You can often tell such a lot about people’s views and sometimes, their intentions, by the words and phrases they use. The description of disabled people as being “parked” on benefits (and “told/under the impression they will never work again”) is a turn of phrase I loathe. It’s a mantra that’s gained a PR crib sheet resonance from George Osborne and Iain Duncan Smith to Stephen Crabb and Damian Green. To extend the metaphor, parking is subject to the availability of a parking space; permission; to regulations and laws; parking tickets and fines; parking attendants and traffic wardens to police and ensure compliance.

Disability and sickness are compared with the inconvenient abandonment of a vehicle in the middle of a very busy market place. Or the informal blatant plonking and installing of oneself on a sofa or bed, behind outrageously closed curtains in the middle of a busy viral epidemic of the protestant work ethic, prompting further symptoms of oppressive impacted resentments and frank, febrile tutting.

Yet the Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) Support Group is made up of those individuals who “have a severe limitation which creates a significant disability in relation to the labour market, regardless of any adaptation they may make or support with which they may be provided” (Department for Work and Pensions, 2009: 8).

Disabled people are being excluded, and at the same time, represented in political and mainstream discourse in ways to evoke moral judgments and public emotions such as distrust, disgust and anger. Evidence of state culpability lies in the relationships between political rhetoric, media narrative and punitive, populist social policy.

However, in official policy documents, welfare cuts have been dressed up as a discourse related to “support” , “social inclusion” and even “fairness” and “equal opportunity”. Though this is only narrowly discussed in terms of employment outcomes. “Inclusion” has been conflated with being economically productive. In contrast, the media rhetoric, and importantly, the consequences of Conservative policies aimed at disabled people, are increasingly isolating and exclusionary, as a result of intentional political outgrouping.

Yet such rhetoric is surely also counter‐productive to even such a limited view of inclusion, inevitably distorting employer responses to ill and disabled people as potential employees. However, Conservative neoliberal policies reflect a consideration of the supply rather than the demand side of the labour market.

“[…] rather than being concerned with the economic position of disabled people in Britain, the development of the Employment and Support Allowance and the Work Programme was concerned with relationships between the supply of labour and wage inflation, and with developing new welfare (quasi) markets in employment services. Attempting to address the economic disadvantages disabled people face through what are essentially market mechanisms will entrench, rather than address, those disadvantages.” From: Commodification, disabled people, and wage work in Britain – Chris Grover.

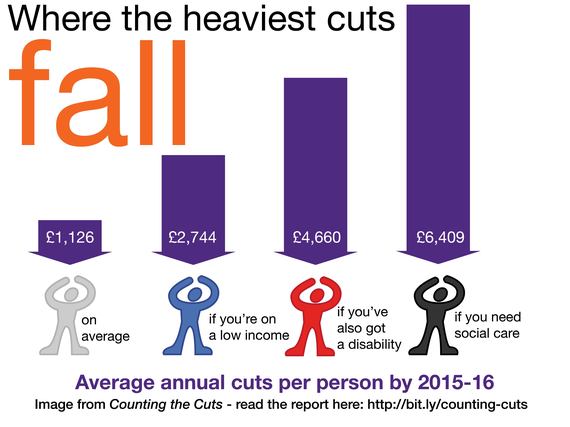

Glib, deceptive and diversionary language use and ideological referencing does nothing to address the social exclusion of disabled people, who are already pushed to the fringes of society. Disabled people have become easy political scapegoats in the age of austerity. Scapegoating and outgrouping have become common political and cultural practices. Stigma is being used to justify the most regressive social policies since before the foundation of the welfare state in the 1940s.

Patronising and authoritarian Conservatives like to speak very loudly over disabled people, and tell us about our own experiences because they really believe we can’t speak for ourselves. They simply refuse to listen to people who may criticise their policies, raising the often dire consequences being imposed on us because of the “reforms” CUTS. I also think that we are witnessing the most powerful anti-intellectual and anti-rational ethos in government in living memory.

