fixed to conform to medically determined standards of “normality” (Zola, 1982), disability becomes politicised.

The issues we then need to confront are about the obstacles that may limit the opportunities for individuals with impairments, and about how those social barriers may be removed.

From a social constructionist perspective, emphasis is placed on how certain illnesses come to have cultural meanings that are not reducible to or determined by biology, and these cultural meanings further burden the afflicted (as opposed to burdening “the tax payer” , the health services, those with profit seeking motives, or the state.)

So to clarify, it is wider society and governments that need a shift in disabling attitudes, perceptions and behaviours, not disabled people.

The insights that arose from the social construction of disability approach are embodied in policies, which include the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, which included an employers’ duty to ensure reasonable adjustments/adaptations; the more recent Equality Act 2010 and the Human Rights Act 1998, which provides an important tool for disabled people to use to challenge discrimination, violations to their human rights and unacceptable treatment.

In contrast, Parsons invokes a social contract in which society’s “gift of life” is repaid by continued contributions and conformity to (apparently unchanging, non-progressive) social expectations. For Parsons, this is more than just a matter of symbolic interaction, it has far more concrete, material implications: “honour” (deserving) and “shame” (undeserving) which accompany conformity and deviance, have consequences for the allocation of resources, for notions of citizenship, civil rights and social status.

Parsons never managed to accommodate and reflect social change, suffering and distress, poverty, deprivation and conflict in his functionalist perspective. His view of citizens as oversocialised and subjugated in normative conformity was an essentially Conservative one. In fact, the instituted Nudge Unit at the heart of the Cabinet Office and a proliferation of nudge-laden behaviourist policies over recent years indicates this view is a Conservative ideal.

Furthermore, Parsons’ systems theory was heavily positivistic, anti-voluntaristic and profoundly dehumanising. His mechanistic and unilinear evolutionary theory reads like an instruction manual for the capitalist state.

Parsons thought that social practices should be seen in terms of their function in maintaining order and social structure. You can see why his core ideas would appeal to Conservative neoliberals and rogue multinational companies (such as Unum, who had a hand in the government’s Work, Health and Employment green paper). Conservatives have always been very attached to tautological explanations (insofar that they tend to present circular arguments.)

One question raised in this functional approach is how do we determine what is functional and what is not, and for whom each of these activities and institutions are functional. If there is no method to sort functional from non-functional aspects of society, the functional model is tautological – without any explanatory power to why any activity is regarded as “functional.” The causes are simply explained in terms of perceived effects, and conversely, the effects are explained in terms of perceived causes).

Because of the highly gendered division of labour in the 1950s, the body in Parsons’ sick role is a male one, defined as controlled by a rational, purposive mind and oriented by it towards an income-generating performance. For Parsons, most illness could be considered to be psychosomatic.

The ‘mind over matter’ dogma is not benign; there are billions of pounds and dollars at stake for the global insurance industry, which is set to profit massively to the detriment of sick and disabled people. The eulogised psychosocial approach is evident throughout the highly publicised UK PACE Trial on treatment regimes that entail Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and graded exercise. By curious coincidence, that trial was also significantly about de-medicalising illnesses. Another curious coincidence is that Mansel Aylward sat on the PACE Trial steering group.

Work will set you free

Arbeit macht frei (‘work makes you free’) is a German expression which comes from the title of a novel by German philologist Lorenz Diefenbach, Arbeit macht frei: Erzählung von Lorenz Diefenbach (1873), in which gamblers and fraudsters find the path to virtue through work. The Weimar Republic in the 1920s, and later, the Nazis, found the leading character of Diefenbach’s book, whose achievements are defined by ‘concentrating on doing his work’, compelling.

The phrase was used to promote German employment policies. The slogan was placed at the entrances to a number of Nazi concentration camps. It strikes as an almost mystical declaration that self-sacrifice in the form of endless labour does in itself bring a kind of spiritual freedom. However, given the true role of concentration camps such as Auschwitz during the Holocaust as well as the individual prisoner’s knowledge that once they entered the camp, freedom was not likely to be gained by any means other than their death, the terrible and cruel irony of the slogan becomes clear. And the lie.

Though the context and wording has changed – “work is a health outcome” – and full employment at any cost is the neoliberal goal, the idea that work has some mystical benefit, such as curing illness, or even simply alleviating poverty and inequality, remains a lie.

The British Psychological Society (BPS) has expressed concerns about the idea that employment (of whatever type) should be recognised as a “health outcome”. The Society recognise that suitable work can be good for wellbeing – but this very much depends on the type and quality of work and its social context.

