“Behavioural theory is a powerful tool for the government communicator, but you don’t need to be an experienced social scientist to apply it successfully to your work.”

Alex Aiken

Executive Director of

Government Communications (Source).

Introduction

The Conservatives have always used emotive and morally-laden narratives that revolve around notions of “national decline” and a “broken society” to demarcate “us and them”, using overly simplistic binary schema. Conservative rhetoric reflexively defines what the nation is and who it excludes, always creating categories of others.

David Cameron’s government have purposefully manufactured a minimal group paradigm which is founded on a false dichotomy. People who “work hard” are deemed “responsible” citizens and the rest are stigmatized, labelled as “scroungers” and outgrouped (inaccurately) as irresponsible economic free riders. This prejudiced distinction requires a single snapshot of just one frozen point in time, and an assumption that people who claim welfare support are the same people year after year, but longitudinal studies indicate that over the course of their lives, most people move in and out of employment. Most people claiming welfare support have worked and made responsible contributions to society.

The Conservatives also claim that welfare provision itself is problematic, because it creates “a culture of dependency.” Yet there has never been evidence to support this claim. In fact, a recent international study of social safety nets from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard economists refutes the Conservative “scrounger” stereotype and dependency rhetoric. Abhijit Banerjee, Rema Hanna, Gabriel Kreindler, and Benjamin Olken re-analyzed data from seven randomized experiments evaluating cash programmes in poor countries and found “no systematic evidence that cash transfer programmes discourage work.”

The phrase “welfare dependency” was designed to intentionally divert attention from political prejudice, discrimation via policies and to disperse public sympathies towards the poorest citizens.

The Conservatives have always constructed discourses and shaped institutions which isolate some social groups from health, social and political resources, with justification narratives based on a process of class-contingent personalisations of social problems, such as poverty, using quack psychology and pseudoscience. However, it is social conditions which lead to deprivation of opportunities, and that outcome is a direct consequence of inadequate and biased political decision-making and policy.

Conditionality

One of the uniquely important features of Britain’s welfare state is the National Insurance system, based on the principle that people establish a right to benefits by making regular contributions into a fund throughout their working lives. The contribution principle has been a part of the welfare state since its inception. A system of social security where claims are, in principle, based on entitlements established by past contributions expresses an important moral rule about how a benefits system should operate, based on reciprocity and collective responsibility, and it is a rule which attracts widespread public commitment. National Insurance is felt intuitively by most people to be a fair way of organising welfare.

The Conservative-led welfare “reforms” had the stated aim of ensuring that benefit claimants – redefined as an outgroup of free-riders – are entitled to a minimum income provided that they uphold responsibilities, which entail being pushed into any available work. The Government claim that sanctions “incentivise” people to look for employment.

Conditionality for social security has been around as long as the welfare state. Eligibility criteria have always been an intrinsic part of the social security system. For example, to qualify for jobseekers allowance, a person has to be out of work, able to work, and seeking employment.

But in recent years conditionality has become conflated with severe financial penalities (sanctions), and has mutated into an ever more stringent, complex, demanding set of often arbitrary requirements, involving frequent and rigidly imposed jobcentre appointments, meeting job application targets, providing evidence of job searches and mandatory participation in workfare schemes. The emphasis of welfare provision has shifted from providing support for people seeking employment to increasing conditionality of conduct, enforcing particular patterns of behaviour and monitoring claimant compliance.

Sanctions are “penalties that reduce or terminate welfare benefits in cases where claimants are deemed to be out of compliance with requirements.” They are, in many respects, the neoliberal-paternalist tool of discipline par excellence – the threat that puts a big stick behind coercive welfare programme rules and “incentivises” citizen compliance with a heavily monitoring and supervisory administration. The Conservatives have broadened the scope of behaviours that are subject to sanction, and have widened the application of sanctions to include previously protected social groups, such as ill and disabled people, pregnant women and lone parents.

The new paternalists often present their position as striking a moderate, reasonable middle ground between rigid anti-paternalism on the one hand and an overly intrusive “hard” paternalism on the other. But the claim to moderation is difficult to sustain, especially when we consider the behavioural modification technique utilised here – punishment – and the consequences of sanctioning welfare recipients, many of whom are already struggling to meet their basic needs.

Nudge permits policy-makers to indulge their ideological impulses whilst presenting them as “objective science.” From the perspective of libertarian paternalists, the problems of neoliberalism don’t lie in the market, or in growing inequality and social stratification: neoliberalism isn’t flawed, nor are governments – we are. Governments don’t make mistakes – only citizens do.

Work programme providers are sanctioning twice as many people as they are signposting into employment (David Etherington, Anne Daguerre, 2015), emphasising the distorted priorities of “welfare to work” services, and indicating a significant gap between claimant obligations and employment outcomes.

Ethical considerations of injustice and the adverse consequences of welfare sanctions have been raised by politicians, charities, campaigners and academics. Professor David Stuckler of Oxford University’s Department of Sociology, among others, has found clear evidence of a link between people seeking food aid and unemployment, welfare sanctions and budget cuts, although the government has, on the whole, tried to deny a direct “causal link” between the harsh welfare “reforms” and food deprivation. However, a clear correlation has been established.

