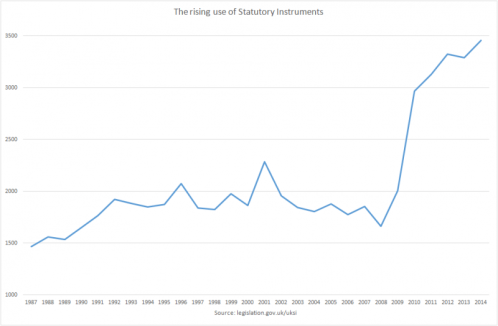

The government’s behavioural change agenda, which targets the poorest citizens, is being delivered via the increasing conditionality of social security and public service support provision. The underpinning rhetoric is that individual behaviours cause poverty, rather than government policies, which are causing a systemic unequal distribution of wealth.

Councils who are facing shortfalls in government funding to meet their statutory obligations have recently introduced behavioural conditionality to applications for awards of Discretionary Housing Payments (DHP). Most local authorities are now saying they will only help those who will have a “positive outcome” as a result of the support. Yet they claim that this is to ensure limited funds go to only those “most in need”.

The reasoning provided by councils for only supporting those “nearest to the labour market” to encourage “financial independence” is at odds with the aim of ensuring support goes to “those most in need”. Surely those unable to work through illness and disability, who are furthest away from the labour market, actually have more need, yet will be less likely to meet conditionaility requirements and so won’t receive the support that the government tells us is supposed to be in place for us.

DHP is now much less likely to be awarded for those in greatest need precisely because of the new conditionality criteria. It specifically supports people who are more able to find work. Those who can’t are expected to go without food and fuel to meet their housing costs and potentially face destitution.

Disabled people paying for disabled people’s support

On Thursday I went to apply for DHP as I no longer have enough money to live on, partly because of now having to pay council tax and bedroom tax. Like many people, my essential outgoings are considerably greater than my income. The government have claimed that disabled people like me can claim DHP as a safeguard from the financially damaging impact of the bedroom tax, which disproportionately affects disabled people.

However, my own council have warned me in advance that they have little funding left for providing DHP support.

ESA and other benefits were originally calculated to meet the costs of food and fuel, and other essential living costs, based on an assumption that you would also get FULL housing and council tax benefit. There hasn’t been full housing benefit provision for some years now, but previously, people who are disabled were exempt from paying council tax, until recent years.

This is leaving some people without enough money to meet the costs of their basic survival needs – food, shelter and fuel. One reason I now have to pay more council tax, according to the statement from my local authority on my bill, is to raise money to meet the costs for the government’s pledged funds for improving adult social care – the adult social care precept. That is being taken from every household, including the poorest, many of which have people with serious medical conditions and disabilities in them.

My local authority says: “The introduction of the National Living Wage and increase in population means this is an area where we have seen significant financial pressures. The 2% increase will help us to maintain our current services.”

There’s a certain horrible irony here, too.

My local authority inform me that I now have to pay council tax to fund support for:

- older people

- people with a learning disability

- people with a physical disability

- people with sensory loss

- people with mental health needs

The never-ending need to justify need: facing the bureaucratic wall around support provision

I am a person with physical disabilities because of an illness, and my only income is my ESA, at the support group rate. I ought to have claimed Personal Independence Payment (PIP) before now. However my experiences claiming ESA were extremely distressing and anxiety provoking, and that has deterred me. The enormous stress and anxiety of the assessments, facing a tribunal and then the reassessment almost immediately after I won my case in court exacerbated my already serious illness, and left me acutely and desperately ill for at least two years.

I’m a reasonably robust person ordinarily. I have worked most of my life, and I enjoyed my work, particularly the youth and community posts I undertook. I did a vocational part-time Master’s while I worked full time, and later went on to do mental health social work with young people at risk.

I was very unprepared for what followed when I suddenly became very ill with lupus. I was used to being fit, healthy and very active. I also had a good salary and a relatively comfortable standard of living. Though I was never very affluent, I had enough to cover my family’s needs, and to provide enough for my children to have stability.