Furthermore, my own view is that the IPS programme will make it more difficult to ensure and maintain the political independence of health professionals. The private and confidential patient-doctor relationship ought to be a safe space, where citizens may address medical health problems, and doctors can provide support for people who are ill. The government is creating yet another space for an intrusive, overextension of the coercive arm of the state to “help people into work”, regardless of whether or not they are actually well enough to cope with working.

Placing employment advisors in the NHS will not address inequality, and the social conditions that are the consequence of political decision-making and imposed economic frameworks, so it permits the government and society to look the other way, while the government continue to present mental illness as an individual weakness or vulnerability, and a consequence of “worklessness” rather than a fairly predictable result of living in a highly unequal, competitive society, and arising because of experiences of living stigmatised, marginalised lives because of politically expedient policy-directed material deprivation.

Feeding a myth

I found a document almost by accident, while researching the Health, Work and Disability green paper a couple of years back. It presents further evidence that government policy is not founded on empirical evidence, but rather, it is often founded on deceitful contrivance. The Department for Work and Pensions research document published back in 2011 –Routes onto Employment and Support Allowance– said that if people believed that work was good for them, they were less likely to claim or stay on disability benefits.

It was decided that people should be “encouraged” to believe that work was “good” for health. There is no empirical basis for the belief, and the purpose of encouraging it is simply to cut the numbers of disabled people claiming ESA by “encouraging” them into work. Some people’s work is undoubtedly a source of wellbeing and provides a sense of purpose.

That is not the same thing as being work being miraculously “good for health”. For a government to use data regarding opinion rather than empirical evidence to claim that work is “good” for health indicates a ruthless mercenary approach to fulfill their broader aim of dismantling social security and relentless determination to uphold their ideological commitment to supply-side policy, regardless of the harmful social costs.

From the document: “The belief that work improves health also positively influenced work entry rates; as such, encouraging people in this belief may also play a role in promoting return to work.”

The aim of the research was to “examine the characteristics of ESA claimants and to explore their employment trajectories over a period of approximately 18 months in order to provide information about the flow of claimants onto and off ESA.”

The document also says: “Work entry rates were highest among claimants whose claim was closed or withdrawn suggesting that recovery from short-term health conditions is a key trigger to moving into employment among this group.”

“The highest employment entry rates were among people flowing onto ESA from non-manual occupations. In comparison, only nine per cent of people from non-work backgrounds who were allowed ESA had returned to work by the time of the follow-up survey. People least likely to have moved into employment were from non-work backgrounds with a fragmented longer-term work history. Avoiding long-term unemployment and inactivity, especially among younger age groups, should, therefore, be a policy priority. ”

“Given the importance of health status in influencing a return to work, measures to facilitate access to treatment, and prevent deterioration in health and the development of secondary conditions are likely to improve return to work rates”

Rather than make a link between manual work, lack of reasonable adjustments in the work place and the impact this may have on longer term ill health, the government chose instead to promote the cost-cutting and unverified, irrational belief that work is a “health” outcome. Furthermore, the research does conclude that health status itself is the greatest determinant in whether or not people return to work. That means that those not in work are not recovered and have longer term health problems that tend not to get better.

Work does not “cure” ill health. To mislead people in such a way is not only atrocious political expediency, it’s actually downright dangerous.

As neoliberals, the Conservatives see the state as a means to reshape social institutions and social relationships based on the model of a competitive market place. This requires a highly invasive power and mechanisms of persuasion, manifested in an authoritarian turn. Public interests are conflated with narrow economic outcomes. Public behaviours are politically micromanaged. Social groups that don’t conform to ideologically defined economic outcomes are politically stigmatised and economically outgrouped.

Nicola Oliver, from Northamptonshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, said: “Employment support linked to mental health means people can live the life they want to lead.

“If you help someone into a job they really like – which means they are inspired to get up in the morning and want to manage their symptoms – they’re likely to say to their clinician ‘This is what I want to do, help me to overcome these barriers.’ In this way, you’re motivating the person to manage their own condition” (My emphasis).

Mental health employment specialists in the IPS service are part of community mental health teams. They currently operate in parts of the country including Sussex, Bradford, Northampton and some London boroughs, which have seen 9,000 people in the past twelve months. NHS England will be providing £10 million funding to expand access over the next two years, with further investment to follow. By 2021, NHS England anticipates that 20,000 people with severe mental illness will receive tailored care and employment advice via the NHS, suggesting that around 5,000 people with mental ill health avoid unemployment thanks to ‘better health care’.

IPS is one of a number of integrated mental health services which are being introduced or expanded across England, as part of NHS England’s Five Year Forward View for Mental Health, described as a “transformation and investment programme to improve care between 2016 and 2021.”

