I’ve read the government’s Work, health and disability green paper: improving lives and consultation from end to end. It took me a while, because I am ill and not always able to work consistently, reliably and safely. It’s also a very long and waffling document. I am one of those people that the proposals outlined in this green paper is likely to affect. I read the document very carefully.

Here are a few of my initial thoughts on what I read. It’s organised as best I can manage, especially given the fact that despite being dismally unsurprised, I am scathing.

The context indicates the general intent

“The fact is that Ministers are looking for large savings at the expense of the poorest and most vulnerable. That was not made clear in the general election campaign; then, the Prime Minister said that disabled people would be protected.” – Helen Goodman, MP for Bishop Auckland, Official Report, Commons, 2/3/16; cols. 1052-58.

I always flinch when the government claim they are going to “help” sick and disabled people into work. That usually signals further cuts to lifeline support and essential services are on the way, and that the social security system is going to be ground down a little further, to become the dust of history and a distant memory of a once civilised society.

If the government genuinely wanted to “help” sick and disabled people into work, I’m certain they would not have cut the Independent Living Fund, which has had a hugely negative impact on those trying their best to lead independent and dignified lives, and the Access To Work funding has been severely cut, this is also a fund that helps people and employers to cover the extra living costs arising due to disabilities that might present barriers to work.

The government also made the eligibility criteria for Personal Independence Payment (PIP) – a non-means tested out-of- work and an in-work benefit – much more difficult to meet, in order to simply reduce successful claims and cut costs. This has also meant that thousands of people have lost their motability vehicles and support.

Earlier this year, it was estimated at least 14,000 disabled people have had their mobility vehicle confiscated after the changes to benefit assessment, which are carried out by private companies.

Under the PIP rules, thousands more people who rely on this support to keep their independence are set to lose their vehicles – specially adapted cars or powered wheelchairs. Many had been adapted to meet their owners’ needs and many campaigners warn that it will lead to a devastating loss of independence for disabled people.

A total of 45% or 13,900 people, were deemed as not needing the higher rate of PIP, and therefore lost their vehicles after reassessment. And out of the 31,200 people who were once on the highest rate of Disability Living Allowance (DLA) who have been reassessed, just 55%, or 17,300 – have kept their car.

In 2012, Esther McVey, then the Minister for people with disabilities, as good as admitted there are targets to reduce or remove eligibility for the new disability benefit PIP, which was to replace DLA. How else could she know in advance of people’s reassessment that “330,000 of claimants are expected to either lose their benefit altogether or see their payments reduced“ as she had informed the House of Commons.

This was a clear indication that the new assessment framework was designed to cut support for disabled people. A recent review led the government to conclude that PIP doesn’t currently fulfil the original policy intent, which was to cut costs and “target” the benefit to an ever-shrinking category of “those with the greatest need.”

The Government was twice defeated in the Lords over their proposals to cut Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) for sick and disabled people in the work related activity group (WRAG) from £103 to £73. However the £30 a week cut is to go ahead after bitterly disappointed and angry peers were left powerless to continue to oppose the Commons, which has overturned both defeats.

The government hammered through the cuts of £120 a month to the lifeline income of ill and disabled people by citing the “financial privilege” of the Commons, and after Priti Patel informing the Lords, with despotic relish, that they had “overstepped their mark” in opposing the cuts twice.

A coalition of 60 national disability charities condemned the government’s cuts to benefits as a “step backwards” for sick and disabled people and their families. The Disability Benefits Consortium said that the cuts, which will see people lose up to £1,500 a year, will leave disabled people feeling betrayed by the government and will have a damaging effect on their health, finances and ability to find work.

Research by the Consortium suggests the low level of benefit is already failing to meet disabled people’s needs. A survey of 500 people in the affected group found that 28 per cent of people had been unable to afford to eat while in receipt of the benefit. Around 38 per cent of respondents said they had been unable to heat their homes and 52 per cent struggled to stay healthy.