I was forced to give up work as I was much too ill to fulfil my role competently and there were significant risks to my health in the workplace. My illness and some of the treatments I have also mean that I am very susceptible to infection. I caught a cold from a colleague in work and ended up with pneumonia and pleurisy more than once, for example. My illness impacted on my capacity to work for many reasons, such as an autoimmune bleeding disorder, widespread joint and tendon damage affecting my mobility, severe nerve pain, deteriorating eyesight, neurological problems, cognitive and coordination difficulties and so on. The tribunal panel (regarding my ESA eligibility) concluded that I had made the right decision to leave work because of the further serious risks to my health, after reading my medical reports from specialists.

My house was repossessed because my modest mortgage payments became unmanageable as I had no way of making the payments. I did approach my local housing office for help, who told me they could only offer support once I was actually homeless. That would have meant having all my family’s possessions left on the street, too.

I found a house to rent just down the street for a very reasonable amount. In fact initially there was very little shortfall between my housing benefit and actual rent. I had two sons still at school, they didn’t want to leave the area as they were in their final years, and we have other family in this area. I was informed by the council that I would be eligible for housing benefit for a three bedroom house at that time. I took out a small loan for my deposit, as by then my last wage had long gone. The council were pleased I had managed to find cheap accommodation that suited my family’s needs.

I moved into the property, but I was very ill and struggled coping. My disability advisor at the job centre advised me to claim ESA at this time. By then I was having weekly chemotherapy treatment (Methotrexate) at the hospital and was considered unavailable for work, I didn’t (and couldn’t) meet the jobseeker’s allowance conditionality requirements, and my advisor recognised this.

Within two months of moving into the property, the law changed, and I had to pay bedroom tax for my older son’s room, as he was suddenly expected to share a room with his younger brother. There are no smaller houses locally, none with lower rents, and all of the limited number of two bedroom council flats here are inhabited. Not that moving again would have been easy for me as I was so poorly at this time. The first move down the street had affected my health, and exhausted me for months.

However, after almost a year of struggling to pay the bedroom tax, my oldest son reached 18 and my housing benefit went back up not long before he left for university. I got almost a year of backpay when I won my ESA tribunal and that helped me get on top of my increasing debt, after months of really struggling. I also got a tax rebate from when I worked, also helped enormously.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) decided that they would take back an overpayment they made in 2007, while I was struggling on basic rate ESA, awaiting tribunal in 2011. I was also paying bedroom tax then. I had claimed income support briefly when I changed jobs, whilst I waited for social services to complete background checks that were necessary for my post. I couldn’t start the post until the checks were done. Meanwhile we had nothing to live on. The checks took three months.

I was entitled to a month of run-on benefit as a lone parent once I took up the post. However, despite the fact I had signed off, the income support payments continued another two months. I had phoned a couple of times and then written twice to inform the job centre again that I had taken up my post.

I don’t mind paying back the money I was overpaid. I did mind that the DWP also took back the run-on benefit that I was actually entitled to for the first month, and told me it was far too late to appeal that decision. The hefty deductions from my reduced ESA did cause me a lot of hardship, but at least I didn’t owe anything by the time I won the tribunal. It was claimed I did still owe money at one point and I had a letter saying my ESA back dated payment wasn’t going to be released as I owed money. I didn’t.

It’s almost as if the DWP want to keep people in a state of constant anxiety, despair and precarity, and to make sure that your life is never remotely acceptably comfortable, secure and safe. Social security is no longer a safety net, it seems to have been transformed into a bureaucratic wall that exists simply to discipline poor people and ensure as few people as possible have access to any lifeline support. The letters are written in a way that intends to cause anxiety, I am sure.

I managed financially for a couple of years, though budgeting on such a limited income is difficult. But having worked for a long time, I had furniture and household items, enough clothing and when things got very bad, I had a few personal items to sell if need be.

Of course over time, vacuum cleaners, washing machines, fridges, kettles and cookers break down. Children grow and need clothes and shoes. I went a whole year without a washing machine when mine broke, but saved a little every month until I had enough for a second hand one. I don’t know how I managed to get by because much of the time I could barely walk or use my wrists/hands, but I had to wash clothes and bedding in the bath. It took up a lot of my time and effort. Poverty is cumulative, too. It gets much worse and more wearying as time goes by. If you are ill and disabled, the impacts of poverty are considerably greater.