The current government demand an empirical rigour from those presenting legitimate criticism of their policy, yet they curiously fail in meeting the same exacting standards that they demand of others. Often, the claim that “no causal link has been established” is used as a way of ensuring that established, defined correlative relationships, (which often do imply causality,) are not investigated further. Qualitative evidence – case studies, for example – is very often rather undemocratically dismissed as “anecdotal,” which of course stifles further opportunities for important research and inquiry regarding the consequences and impacts of government policy. This also undermines the process of a genuine evidence-based policy-making, leaving a space for a rather less democratic ideology-based political decision-making.

Further concerns have arisen that food banks have become an institutional part of our steadily diminishing welfare state, normalising food insecurity and deprivation among people both in and out of work.

There is no evidence that keeping benefits at below subsistence level “incentivises” people to work. In fact research indicates it is likely to have the opposite effect. In 2010/2011, 61,468 people were given 3 days emergency food and support by the Trussell Trust and this rose to 913,138 people in 2013-2014.

At least four million people in the UK do not have access to a healthy diet; nearly 13 million people live below the poverty line, and it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to afford food. More than half a million children in the UK are now living in families who are unable to provide a minimally acceptable, nutritious diet. (Source: Welfare Reform, Work First Policies And Benefit Conditionality: Reinforcing Poverty And Social Exclusion? – Centre for Enterprise and Economic Development Research, 2015.)

There is plenty of evidence that sanctions don’t help people to find work, and that the punitive application of severe financial penalties is having an extremely detrimental, sometimes catastrophic impact on people’s lives. We can see from a growing body of research how sanctions are not working in the way the government claim they intended.

Sanctions, under which people lose benefit payments for between four weeks and three years for “non-compliance”, have come under fire for being unfair, punitive, failing to increase job prospects, and causing hunger, debt and ill-health among jobseekers. And sometimes they result in death.

I want to discuss two further considerations to add to growing criticism of the extended use of sanctioning which are related to why sanctions don’t work. One is that imposing such severe financial penalties on people who need social security support to meet their basic needs cannot possibly bring about positive “behaviour change” or “incentivise” people to find employment, as claimed. This is because of the evidenced and documented broad-ranging negative impacts of financial insecurity and deprivation – particularly food poverty – on human physical health, motivation, behaviour and mental health.

The second related consideration is that “behavioural theories” on which the government rests the case for extending and increasing benefit sanctions, are simply inadequate and flawed, having been imported from a limited behavioural economics model (otherwise known as libertarian paternalism) which is itself ideologically premised.

At best, the new “behavioural science” is merely a set of theoretical propositions, at a broadly experimental stage, and therefore profoundly limited in terms of scope and academic rigour. As a mechanism of explanation, it is lacking in terms of capacity for generating comprehensive, coherent accounts and understanding about human motivation and behaviour.

Furthermore, in relying upon a pseudo-positivistic experimental approach to human cognition, behavioural economists have made some highly questionable ontological and epistemologial assumptions: in the pursuit of methodological individualism, citizens are consequently isolated from the broader structural political, economic, sociocultural and established reciprocal contexts that invariably influence and shape an individual’s experiences, meanings, motivations, behaviours and attitudes, causing a problematic duality between context and cognition. The libertarian paternalist approach also places unfair and unreasonable responsibility on citizens for circumstances which lie outside of their control, such as the socioeconomic consequences of political decision-making.

Yet many libertarian paternalists reapply the context they evade in explanations of human behaviours to justify the application of their theory, claiming that their collective “behavioural theories” can be used to serve social, and not necessarily individual ends, by simply acting upon the individual to make them more “responsible.” (See, for example: Personal Responsibility and Changing Behaviour: the state of knowledge and its implications for public policy, David Halpern, Clive Bates, Geoff Mulgan and Stephen Aldridge, 2004.)

In other words, there is a relationship between the world that a person inhabits and that person’s actions. Any theory of behaviour and cognition that ignores context can at best be regarded as very limited and partial. Yet the libertarian paternalists overstep their narrow conceptual bounds, with the difficulty of reconciling individual and social interests glossed over somewhat.

The ideological premise on which the government’s “behavioural theories” and assumptions about unemployed and ill and disabled people rests is also fundamentally flawed. Neoliberalism and social Conservatism are not working to extend wealth and opportunity to a majority of citizens. The shift away from a collective rights-based democratic society to a state-imposed moral paternalism, comprised almost entirely of unfunded, unsupported, decontextualised “responsible” individuals is simply an ideological edit of reality, hidden in plain sight within the tyranny of decision-makers deciding and shaping our “best interests”, to justify authoritarian socioeconomic policies that generate and perpetuate inequality and poverty. Libertarian paternalists don’t have much of a vocabulary for discussing any sort of collective, democratic, or autonomous and deliberative decision-making.

The Conservatives and a largely complicit media convey the message that poor people suffer from some sort of character flaw – a poverty of aspiration, a deviance from the decent, hard-working norm. That’s untrue, of course: poor people simply suffer from material poverty which may steal motivation and aspiration from any and every person that is reduced to struggling for basic survival.