Watching the way the wind blows

Earlier this year I wrote that a government advisor, who is a specialist in labor economics and econometrics, has proposed scrapping all ESA sickness and disability benefits. Matthew Oakley, a senior researcher at the Social Market Foundation, recently published a report entitled Closing the gap: creating a framework for tackling the disability employment gap in the UK, in which he proposes abolishing the ESA Support Group.

To meet extra living costs because of disability, Oakley says that existing spending on PIP and the Support Group element of ESA should be brought together to finance a new extra costs benefit. Eligibility for this benefit should be determined on the basis of need, with an assessment replacing the WCA and PIP assessment.

I think the word “need” is being redefined to meet politically defined neoliberal economic outcomes.

Oakely also suggests considering a “role that a form of privately run social insurance could play in both increasing benefit generosity and improving the support that individuals get to manage their conditions and move back to work.”

I’m sure the rogue company Unum would jump at the opportunity. Steeped in controversy, with a wake of scandals that entailed the company denying people their disabilty insurance, in 2004, Unum entered into a regulatory settlement agreement (RSA) with insurance regulators in over 40 US states. The settlement related to Unum’s handling of disability claims and required the company “to make significant changes in corporate governance, implement revisions to claim procedures and provide for a full re-examination of both reassessed claims and disability insurance claim decisions.

The company is the top disability insurer in both the United States and United Kingdom. By coincidence, the company has been involved with the UK’s controversial Welfare Reform Bill, advising the government on how to cut spending, particularly on disability support. What could possibly go right?

It’s difficult to see how someone with a serious, chronic and progressive illness, (which most people in the ESA Support Group have) can actually “manage” their illness and “move back into work.” The use of the extremely misinformed, patronising and very misleading term manage implies that very ill people actually have some kind of choice in the matter.

For people with Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus and multiple sclerosis, cancer and kidney failure, for example, mind over matter doesn’t fix those problems, positive thinking and sheer will power cannot cure these illnesses, sadly. Nor does refusing to acknowledge or permit people to take up a sick role, or imposing benefit conditionality and coercive policies to push chronically ill people into work by callous, insensitive and inept and often medically unqualified assessors, job advisors and ministers.

The Reform think tank has also recently proposed scrapping what is left of the disability benefit support system, in their report Working welfare: a radically new approach to sickness and disability benefits and has called for the government to set a single rate for all out of work benefits and reform the way sick and disabled people are assessed.

The Reform think tank proposes that the government should cut the weekly support paid to 1.3 million sick and disabled people in the ESA Support Group from £131 to £73. This is the same amount that Jobseeker’s Allowance claimants receive. It is claimed that the cut will somehow “incentivise” those people to find work, as if they simply lack motivation, rather than being ill and disabled. However, those people placed in the Support Group after assessment have been deemed by the state as unlikely to be able to work again in the near future, many won’t be able to work again. It would therefore be very difficult to justify this proposed cut, given the additional needs that disabled people have, which is historically recognised, and empirically verified by research.

Yet the authors of the report doggedly insist that having a higher rate of weekly benefit for extremely sick and disabled people encourages them “to stay on sickness benefits rather than move into work.” People on sickness benefits don’t move into work because they are sick. Forcing them to work is outrageous.

The report recommended savings which result from removing the disability-related additions to the standard allowance should be reinvested in support services and extra costs benefits – PIP. However, as outlined, the government have ensured that eligibility for that support is rapidly contracting, with the ever-shrinking political and economic re-interpretation of medically defined sickness and disability categories and a significant reduction in what the government deem to be a legitimate exemption from being “incentivised” into hard work.

The current United Nations investigation into the systematic and gross violations of the rights of disabled people in the UK because of the Conservative welfare “reforms” is a clear indication that there is no longer any political commitment to supporting disabled people in this country, with the Independent Living Fund being scrapped by this government, ESA for the work related activity group (WRAG) cut back, PIP is becoming increasingly very difficult to access, and now there are threats to the ESA Support Group. The Conservative’s actions have led to breaches in the CONVENTION on the RIGHTS of PERSONS with DISABILITIES – CRPD articles 4, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, and especially 19, 20, 27 and 29 (at the very least.)

