Richard Thaler was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to developing the field of behavioural economics last month. Thaler, and legal theorist, Cass Sunstein, who co-authored Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness (2008), have popularised the ideas of libertarian paternalism, which is basically founded on the idea that it is both possible and legitimate for governments, as well as public and private institutions, to affect and change the behaviours of citizens while also [controversially] “respecting freedom of choice.”

Regular readers will know that I don’t like behavioural economics and its insidious and stealthy creep into many areas of public policy and political rhetoric. The lack of critical debate about the application of libertarian paternalism (which is itself a political doctrine) via policies which are designed as systems of political “incentives” at the very least ought to have generated a sense of disquiet and unease from the public and academics alike.

Using “psychological insights” in public policy – which amount to little more than cheap political techniques of persuasion – no matter how well-meaning the claimed intention is – amounts to a frank state manipulation of the perceptions and behaviours of the public, without their informed consent.

Furthermore, the application of libertarian paternalist policies is prejudiced – it’s asymmetric because the embedded “nudges” are allegedly designed to target “help” at people who are deemed to behave irrationally; those who don’t make “optimal” decisions and so are not advancing their own or wider society’s interests, while the state interferes only minimally with people who are deemed to behave “rationally”.

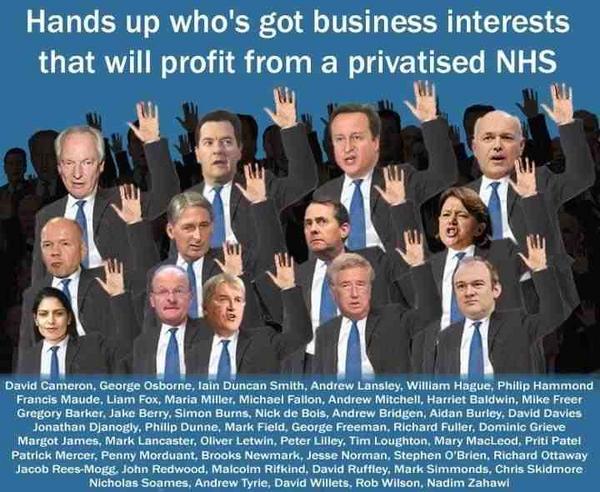

Of course, by some extraordinary coincidence, those who are regarded as behaving rationally are in the minority – they happen to be the very wealthiest citizens. You could easily be forgiven for thinking that behavioural economics is simply a reverberation from within a totalising New Right neoliberal echo chamber. Of course it follows that poverty is the result of the cognitive “deficits” of the poor.

The government would have you believe that poverty has nothing to do with their programme of austerity, their socioeconomic policies, which are generous and indulgent towards the very wealthy, at the expense of the poorest citizens, and the subsequent steeply rising socioeconomic inequality. It’s because of the faulty decision-making of those in poverty.

The political shift back to a behavioural approach to poverty also adds a dimension of cognitive prejudice which serves to reinforce established power relations and perpetuate another layer of prejudice and inequality. It is assumed that those with power and wealth have cognitive competence and know which specific behaviours and decisions are “best” for poor citizens, who are assumed to lack cognitive skills or “bandwidth” (basic cognitive resources).

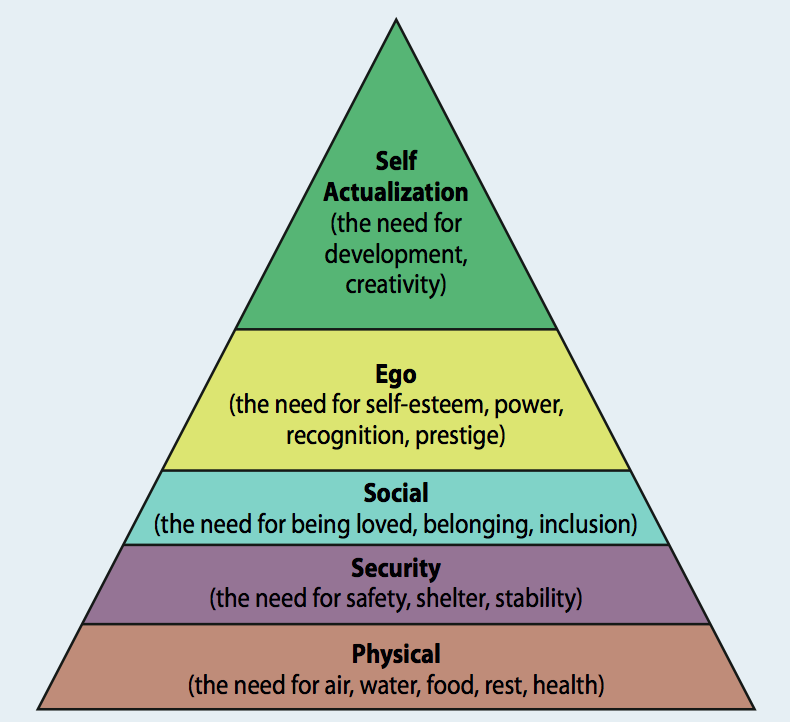

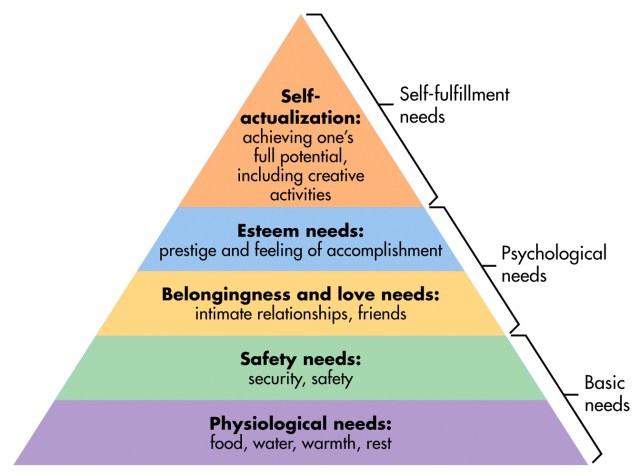

It seems to me that the behavioural economists have colluded with the Conservatives in an ideological re-write of the principles of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs. They say, for example:

“Research shows that money worries can absorb cognitive bandwidth, leaving less cognitive resources to make optimal decisions.”

“Absorb cognitive bandwidth”? What a load of technocratic psychobabbling and politically expedient tosh.

The solution to the problem of people’s widespread “money worries” isn’t nudge – which is simply more ideology to prop up existing ideology. The answer is to increase the income of those struggling with financial difficulties after seven years of austerity, stagnant wages and a rising cost of living. No amount of nudging poor people will redistribute wealth or reverse the effects of bad political decision-making.

Maslow said that hunger, homelessness, being unable to keep warm – problems arising when we don’t have resources to meet our basic physical needs – means that our cognitive priorities are reduced to that of just survival. It means that we can’t fulfil our other “higher level” needs until we address our survival prerequisites. So looking for work and meeting compliance and welfare conditionality commitments by jumping through the endless ordeals that the Department for Work and Pensions put in people’s path to “nudge” them away from social security isn’t going to happen.