Whilst Conservative rhetoric lacks coherence, rationality, integrity and verisimilitude, it has an abundance of glittering generalities and crib sheet repetition designed from supremacist decisions made around elitist tables behind closed and heavy doors. The Conservatives seem to believe that disabled people aren’t like other citizens and that we don’t need a democratic voice of our own. Policies are designed to act upon us, to “change” our behaviours through the use of “incentives”, whilst we are completely excluded from their design and aims. Our behaviours are being aligned with neoliberal outcomes, conflating our needs and interests with the private financial profit of others.

As one of the instigators and a witness for the United Nations investigation into the government’s systematic violations of the human rights of disabled people, as a person with disability, I don’t care for being described by a blatantly oppressive Damian Green as “patronising” or being told that disabled people – witnesses – presented an “outdated view” of disability in the UK. The only opportunity disabled people have been presented with to effectively express our fears, experiences, concerns about increasingly punitive and discriminatory policies and have our democratic opinion heard more generally has been through dialogue with an international human rights organisation, and still this government refuse to hear what we have to say.

Oppression always involves the objectification of those being dominated; all forms of oppression imply the devaluation of the subjectivity and experiences of the oppressed.

Just as Herbert Spencer supported laissez-faire capitalism and social Darwinism (on the basis of his Lamarckian beliefs) – and claimed that struggle for survival spurred self-improvement which could be inherited – the Conservatives apply the same tired and misguided, private boarding school myths and disciplinarian moral principles in their endorsement of a totalising neoliberalism: the bizarre belief that competition, struggle and strife is “good” for character and even better for the market economy.

Under the Equality Act 2010 there are several types of discrimination that are prohibited. These are direct discrimination (s.13(1) Equality Act 2010), indirect discrimination (s.6 and s.19 Equality Act 2010, harassment (s.26 Equality Act 2010), victimisation (s.27(2) Equality Act 2010), discrimination arising from disability (s.15(1) Equality Act 2010) and failure to make reasonable adjustments (s.20 Equality Act 2010).

Disabled people are being conveniently reclassified to fit Treasury cost-cutting imperatives. However, the government prefer to say that we are claiming lifeline support because we are “disincentivised” to find a job because we are claiming lifeline support… there’s a whole ludicrous circular government monologue going on there that we are being quite intentionally excluded from.

This is one common type of ableist behaviour: it is a form of discrimination which denies others’ autonomy by speaking for or about them rather than allowing them to speak for themselves. Ableism characterizes persons as defined by their disabilities and as inferior to non-disabled persons. On this basis, people are assigned or denied certain perceived abilities, skills, and/or character traits. And often, denied rights and a democratic voice.

If you ask disabled people about work, most of us will say we would like to – after all, who of us would actually choose to be ill and disabled – but there are social, political, cultural and economic barriers to our doing so. None of us will tell you we don’t work because we feel secure and comfortably off on an ever-dwindling and paltry amount of ESA, which has been subjected to cuts, further threats of cuts from prominent think tanks, increased conditionality, the threat of sanctions, and constant, distressing assessments and reassessments which were designed to find ways of stopping your lifeline support.

Disabled people became amongst the first citizens of a new class: the precariat. In sociology and economics, the precariat is a social class formed by people suffering from precarity, which is a condition of existence without predictability or security, affecting material and psychological welfare. The emergence of this class has been ascribed to the entrenchment of neoliberalism.

Many disabled people, however, will tell you that they are simply too ill to work. It’s a ludicrous and frankly terrifying state of affairs that the administrating despots in office don’t accept that some people simply cannot work, and persist in hounding them, claiming that cutting social security, originally calculated to meet only basic needs and now reduced to the point where that is no longer possible, is somehow an “incentive” for very sick people to find work. It’s incredible that the government are telling us with a straight face that a poor person’s “incentive” is punishment and financial loss, whilst millionaires are “incentivised” by reward and financial gifts, such as “tax breaks”.