Both my youngest sons are at university now. They come home out of term times. I feed them and support them as best I can, though we don’t have any money to cover their living costs. Both are at universities out of the region, they have student finance for term times, but both have struggled to meet living costs. When they come home, it’s for a couple of weeks, though considerably longer at Christmas. They have never managed to find work locally to tide them over out of term time, despite trying. No-one wants to hire people for a couple of weeks.

My oldest son found a part time job in his first year at university. He didn’t have regular hours and his employer simply called him when he needed him. However, my son’s travel costs to and from work exceeded what he earned, and more than once his allocated hours coincided with his lectures, which are compulsory.

Both boys are considered as living at home as they return home out of term times and are expected to return home once they complete their studies.

In the new year, I caught ‘flu and within a couple of days I ended up with pneumonia and sepsis. At the time I was far too ill to know I was so poorly. It was my son who realised how serious my condition was and rang the ambulance, just in time.

I was already in a critical condition with septic shock when the ambulance arrived. My illness means my immunity to infection is very low, so I’m always at risk from pneumonia, kidney infections, random abscesses and so on, but this was the first time I have ever had life-threatening and severe sepsis. I was very ill in hospital and spent a couple of days drifting in and out of a bottomless sleep and hallucinating, while on the lifesaving IV treatments and fluids. I needed oxygen support for five days afterwards, anticoagulant injections, and continued taking combined oral antibiotics, steroids and a course of Tamiflu for a couple of weeks after I came home.

When I got home from hospital in late January, we had no hot water or heating as my boiler had broken. But we used fan heaters, and I managed to keep warm in my room, I focused on recovery, until the electric went off because of a fault on a circuit. My landlord lives in the US currently and I had difficulty in contacting him. I had no choice but to find somewhere else to stay as the house was so cold it was uninhabitable, and we couldn’t cook food. I was still very weak and very slowly recovering. By this time my youngest son had returned to university. My oldest son and I had to stay with a friend.

The electrical fault was fixed and I got a new boiler fitted the following week. I remained weak and my pulmonary specialist told me it would likely be at least three months before I was fully recovered. I have been diagnosed with additional lung problems since, which showed up on a scan, following more tests showing my lung function is just 40% of what it is expected to be. Some of the problems are related to lupus, which has caused a lot of inflammation in both lungs.

My son decided I needed some additional support to recover and he has taken six months out from his degree to care for me. The alternative was for me to contact social services for support.

I now have to pay bedroom tax for his room, in addition to the council tax, as he is classed as a non-dependent adult. Having no boiler for several months has also meant I used a lot more electricity, so my bill is much bigger than usual, so my direct debit has more than doubled every fortnight. I managed to negotiate it down a bit, but it is still more than twice my usual payment. My new boiler is a lot more efficient than the old one, luckily, but I am nonetheless struggling to make ends meet.

So I applied for DHP.

I had an interview on Thursday at our local housing benefit office.

Rent and council tax are more important than food and fuel, apparently

The interview went as follows:

Firstly, I was asked to give an account of my income and outgoings.

Housing Officer: What have you done to look for work?

Me: I am in the Employment Support and Allowance Support Group (ESA). This is because I became too ill to work and it’s been agreed by my doctors, myself and the state that I can’t work “consistently, reliably and safely” due to the severity of my illness and the substantial risks I would face if I were to return to the workplace. I have tried to find a job writing from home that pays a wage to support myself, but had no luck so far.

Housing Officer: What have you done to look for cheaper accommodation?

Me: I wasn’t aware I was expected to. However, there is no cheaper accommodation in the area, unless you have any two bedroom social housing to offer me. Then I would need considerable support in moving, as my illness means I have mobility problems, severe problems with profound fatigue, other health problems that make moving risky, and I also need to be organised to accommodate a strict routine for my health care.

Housing Officer: Have you considered taking in a lodger?

Me: I have no spare room to offer a lodger as my sons occupy them out of term time and are expected to return home once they graduate. However, I would not consider taking a stranger into my home because I am disabled and ill, therefore I am potentially vulnerable and feel that this may present an unacceptable risk to my wellbeing and safety. (See for example: Mother and son who ‘gave shelter to homeless man’ stabbed to death at family home.)