I shouldn’t have to say this in 2017, but I will: people have to meet their needs for food, fuel and shelter, or they will simply die. That’s a pretty all-consuming attention grabber. Or struggling to survive absorbs all of a person’s “cognitive bandwidth” if you prefer. It takes up all of your time and effort and becomes your only priority. It’s hardly rocket science, yet the government and their team of behavioural economists seem to be deliberately failing to grasp this fundamental, empirically verified fact. Rather than addressing the socioeconomic and political reasons for poverty, the emphasis is on intrusive state tinkering with the psychological effects of poverty.

Maslow once said that “The good or healthy society would then be defined as one that permitted people’s highest purposes to emerge by ensuring the satisfying of all their basic needs.”

Instead in the UK, the government employs a Nudge Unit to define how and justify why the UK is a shamefully regressive place where many ordinary citizens are hungry, homeless and without the essential necessities to live. That’s because of neoliberal policies that create crass inequalities, by the way, and has nothing to do with people’s “cognitive bandwidth” or their “optimal” decision-making capacities.

Behavioural economics makes the political problem of poverty one of poor people’s decision-making capacity, whereas Maslow saw the problem for what it is – a lack of financial resources to meet basic needs. The answer isn’t to mess about nudging or “incentivising” people, and labelling them as “cognitively incompetent”: it is simply to ensure everyone has enough to eat, has shelter and can keep warm. It’s pretty simple, really, no excuses and no amount of managementspeak and psychobabble may exempt a government from ensuring citizens’ basic survival needs are met. Especially in a very wealthy, developed democracy.

From the government’s perspective, poor people cause poverty. Apparently the theories and “insights” of cognitive bias don’t apply to the theorists applying them to increasingly marginalised social groups. Nor do behavioural economists bother with the “cognitive bias” of the hoarding wealthy, or those whose decisions caused the global crash and Great Recession and the subsequent political decision-making that led to austerity, more aggressive neoliberalism, exploitatively low, stagnating wages and a punitive welfare state that disciplines and punishes citizens, rather than providing for their basic survival needs – which was its original purpose.

No-one is nudging the nudgers.

Conservative policies are extending a behavioural, cognitive and decision-making hierarchy that simply reflects the existing and increasingly steep hierarchy of power and wealth and reinforces competitive individualism and the unequal terms and conditions of neoliberalism. Behavioural economics has simply added another facet to traditional Conservative class-based prejudice, and a prop for the Conservatives’ profound ideological dislike of the welfare state and other public services.

It’s not “science”, it’s ideology paraded as science

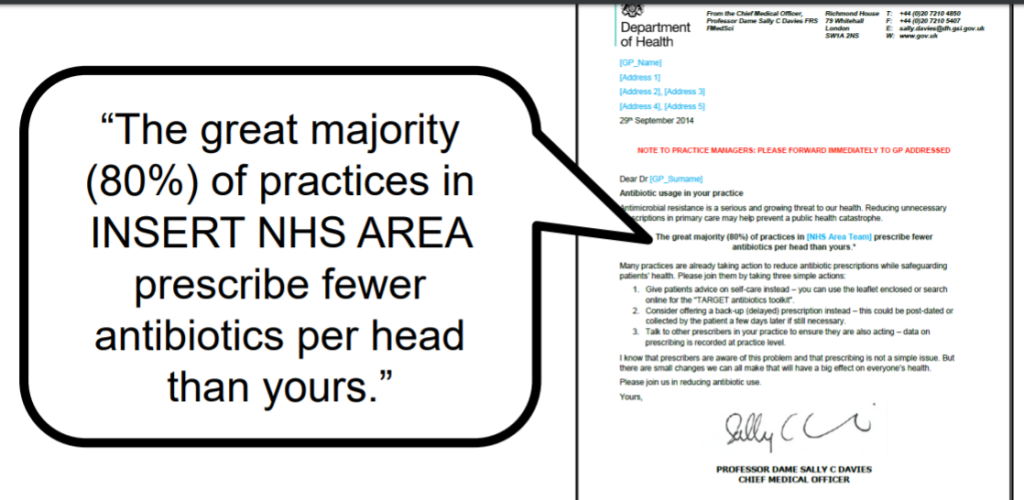

In the UK, the Behavioural Insight Team is testing libertarian paternalist ideas for conducting public policy by running experiments in which many thousands of participants receive various “treatments” at random. There are ethical issues arising from the use of randomised control trials (RCTs) to test public policies on an unsuspecting population. While medical researchers generally observe strict ethical codes of practice, in place to protect subjects, the new behavioural economists are much less transparent in conducting research and testing public policy interventions.

Consent to a therapy or a research protocol must possess three features in order to be valid. It should be voluntarily expressed, it should be the expression of a competent subject, and the subject should be adequately informed.

It’s highly unlikely that people subjected to the extended use and broadened application of welfare sanctions gave their informed consent to participate in experiments designed to test the theory of “loss aversion,” for example. (See The Nudge Unit’s u-turn on benefit sanctions indicates the need for even more lucrative nudge interventions, say nudge theorists.) Furthermore, the experiments are shaped by certain underpinning assumptions. They are not value-free, as claimed.

There is of course nothing in place to prevent a government from deliberately exploiting a theoretical perspective and research framework as a way to test out highly unethical and ideologically driven policies. How appropriate is it to apply a biomedical model of prescribed policy “treatments” to people experiencing politically and structurally generated social problems, such as unemployment, inequality and poverty, for example?

Conversely, how appropriate is it to frame illness and disability purely in terms of individuals’ “faulty” perceptions and behaviours? The de-medicalisation of illness and disability is also a part of the Conservatives’ behaviourist turn, which is part of a justification narrative for the dismantling of support services and social security for ill and disabled people who are unable to work. (I’ve written at length about this here – Rogue company Unum’s profiteering hand in the government’s work, health and disability green paper.)

I guess if the government’s purposeful behavioural modification ordeals fail and you die, then at least the state will know that you were “genuinely” in need of support, after all. This logic operates rather like a medieval inquisitional technique, embedded at the core of the Kafkaesque Work Capability Assessment. The government inform us that this is necessary to aim at sifting out those “most in need” so that the government may “target” support provision to “ensure” that this ever-changing, politically redefined and shrinking group of “those most in need” are somehow distinguished from among the much larger group of those who are, in fact, most in need of support.

The government cannot see the woods because they are so busy indiscriminately pruning and felling the trees.

Most people lacking a strong masochistic tendency would not try to claim disability support unless they desperately needed to. The very tiny minority of fraudulent claimants (less than 0.7%, and some of that tiny percentage includes bureaucratic errors) are unlikely to be deterred by the introduction of ordeals to the social security system, yet this vicious tactic was suggested by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) among others, to “deter fraud.”