There are also probable violations of articles 22, 23, 25, 30, 31.

The investigation began before the latest round of cuts to ESA were announced. That tells us that the government is unconcerned their draconian policies violate the human rights of sick and disabled people.

And that, surely, tells us all we need to know about this government’s intentions.

Coercing those deemed to ill to work into work. It’s not “nudge”: it’s psycho-compulsion

The casual discussion in the green paper about new mandatory “health and work conversations” in which work coaches will use “specially designed techniques” to “help” some ESA claimants “identify their health and work goals, draw out their strengths, make realistic plans, and build resilience and motivation” is also cause for some concern.

Apparently these conversations were “co-designed with disabled people’s organisations and occupational health professionals and practitioners and the Behavioural Insights Team – the controversial Nudge Unit, which is part-owned by the Cabinet Office and Nesta.

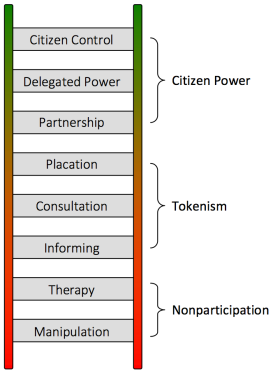

Most people who read my work regularly will know by now that I am one of the staunchest critics of nudge, which is being used as an antidemocratic, technocratic, pseudoscientific political tool to provide a prop and disguise for controversial neoliberal policies. It’s very evident that “disabled people’s organisations” were not major contributors to the design. It’s especially telling that those people to be targeted by this “intervention” were completely excluded from the conversation. Sick and disabled people are reduced to objects of public policy, rather than being seen as citizens and democratic subjects capable of rational dialogue.

John Pring at Disability News Service (DNS) adds: “Grassroots disabled people’s organisations (DPOs) have criticised the government’s decision to exclude them from an event held to launch its new work, health and disability green paper.

The event for “stakeholders” was hosted by the disability charity Scope at its London headquarters, and attended by Penny Mordaunt, the minister for disabled people.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) said in its invitation – it turned down a request from Disability News Service to attend – that the event would “start the consultation period” on its green paper, Improving Lives.

It said that it was “launching a new conversation with disabled people and people with health conditions, their representatives, healthcare professionals and employers”.

But DWP has refused to say how many disabled people’s user-led organisations were invited to the event, and instead suggested that DNS submit a freedom of information request to find out.

But DNS has confirmed that some of the most prominent user-led organisations with the strongest links to disabled people were not invited to the launch, including Shaping Our Lives, Inclusion London, Equal Lives, People First (Self Advocacy) and Disabled People Against Cuts.”

For further discussion of the policy context leading up to the green paper, see The new Work and Health Programme: government plan social experiments to “nudge” sick and disabled people into work from October 2015.

Also see G4S are employing Cognitive Behavioural Therapists to deliver “get to work therapy” and Stephen Crabb’s obscurantist approach to cuts in disabled people’s support and also Let’s keep the job centre out of GP surgeries and the DWP out of our confidential medical records from earlier this year.

The dismal and incoherent contents of the green paper were entirely predictable.

The Conservatives claim work is a “health” outcome: crude behaviourism

A Department for Work and Pensions research document published back in 2011 – Routes onto Employment and Support Allowance – said that if people believed that work was good for them, they were less likely to claim or stay on disability benefits.

It was then decided that people should be “encouraged” to believe that work was “good” for health. There is no empirical basis for the belief, and the purpose of encouraging it is simply to cut the numbers of disabled people claiming ESA by “encouraging” them into work. Some people’s work is undoubtedly a source of wellbeing and provides a sense of purpose. That is not the same thing as being “good for health”. For a government to use data regarding opinion rather than empirical evidence to claim that work is “good” for health indicates a ruthless mercenary approach to a broader aim of dismantling social security.