Housing Officer: Your weekly shopping average looks slightly high.

Me: Well at the moment it is for two of us. On Friday my youngest son is home for the Easter break, and I will then need to feed him too.

Housing Officer: I only want details of what you spend on yourself.

Me: Do the council expect that I leave my children without food?

(No response)

Me: My weekly shop includes essential items I can no longer get on prescription, such as eye drops, because my tear film is very poor, I don’t produce tears as I have Sjogren’s – painfully dry eyes – as part of my illness. I used to get moisturising drops on prescription from my opthalmologist but they have been discontinued. If I don’t use the eyedrops my cornea becomes scarred and I get eye infections.

I also have to buy sunblock, because I get a blistering and painful rash in the sunlight, even in winter – that’s also part of my illness.

I have to buy detergents and toiletries that are very hypoallergenic and gentle because my skin is fragile, hypersensitive, prone to rashes and painful blistering in places because I have lupus and eczema, all of which leaves me prone to infection if I don’t treat the conditions with care. I also have to buy cleaning products and antibacterial items, to keep my home as clean as possible because my illness and treatments mean my immunity to infection is very poor.

None of these items are available on prescription, but I do unfortunately need them. I have also included very modest clothing/footwear costs (I have to take care with footwear because I have severe Raynaud’s – a condition that causes very poor circulation that shuts down in my hands, feet and nose with even slight fluctuations in temperature – and so I need to keep my feet and hands warm. I am prone to blisters from badly fitted shoes which then turn into serious infections and have developed sepsis at least once because of this. I also need shoes that are cushioned and support my Achilles tendons because of damage to them and my joints.

I’ve also included modest costs for essential household items, which everybody needs sometimes due to wear and tear. I have a bleeding disorder, which affects me in a way that means I have to spend more on sanitary items than most people. I also have additional dietary needs because I am underweight, and I have IBS and acid reflux, which means I have to eat small meals frequently throughout the day. This is not a lifestyle choice: it’s because of my medical conditions.

Housing Officer: Don’t take any of the questions personally, everyone is asked the same.

Me: The problem with having the expectation of everyone having the same needs is that you then don’t have any opportunity to recognise the more vulnerable clients who need additional support because of their additional needs. Not everyone finds it easy to find suitable employment to support themselves. Illness and disability can happen to anyone, it is sometimes a major barrier to working and I am not ill because of “lifestyle choices”: it’s not because of something I did or didn’t do. I have worked. Now I can’t.

People are dying because of that built-in oversight and other government policies that don’t accommodate people’s circumstances and disregard their additional needs because of disability and illness. Many others are suffering unacceptable distress and harm to their health.

Housing Officer: I know.

She delivered that comment with complete and almost menacing detachment. I was so taken aback I couldn’t speak for a few moments. She didn’t even pause for breath, however.

The part that was by far the worst during the interview was this matter-of-fact agreement that people are dying as a result of the policies that she was calmly sat implementing.

It was delivered almost like a veiled threat: that if I didn’t or couldn’t comply with certain unstated behavioural requirements, which were not made explicit at any point during the interview or prior to it, I would also be left to die.

I was then told I must “prioritise” my rent and council tax payments above everything else.

I explained that my rheumatology consultant has also told me I must prioritise eating well, putting weight on (I weighed less than 8 stones), and keeping warm (I have severe lupus-related Raynaud’s disease that leaves me very susceptible to severe infections and gangrene in winter.) I don’t have enough income to do both of those things, as it is. I explained again that I could meet my housing costs before I had to pay council and bedroom tax, and have managed to do so until now, and this is why I had applied for DHP.

My comment was met with silence.

Apparently, not falling into rent and council tax arrears is more considered more important than meeting basic survival needs such as eating and keeping warm.

I was also almost casually asked if I had any pets or Sky TV. Next I was asked if I had a TV, broadband and a mobile phone contract. I was asked how much I spend on my phone monthly (it’s a pay as you go). I felt I was being turned into a Daily Mail stereotype by bureaucratic questioning that was designed to find ways of dismissing me as ineligible for support in an arbitrary way, under the cover of mundane chit chat.