However, byzantine “eligibility tests”, an authoritarian monitoring regime to coerce conformity and compliance of social security recipients, and a “robust” shaming and prosecution policy deter “genuine” applicants. Such processes are extremely intrusive, punitive and ultimately serve to reinforce public and political prejudices.

Only those who are truly needy and disadvantaged would tolerate this level of state inflicted, coercive, aggressive and crude behaviourism for the provision of completely inadequate levels of support, through public shaming and through frequent, intrusive administrative forays into their personal lives.

Governments in neoliberal countries portray welfare support as “profligacy” – an “unsustainable” big state over-indulgence – and couple that with a narrative founded on an inextricable dichotomy – that of the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. Of course this is intentionally socially divisive: it purposefully marginalises and stigmatises those needing support, while creating resentment among those who don’t.

The behaviourist perspective of structured ordeals as a deterrent is the same thinking that lies behind welfare sanctions, which are state punishments entailing the cruel removal of lifeline income for “non-compliance” in narrowly and rigidly defined “job seeking behaviours.” Sanctions are also described as a “behavioural incentive” to “help” and “encourage” people into work – the very language being used to describe the punitive actions of the state is also a nudge.

Behavioural linguistic techniques are being used to extend the view that state inflicted punishment is somehow in your best interests. It also serves to deny people’s accounts and experiences of punitive and unfair state interventions resulting in often harrowing adverse outcomes.

People who are ill, it is proposed, should be sanctioned, too, which would entail having their lifeline basic health care removed. Apparently, this stripping away of public services is also for our own good.

The welfare state originally arose to ensure citizens can meet their basic survival needs. Now it is assumed that those who need social security are psychologically abnormal or inept, and have fundamental character flaws (“undeserving”). Social security is no longer about ensuring minimal standards of living, the government is now preoccupied with disciplining the “feckless” poor, apparently aiming to punish them out of poverty.

On the face of it, welfare policy has been perceived over recent years as facing the challenge of balancing the three goals of keeping costs low, providing sufficient standards of living, and ensuring “work incentives.” This has sometimes been referred to as the “iron triangle” of welfare reform. The term reflects the difficult implicit trade-off between these three conflicting aims. It’s perceived that improvement of one dimension is usually gained only at the expense of weakening another.

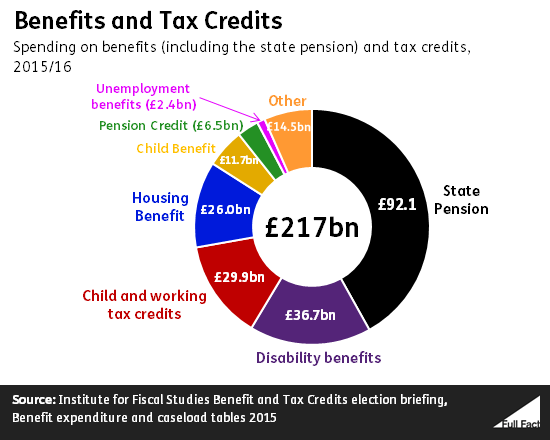

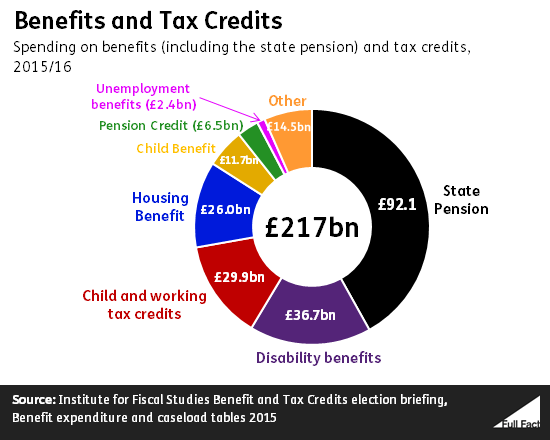

Neoliberal governments have tended to use aims one and three to justify the prioritisation of the second aim, which entails the lowering of costs “on the taxpayer” by lowering the standard of living for welfare recipients, in order to “incentivise” them to find work. The shift to behavioural explanations of poverty – that people need incentives to find a job in the first place – doesn’t, however, stand up to much scrutiny once we see that a large proportion of welfare spending actually goes towards supplementing low wages for those in work. The largest proportion of welfare spending is on pensions. The proportion of the welfare budget taken up by people who are unemployed is very small.

In the UK, the government have also introduced behaviourist in-work sanctions for people who “fail to progress” in work. Yet most wages are decided by employers, not employees. It’s not as if we have a government that values collective bargaining and the input of trade unions, after all. That’s a policy, therefore, that simply sets people up for sanctioning. It’s irrational and needlessly cruel.

It’s worth keeping in mind that social security constitutes a country’s lowest income security net. The levels of welfare benefits were originally calculated to meet only essential needs, providing sufficient income to cover the costs of just food, fuel and shelter, and are therefore directly related to the very minimum standards of living.

Criticism of the “scientific” methodology of behavioural economics: promoting neoliberal outcomes and neurototalitarianism

“Epistemic governance” refers to the cognitive and knowledge-related paradigms that underlie a society. Behavioural economists have presented randomised control trials (RCTs) as providing “naively neutral” evidence of what policy interventions work, but this is misleading. RCTs are advocated as an effective way of determining whether or not a particular intervention has been successful at achieving a specific outcome in a narrow context.

One concern about the use of RCTs in public policy-making is that this method is being promoted as the “gold standard” in a hierarchy of evidence that marginalises qualitative research. Quantitative methodology significantly reduces the scope for citizen feedback and detailed accounts of their experiences. The issues of interpretation and meaning are lost in the desire to “tame complexity with numbers”. Such a non-prefigurative (insofar as it is founded on hierarchical values and doesn’t tend to reflect cultural diversity), non-dialogic approach is profoundly incompatible with democratic principles.

As libertarian paternalism is specifically designed to lead to predetermined outcomes in terms of the behaviours it aims to produce – and it’s also constructed a rather miserable and prejudiced narrative of some humans’ cognitive capabilities (only poor people, reflecting traditional Conservative prejudices) – a major concern is that the predetermined structuring of choice, together with “re-normalisation” strategies, exclude the potential for public engagement and participation in debates concerning what choices and collective normative changes are actually beneficial, fair, desirable, appropriate, safe, right and wrong.

And of course, that raises a serious question about what constitutes “evidence”?

It’s not so long ago that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) manufactured evidence, using fake testimonies, claiming that people actually felt they had benefitted from welfare sanctions. Yet when pressed regarding the authenticity of the testimonies, the DWP then claimed:

“The photos used are stock photos and along with the names do not belong to real claimants. The stories are for illustrative purposes only. We want to help people understand when sanctions can be applied and how they can avoid them by taking certain actions. Using practical examples can help us achieve this.”

Those “testimonies” were neither practical nor genuine “examples”.