The same approach is apparent in the recent green paper on work, health and disability, where the government casually discusses subjecting disabled people in the ESA support group to compulsory work related activity and “behavioural conditionality” (sanctions are suggested), though the support group were previously exempt from the punitive welfare conditionality regime, since their doctors and the state accepted that this group of people are simply too ill to work. Employers, it is suggested, are to be “incentivised” by financial rewards – tax cuts. When this government discuss “being fair” to the “tax payer”, they are referring to wealthy and privileged people, not the majority of ordinary citizens such as you and I.

Discrimination is defined as “treating a person or particular group of people differently, especially in a worse way from the way in which you treat other people”, based on characteristics or perceived characteristics. Under Labour’s 2010 Equality Act, direct disability discrimination occurs when a disabled person is treated less favourably than a non-disabled person, and they are treated this way for a reason arising from their disability. Indirect discrimination happens when an organisation or government has a particular policy or way of working that has a worse impact on people who share your disability compared to people who don’t. Harassment is defined as someone treating you in a way that makes you feel humiliated, offended or degraded.

The government even have the cheek to call their discrimination “supporting” and “helping” us. I’ve never heard of such immorality, bullying, indecency, prejudice and punishment being called “help” and “support” before. Millionaires are helped; they get financial handouts in the form of tax cuts that they don’t need. Meanwhile we have lifeline income taken away to fund, leaving us without food, fuel and shelter increasingly often. Such mundane language use is an attempt to mask the intentions and consequences of draconian policies. It utterly nasty, manipulative, callous, calculated cold-blooded gaslighting.

Milton Friedman, in Capitalism and Freedom (1962) felt that “competitive capitalism” is especially important to minority groups, since “impersonal market forces”, he claimed, protect people from discrimination in their economic activities for reasons unrelated to their productivity. Through elimination of centralized control of economic activities, economic power is separated from political power, and the one can serve as counterbalance to the other. However, he couldn’t have been more wrong. What we have seen instead is an authoritarian turn. The UN conclusions to their recent inquiry into the government’s systematic and grave violations of the rights of disabled people verify his lack of foresight and his conflation of public needs and interests with supply-side economic outcomes.

A word about the use of the term “vulnerability”

The reason that some groups are socially and legally protected – and the reason why we have universal human rights – is because some groups of citizens have historically been vulnerable to political abuse and are structurally discriminated against. The aim of human rights instruments is the protection of those vulnerable to violations of their fundamental human rights. The recent United Nations inquiry into the UK government’s systematic violations of the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities concludes that disabled people in the UK are facing systematic political discrimination, social exclusion and oppression.

The Yogyakarta Principles, one of the international human rights instruments use the term “vulnerability” as such potential to abuse and/or social exclusion. Social vulnerability is created through the interaction of social forces and multiple “stressors”, and resolved through social (as opposed to individual) means. Social vulnerability is the product of social inequalities. It arises through social, political and economical processes.

Whilst some individuals within a socially vulnerable context may break free from the hierarchical order, social vulnerability itself persists because of structural – social, economical and political – influences that continue to reinforce vulnerability.

The medical model is a perspective of disability as a problem of the person, directly caused by disease, trauma, or other health conditions which therefore requires sustained medical care in the form of individual treatment by professionals. The medical model sees management of the disability as central and ideally, it is aimed at a “cure,” or the individual’s adjustment and behavioural change that would lead to better “management” of symptoms.

The social model of disability outlines “disability” as a socially created problem and a matter of the full inclusion and integration of individuals into society. In this model, disability is not an attribute of an individual, but rather a complex collection of conditions, created by the social environment. The management of the problem requires social and political action and it is the collective responsibility of society to create an environment and context in which limitations for people with disabilities are minimal. Equal access and inclusion for someone with an impairment/disability is a human rights concern.

From the 70s, sociologists such Eliot Friedson observed that labeling theory and a social deviance perspective could be applied to disability studies. Social constructivist theorists discussed a non-essentialist perspective: the social construction of disability is the idea that disability is constructed as the social response to a deviance from the norm. “Disability” is constructed by social expectations and institutions rather than biological differences.