It’s not a coincidence that those countries with institutions designed to alleviate poverty and inequality – such as a robust welfare state, a strong role for collective bargaining, a stronger tax and transfer system, have lower levels of income inequality and poverty.

—

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment volunteers

1. “Starved people can’t be taught democracy.” Ancel Keys

Imposing punishment in the form of financial sanctions on people who already have only very limited resources for meeting their basic survival needs is not only irrational, it is absurdly and spectacularly cruel. There is a body of evidence from a landmark study that describes in detail the negative impacts of food deprivation on physical and psychological health, including an account of the detrimental effects of hunger on motivation and behaviour.

During World War Two, many conscientious objectors wanted to contribute to the war effort meaningfully, and according to their beliefs. In the US, 36 conscientious objectors volunteered for medical research as an alternative to military service. The research was designed to explore the effects of hunger, to provide postwar rehabilitation for the many Europeans who had suffered near starvation and malnutrition during the war.

A high proportion of the volunteers were members of the historic peace churches (Brethren, Quakers, and Mennonites). The subjects, all healthy males, participated in a study of human semistarvation conducted by Ancel Keys and his colleagues at the University of Minnesota. The Minnesota Starvation Experiment, as it was later known, was a grueling six month study designed to gain insight into the physical and psychological effects of food deprivation. Those selected to participate in the experiment were a highly motivated and well-educated group; all had completed some college coursework, 18 had graduated, and a few had already begun graduate-level coursework.

The Minnesota laboratory

During the experiment, the participants were subjected to semistarvation, most lost 25% of their body weight in total. The participants underwent extensive tests throughout the experiment. Body weight, size, and strength were recorded, and basic functions were tracked using X-rays, electrocardiograms, blood samples, and metabolic studies. Psychomotor and endurance tests were given, as the men walked on the laboratory treadmills, and participants received intelligence and personality tests from a team of psychologists.

The men ate meals twice a day. Typical meals consisted of cabbage, turnips and half a glass of milk. On another day, it might be rye bread and some beans. Keys designed the meals to be carbohydrate rich and protein poor, simulating what people in Europe might be eating, with an emphasis on potatoes, cabbage, macaroni and whole wheat bread (all in meagre proportions). Despite the reduction in food, Keys insisted that the men try to maintain their active lifestyle, including the 22 miles of walking each week.

The negative effects of the reduced food intake quickly became apparent. The men rapidly showed a remarkable decline in strength and energy. Keys charted a 21 per cent reduction in their physical strength, as measured by their performance, using a variety of methods, including a back lift dynamometer. The men complained that they felt old and constantly tired.

There were marked psychological effects, too. They developed a profound mental apathy. The men had strong political opinions, but as the grip of hunger tightened, political affairs and world events faded into irrelevance for them. Even sex and romance lost their appeal. Food became their overwhelming priority. The men obsessively read cookbooks, staring at pictures of food with almost pornographic obsession. One participant managed to collect over a 100 cookbooks with pictures over the course of the experiment.

Some subjects diluted their food with water to make the meagre proportions seem like more. Others would savour each little bite and hold it in their mouth as long as possible. Eating became ritualised and took a long time.

One of the volunteers recalled memorising the location of all of the lifts in the university buildings because he struggled climbing stairs, and even experienced difficulty opening doors, he felt so weak. The researchers recognised that “energy is a commodity to be hoarded – living and eating quarters should be arranged conveniently” in a subsequent leaflet designed to help in accommodating the increasing weakness and lethargy in people needing aid and support to recover from semistarvation.

Within just a few weeks of the study, the psychological stress that affected all of the subjects became too much for one of the men, Franklin Watkins. He had a ‘breakdown’ after having vivid, disturbing dreams of cannibalism in which he was eating the flesh of an old man. He had to leave the experiment. Two more subjects also suffered severe psychological distress and episodes of psychosis during the semistarvation period, resulting in brief stays in the psychiatric ward of the Minnesota university hospital. One of the men had also reported stealing scraps of food from bins.

Among the conclusions from the study was the confirmation that prolonged semistarvation produces significant increases in depression, ‘hysteria’ and ‘hypochondriasis’, which was measured using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. Most volunteers experienced periods of severe emotional distress and depression. There were extreme reactions to the psychological effects during the experiment including self-mutilation (one subject amputated three fingers of his hand with an axe, though the subject was unsure if he had done so intentionally or accidentally.)

The men also became uncharacteristically irritable, introverted and argumentative towards each other, they became less sociable, experiencing an increasing need for privacy and quiet – noise of all kinds seemed to be very distracting and bothersome and especially so during mealtimes. The men became increasingly apathetic and frequently depressed.

The volunteers reported decreased tolerance for cold temperatures, and requested additional blankets, even in the middle of summer. They experienced dizziness, extreme tiredness, muscle soreness, hair loss, reduced coordination, and ringing in their ears. They were forced to withdraw from their university classes because they simply didn’t have the energy or motivation to attend and to concentrate. Other recorded problems were anemia, profound fatigue, apathy, extreme weakness, irritability, neurological deficits, and lower extremity fluid retention, slowed heart rate among other symptoms.