Academic research, statements from charities and support organisations, the evidence from the National Audit Office, and many individual case studies detailing severe hardship and harm to citizens because of welfare sanctions, have been presented to the government, all of which indicate that the use of financial penalties and harsh conditionality in administering social security does not help people into work. This evidence has been consistently discounted by the government, with claims that the statements are “politically biased” or that “no causal link between policy and adverse effects has been established”. The government have frequently dismissed citizens’ accounts of their harrowing experiences of sanctions as “anecdotal evidence”.

In this respect, libertarian paternalism may be seen as a form of neurototalitarianism. It’s a form of governance that imposes needs and requirements on citizens without any democratic engagement, without acknowledgement or recognition of citizen’s agency, identity, and their own self-defined needs.

Although advocates of RCTs have argued that this methodology excludes the unverified claims of “experts” in policy making, it ought to be noted that behavioural economists are nonetheless self-made “experts”, with their own technocratic language and mindset, and their “knowledge” of what human behaviours, cognitive strategies and perceptions are “optimal” and serve the “best interests” of the majority of citizens.

Behavioural economics isn’t “science”: it’s founded on a premise of economic moralism. Nudge is all about “encouraging” citizens to behave in social ways relying on market “incentives”, as opposed to regulations. It’s the invisible hand of the state, where increasing privatisation, deregulation, austerity and the shrinking state corresponds with increasing psychoregulation of citizens.

Yet if anything, behavioural economics has highlighted that the neoliberal state is fundamentally flawed – that there are major limitations of the magical thinking behind the “markets-know-best” politics.

In their critique of the economic rational-behaviour model, libertarian paternalists nonetheless advocate a perspective of rules, adjustments and remedies that ultimately serve to simply modify behaviours to fit the rational-behaviour model – which describes society in terms of self-interested individuals’ actions as explained through rationality, in which choices are consistent because they are made according to personal preference – to deliver the same neoliberal outcomes, by nudging public decision-making from that based on cognitive bias towards those decisions which are deemed cognitively rational. And what passes as “cognitively rational” is defined in terms of economic outcomes, by the neoliberal state.

This of course overlooks the limits on choice that neoliberal policies themselves impose, within in a system constrained by competitive individualism and “market forces”. It also assumes that the choice architects know what our best interests actually are.

The state is seen as acting to “re-rationalise” citizens: recalibrating perceptions, cognition and behaviours but without engaging with citizens’ rational processes. One criticism of behavioural economics is that it bypasses rational processes altogether, acting below our level of awareness, and as such, it doesn’t offer opportunities for learning and reflection. It’s more about a stimulus-response type of approach.

In a paper called Personal Responsibility and Changing Behaviour: the state of knowledge and its implications for public policy (Halpern et al., 2004) a group of libertarian paternalists, touting for business, outline a moral argument in which state policies increasingly should “cajole” people in the direction of personal responsibility and choice, since it is said that such an approach “strengthens individual character” and “moral capacity”, following a parental rationale of a distinctly Conservative disciplinary notion of “tough love” (p. 7).

A patchwork of theories on the ecology of behaviour change are discussed in the report: Ivan Pavlov and Burrhus Frederic Skinner’s outdated accounts of an authoritarian brand of behaviourism and conditioning, adaptation and rewards; Robert Cialdini’s business treatise on marketing, influence, compliance, and automatic behaviour patterns; the work of behavioural economists such as Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (1974) on heuristics; and community theories of behaviour, including concepts such as capability, social networks, social capital and social marketing (from Bourdieu, Coleman, Putnam – all cited in Halpern et al., 2004).

The role of the state here is seen not as a service provider to fulfil citizens’ needs, but as an “enabler”, and a public relations service for neoliberalism. The state has become an ultimate re-calibrator of citizens’ perceptions, attitudes, expectations, values and behaviours within the narrow confines of a neoliberal context.

Furthermore, Halpern says of nudge: “it enables public goods to be provided with a lower tax burden.” Describing tax as a “burden” is a form of default setting. Tax may also be seen as an essential public finance mechanism which is essential to economic and social development, providing sufficient revenue to support the productive and redistributive functions of the state. There is also an assumption that cheaper public goods are desirable, and will maintain their functional capacity and social benefits.

David Cameron’s “Big Society”, the Conservatives’ shift from a rights-based society, to one that entails “citizen responsibilities”, and of course their “low tax low, welfare” perspective are all designs from the libertarian paternalist’s template. Although nudge has been sold in the UK as a way of reducing state intervention, such policies have in reality become more about justifying the increasing intrusion of the state in our everyday life.

As I’ve hinted, nudge is about much more than changing behaviours based on cognitive bias to promote state defined citizens’ interests. It is also used to “reset” the public’s normative expectations, and for the promotion and inculcation of a fresh set of normative values of personal responsibility, self-help and self-discipline, claimed to be required in order to fulfil policy goals and justify interventions. Nudge is therefore reshaping public expectations regarding a “new relationship” between citizen and the state, where the burden of obligation is being increasingly and disproportionately placed on the poorest citizens.

Appeals to evidence-based policymaking are particularly misleading when they take out the context for interpreting specific forms of evidence. Libertarian paternalism is an imprecise theoretical approach to governance, and has resisted attempts to definitively codify its principles.

It seems to be a blend of social marketing techniques, psycholinguistics, psychographics, habituation and (re-)normalisation strategies. Libertarian paternalism draws heavily on psychology, capitalising on our dispositions, manipulating choices, perceptions and behaviours, by using a neuropolitical approach to fulfil neoliberal outcomes. Some of us have also dubbed this approach “neuroliberalism.”

Appeals to evidence in policymaking and debate are also frequently met with further questions on what sort of evidence counts, what it means – how the evidence is to be interpreted, what evidence is credible and importantly, how the policy question is defined and framed in the first place. As I’ve discussed, claims of “evidence” rest on tacit assumptions made in a specific context, so their transferability to another context is controversial.

Nudge fails to accommodate a range of diverse knowledge sources, public accounts and it does nothing to address the underlying assumptions embedded in behavioural economics, or those of policy-makers using it as a tool to fulfil their own aims and objectives, nor does it acknowledge its own limitations. It fails to acknowledge and reflect different epistemic (relating to knowledge and/or to the degree of its validation) and ethical concerns. Nudge doesn’t accommodate democratic dialogue with, and alternative accounts from, other experts, and most importantly, from citizens.

This means that any arising new evidence that may challenge the validity and reliability of behavioural economics theory is generally discounted, regardless of the nature and quality of that evidence. And a further problem is that new evidence also requires its own expert interpretation and assessment.

This is a key problem of epistemic governance. The production of evidence for policymaking should also be governed. Evidence is marshalled, interpreted and made to fit policy frameworks by experts. Those advocating the use of RCTs are experts, specialising in a highly codified form of knowledge, which is not easily accessible to the general public. The claim is that behavioural economics and the findings of RCTs are relevant to policy. This raises some fundamental questions, then, about who counts as an expert, what counts as expertise and similarly, we definitely need to keep asking: what does and does not count as evidence?