The more I responded the more demand was placed on me to justify my outgoings, the more information I presented, the bigger the scope for potentially finding reasons for refusing my application.

ESA and PIP assessments work in much the same way – assessors fish for as much information as possible about your everyday life so they can use it to try and claim you are more able to work and less disabled than you and your doctor are claiming.

For example, “Do you watch soaps on TV?” – a deceptively conversational and informal question – may translate your response on the report potentially, as “Can sit unaided and concentrate for at least half an hour”. The aims and motives behind the questions are deliberately obscured, so that you don’t have an opportunity to explain or clarify any details or challenge the assumptions being made to justify ending your lifeline support.

That gold locket and chain that was your mother’s, which you wear all the time because you can’t take it off, as the clasp is too difficult for your arthritic fingers, becomes a sign of finger and hand dexterity to an assessor, as it’s just assumed you take it off and put it on again. When I had a chest x-ray recently, I had to ask the radiographer to take it off. The whole process is designed to search out ways to discredit your doctor’s and your own account by any means at all concerning the level of your disability and the impact it has on your day to day living and work capability.

Agents of state control and “changing behaviours”

Behavioural conditionality has now been built into every aspect of social safety net provision, this is to save costs and ultimately, to justify the dismantling of social security, public services and healthcare provision. It is justified by an ideological narrative of the neoliberal “small state”, austerity and paying off the national deficit, the “unsustainability” of safety net provision and the state re-translation of competitive individualism into a rhetoric of self help, thrift and “personal responsibility”. Only for the poorest, of course. Thrift and self help doesn’t apply to government ministers, whose lavish lifestyles, food and fuel, housing costs, and so on are funded by the tax paying public.

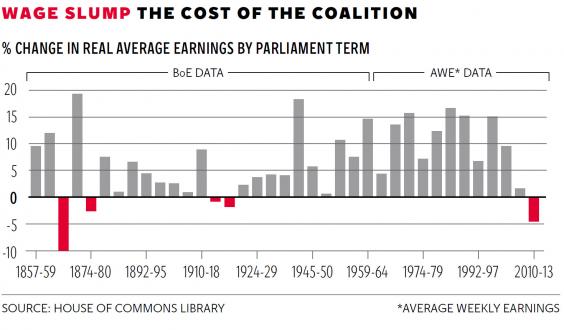

The behavioural change programme is being applied only to poor and vulnerable citizens. Against a backdrop of austerity and welfare “reforms” (cuts), millionaires were awarded a tax cut of £107,000 each per year, exempting them from the same obligation to practice personal responsibility, thrift and self help. The Conservatives’ low tax and low welfare society means that perversely, those who have a lot of money are not expected to contribute to our society, whereas those who are low earners or unemployed are expected to pay down the deficit and pull themselves up by imaginary bootstraps.

If you suffer or die in the process, apparently that is okay because the government inform us there is no “causal link” between such “adverse” consequences and their adverse policies. However, a correlation has been well-established by independent research and the narratives of many of those affected by the draconian policies, as well as campaigners.

What really struck me during my housing benefit interview was how the ordinary and seemingly reasonable woman in front of me seemed to suddenly shapeshift into a resentful, disapproving and prejudiced state drone who didn’t feel I deserved any support, about a third of the way into our interview. I felt like Iain Duncan Smith was conducting the interview.

The government have built up almost impenetrable walls of authoritarian bureaucracy around social security provision, and a hive mind army to deliver their distinctive and punitive approach to poverty, which is now all pervasive. All bullies seek the “behavioural change” of others to get their own way. Conditionality is built upon a behavioural change agenda to prop up neoliberal policies aimed at removing social provisions that the poorest citizens need to survive. Work is no longer the panacea it is held to be, since labour market deregulation and intentionally low social security creates a reserve army of labour, which “incentivises” profiteering employers to keep wages low.

Even a trip to your GP is likely to trigger the question “do you work” these days, as job coaches are co-located in surgeries to enforce the government’s “work cure” and suck you back into a supply side reserve army of desperate labour. However, sometimes people are simply too ill to work. The state and its wall of bureaucracy, however, are absolutely refusing to accept this.