I think there is something positive to learn from the variety of models of disability, and should like to point out that despite the potential merits of any one in particular, each have also been heavily criticised, and most importantly, there is nothing to stop an unscrupulous government from intentionally exploiting a theoretical paradigm to suit an ideological design.

Eugenics

The French statistician, Alphonse Quetelet wrote in the 1830s of l’homme moyen – the “average man”. Quetelet proposed that one could take the sum of all people’s attributes in a given population (such as their height or weight) and find their average, and that this figure should serve as a norm toward which all should aspire. This idea of a statistical norm threads through the rapid growth in the popularity of gathering statistics in Britain, United States, and the Western European states during this period, and it is linked to the rise of eugenics. Disability, as well as other concepts including: “abnormal”, “non-normal”, and “normal” arose from this mindset.

With the rise of eugenics in the latter part of the nineteenth century, such deviations from the norm were viewed as somehow dangerous to the health of entire populations.

As a social and political movement, eugenics reached its greatest popularity in the early decades of the 20th century, when it was practiced around the world and promoted by governments, institutions, and influential individuals. Many countries enacted various eugenic policies, including: genetic screening, birth control, promoting differential birth rates, marriage restrictions, segregation (both racial segregation and sequestering the mentally ill), compulsory sterilization, forced abortions or forced pregnancies, culminating in genocide.

The moral dimensions of the eugenics in the 19th and 20th centuries rejected the doctrine that all human beings are born equal, and redefined human worth purely in terms of genetic “fitness”. More recently in the UK we have seen a moral shift entailing human worth being politically redefined in terms of economic productivity.

Common early 20th century eugenics methods involved identifying and classifying individuals and their families, including the poor, mentally ill, blind, deaf, developmentally disabled, promiscuous women, homosexuals, and racial groups (such as the Roma and Jews in Nazi Germany) as “degenerate” or “unfit”, leading to their segregation or institutionalization, sterilization, euthanasia, and ultimately, their mass murder. The Nazi practice of euthanasia was carried out on hospital patients in the Aktion T4 centres such as Hartheim Castle.

The “scientific” reputation of eugenics declined in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler had praised and incorporated eugenic ideas in Mein Kampf in 1925 and emulated eugenic legislation for the sterilization of “defectives” that had been pioneered in the United States once he took power

After World War II, the practice of “imposing measures intended to prevent births within [a population] group” fell within the definition of the new international crime of genocide, set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union also proclaims “the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at selection of persons.”

Recently the government in the UK introduced policies that curtail tax credits to the children of mothers claiming financial support for more than two children. Iain Duncan Smith announced that the policy was introduced to “change the behaviours” of people claiming welfare. Of course this assumes that people don’t plan and have their children in more prosperous periods of their lives, and then experience financial hardship for reasons that have nothing to do with their behaviours, such as recession and job losses, or being in low paid work and so on.This has some profound implications for notions of equality and the idea that each human life has equal worth. Such a policy discriminates against children because of when they are born, as well as being discriminating against poor families. Such a policy is an example of negative eugenics by “incentives”.

Some campaigners are very critical of the use of the word “vulnerability”, because they feel it leads to attitudes and perceptions of disabled people as passive victims.

Yet I am vulnerable, despite the fact that I am far from passive. Since 2010, no social group has organised, campaigned and protested more than disabled people. Many of us have lived through harrowing times under this government and the last, when our very existence has become so precarious because of targeted and cruel Conservative policies. Yet we have remained strong in our resolve. Despite this, some dear friends and comrades among us have been tragically lost – they have not survived.

In one of the wealthiest democratic nations on earth, no group of people should have to fight for their survival.

I see vulnerability as being rather more about the potential for some social groups being subjected to political abuse.

We are and have been. This is empirically verified by the report and conclusions drawn from the United Nations inquiry into the grave and systematic violations of disabled people’s human rights here in the UK, by a so-called democratic government.

I don’t make any money from my work. But you can contribute by making a donation and help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.