From the document: “The belief that work improves health also positively influenced work entry rates; as such, encouraging people in this belief may also play a role in promoting return to work.”

The aim of the research was to “examine the characteristics of ESA claimants and to explore their employment trajectories over a period of approximately 18 months in order to provide information about the flow of claimants onto and off ESA.”

The document also says: “Work entry rates were highest among claimants whose claim was closed or withdrawn suggesting that recovery from short-term health conditions is a key trigger to moving into employment among this group.”

“The highest employment entry rates were among people flowing onto ESA from non-manual occupations. In comparison, only nine per cent of people from non-work backgrounds who were allowed ESA had returned to work by the time of the follow-up survey. People least likely to have moved into employment were from non-work backgrounds with a fragmented longer-term work history. Avoiding long-term unemployment and inactivity, especially among younger age groups, should, therefore, be a policy priority. ”

“Given the importance of health status in influencing a return to work, measures to facilitate access to treatment, and prevent deterioration in health and the development of secondary conditions are likely to improve return to work rates”

Rather than make a link between manual work, lack of reasonable adjustments in the work place and the impact this may have on longer term ill health, the government chose instead to promote the cost-cutting irrational belief that work is a “health” outcome. Furthermore, the research does conclude that health status itself is the greatest determinant in whether or not people return to work. That means that those not in work are not recovered and have longer term health problems that tend not to get better.

Work does not “cure” ill health. To mislead people in such a way is not only atrocious political expediency, it’s actually downright dangerous.

As neoliberals, the Conservatives see the state as a means to reshape social institutions and social relationships based on the model of a competitive market place. This requires a highly invasive power and mechanisms of persuasion, manifested in an authoritarian turn. Public interests are conflated with narrow economic outcomes. Public behaviours are politically micromanaged. Social groups that don’t conform to ideologically defined economic outcomes are stigmatised and outgrouped.

Othering and outgrouping have become common political practices, it seems.

Stigma is a political and cultural attack on people’s identities. It’s used to discredit, and as justification for excluding some groups from economic and political consideration, refusing them full democratic citizenship.

Stigma is being used politically to justify the systematic withdrawal of support and public services for the poorest – the casualties of a system founded on competition for allegedly scarce wealth and resources. Competition inevitably means there are winners and losers. Stigma is profoundly oppressive.

It is used as a propaganda mechanism to draw the public into collaboration with the state, to justify punitive and discriminatory policies and to align citizen “interests” with rigid neoliberal outcomes. Inclusion, human rights, equality and democracy are not compatible with neoliberalism.

Earlier this year, I said: The Conservatives have come dangerously close to redefining unemployment as a psychological disorder, and employment is being redefined as a “health outcome.” The government’s Work and Health programme involves a plan to integrate health and employment services, aligning the outcome frameworks of health services, Improving Access To Psychological Therapies (IAPT), Jobcentre Plus and the Work Programme.

But the government’s aim to prompt public services to “speak with one voice” is founded on questionable ethics. This proposed multi-agency approach is reductive, rather than being about formulating expansive, coherent, comprehensive and importantly, responsive provision.

This is psychopolitics, not therapy. It’s all about (re)defining the experience and reality of a social group to justify dismantling public services (especially welfare), and that is form of gaslighting intended to extend oppressive political control and micromanagement. In linking receipt of welfare with health services and “state therapy,” with the single intended outcome explicitly expressed as employment, the government is purposefully conflating citizen’s widely varied needs with economic outcomes and diktats, isolating people from traditionally non-partisan networks of relatively unconditional support, such as the health service, social services, community services and mental health services.

Public services “speaking with one voice” will invariably make accessing support conditional, and further isolate already marginalised social groups. It will damage trust between people needing support and professionals who are meant to deliver essential public services, rather than simply extending government dogma, prejudices and discrimination.