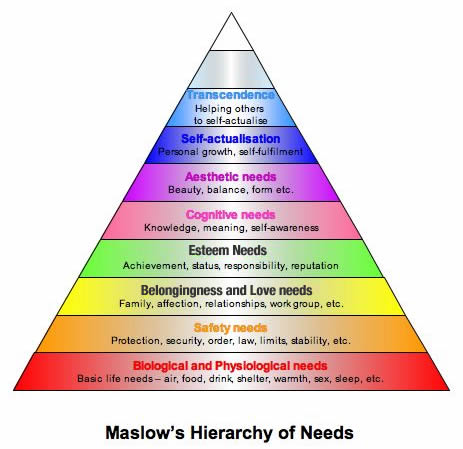

People can only work when their basic needs are met

Despite the government’s rhetoric on welfare “dependency”, and the alleged need for removing so-called “perverse incentives” from the social security system by imposing a harsh conditionality framework and a compliance regime – using punitive sanctions – and work capability assessments designed to preclude eligibility to disability benefits, research shows that generous social security regimes make people more likely to want to work, not less. I have written at length over the last few years about why a punitive welfare system can never work, as the government claim, to “incentivise people to find employment. See, for example, The Minnesota Starvation Experiment provided empirical evidence that demonstrates clearly why welfare sanctions can’t possibly work as an “incentive” to “make work pay”).

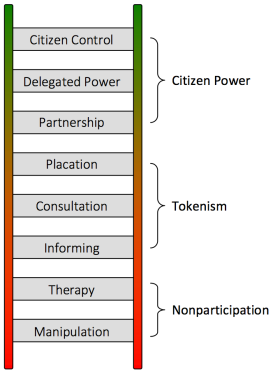

The government’s welfare “reforms” have already invited scathing international criticism because they have disproportionately targeted cuts at those with the least income. Furthermore, the government have systematically violated the human rights of those with mental and physical disabilities. In a highly critical UN report which followed a lengthy inquiry, it says: “States parties should find an adequate balance between providing an adequate level of income security for persons with disabilities through social security schemes and supporting their labour inclusion. The two sets of measures should be seen as complementary rather than contradictory.”

However, the UK government have continued to conflate social justice and inclusion with punitive policies and cuts – dressed up in the language of “incentives” and “nudge” – aimed at coercing disabled people towards narrow employment outcomes that preferably bypass any form of genuine support and the social security system completely. (See –UN’s highly critical report confirms UK government has systematically violated the human rights of disabled people).

It’s hardly the case that the state has an even remotely credible track record of assessing people’s medical conditions, nor is it the case that this government bothers itself with empirical evidence, or deigns to listen to concerns raised by citizens, academics, professionals and charities regarding the harm that their policies are causing. This is a government that can’t even manage to observe basic human rights, let alone care about citizen’s best interests, health and wellbeing. In a political context of savage cuts to essential support and services for disabled people, and such blatant disregard of the legislative frameworks that outline their fundamental rights, it is very difficult to trust that this government have the best interests of disabled people in mind with the formulation of Work, Health and Employment related programmes.

The government’s aim to prompt public services to “speak with one voice” to promote work as a health outcome is founded on highly questionable ethics. This proposed multi-agency approach is reductive, rather than being about formulating expansive, coherent, comprehensive and importantly, responsive provision.

Employment is not therapy. Ultimately, the IPS programme is all about (re)defining the behaviours, experience and reality of a social group to ensure they conform to government ideological incentives and to justify dismantling public services (especially welfare, and increasingly, the NHS – see, for example, Rogue company Unum’s profiteering hand in the government’s work, health and disability green paper).

This is form of gaslighting intended to extend oppressive political control and behavioural micromanagement. In linking receipt of welfare with health services and “state therapy,” with the single intended outcome explicitly expressed as employment, the government is purposefully conflating citizen’s widely varied needs with economic outcomes and diktats, isolating people from traditionally non-partisan networks of relatively unconditional support, such as the health service, social services, community services and mental health services.

Public services “speaking with one voice” will invariably make accessing support conditional, and further isolate already marginalised social groups. It will damage trust between people needing support and professionals who are meant to deliver essential public services, rather than simply extending government dogma, prejudices and discrimination.

Conservatives really seem to believe that the only indication of a person’s functional capacity, value and potential is their economic productivity, and the only indication of their moral worth is their capability and degree of willingness to work. But unsatisfactory employment – low-paid, insecure and unfulfilling work – can result in a decline in health and wellbeing, indicating that it is poverty and growing inequality, rather than unemployment, that increases the risk of experiencing poor mental and physical health.