There is no end to intrusive state nudging and shoving, especially when you just want to be left to cope with being progressively ill in peace. The government believe that illness and disability are simply a set of “faulty” behaviours that need correcting, and that people will respond to a particularly punitive form of operant conditioning in order to change their behaviours to bring about a miraculous recovery. Work is considered a “health” outcome. However, work is a work outcome and has nothing whatsoever to do with a person’s health. In my own experience, work considerably contributed to the progression of my illness. Being constantly expected to work has also contributed significantly to the deterioration in my health.

Furthermore, I don’t recall giving consent for my taxes and national insurance to be used to pay rogue companies that cost the public billions to “save” relatively meagre amounts in welfare and public service spending just to punish, bully and coerce people who need support.

Nor did I give consent to a state experiment in value-laden, ideological, poorly designed and prejudice-determined operant conditioning on ill, disabled and unemployed citizens.

Cameron was surely mocking when he used this phrase as a slogan from Terry Gilliam’s darkly dystopic film, “Brazil”, which was coincidently about nightmarish totalitarian bureaucracy

There were no innocent and random comments from the interviewing housing officer. Almost every question was geared towards making me feel guilty for being poor and not being in work, I was challenged over every single penny I spent, as if I have no right to food, items that I need to meet my complex health needs, and no right to extend an ordinary gesture of basic kindness and decency by taking in a stray cat that had no home and no-one. I’m surprised I wasn’t asked to sell everything I had bought and kept from when I worked.

I had no idea that disabled people could be refused support if they had a pet. Regardless of whether that pet was one you had when you were in better circumstances, working. How utterly callous to expect people to dispose of their cherished companions when they experience hard times, it’s cruel on the person and cruel on the poor and innocent animal.

Most pets cost very little to feed, too.

My cat is a great source of calm and comfort for me, at a time when I am struggling trying to constantly adapt to a progressive illness, and increasing absolute poverty. I couldn’t bear to part with her.

I wonder what the decision-makers, who are gatekeeping funds that I have contributed to – and they are meant to support disabled people rather than punish them – expect a person should actually do with a cherished family pet, which may have been a part of a family long before severe financial problems and illness came along.

It’s rather like financially penalising people by cutting off support for some children just because a parent has lost a job and encountered difficult times. It’s a Poor Law/Work House mentality – we are all categorised as either “deserving” or “undeserving” based on our previous choices as well as our current ones. How very dare anyone have anything at all that gives them a little joy and comfort if they become too ill to work. Even if they worked for it prior to losing their job or becoming ill.

This said, those people who have never been able to work should be supported, unconditionally and without any resentment, to meet their living needs and to lead safe and secure lives. This is how a democratic, decent and civilised society should behave, after all.

I don’t need a behavioural change agenda. My behaviour didn’t put me in a position of hardship: ill-conceived state policies that disproportionately target ill and disabled people for austerity cuts are the root cause of my financial problems. I am not ill because of my behaviour, my medical condition arose because of a complex interplay between genetics (my mother and her father had a autoimmune/ connective tissue disease, and both my maternal aunt and uncle do), hormonal events (pregnancy was probably the trigger in my case, as that is when I first became ill, 21 years ago) and possibly some environmental triggers too, such as an infection. It was not because I did or didn’t do something. No-one could have predicted a pregnancy would trigger a autoimmune/connective tissue disease. No-one knows how it will progress either, unfortunately. I managed to work for some years whilst being ill, and stopped only because I absolutely had too when I my symptoms became too severe.

Neoliberalism is founded on the principles of “market competition” and competitive individualism. In competition, a few people do very well and “win”, and many more don’t. That is the nature of competition. This is how it works.

Neoliberalism itself causes inequality and poverty, whilst rewarding most the people who are already very wealthy. Addressing the “behaviours” of poor people to punish them into not being poor won’t change the consequences of inequality because of our socioeconomic organisation one bit. Poverty, by it’s very nature, reduces behavioural choices and opportunity.

It’s really the government who need to change their policies and prejudiced behaviours, not poor, ill and disabled people.