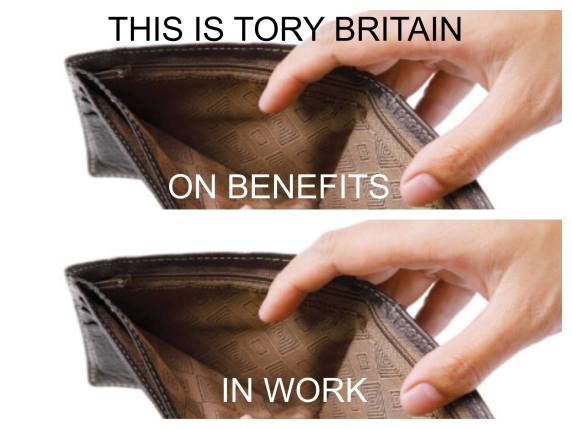

Conservatives really seem to believe that the only indication of a person’s functional capacity, value and potential is their economic productivity, and the only indication of their moral worth is their capability and degree of willingness to work. But unsatisfactory employment – low-paid, insecure and unfulfiling work – can result in a decline in health and wellbeing, indicating that poverty and growing inequality, rather than unemployment, increases the risk of experiencing poor mental and physical health. People are experiencing poverty both in work and out of work.

Moreover, in countries with an adequate social safety net, poor employment (low pay, short-term contracts), rather than unemployment, has the biggest detrimental impact on mental health.

There is ample medical evidence (rather than the current raft of political dogma) to support this account. (See the Minnesota semistarvation experiment, for example. The understanding that food deprivation in particular dramatically alters cognitive capacity, emotions, motivation, personality, and that malnutrition directly and predictably affects the mind as well as the body is one of the legacies of the experiment.)

Systematically reducing social security, and increasing conditionality, particularly in the form of punitive benefit sanctions, doesn’t “incentivise” people to look for work. It simply means that people can no longer meet their basic physiological needs, as benefits are calculated to cover only the costs of food, fuel and shelter.

Food deprivation is closely correlated with both physical and mental health deterioration. Maslow explained very well that if we cannot meet basic physical needs, we are highly unlikely to be able to meet higher level psychosocial needs. The government proposal that welfare sanctions will somehow “incentivise” people to look for work is pseudopsychology at its very worst and most dangerous.

In the UK, the government’s welfare “reforms” have further reduced social security support, originally calculated to meet only basic physiological needs, which has had an adverse impact on people who rely on what was once a social safety net. Poverty is linked with negative health outcomes, but it doesn’t follow that employment will alleviate poverty sufficiently to improve health outcomes.

In fact record numbers of working families are now in poverty, with two-thirds of people who found work in 2014 taking jobs for less than the living wage, according to the annual report from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation a year ago.

Essential supportive provision is being reduced by conditionally; by linking it to such a narrow outcome – getting a job – and this will reduce every service to nothing more than a political semaphore and service provision to a behaviour modification programme based on punishment, with a range of professionals being politically co-opted as state enforcers.

The Government is intending to “signpost the importance of employment as a health outcome in mandates, outcomes frameworks, and interactions with Clinical Commissioning Groups.”

I have pointed out previously that there has never been any research that demonstrates unemployment is a direct cause of ill health or that employment directly improves health, and the existing studies support the the idea that the assumed causality between unemployment and health may actually run in the opposite direction. It’s much more likely that inadequate social security support means that people cannot meet all of their basic survival needs (food, fuel and shelter), and that contributes significantly to poor health outcomes.

It’s not that unemployment is causing higher ill health, but that ill health and discrimination are causing higher unemployment. If it were unemployment causing ill health, at a time when the government assures us that employment rates are currently “the highest on record,” why are more people becoming sick?