My point is that epistemic governance – the production of knowledge for governance – also needs be governed. It’s a point that others who research policy have also raised.

In order for research data to be of value and of use, it must be both reliable and valid. Reliability refers to the replicability and repeatability of findings. If the study were to be done a second time, would it yield the same results? If so, the data are reliable. If more than one person is observing behaviour or some event, all observers should agree on what is being recorded in order to claim that the data are reliable. Validity refers to the credibility of the research. Are the findings genuine? If a test is reliable, that does not mean that it is valid.

In order to determine cause and effect relationships, three basic conditions must be met:

- co-occurrence

- correct sequence or timing

- ruling out other explanations or “third factors/variables.”

The production of evidence, via testable hypotheses, to verify “knowledge” is insufficient if it is abstracted from the political context of policymaking in which problems are framed and knowledge is interpreted and given meanings.

I may have laboured the point, but it is a very important one. What counts as “evidence” is defined by the frame of reference, which also shapes which hypotheses are formulated and tested. I have already discussed how other forms of empirical evidence are discounted. The government have all too frequently used the quip “There is no evidence of causality between policy and stated events”.

Yet the Conservatives have refused to monitor the impact of their “reforms”, and have intentionally overlooked the important point that correlation often implies causation. Without conducting further investigation and examining the evidence, the government has no grounds whatsoever to dismiss the possibility of a causal relationship. It seems the government only value the principles of positivism when it comes to confronting other people’s knowledge and evidence that conflicts with their own.

Confirmation bias

To come at these problems from a slightly different angle, it’s worth considering the role of confirmation bias in knowledge production, which is the tendency to search for, select, favor, interpret new evidence as confirmation of one’s existing beliefs, expectations, prejudices, theories and hypotheses because we want them to be true. It is a type of cognitive bias and a systematic error of inductive reasoning.

Confirmation biases contribute to overconfidence (a person’s subjective confidence in his or her judgements is reliably greater than the objective accuracy of those judgements.) Iain Duncan Smith provided many memorable examples of cognitive bias. In July 2013, Duncan Smith was found by Andrew Dilnot, then Head of the UK Statistics Authority, to have broken their Code of Practice for Official Statistics for his and the DWP’s use of figures in support of, and to justify government policies.

Dilnot also stated that, following an earlier complaint about the handling of statistics by Duncan Smith’s Department, he had previously been told: “that senior DWP officials had reiterated to their staff the seriousness of their obligations under the Code of Practice and that departmental procedures would be reviewed”.

Duncan Smith’s defence was that: “You cannot absolutely prove those two things are connected – you cannot disprove what I said. I believe this to be right.” Pseudoscience has thrived using similar arguments: propositions are presented as fact and assumed to be true unless you can actually prove otherwise. Unicorns, telekinesis, gnomes and angels exist because I can’t prove they don’t.

This led Jonathan Portes, director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research and former chief economist at the Cabinet Office, to accuse the Conservative Party of going beyond spin and the normal political practice of cherry picking of figures, to the act of actually “making things up” with respect to the impact of government policy on employment and other matters.

“I believe I’m right” is an example of someone more certain that they are correct than they deserve to be, and this authoritarian approach can maintain or even strengthen beliefs in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It demonstrates a government that is simply digging in the trenches of ideology.

Flawed decision-making due to such biases have commonly arisen in political and organisational contexts. Yet it is public, not political behaviours, that have come to be regarded as “adaptive” to fit highly partisan political frames of reference. Apparently it’s only citizens who make mistakes in their decision-making, and whose behaviours need to be rectified.

We are being told that a lot of what we think is wrong. This is the foundation on which the shift in political emphasis from macro-level interventions to micro-level psychointerventions rests. Yet without exploring alternative and comparative forms of knowledge, this is simply conjecture in justification of the mass provision of state perceptions, behaviours and endorsed lifestyles, not verified fact.

Nudging neoliberalism

Behavioural economics has roots in the work of Herbert Simon – another winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1978 – on “bounded rationality” and grew enormously under the attention of Daniel Kahneman – another Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences winner – and Amos Tversky (1979), who argued that there are two broad features of human judgment and decision-making: various errors in coding mechanisms known as heuristics and biases, that lead to violations of the “laws” of logic and consistency. All of which differs from the neoclassical rational choice economic model, which portrays self-interested actors making rational choices in the market place.

The prize in Economics is not one of the original Nobel Prizes, it wasn’t bequeathed by and instituted through Alfred Nobel‘s will. It was controversially established in 1968 through a donation from the Swedish Central Bank, on the bank’s 300th anniversary. In the late 1960s, Sweden’s central bank was actively campaigning for the country to pursue a more “market-friendly” approach, and the prize, which was established in 1968 to commemorate the bank’s 300th anniversary, became a tool with which to support this campaign. Of course, the prize gives economists a stamp of approval for the general public and politicians alike, legitimising their entire philosophy.

Of the 74 laureates so far, 28 are affiliated with the University of Chicago, home of neoliberalism. Among those 28 winners are the early champions of neoliberalism, such as Milton Friedman and Friedrick Hayek. In fact the award has continually reinforced an ideology of the primacy of the “free market.” Hayek and Friedman lent great prestige to the cause of neoliberalism, which has contributed greatly to the creation of a rightward shift in the intellectual and political climate in western democracies.

Conservatives since Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan have been powerfully influenced by neoliberal economists. Thatcher’s first encounter with Hayek, for example, came when he published The Road to Serfdom in 1944. She read it as an undergraduate at Oxford, where it became a formative part of her authoritarian, distinctive and enduring outlook. She was radicalised at the age of 18.

One area of influence on Thatcher’s New Right policy in particular was Hayek’s low regard of trade union power and collective wage bargaining, he saw it as the primary reason for the UK’s economic difficulties (inflation) during the 70s, stating:

“There can indeed be little doubt to a detached observer that the privileges then granted to the trade unions have become the chief source of Britain’s economic decline.”

The incoming Labour government in 1974 were also blamed for failing to curb the unions during the inflation crisis. However, major contributing factors to the growth of inflation were rapidly rising oil prices, which increased by 70%, tripling in the early 1970s, and the “Barber Boom and Bust”. In the 1972 budget, the Conservative chancellor, Anthony Barber, oversaw a major deregulation and liberalisation of the banking system, replaced purchase tax and Selective Employment Tax with Value Added Tax, and also relaxed exchange controls.

During his term, the economy suffered due to stagflation and industrial unrest, including a miners strike which led to the Three-Day Week. In 1972 he delivered a budget which was designed to return the Conservatives to power in an election expected in 1974 or 1975. This budget led to a period known as “The Barber Boom”.

The measures in the budget, which included a growth in credit (due to bank deregulation and liberalisation) and consumer spending, which helped create a consumer bubble, led to high inflation, rising living costs and subsequent wage demands from public sector workers. The Conservatives, however, were not returned to office, and Labour were left to deal with rising inflation subsequently, until Thatcher’s government took office.