The Minnesota Experiment also focused study on attitudes, cognitive and social functioning and the behaviour patterns of those who have experienced semistarvation. The experiment illuminated a loss of ambition, self-discipline, motivation and willpower amongst the men once food deprivation commenced. There was a flattening of affect, and in the absence of all other emotions, Doctor Keys observed the resignation and submission that hunger very often manifests.

The understanding that food deprivation dramatically alters emotions, motivation, personality, and that nutrition directly and predictably affects the mind as well as the body is one of the legacies of the experiment.

In the last months of the experiment, the volunteers were fed back to health. Different groups were presented with different foods and calorie allowances. But it was months, even years – long after the men had returned home – before they had all fully recovered. Keys published his full report about the experiment in 1950. It was a substantial two-volume work titled The Biology of Human Starvation. To this day, it remains the most comprehensive scientific examination of the physical and psychological effects of hunger.

Keys emphasised the dramatic effect that semistarvation had on motivation, mental attitude and personality, and he concluded that democracy and nation building would not be possible in a population that did not have access to sufficient food.

—

2. Abraham Maslow and the hierarchy of human needs

“It is quite true that man lives by bread alone – when there is no bread.”

Maslow was humanist psychologist. He proposed his classical theory of motivation and the hierarchical nature of human needs in 1943. His critical insights have been translated into an iconic pyramid diagram, which depicts the full spectrum of needs, ranging from physical to psychosocial. Maslow believed that people possess a set of simple motivation systems that are unrelated to the punishments and rewards that behaviourists proposed, or the complexities of unconscious desires proposed by the psychoanalysts.

Maslow said basically that the imperative to fulfil basic needs will become stronger the longer the duration that they are denied. For example, the longer a person goes without food, the more hungry and preoccupied with food they will become.

So, a person must satisfy lower level basic biological needs before progressing on to meet higher level personal growth needs. A pressing need would have to be satisfied before someone would give their attention to the next highest need. If a person has not managed to meet their basic physical needs, it’s highly unlikely that they will be motivated to fulfil higher level psychosocial ones.

Maslow recognised that although every human is capable and has the desire to move up the hierarchy of needs to fulfil their potential, progress is often disrupted by a failure to meet lower level needs. Life experiences, including the loss of a job, loss of a home, poverty, illness, for example, may cause an individual to become trapped at the lower needs levels of the hierarchy.

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs

Some theorists have claimed that while Maslow’s hierarchy makes sense – it’s founded on an intuitive truth – it lacks scientific support. However, Maslow’s theory has certainly been verified by the findings of the Minnesota Experiment and other studies of the effects of food deprivation. Abraham Maslow’s humanist account of motivation also highlights the same connection between fundamental motives and immediate situational threats.

The experiment highlighted a striking sense of immediacy and fixation that arises when there are barriers to fulfilling basic physical needs – human motivation is frozen to meet survival needs, which take precedence over all other needs. This is observed and reflected in both the researcher’s and the subject’s accounts throughout the study. If a person is starving, the desire to obtain food will trump all other goals and dominate the person’s thought processes. This idea of cognitive priority is also clearly expressed in Maslow’s needs hierarchy.

In a nutshell, this means that if people can’t meet their basic survival needs, it is extremely unlikely that they will have either the capability or motivation to meet higher level psychosocial needs, including social obligations and responsibilities to seek employment.

—

Conclusions: the poverty of responsibility and the politics of blame

American Conservative academic, Lawrence Mead, argued in 2010 that the government needed to “enforce values that have broken down” such as the “work ethic”, with an expensive, intrusive bureaucracy that “helped and hassled” people back to work. Mead was a Conservative political “scientist” who said that poverty was largely due to a breakdown of public authority. Poverty reflected disorder more than denials of opportunity. He felt that the poor were “too free,” rather than not free enough.

He believed that benefits should be “mean and conditional,” forcing recipients to take any available jobs. Calling himself a “new paternalist”, his proposal is that people must be taught to blame themselves for their hardships and accept that they deserve them. He believed that workfare should be an onerous threat, so that people opt out of the social security system altogether. (See: Guardian, June 16, 2010). Mead provided the theoretical basis for the American welfare reforms of the 1990s, which required adult recipients of welfare to work as a condition of aid.

The consequences of the US reforms have been dire for many families, both in and out of work. Many are now facing destitution as a consequence of the US welfare safety net being cut away. Mead also considerably influenced the UK Conservative-led welfare reforms.

The extremely conditional welfare approach that Mead advocated rests on the assumption that the problems it seeks to address are fundamentally behavioural in nature (rather than structural) and are therefore amenable to remedy through paternalist punishment, or, to borrow from the libertarian paternalist bland lexicon, through manipulation of “cognitive biases“, in this case, one specifically known as loss aversion.

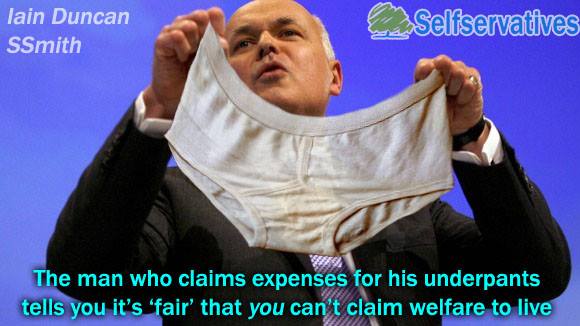

A paper, written in 2010 – Applying behavioural economics to welfare to work – contained outlines of the pseudo-psychological justification for increasing the use of sanctions. The “research” was sponsored by Steve Moore, Business Development Director of esg , a key welfare to work consortium, which was established by two Tory donors with close ties to ministers. The Government’s Behavioural Insights Team (the “Nudge” Unit) provided a tenuous theoretical framework and a psychobabbled rationale for increasing and extending the use of benefit sanctions, transforming welfare provision into a system of directed political prejudice, discrimination and punishment.

The following year, in June, the government announced that it would toughen the sanctions regime, making it much more difficult for claimants to temporarily sign off benefits to avoid being forced into unpaid work. Perhaps the woefully under-recognised and under-acknowledged cognitive bias called “vested interests“ escaped the attention of libertarian paternalists, when esg were awarded two extremely lucrative government contracts with Iain Duncan Smith’s Department for Work and Pensions in 2011, which amounted to £73million.

So, the paper provides a justification narrative for welfare sanctions and mandatory work fare, and it also preempts an opportunity for work fare providers to make lots of profit and to subsidise private businesses with free labor at the expense of the UK’s poorest citizens and taxpayers. Yet the government’s own research also showed that the scheme does not help unemployed people to find paid employment once they have finished the four weeks of mandatory work “experience”. It also has no positive effect in “helping people off benefits” and into employment in the long term.

The libertarian paternalist justification narrative is basically a pseudoscientific attempt to pathologise and homogenise the psychology of unemployed people, justifying the need for a very lucrative “remedy,” which is costing the poorest citizens their autonomy, health and wellbeing. It’s also costing the public purse far more than it would to simply provide social security for people needing support in meeting their basic needs.

Furthermore, as I have previously pointed out, it flies in the face of established empirical evidence.

From the document in 2010, on page 18: “The most obvious policy implication arising from loss aversion is that if policy-makers can clearly convey the losses that certain behaviour will incur, it may encourage people not to do it.” This of course assumes that being without a job is because of nothing more complex than opting for a “lifestyle choice.”

And page 46: “Given that, for most people, losses are more important than comparable gains, it is important that potential losses are defined and made explicit to jobseekers (e.g.the sanctions regime).”

The recommendation on page 46: “We believe the regime is currently too complex and, despite people’s tendency towards loss aversion, the lack of clarity around the sanctions regime can make it ineffective. Complexity prevents claimants from fully appreciating the financial losses they face if they do not comply with the conditions of their benefit.”

The Conservatives subsequently “simplified” sanctions by extending their use to previously protected groups, such as ill and disabled people and lone parents, increasing their severity and increasing the frequency of their use from 2012.

Of course there is a problem in assuming that punishing people will make them behave more “rationally,” and that is aside from the ethical dilemmas presented with neoliberal paternalists and businesses deciding what is “rational” and in other people’s “best interests.”

Deprivation substantially increases the risk of mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, depression, anxiety and substance addiction. Poverty can act as both a causal factor (e.g. stress resulting from poverty triggering depression) and a consequence of mental illness (e.g. schizophrenic symptoms leading to decreased socioeconomic status and prospects).

Poverty is a significant risk factor in a wide range of psychological illnesses. Researchers recently reviewed evidence for the effects of socioeconomic status on three categories: schizophrenia, mood and anxiety disorders and substance abuse. While not a comprehensive list of conditions associated with poverty, the issues raised in these three areas can be generalised, and have clear relevance for policy-makers.

The researchers concluded: “Fundamentally, poverty is an economic issue, not a psychological one. Understanding the psychological processes associated with poverty can improve the efficacy of economically focused reform, but is not a panacea. The proposals suggested here would supplement a focused economic strategy aimed at reducing poverty.” (Source: A review of psychological research into the causes and consequences of poverty, Ben Fell, Miles Hewstone, 2015.)

The Conservative shift in emphasis from structural to psychological explanations of poverty has far-reaching consequences. The recent partisan reconceptualision of poverty makes it much more difficult to define and measure. Such a conceptual change disconnects poverty from more than a century of detailed empirical and theoretical research, and we are witnessing an increasingly experimental approach to policy-making, as opposed to an evidence-based one, aimed solely at changing the behaviour of individuals, (to meet the demands of policy-makers) without their consent.

At least the Treasury is benefiting from the new conditionality and sanctions regime. Earlier this year, the Work and Pensions select committee heard independent estimates (committee member Debbie Abrahams MP said the DWP will not give or does not have figures) that since late 2012 sanctions had resulted in at least £275m being withheld from benefit claimants (the comparable figure for 2010 was £50m).

Many people in work are still living in poverty and reliant on in-work benefits, which undermines the libertarian paternalist case for increasing benefit conditionality somewhat, although those in low-paid work are still likely to be less poor than those reliant on out-of-work benefits. The Conservative “making work pay” slogan is a cryptographic reference to the punitive paternalist 1834 Poor Law principle of less eligibility.

But part of the government’s Universal Credit legislation is founded on the idea that working people in receipt of in-work benefits may face punitive benefits sanctions if they are deemed to be not trying hard enough to find higher paid work. It’s not as if the Conservatives have ever valued legitimate collective wage bargaining. In fact their legislative track record consistently demonstrates that they hate it, prioritising the authority of the state above all else.

Workplace disagreements about wages and conditions are now typically resolved neither by collective bargaining nor litigation but are left to management prerogative. Conservative aspirations are clear. They want cheap labor and low cost workers, unable to withdraw their labor, unprotected by either trade unions or employment rights and threatened with destitution via benefit sanction cuts if they refuse to accept low paid, low standard work. This is thought to “increase economic competitiveness.” Similarly, desperation and the “deterrent” effect of the 1834 Poor Law amendment served to drive down wages. In the Conservative’s view, trade unions distort the free labor market, which runs counter to New Right and neoliberal dogma.

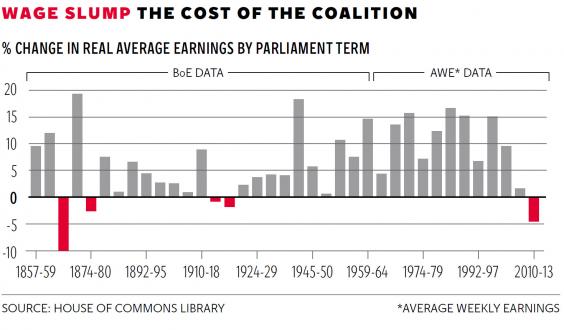

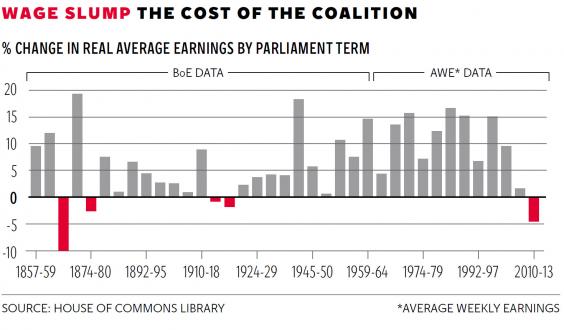

Since 2010, the decline in UK wage levels has been among the very worst in Europe. The fall in earnings under the Coalition is the biggest in any parliament since 1880, according to analysis by the House of Commons Library, and at a time when the cost of living has spiralled upwards.

There has been a powerful shift back from progressive notions of collective social justice and equality to increasingly absurd, unfair and enforced individual responsibilities without concomitant rights, the underpinning Conservative view is that that socioeconomic inequality resulting from the free market is necessary and not something that the state need or should do anything about. Inequality in the UK is now greater than in any other European Union country, and including in the US. Yet the subsequent growing poverty and uncertainties of the labor market are irrationally held to be the responsibility of the individual.

In fact the state is forcefully redistributing the risks and burdens of job-market instability from the state to unemployed individuals. The “problem” of an entirely politically-defined “welfare dependency” is presented with a “solution” in terms of a one-way transition into low-waged, poor quality work, which does not alleviate poverty.

Any analysis of the British economy over the past 40 years shows how the decline of union power since the early 1980s has coincided with the fall in the proportion of GDP that goes to wages, and the rise of private business profits. Boardroom pay has sky-rocketed whilst wages have been held down, as chief executives and directors no longer fear the effect of their pay rises on their staff. It’s a neoliberal myth that if firms are profitable, they are more likely to employ more workers, or that falling profitability is likely to reduce the demand for labor. One problem is that the government and employers have come to see the workforce as a disposable cost rather than an asset.

Wage repression has nothing whatsoever to do with workers, and threatening to punish low paid workers for their employer’s profit motive and the vagaries of an unregulated (liberalised) labor market by removing the in-work benefits that ensure exploited workers don’t face destitution is not only absurd, it is extremely cruel. The steady erosion of the post-war welfare state, and the increasing use of punitive approaches has served to further facilitate private sector wage repression. Nineteenth century notions of punitive deterrence have replaced civilised notions of citizen rights and entitlement, once again penalising people for the manifested symptoms but sidestepping the root causes of poverty.

Libertarian paternalist nudges may only work by stigmatising particular behaviours. The new “behavioural science” reflects an ideological and cultural rejuvenation of the Conservative’s ancient moral and prejudiced critique of the poor, polished by nothing more than pseudoscientific attempts at erecting a stage of credibility, using a kind of linguistic alchemy, based on purposefully manufactured semantic shifts and bland, meaningless acronyms.

What was once summarily dismissed from Victorian moralists such as Samuel Smiles, and Herbert Spencer, who is best known for the expression, and sociopolitical application of the social Darwinist phrase survival of the fittest, is now being recodified into the bland terminology and inane managementspeak acronyms emanating from the behavioural economics “insights” team – the semi-privatised Nudge Unit at the heart of the Cabinet Office.

This was the race to the bottom situation for many people in Victorian England, where conditions in the workhouses became appalling because conditions for unskilled workers were also appalling. It established a kind of market competition situation of the conditions of poverty, where “making work pay” invariably means never-ending reductions in the standard of living for unemployed people and those in low paid work. Benefit sanctions amount to cutting unemployment benefits, reducing choices by forcing people into any available low paid employment and have exactly the same effect: they drive down wages and devalue labour.

Narratives are representations of connected events and characters that have an identifiable structure, and contain implicit or explicit messages about social norms, and the topic being addressed as such may impact attitudes and behaviour. One way to shift perceptions and “change behaviours”, according to the new ‘economologists’, is through intensive social norms media campaigns. Media narratives are being nudged, too.

From MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy, David Halpern et al (2010):

“Framing is crucial when attempting to engage the public with behaviour change.”

“There are ways in which governments can boost their authority, and minimise psychological reactance in the public.”

“Sometimes campaigns can increase perceptions of undesirable behaviour.”

Research shows that public ideas about poverty and unemployment depend heavily on how the issues are framed. When news media presentations frame poverty, for example, in terms of general outcome, people tend to believe that society collectively shares the responsibility for poverty. When poverty is framed as particular instances of individual poor people, responsibility is assigned to those individuals. In 1986, The General Social Survey documented how various descriptions of poor families influence the amount of assistance that people think they ought to have. Political framing is a powerful tool of social control. It agendarises issues (according to a dominant and Conservative economic, moral and social system that values thrift and moderation in all things, but mostly for the poorest people) and establishes the operational parameters of public debate.

The most controversial government policies are, to a large extent, reliant on dominant media narratives and images for garnering public endorsement. Prevailing patterns have emerged that systematically and intentionally stigmatise and scapegoat unemployed citizens, framing inequality and poverty as “causally linked” with degrees of personal responsibility, which is then used as a means of securing public acceptance for “rolling back the state.” News media define political issues for much of the public, and set simplistic access levels, often reducing complex issues to basic dichotomies – and establishing default settings, to borrow from the lexicon of libertarian paternalists. Default settings allow policy-makers to shift the goalposts, and align public attitudes and behaviours with new policy objectives and outcomes. And ideology.

For example, one established default setting, is that hard work, regardless of how appropriate or rewarding, is the only means of escaping poverty. A variety of methods have been used to establish this, although the new paternalists tend to rely heavily on notions of political authority to manipulate social norms, the mainstream media has played a significant role in extending and propping up definitions of an ingroup of “hardworking families,” while othering, pathologising and outgrouping categories of persons previously considered exempt from employment, such as chronically ill and disabled people and lone parents.

The perpetual circulation of media images and discourse relating to characters pre-figured as welfare dependents, and accounts of the notion of a spiralling culture of dependency this past five years closely correspond with New Right narratives.

The marked shift from the principle of welfare provision on the basis of need to one that revisits nineteenth century notions of “deservingness” as a key moral criterion for the allocation of societal goods, with deservingness defined primarily in relation to preparedness to make societal contribution via paid work is likely to widen inequality. In fact behaviour theory approaches to policy simply prop up old Conservative prejudices about the nature of poverty, and provide pseudoscientific justification narratives for austerity, neoliberal and Conservative ideology. As such, nudge is revealed for what it is: an insidious form of behaviourism: operant conditioning; social engineering and the targeted and class-contingent restriction of citizen autonomy.

There are many examples on record of sanctions being applied unfairly, and of the devastating impact that sanctions are having on people who need to claim social security. Dr David Webster of Glasgow University has argued that benefit claimants are being subjected to an “amateurish, secret penal system which is more severe than the mainstream judicial system,” and that “the number of financial penalties (sanctions) imposed on benefit claimants by the Department of Work and Pensions now exceeds the number of fines imposed by the courts.

Furthermore, decisions on the “guilt” of noncompliance” are made in secret by officials who have no independent responsibility to act lawfully. Professor Michael Adler has raised concern that benefit sanctions are incompatable with the rule of law.

There is no doubt that sanctions are regressive, taking income that is designed to meet basic survival needs from families and individuals who are already very resource-constrained, is particularly draconian. But even by the proclaimed standards of the Department for Work and Pensions, sanctions are being applied unfairly, it’s a policy that has been based on discretionary arbitrary judgments, and the injustice and adverse consequences of welfare sanctions make their continued use untenable. As well as having clearly detrimental material and biological impacts, sanctions have unsurprisingly been associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes, increased stress and reduced emotional wellbeing recently, once again. (Dorsett, 2008; Goodwin, 2008; Griggs and Evans, 2010).

There has been a wealth of evidence that refutes the Conservative claim that benefit sanctions “incentivise” people and “help” them into employment. There is a distinction between compliance with welfare conditionality rules, off-flow measurement and employment. Furthermore, there is no evidence that applying behaviourist principles to the treatment of people claiming social security, any subsequent behaviour change and positive employment outcomes are in any way correlated.

Sanctions don’t work, and the politics of punishment has no place in a so-called civilised society

The Conservative government have taken what can, at best, be described as an ambivalent attitude to evidence-gathering and presentation to support their claims to date. There is no evidence that welfare sanctions improve employment outcomes. There is no evidence that sanctions “change behaviours.”

There is, in any case, a substantial difference between people conforming with welfare conditionality and rules, and gaining appropriate employment. And a further distinction between compliance and conversion. One difficulty is that since 2011, Job Centre Plus’s (JCP) primary key performance indicator has been off-flow from benefit at the 13th, 26th, 39th and 52nd weeks of claims. Previously JCP’s performance had been measured against a range of performance indicators, including off-flows from benefit into employment.

Indeed, when asked for evidence by the Work and Pensions Committee, one minister, in her determination to defend the Conservative sanction regime, regrettably provided misleading information on the destinations of JSA, Income Support and Employment Support Allowance claimants from 2011, that pre-dated the new sanctions regime introduced in 2012, in an attempt to challenge the findings of the University of Oxford/LSHTM study on the effects of sanctions on getting JSA claimants off-flow. (Fewer than 20 per cent of this group of people who were no longer in receipt of JSA were recorded as finding employment.) Source: Benefit sanctions policy beyond the Oakley Review – Work and Pensions.

National Assistance Scales were originally based on specialist calculation of the cost of a “basket of essential goods” necessary to sustain life that were devised by Seebohm Rowntree for Sir William Beveridge when he founded the Welfare State in the 1940s. Rowntree fixed his primary poverty threshold, in his pioneering study of poverty in York (1901), as the income required to purchase only physical necessities. The scales were devised to determine levels of support for unemployed people, sick and disabled people, and those who had retired or were widowed.

Rowntree’s research helped to advance our understanding of poverty. For example, he discovered that it was caused by structural factors – resulting from unemployment and low wages, in 1899 – and not behavioural factors. Rowntree and Laver cited full employment policies, rises in real wages and the expansion of social welfare programmes as the key factors behind the significant fall in poverty by the 1950s. They could also demonstrate that, while 60% of poverty in 1936 was caused by low wages or unemployment, the corresponding figure by 1950 was only 1%. But we have witnessed a regression since Thatcher’s New Right era, and continue to do so because of an incoherent Conservative anti-welfare ideology, scapegoating narratives and neoliberal approaches to dismantling the social gains of the post-war democratic settlement.

Yet Rowntree’s basic approach to defining and addressing poverty remains unchallenged, both in terms of its empirical basis and in terms of positive social outcomes. There is categorically no doubt that human beings have to meet physical needs, having access to fundamental necessities such as food, fuel, clothing and shelter, for survival.

There is a weight of empirical evidence confirming that food deprivation is profoundly psychologically harmful as much as it is physiologically damaging. If people can’t meet their basic survival needs, it is extremely unlikely that they will either have the capability or motivation to meet higher level psychosocial needs, including social obligations, fulfilling responsibilities to find work and to meet conditionality requirements.

There is a clear relationship between human needs, human rights, and social justice. Needs are an important concept that guide empowerment based practices and the concept is intrinsic to social justice. Furthermore, the meeting of physiological and safety needs of citizens ought to be the very foundation of economic justice as well as the development of a democratic society.

An elitist, technocratic government that believes citizens are not reliably competent thinkers will treat those citizens differently to one that respects their reflective autonomy. Especially a government that has decided in the face of a history of contradictory evidence, that the “faulty behaviour” and decision-making of individuals is the cause of social problems, such as inequality, poverty and unemployment.

Sanctioning people who need financial support to meet their basic needs is cruel and can never work to “incentivise” people to “change their behaviours.” One reason is that poverty is not caused by the behaviour of poor people. Another is that sanctions work to demotivate and damage people, creating further perverse barriers to choices and opportunities, as well as stifling human potential.

Earlier this year, the Work and Pensions Select Committee heard evidence of a social security system that is built upon fear and intimidation. The Committee heard how sanctions can devastate claimant health and wellbeing. They impoverish already poor people and drive them to food banks. They can leave claimants even further away from work. Jobcentres routinely harass vulnerable jobseekers, “tripping them up” so they can stop their benefits and hit management-imposed sanctions targets (or as the Department for Work and Pensions would have it, “expectations” or “norms”).

Conservative claims about welfare sanctions are incommensurable with reality, evidence, academic frameworks and commonly accepted wisdom. It’s inconceivable that this government have failed to comprehend that imposing punishment in the form of financial sanctions on people who already have very limited resources for meeting their basic survival needs is not only irrational, it is absurdly and spectacularly cruel.

Sanctions are callous, dysfunctional and regressive, founded entirely on traditional Conservative prejudices about poor people and ideological assumptions. It is absolutely unacceptable that a government treats some people, including some of the UK’s most vulnerable citizens, in such horrifically cruel and dismissive way, in what was once a civilised first-world liberal democracy.