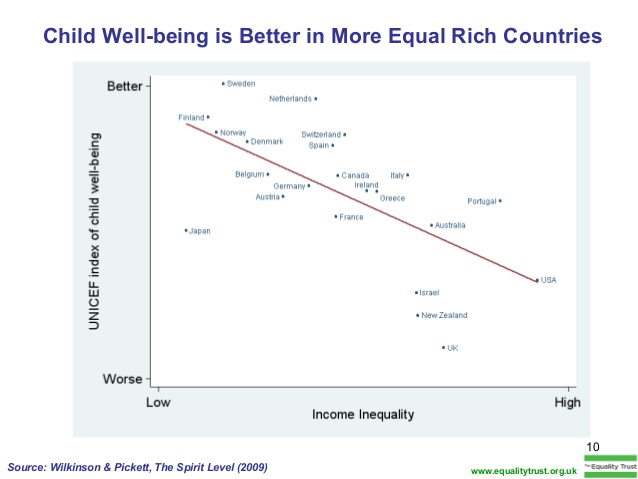

The answer is that inequality and poverty have increased, and these social conditions, created by government policies, have long been established by research as having a correlational relationship with increasing mental and physical health inequalities.

For an excellent, clearly written and focused development of these points, the problem of “hidden” variables and political misinterpretation, see Jonathan Hulme’s Work won’t set us free.

Semantic thrifts: being Conservative with the truth

Prior to 2010, cutting support for sick and disabled people was unthinkable, but the “re-framing” strategy and media stigmatising campaigns have been used by the Conservatives to systematically cut welfare, push the public’s normative boundaries and to formulate moralistic justification narratives for their draconian policies. Those narratives betray the Conservative’s intentions.

Not enough people have questioned what it is that Conservatives actually mean when they use words like “help”, “support”, and “reform” in the context of government policies aimed at disabled people. Nor have they wondered where the evidence of “help” and “support” is hiding. If you sit on the surface of Conservative rhetoric and the repetitive buzzwords, it all sounds quite reasonable, though a little glib.

If you scrutinise a little, however, you soon begin to realise with horror that Orwellian-styled techniques of neutralisation are being deployed to lull you into a false sense of security: the ideologically directed intentions behind the policies and the outcomes and consequences are being hidden or “neutralised” by purposefully deceptive, misdirectional political rhetoric. It’s a kind of glittering generalities tokenism ; a superficial PR ritual of duplicitous linguistic detoxification, to obscure deeply held traditional Conservative prejudices and ill intent.

Rhetoric requires the existence of an audience and an intent or goal in the communication. Once you stand back a little, you may recognise the big glaring discrepancies between Conservative chatter, policies, socioeconomic reality and people’s lived experiences. At the very least, you begin to wonder when the conventional ideological interests of the Conservatives suddenly became so apparently rhetorically progressive, whilst their policies have actually become increasingly authoritarian, especially those directed at the most disadvantaged social groups.

The ministerial foreword from Damian Green, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and Jeremy Hunt, Secretary of State for Health, is full of concern that despite the claim that “we have seen hundreds of thousands more disabled people in work in recent years”, there are simply too many sick and disabled people claiming ESA.

They say: “We must highlight, confront and challenge the attitudes, prejudices and misunderstandings that, after many years, have become engrained in many of the policies and minds of employers, within the welfare state, across the health service and in wider society. Change will come, not by tinkering at the margins, but through real, innovative action. This Green Paper marks the start of that action and a far-reaching national debate, asking: ‘What will it take to transform the employment prospects of disabled people and people with long-term health conditions?’”

I think mention of the “engrained attitudes, prejudices and misunderstandings within the welfare state and across the health service” is the real clue here about intent. What would have been a far more authentic and reassuring comment is “we have met with disabled people who have long-term health conditions and asked them if they feel they can work, and what they need to support them if they can.”

Instead, what we are being told via subtext is that we are wrong as a society to support people who are seriously ill and disabled by providing civilised health and social care, social security and exempting them from work because they are ill or injured.

Ministers say: “Making progress on the government’s manifesto ambition to halve the disability employment gap is central to our social reform agenda by building a country and economy that works for everyone, whether or not they have a long-term health condition or disability. It is fundamental to creating a society based on fairness [..] It will also support our health and economic policy objectives by contributing to the government’s full employment ambitions, enabling employers to access a wider pool of talent and skills, and improving health.”