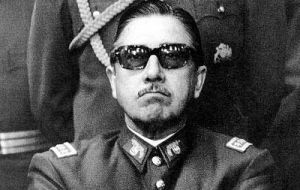

Hayek pressed Thatcher to quickly cut public expenditure, urging her to balance the budget in one year rather than five – and (unbelievably) to follow more closely the example of Pinochet’s Chile.

Under successive Conservative governments, and to some extend, under Blair’s New Labour, our society has been increasingly organised on overarching and totalising neoliberal principles. Socioeconomic conditions in the UK have fostered a hierarchical, unequal, competitive and above all, adversarial society, for many.

Wealth is a private matter, whereas “national debt” has become public responsibility. The poorest citizens carry the largest burden of the debt, under the guise of austerity, which, the government claim, is an economic “necessity.” We are told there is no alternative. Any challenge to this ideological preference is met with contempt, and derisive comments that any policy entailing a shift from free market thinking and competitive individualism towards a more equitable, collectivist socioeconomic organisation is economically “incompetent”, “dangerous” and would require a “magic money tree” to “fund” it. Neoliberalism is held up as the ONLY choice we have regarding our socioeconomic organisation. Behavioural economics simply endorses and extends this hegemonic view.

Austerity is actually central to neoliberal economic strategy, and is one consequence of right-wing libertarian “small state” dogma. Paradoxically, the role of the Conservative state has expanded rather than shrank, and is now all about enforcing public compliance and conformity within a socioeconomic system that is failing them, and the maintenance of strategies of fear, diversion, disempowerment, social divisions, a politically manufactured “scarcity”, a lowering of public expectations and the formulation of “deterrents.” And the institutionalisation of techniques of persuasion, public relations strategies and propaganda, to prop up and maintain the status quo.

The Conservative’s answer to the social injuries inflicted by their overarching, aggressive neoliberalism is to apply the sticking plaster of more increasingly aggressive neoliberalism.

The behaviourist turn reflects a subtle form of psychoauthoritarianism, which is all about enforcing neoliberalism.

Some people were critical of the fact that Hayek shared the 1974 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with Gunnar Myrdal for his “pioneering work in the theory of money and economic fluctuations and … penetrating analysis of the interdependence of economic, social and institutional phenomena.” Milton Friedman was awarded the 1976 prize in part for his work on monetarism. Awarding the prize to Friedman caused international protests. Friedman was accused of supporting the military dictatorship in Chile because of the relationship of economists of the University of Chicago to Pinochet.

Nudge is a technocratic and authoritarian solution to the terminal condition of neoliberalism. Nudge is being used to prop up a failing brand of particularly virulent Conservative end-stage capitalism. It’s basically the PR, packaging, marketing and advertising industry for, and enforcement of, neoliberalism. Because neoliberalism can’t sell itself to the public.

Ask General Augusto Pinochet. He used the “caravan of death” method of selling the “economic miracle” – neoliberalism – to the populace of Chile. He felt that in order to market the market economy, he simply had to kill all of his political opponents. The Rettig Commission puts the count of murdered individuals at approximately 3,000 during the 17-year Pinochet’s military junta.

Behavioural economics provides the government with more subtle form of authoritarianism that is about psychological coercion. But citizens are nonetheless dying as a consequence of government policies.

Technocracy

Although traditionally, decisions made by technocrats are based on information derived from methodology rather than opinion, in the UK, behavioural economists, or at least those using behavioural economics in policy, tend to make decisions derived from ideology.

Technocracy became a popular movement in the United States during the Great Depression when it was held that technical professionals, like engineers and scientists, would have a better understanding than politicians regarding the economy’s inherent complexity. Technocracy often arises during economically turbulent periods. In the states, we saw the rise of cybernetic and system models of society, from the likes of Talcott Parsons.

We also saw the development of political behaviouralism, a political pseudoscience that did not represent or reflect “genuine” political research. Instead, empirical consideration took precedence over normative and moral examination of politics. (See the is/ought distinction and naturalistic fallacy for further discussion on the key problems with this approach.)

Behaviouralism emphasised “an objective, quantified approach” to explain and predict political behaviours. It is associated with the rise of the behavioural sciences, modelled after the natural sciences. Behaviouralists also claimed they can explain political behaviour from an “unbiased, neutral” point of view.

Of course, behaviouralism is often most often attributed to the work of University of Chicago professor Charles Merriam who wrote in the 1920s and 1930s following the Great Depression.

The more things change, it seems the more they stay the same.

Behaviouralism was also founded on an insistence on distinguishing between facts and values. Quantitative evidence versus the abstract and the “anecdotal”. Sound familiar?

However, there’s also a difference between facts and meanings, human behaviours are meaningful and purposeful, human agency arises in contexts of intersubjectively shared meanings, from which there is no cultural or mind-independent, objective vantage point from which we may observe with value neutrality. And surely, abstract values such as “freedom”, “democracy” and “equality” are necessarily central to political discourse. Democratic politics must necessarily draw on the qualitative and the normative dimensions of social realities.

Behaviouralism was an inevitable consequence of positivism. Auguste Comte (1798-1857,) who was regarded by many as the founding father of social sciences, particularly sociology, and who coined the term “positivism,” was a Conservative. He believed social change should happen only as part of an organic, gradual evolutionary process, and he placed value on traditional social order, conventions and structures. Although the notion of positivism was originally claimed to be about the sovereignty of positive (verified) value-free, scientific facts, its key objective was politically Conservative. Positivism in Comte’s view was “the only guarantee against the communist invasion.” (Therborn, 1976: 224).

The thing about the fact-value distinction is that those who insist on it being rigidly upheld the most generally tend to use it the most to disguise their own whopping great ideological commitments. In psychology, we call this common defence mechanism splitting. It’s a very traditionally Conservative way of rigidly demarcating the world, imposing hierarchies of ranking, priority and order, to assure their own ontological security and maintain the status quo, regardless of how absurd this shrinking island of certainty appears to the many who are exiled from it.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Comte’s starting point is the same as Hayek’s, (another Nobel prize economist), namely the existence of a spontaneous order. It’s a Conservative ideological premise, and this is one reason why the current neoliberal government embrace the notion of positivism without any acknowledgement of its controversies.

Behaviouralism was a political, not a scientific concept. Moreover, since behaviouralism is not a research tradition, but a political movement, definitions of behaviouralism follow what behaviouralists wanted. Behaviouralists believe “truth or falsity of values (such as democracy, equality, and freedom, etc.) cannot be established scientifically and are beyond the scope of legitimate inquiry. They are therefore dismissed from legitimate consideration.

Christian Bay believed behaviouralism was a pseudopolitical science and that it did not represent “genuine” political research. Bay objected to empirical consideration taking precedence over normative and moral examination of politics.

In sociology, interpretivist researchers assert that the social world is fundamentally unlike the natural world insofar as the social world is meaningful in a way that the natural world is not. As such, social phenomena cannot be studied in the same way as natural phenomena. Interpretivism is concerned with generating explanations and extending understanding rather than simply describing, ranking and measuring social phenomena, and establishing basic cause and effect relationships.