I think that should read: “By building a country where everyone works for the [politically defined] economy.”

There’s patronising discussion of how disabled people should be “allowed to fulfil their potential”, and that those mythic meritocratic principles of talent determination and aspiration should be “what counts”, rather than sickness and disability. There are some pretty gaping holes in the logic being presented here. It is assumed that prejudice is the reason why sick and disabled people don’t work.

But it’s true that many of us cannot work because we are too ill, and the green paper fails to acknowledge this fundamental issue.

Instead “inequality” has been redefined strictly in terms of someone’s employment status, rather than as an unequal social distribution of wealth, resources, power and opportunities. All of the responsibility and burden of social exclusion and unemployment is placed on sick and disabled people, whilst it is proposed that businesses are financially rewarded for employing us.

Furthermore, it’s a little difficult to take all the loose talk seriously about the “injustice” of ill people not being in work, or about meritocratic principles and equal opportunities, when it’s not so long ago that more than one Conservative minister expressed the view that disabled people should work for less than the minimum wage. This government have made a virtue out of claiming they are giving something by taking something away. For example, the welfare cuts have been casually re-named reforms in Orwellian style. We have yet to see how cutting the lifeline benefits of the poorest people, and imposing harsh sanctioning can possibly be an improvement for them, or how it is helping them.

The Conservatives are neoliberal fundamentalists, and they have supplanted collective, public values with individualistic, private values of market rationality. They have successfully displaced established models of welfare provision and state regulation through policies of privatisation and de-regulation and have shifted public focus, instigating various changes in subjectivity, by normalising individualistic self-interest, entrepreneurial values, and crass consumerism. And increasing the social and material exclusion of growing numbers living in absolute poverty.

Basically, the Tories tell lies to change perceptions, divert attention from the growing wealth inequality manufactured by their own policies, by creating scapegoats.

Another major assumption throughout the paper is that disabled people claiming ESA are somehow mistaken in assuming they cannot work: “how can we improve a welfare system that leaves 1.5 million people – over 60% of people claiming Employment and Support Allowance – with the impression they cannot work and without any regular access to employment support, even when many others with the same conditions are flourishing in the labour market? How can we build a system where the financial support received does not negatively impact access to support to find a job? How can we offer a better user experience, improve system efficiency in sharing data, and achieve closer alignment of assessments?”

The government’s brand of armchair pseudo-psychology, propped up by the Nudge Unit, is used to justify increasingly irrational requirements being embedded in policy. The government intend to merge health and employment services, redefining work as a clinical health outcome. According to the government, the “cure” for unemployment due to illness and disability and sickness absence from work, is… work.

The new work and health programme, “support” for disabled people, is actually just another workfare programme. We know that workfare tends to decrease the likelihood of people finding work.

Work is the only politically prescribed “route out of poverty” for disabled people, including those with mental distress and illness, regardless of whether or not they are actually well enough to work. In fact the government implicitly equates mental health with economic productivity. Work will set us free. Yet paradoxically, disabled people haven’t been and won’t be included in the same economic system which is responsible for their exclusion in the first place.

Competitive market economies exclude marginalised groups, that’s something we ought to have learned from the industrial capitalism of the last couple of centuries. GPs inform us that employers are not prepared to make the necessary inclusive workplace adjustments sick and disabled people often need to work.

But in a dystopic Orwellian world where medical sick notes have been politically redefined as ”fit notes”, sick and disabled people are no longer exempt from work, which is now held to be a magic “cure”. People are already being punished and coerced into taking any available job, regardless of its appropriateness, in an increasingly competitive and exclusive labor market.

The nitty gritty

You know the government are riding the fabled rubber bicycle when they calmly propose coercing the most disabled and ill citizens who are deemed unlikely to work by their doctors and the state (via the Work Capability Assessment) into performing mandatory work-related activities and finding jobs. Previously, only those assessed as possibly capable of some work in the future and placed in the Work Related Activity Group (WRAG) were expected to meet behavioural conditionality in return for their lifeline support.