Behaviouralism initially represented a movement away from “naive empiricism“, but as an approach, it has been criticised for its naive scientism. Additionally, some critics believe that the separation of fact from value makes the empirical study of politics impossible.

Positivist politics was discarded half a century ago, as a reactionary and totalitarian doctrine. It is true to say that, in many respects, Comte was resolutely anti-modern, and he also represents a general retreat from Enlightenment humanism. His somewhat authoritarian positivist ideology, rather than celebrating the rationality of the individual and wanting to protect people from state interference, instead fetishised the scientific method, proposing that a new ruling class of authoritarian technocrats should decide how society ought to be run, and how people should behave.

Which brings us back to the present. This is a view that the current government, with their endorsement and widespread experimental application of nudge theory, would certainly subscribe to.

History has witnessed the “scientific” theories of Darwin politically caricatured and applied to policy-making and society. We also witnessed the terrible conclusion of social Darwinism, as it inspired and underpinned the eugenics movement, which clearly played a critical role in the terrible genocide programmes, instigated and implemented by the technocratic government in Nazi Germany.

Leading Nazis, and early 1900 influential German biologists, revealed in their writings that Darwin’s theory and publications had a major influence upon Nazi race policies. The ideal that “all people are created equal”, which came to dominate Western ideology through human rights legislative frameworks, arising following the Second World War in response to the atrocities, has not been universal or constant among nations and cultures. Now, here in the UK, it has once again been replaced by neoliberal ideals of market place individualism and competition for “scarce” resources.

The first formulation of the term “Nudge” and associated principles was developed in cybernetics by James Wilk around 1995 and described by Brunel University academic D. J. Stewart as “the art of the nudge” (sometimes referred to as micronudges.)

Nudge is founded on a variety of cognitive theories, and its methodology has been largely experimental. (See The new Work and Health Programme: government plan social experiments to “nudge” sick and disabled people into work, for example.)

However, important questions have been raised about this approach as it has been advanced in both theory and practice. The recent adoption of wholesale experimentation by governments on a naive public, for example by the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team, the government of New South Wales, and others (Haynes et al, 2012) has attracted attention. In particular, the ethical implications of conducting experiments and the practical issues of their implementation raise important challenges around the maintenance of internal and external validity and the often competing demands of scientists and political decision-makers.

Behavioural economics has been used as a political legitimation of punitive welfare policies, entailing the removal of support for food, fuel and shelter, in the form of welfare sanctions. The government have refused to listen to evidence that challenges the basis of their justification. Nudge is being used as an authoritarian tool to ensure public conformity with inhumane policies and a neoliberal agenda.

It also extends a supremacist view, in that the public are regarded as “cognitively incompetent”, the theories rest on the assumption that most people don’t know how to act in their own best interests, whatever those interests may be. Yet those formulating the nudges are somehow adept at making decisions and at deciding what is in our “best interests”.

The coming of the policy lab and the legitimisation of political experimentation

Psychopolicy platforms are not simply the owners of information but are fast becoming owners of the infrastructures of society, too. Nudge has become a prop for neoliberal hegemony and New Right Conservative ideology. It’s become a technocratic fix – pseudo-psychology that doubles up as “common sense”, aimed at maintaining the socioeconomic order. It’s become a naturalised approach to public policy.

How can behavioural economists claim objectivity when they are active participants within the (intersubjectively constructed) cultural, political, economic and social environment, sharing the same context that allegedly shapes everyone else’s perceptions, conceptions, cognitive capacities and behaviours?

How exactly does behavioural economics itself miraculously transcend the reductionist and deterministic confines of bounded rationality, cognitive bias, and escape the stimulus-response chain? If all behaviours are determined, then so are political, psychological and economic theories and policies. And so is the pursuit of “objective” evidence.

As well as shaping behaviour, the psychopolitical messages being disseminated are all-pervasive, entirely ideological and not verifiably or reliably rational: they reflect and are shaping, for example, an anti-welfarism that sits with Conservative agendas for welfare “reform”, austerity, the “efficient” small state and also, are being used to legitimise these policy directions. Behavioural economics theory is even being used to “re-educate” our children as to how and who they should be.

Public and “social innovation” labs are enjoying enormous and lucrative political popularity. Nesta’s Innovation Lab has become a key player in the global circulation of policy lab ideas, and a connective node in a variety of lab networks. The Cabinet Office has established Policy Lab UK, a lab at the centre of government. GovLab in New York, MindLab in Denmark, and many others are now part of a global movement of organisations seeking to apply “radically new methods” to the practices of government

Social-emotional learning (SEL) encompasses concepts such as character, education, growth, mindset, “resilience”, “grit”, perseverance, so-called non-cognitive or non-academic and other mass marketed traditional and ghastly public school values, “personal qualities” and “competences.”

In the last couple of years, social-emotional learning has emerged as a key policy priority from the work of international policy influencers such as the OECD and World Economic Forum; psychological entrepreneurs such as Angela Duckworth’s “Character Lab” and Carol Dweck’s “growth mindset” work; venture capital-backed philanthropic advocates (e.g. Edutopia); powerful lobbying coalitions (CASEL) and institutions (Aspen Institute) and government agencies and partners, especially in the US (for example, the US Department of Education “grit” report of 2013) and in the UK: in 2014 an all-party parliamentary committee produced a sanctimonious “Character and Resilience Manifesto” in partnership with the Centre Forum think tank, with the Department for Education following up with funding for schools to outsource the development of character education programmes.

Apparently social mobility depends on the characters of people in a society, and has nothing to do with access to opportunities and socioeconomic inequalities. The Manifesto says: “Character and Resilience are major factors in social mobility but are often overlooked in favour of things which are more tangible and easier to measure.” Or more obvious and strongly correlated.

Social-emotional learning theory is the product of a fast policy network of “psy” entrepreneurs, global policy advice, media advocacy, philanthropy, think tanks, technology research and development and venture capital investment.

Together, this alliance have produced shared narratives and vocabularies, aspirations, and offers techniques of quantification of the “behavioural indicators” of classroom behaviours that correlate to psychologically defined categories of character, mindset, grit, and other personal qualities defined by social-emotional learning theory.

As Agnieszka Bates has argued in The management of ‘emotional labour’ in the corporate re-imagining of primary education in England, that psychological advocates of SEL have conceptualized character as determined, but malleable, as well as measurable. SEL defines and manages the character skills that are most valuable to the labour market. As such, she describes SEL as a psycho-economic fusion of economic goals and psychological discourse in a corporatized education system. Specific algorithms and metrics have already been devised by prominent psycho-economic centres of expertise to measure the economic value of social-emotional learning.

Policies that prioritise “resilience” tend to put the onus of inequalities, poverty and other difficult circumstances and disaster responses on individuals rather than collective, publicly coordinated efforts. Tied to the emergence of neoliberal discourse, the political promotion of individual citizens’ resilience diverts attention away from governmental responsibility and towards localised, laissez-faire responses. How the term “resilience” or “grit” is defined affects research focuses; different or insufficient definitions will lead to inconsistent research about the same concepts.

Research on resilience has become more heterogeneous in its outcomes and measures, convincing some researchers to abandon the term altogether due to it being attributed to all outcomes of research where results were more positive than expected. Other researchers have pointed to cultural relativity, for example, in the area of indigenous health, where they have shown the impact of culture, history, community values, and geographical settings on resilience in indigenous communities.

Another problem with this type of character education is that it promotes an amoral and careerist “looking out for number one” perspective. This is simply neoliberal competitive individualism in the guise of psychological constructs, rather than being tethered to, say, social conscience or moral imperatives. Achievement is narrowly defined as an endless competition for money, status, highly specific types of “success” and the next win.

It’s an important distinction, because while it’s fair to acknowledge that it takes grit, courage and self-control to be a successful doctor, teacher or social worker, exactly the same could be said about a suicide bomber or mass murderer. I‘m sure many psychopaths and villians would have scored extremely well in such character assessments, being gritty, extremely hard-working, resilient, supremely self-controlled, charming and wildly optimistic.

Empathy, justice, collectivism and public service seem to be conspicuously absent in the educational shopping list of desirable dog eat dog character traits.

It’s difficult to miss the major influence of Martin Seligman and Christopher Peterson’s Character Strengths and Virtues, which was a major contribution to the methodological study of “positive psychology,” embedded in SEL. Given their focus on “improving human functioning” and “wellbeing”, positive psychology is closely related to “coaching psychology.”

However, Seligman and Peterson’s 24 “character strengths” were derived from religious and philosophical texts, and not from empirical evidence or scientific discourse, it could be argued that opinion has shaped research here rather than research shaping opinion. Furthermore, most of the 24 strengths do not have significant association with all positive outcomes and various studies yield contradictory results. Additionally, some empirical studies show that development of some character strengths can lead to degradation of other strengths.

In Positive Psychology: A Foucauldian Critique, Matthew McDonald and Jean O’Callahan argue that the “character strength” approach reflects a new political system of surveillance that risks creating an unintended consequence: disillusionment and alienation in much the same way that the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) has achieved by marginalising those whose characters do not conform to society’s norms”. Moreover, it is a new regulatory tool for selection, control, and discrimination in the workplace, just as “personality measures” have been used in the past.

The authors further argue that such an approach may influence organisational culture by manipulating employee identity to control and coerce their workforce into more productive modes of functioning. Finally, they believe that Strength-Approaches support neoliberalism in treating the social domain as an economic domain, to promote self-governance, self-reliance and thus serves as tool in the implementation of current workplace policy and welfare “reform” in a number of Western nations, especially the US and UK.

The authors say that positive psychology privileges particular modes of functioning by classifying and categorising character strengths and virtues, supporting a neoliberal economic and political discourse, and has an “adversarial dialogue, with humanistic psychology.”

Central to antihumanism more generally is the view that concepts of “human nature” “man”, or “humanity” should be rejected as historically relative or metaphysical. Nietzsche argues in Genealogy of Morals that human rights exist as a means for the weak to constrain the strong; as such, they do not facilitate the emancipation of life, but instead, deny it.

However, human rights were formulated to ensure that the powerful are accountable to citizens, and promote the idea that all life has equal worth, regardless of social status. “Constraining” genocide is not only acceptable, it’s desirable.

Humanist Tzvetan Todorov identified within modernity a trend of thought which emphasises science and within it, the trend towards a deterministic view of the world. He clearly identifies positivist theorist Auguste Comte as an important proponent of this view.

For Todorov “Scientism does not eliminate the will but decides that since the results of science are valid for everyone, this will must be something shared, not individual. In practice, the individual must submit to the collectivity, which “knows” better than he does.” The autonomy of the will is maintained, but it is the will of the group, not the person…scientism has flourished in two very different political contexts…The first variant of scientism was put into practice by totalitarian regimes.” (The Imperfect Garden. 2001. Pg. 23)

Positivism is a form of epistemological totalitarianism. It is an outdated view that society, like the physical world, operates according to general laws, and that all authentic knowledge is that which is verified.

However, the verification principle is itself unverifiable.

Positivism tends to present superficial and descriptive rather than meaningful, in-depth and explanatory accounts of social events and phenomena. In psychology, behaviourism has been the doctrine most closely associated with positivism. Behaviour from this perspective can be described and explained without the need to make ultimate reference to mental events, emotions or to internal psychological processes. Psychology is, according to behaviourists, the isolated “science” of behaviour, and not the mind.

This approach, which has no regard for human reasoning, meanings and phenomenological experience, is echoed in behavioural economics, which generally doesn’t engage with people at the level of conscious awareness and rationality. It is claimed that nudges only work “in the dark,” as it were.

While positivists more generally locate causal relationships at the level of observable surface events, critical realists locate them at the level of deeper, underlying generative mechanisms. For example, in science, gravity is an underlying mechanism that is not directly observable, but it does generate observable effects. In sociology, on a basic level, Marx’s determining base (which determines superstructure) may be regarded as a generative mechanism which gives rise to emergent and observable properties.

A RCT is a positivist research model in which people are randomly assigned to an intervention or a control (a group with no intervention) and this allows narrow comparisons to be made. Widely accepted as the “gold standard” for clinical trials, the foundation for evidence-based medicine, RCTs are used to establish causal relationships. These kinds of trials usually have very strict ethical safeguards to ensure the fair and ethical treatment of all participants, and these safeguards are especially essential in government trials, given the obvious power imbalances and potential for abuse. A basic principle expressed in the Nuremberg Code is the respect due to persons and the value of a person’s autonomy. And life.

Epistemology is the study or theory of the nature and grounds of knowledge, especially with reference to its limits, reliability and validity. It’s invariably linked with how a researcher perceives our relationship with the world and what “social reality” is (ontology), and how we ought to investigate that world (methodology).

For example, in sociology, some theorists hold that social structures largely determine our behaviour, and so behaviour is predictable and objectively measurable, others emphasise human agency, and believe that we shape our own social reality to a degree, and that it’s mutually and meaningfully negotiated and unfixed. Therefore, detail of how we make sense of the world and navigate it is crucially important, and so is the context. Behavioural economics and any form of epistemic governance must surely accommodate and reflect this complexity and plurality of perspective.

Neoliberalism is failing. It’s not failing because populations lack rationality, cognitive capacity or “character”: it’s failing because neoliberalism itself doesn’t accommodate and reflect rationality, nor does it fulfil even basic public needs. It places limits on human development and stifles potential.

The political response is also irrational and reflects cognitive bias. The response, so far, has been aimed at coercing citizens to “adapt” to a failing socioeconomic policy framework, rather than to change the framework itself.

I don’t make any money from my work. I am disabled because of illness and have a very limited income. But you can help by making a donation to help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.