However, the government have cut the WRAG component of Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) – another somewhat Orwellian name for a sickness and disability benefit – so that this group of people, previously considered to have additional needs because of their illness and disability, are no longer supported to meet the extra costs they face. The ESA WRAG rate of pay is now to be the same as Job Seeker’s Allowance.

If the government make work related activity mandatory for those people in the ESA Support Group, it will mean that very sick and disabled people will be sanctioned for being unable to comply and meet conditionality. This entails the loss of their lifeline support. The government have the cheek to claim that they will “protect and support” the most vulnerable citizens.

Hello, these ARE among our most vulnerable citizens. That’s why they were placed in the ESA support group in the first place.

Apparently, sick citizens are costing too much money. Our NHS is “overburdened” with ill people needing healthcare, our public services are “burdened” with people needing… public services. It is claimed that people are costing employers by taking time off work when they are ill. How very dare they.

Neoliberals argue that public services present moral hazards and perverse incentives. Providing lifeline support to meet basic survival requirements is seen as a barrier to the effort people put into searching for jobs. From this perspective, the social security system, which supports the inevitable casualties of neoliberal free markets, has somehow created those casualties. But we know that external, market competition-driven policies create a few “haves” and many “have-nots.” This is why the welfare state came into being, after all – because when we allow such competitive economic dogmas to manifest without restraint, we must also concede that there are always ”winners and losers.”

Neoliberal economies organise societies into hierarchies.The UK currently ranks highly among the most unequal countries in the world.

Inequality and poverty are central features of neoliberalism and the causes of these sociopolitical problems therefore cannot be located within individuals.

The ESA Support Group includes people who are terminally ill, and those with degenerative illnesses, as well as serious mental health problems. It’s suggested that treating this group of people with computer based Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (cCBT), and addressing obesity, alcohol and drug dependence will “help” them into work.

Ministers claim that this group merely have a “perception” that they can’t work, and that they have been “parked” on benefits. It is also implied that illness arises mostly because of lifestyle choices.

Proposals include a punitive approach to sick and disabled people needing support, whilst advocating financial rewards for employers and businesses who employ sick and disabled people.

And apparently qualified doctors, the public and our entire health and welfare systems have ingrained “wrong” ideas about sickness and disability, especially doctors, who the government feels should not be responsible for issuing the Conservatives recent Orwellian “fit notes” any more, since they haven’t “worked” as intended and made every single citizen economically productive from their sick beds.

So, a new “independent” assessment and private company will most likely soon have a lucrative role to get the government “the right results”.

Meanwhile health and social care is going to be linked with one main outcome: work. People too ill to work will be healthier if they… work. Our public services will cease to provide public services: health and social care professionals will simply become co-opted authoritarian ideologues.

Apparently, the new inequality and social injustice have nothing to do with an unequal distribution of wealth, resources, power and opportunities. Apparently our society is unequal only because some people “won’t” work. I’m just wondering about all those working poor people currently queuing up at the food bank, maybe their poorly paid, insecure employment and zero hour contracts don’t count as working.

I’ve written as I read this Orwellian masterpiece of thinly disguised contempt and prejudice. I don’t think I have ever read anything as utterly dangerous and irrational in all my time analysing Conservative public policy and the potential and actual consequences of them. These utterly deluded and sneering authors are governing our country, shaping our life experiences, and those of our children.

The sick role and any recovery time from illness or accident that you may need has been abolished. Work will cure you.

Well, at least until you die.

Pictures courtesy of Robert Livingstone

The closing date for the consultation is 17 February 2017.

You can download the full consultation document from this link.

You can take part in the consultation from this link.

I don’t make any money from my work. But you can support me by making a donation and help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to continue to provide support to others. The smallest amount is much appreciated – thank you.

Source:

Source: