Eugenics in a ball gown

I had a little discussion with Richard Murphy yesterday, and I mentioned that the right-wing libertarian think tank, the Adam Smith Institute, (ASI) has endorsed* the controversial work of Adam Perkins – “The Welfare Trait.” The ASI has been the impetus behind Conservative policy agendas and was the primary intellectual drive behind the privatisation of state-owned industries during the premiership of Margaret Thatcher, and alongside the Centre for Policy Studies and Institute of Economic Affairs, advanced a neoliberal approach towards public policy on privatisation, taxation, education, and healthcare, and have advocated the replacement of much of the welfare state by private insurance schemes.

(*The ASI review, written by Andrew Sabisky, was removed following wide criticism of Perkins’ methodology and other major flaws in his work. Consequently, the original hyperlink leads nowhere, so I’ve added an archived capture, to update.)

Professor Richard Murphy, a widely respected political economist and commentator, has written an excellent article: The Adam Smith Institute is now willing to argue that those on benefits are genetically different to the rest of us on the Tax Research UK site, which I urge you to read.

He says “What you see in this is the deliberate construction of an argument that those on benefits are genetically different from other people. The consequences that follow are inevitable and were all too apparent in the 1930s. And this comes from a UK think tank much beloved for Tory politicians.”

The Adam Smith Institute say this in their review of Adam Perkins’s book:

“With praiseworthy boldness, Perkins gets off the fence and recommends concrete policy solutions for the problems that he identifies, arguing that governments should try to adjust the generosity of welfare payments to the point where habitual claimants do not have greater fertility than those customarily employed. The book no doubt went to press before the Chancellor announced plans to limit child tax credits to a household’s first two children, but such a measure is very much in the spirit of this bullet-biting book. The explicit targeting of fertility as a goal of welfare policy, however, goes beyond current government policy. Perkins perhaps should also have argued for measures to boost the fertility of those with pro-social personalities, such as deregulation of the childcare and housing markets to cut the costs of sustainable family formation.”

And: “Over time, therefore, the work motivation of the general population is lowered. This occurs through both genetic and environmental channels. Personality traits are substantially heritable (meaning that a decent percentage of the variation in these traits is due to naturally occurring genetic variation). Given this fact, habitual welfare claimants with employment-resistant personalities are likely to have offspring with similar personalities.”

Personality disorder or simply maintaining the social order?

Two things concern me immediately. Firstly, there is no causal link established between welfare provision and “personality disorder” or “traits”, bearing in mind that the “employment-resistant personality” is an entirely made-up category and does not feature as a clinical classification in either the ICD-10 section on mental and behavioural disorders, or in the DSM-5. Nor is employment status currently part of any clinical diagnostic criteria. Personality disorders are defined by experiences and behaviours that differ from societal norms and expectations.

Personality disorder (and mental illness) categories are therefore culturally and historically relative. Diagnostic criteria and categories are always open to sociopolitical and economic definition, highly subjective judgments, and are particularly prone to political abuse.

“Drapetomania” for example, was a pseudoscientific definition of a mental illness that labelled slaves who fled captivity in the 1800s. Samuel A. Cartwright, who invented the category, also prescribed a remedy. He said: “with proper medical advice, strictly followed, this troublesome practice that many Negroes have of running away can be almost entirely prevented. In the case of slaves “sulky and dissatisfied without cause” – apparently a warning sign of their imminent flight – Cartwright prescribed “whipping the devil out of them” as a “preventative measure.” As a further “remedy” for this “disease”, doctors also made running a physical impossibility by prescribing the removal of both big toes. Such abusive application of psychiatry and the medicalisation of distress and rational responses to ethnic degradation and dehumanisation is part of the edifice of scientific racism.

The classification of homosexuality as a mental illness was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1974, and was replaced by the subsequent categories of “sexual orientation disturbance” and then “ego-dystonic homosexuality,” the latter was not deleted from the manual until 1987. Medicalising and stigmatising the experiences, behaviours and beliefs of marginalised social groups, and attempting to discredit and invalidate those group’s collective experiences is a key feature of political and cultural oppression.

Personality traits are notoriously difficult to measure reliably, and it is often far easier to agree on the behaviours that typify a disorder than on the reasons why they occur. As it is, there is debate as to whether or not personality disorders are an objective disorder, a clinical disease, or simply expressions of human distress and ways of coping. At the very least, there are implications regarding diagnoses that raise important questions about context, which include political and social issues such as inequality, poverty, class struggle, oppression, abuse, stigma, scapegoating and other structural impositions.

An over-reliance on a fixed set of behavioural indicators, some have argued, undermines validity, leaving personality disorder categories prone to “construct drift,” as the diagnostic criteria simply don’t provide adequate coverage of the construct they were designed to measure. There are no physical tests that can be carried out to diagnose someone with a personality disorder – there is no single, reliable diagnostic tool such as a blood test, brain scan or genetic test. Diagnosis depends on subjective judgment rather than objective measurement.

A diagnosis of personality disorder is potentially very damaging and creates further problems for individuals by undermining their sense of self, denying their identity, experience and locating the problems, regardless of their origin and who is responsible for them, in themselves. This is in addition to exposing people to stigma and discrimination, both within the mental health system, quite often, and more broadly within our society. Medicalising and stigmatising human distress permits society to look the other way, losing sight of an individual’s social needs, experiences and context. It also alienates the stigmatised individual, and enforces social conformity, compliance and cultural homogeneity.

It may be argued that the concept of personality disorder obscures wider social issues of neglect, poverty, inequality, power relationships, oppression and abuse by focusing on the labelling of the individual. Rather than being concerned with the impact and prevalence of these issues, public outrage is focussed on containing and controlling people who challenge normative consensus and who are perceived to be dangerous. Because there is no objective test to make a diagnosis, this makes the basis of such diagnosis very questionable and highlights the propensity for its political and punitive usage. The “diagnosis” of many political dissidents in the Soviet Union with “sluggish schizophrenia” who were subsequently subjected to inhumane “treatments” led to questions about such diagnoses and punitive regimes through stigma, labeling, dehumanisation, coercion and oppression, for example.

Secondly, to recommend such specific policies on the basis of this essentially eugenic argument betrays Perkins’s intention to provide a pseudoscientific prop for the libertarian paternalist (with the emphasis being on behaviourism) brand of neoliberalism and New Right antiwelfarism.

The taken-for-granted assumption that the work ethic and paid labor (regardless of its quality) may define a person’s worth is also very problematic, as it objectifies human subjects, reducing people to being little more than neoliberal commodities. Or a disposable reserve army of labor, at the mercy of “free market” requirements, if you prefer.

The government is currently at the centre of a United Nations inquiry into abuses of the human rights of ill and disabled people, and is also in breach of the rights of women and children, because of their anti-humanist, draconian welfare “reforms”. Human rights are the bedrock of democracy. The fact that some social groups are experiencing political discrimination and the failure of a government in a wealthy first-world liberal democracy to observe what are meant to be universal human rights ought to be cause for concern.

The rise of neoeugenics

Holocaust documentation has highlighted that the medicalisation of social problems and systematic euthanasia of people in German mental institutions in the 1930s provided the institutional, procedural, and doctrinal origins of the genocide of the 1940s. Eugenics in Germany was founded on notions of “scientific progress,” and was about ensuring mental, racial and genetic “hygiene” and “improving” the German race, which ultimately led to eliminativist attitudes towards politically defined “impure” others.

Eugenics is a theory of the possibility of improving the qualities of the human species or a particular population. It encourages the reproduction of persons with socially defined “desirable genetic qualities” and discourages the reproduction of persons with socially defined “undesirable genetic qualities.” Taken to its most extreme form, eugenics supports the extermination of some groups who some others consider to be “undesirable” population.

One example of eugenic policy is the recent limiting of tax credit support for children in poorer families to two children only. Iain Duncan Smith said that this is to encourage “behavioural change” to prevent poorer families having “too many” children.

Eugenics is widely considered as a movement that endorses human rights violations of some social groups. At the very least, eugenic policy entails violations of privacy, the right to found a family, the right to freedom from discrimination, the right to socioeconomic security and social protection, and at worst, violations of the right to life.

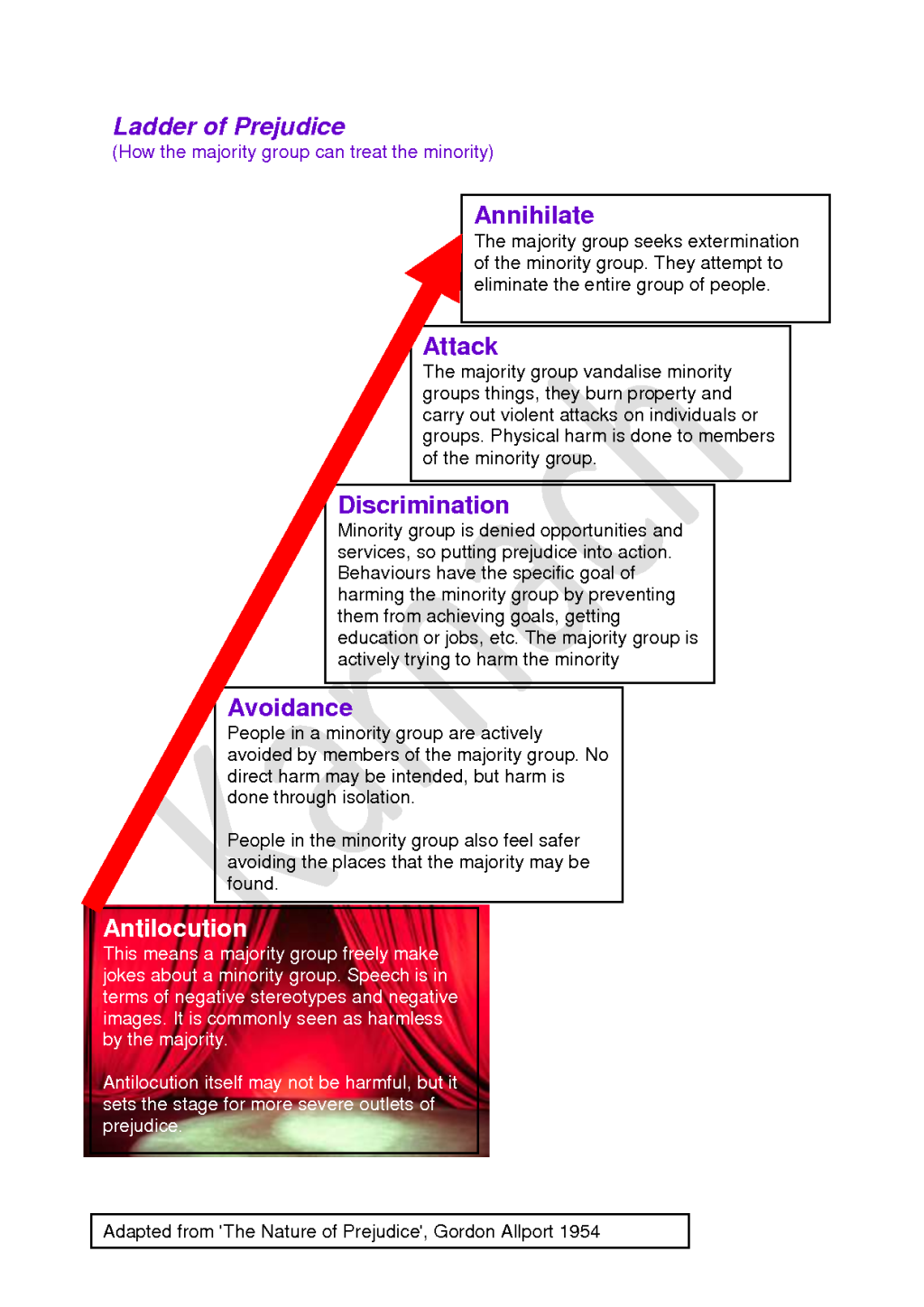

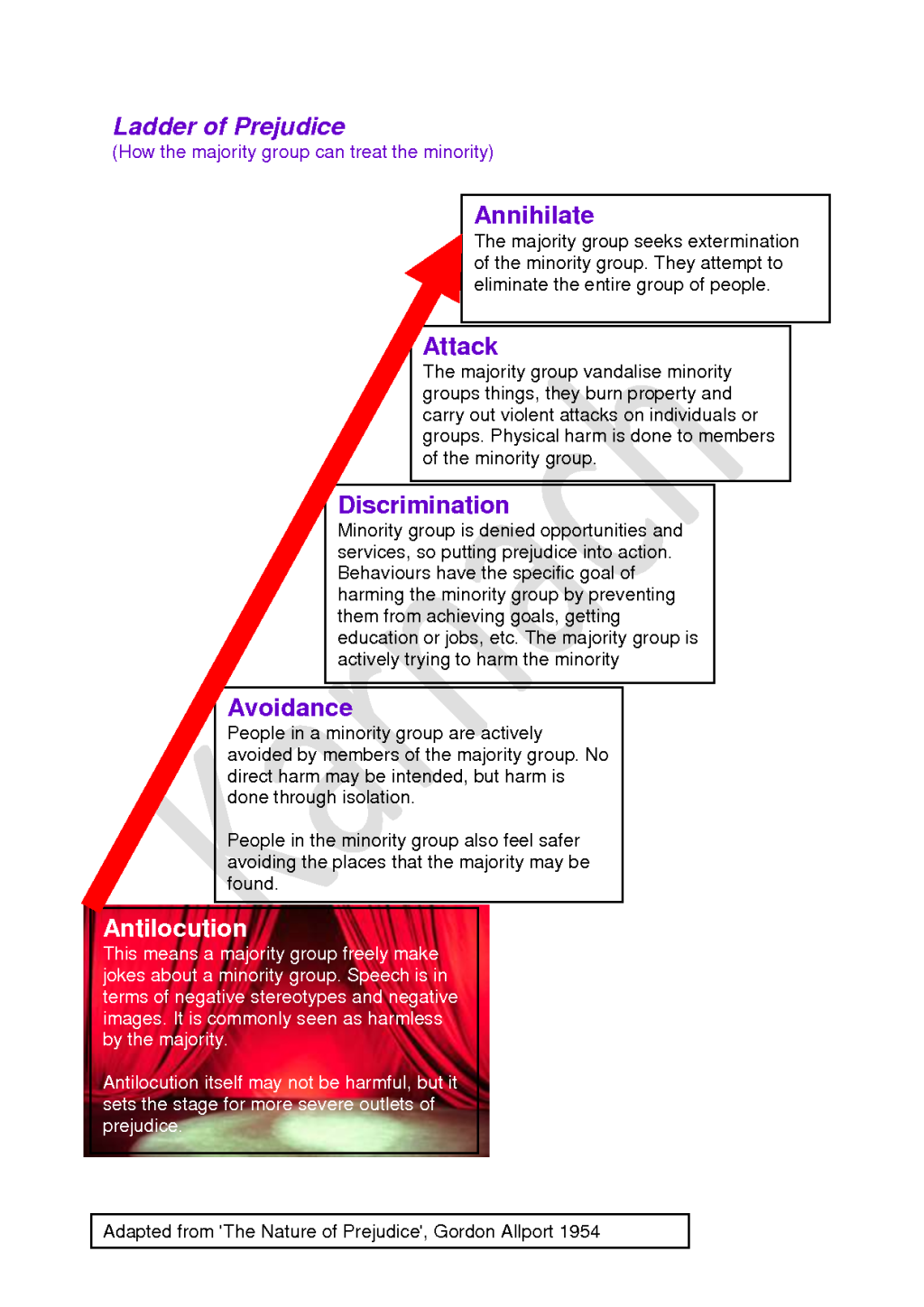

I have frequently referred to Gordon Allport in my writing. He was a social psychologist who studied the psychological and social processes that create a society’s progression from prejudice and discrimination to genocide. Allport’s important work reminds us of the lessons learned from politically-directed human atrocities and the parts of our collective history it seems we would prefer to forget.

In his research of how the Holocaust happened, Allport describes sociopolitical processes that foster increasing social prejudice and discrimination and he demonstrates how the unthinkable becomes tenable: it happens incrementally, because of a steady erosion of our moral and rational boundaries, and propaganda-driven changes in our attitudes towards politically defined others, all of which advances culturally, by almost inscrutable degrees.

The process always begins with political scapegoating of a social group and with ideologies that identify that group as “undesirable” and as the Other: an “enemy” or a social “burden” in some way. A history of devaluation of the group that becomes the target, authoritarian culture, and the passivity of internal and external witnesses (bystanders) all contribute to the probability that violence against that group will develop, and ultimately, if the process is allowed to continue evolving, extermination of the group being targeted.

Othering is recognised in social psychology as part of an outgrouping process that demarcates those that are thought to be different from oneself or the mainstream, most often using stigmatising to generate public moral outrage. It tends to reinforce and reproduce positions of domination and subordination. Othering historically draws on essentialising explanations, culturalist explanations, behavioural explanations, genetic explanations and racialising explanations.

Hate crime, eugenics and Allport’s ladder

In the UK, much of the media is certainly being used by the right-wing as an outlet for blatant political propaganda, and much of it is manifested as a pathological persuasion to hate others. We are bombarded with anti-muslim rhetoric, “poverty porn”, headlines that condemn people needing social security as “workshy” and “scroungers.” The political scapegoating narrative directed at ill and disabled people has resulted in a steep rise in hate crimes directed at that group. By 2012, hate crime incidents against disabled people had risen to record levels, and has continued to climb ever since, rising by a further 41% last year alone. We are certainly climbing Allport’s ladder of prejudice.

A freedom of information request to the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) discloses that between 2010 and 2015 the government closed 1,041,219 alleged cases of benefit fraud put forward by the public. Insufficient or no evidence of fraud was discovered in 887,468 of these. In 2015 alone, of the 153,038 cases closed by the DWP’s Fraud and Error Service, 132,772 led to no action. People can use an online form on the DWP website to anonymously report “suspects,” listing their eye colour, piercings, scars, tattoos and other details they deem relevant. Suspicions can also be logged through the DWP benefit fraud hotline.

The inaccurate reports throws into question multiple government advertising campaigns, claiming that the public has a “role” in identifying “benefit cheats”. Television adverts, social media posts, letters and radio campaigns have been used to warn claimants about fraudulently claiming benefits. Government statistics show fraudulent claims accounted for 0.7% – or £1.2bn – of total benefit expenditure in the financial year 2012-2013. Some of that figure may also contain a proportion of DWP errors. An estimated £1.6bn was underpaid to claimants by the DWP. Yet people’s neighbours are being encouraged to engage in a McCarthy-style reporting of suspected benefit fraud. And a significant proportion of the public are reporting innocent citizens.

There is considerable incongruence between cases of genuine fraud and public perception: an Ipsos Mori survey in 2013 found the public believed 24% of benefits were fraudulently claimed – 34 times greater than the level seen in official statistics.

The political construction of social problems also marks an era of increasing state control of citizens with behaviour modification techniques, (under the guise of paternalistic libertarianism) all of which are a part of the process of restricting access rights to welfare provision.

The mainstream media has been complicit in the process of constructing folk devils: establishing stigmatised, deviant welfare stereotypes and in engaging prejudice and generating moral outrage from the public:

“If working people ever get to discover where their tax money really ends up, at a time when they find it tough enough to feed their own families, let alone those of workshy scroungers, then that’ll be the end of the line for our welfare state gravy train.” James Delingpole 2014

Poverty cannot be explained away by reference to simple narratives of the workshy scrounger as Delingpole claims, no matter how much he would like to apply such simplistic, blunt, stigmatising, dehumanising labels that originated from the Nazis (see arbeitssheu.)

The Conservatives have strongly authoritarian tendencies, and that is most evident in their anti-democratic approach to policy, human rights, equality, social inclusion and processes of government accountability.

Conservative policies are entirely ideologically driven. It is a government that is manipulating public prejudice to justify massive socioeconomic inequalities and their own policies which are creating a steeply hierarchical society based on social Darwinist survival of the wealthiest “libertarian” principles. We have a government that frequently uses words like workshy to describe vulnerable social groups.

Conservative narrative and eugenics

This is a government intentionally scapegoating poor, unemployed, disabled people and migrants. A few years ago, a Tory councillor said that “the best thing for disabled children is the guillotine.” More recently, another Tory councillor called for the extermination of gypsies, more than one Tory (for example, Lord Freud, Philip Davies) have called for illegal and discriminatory levels of pay for disabled people, claiming that we are not worth a minimum wage to employers.

These weren’t “slips”, it’s patently clear that the Tories believe these comments are acceptable, and we need only look at the discriminatory nature of policies such as the legal aid bill, the wider welfare “reforms” and research the consequences of austerity for the poorest and the vulnerable – those with the “least broad shoulders” – to understand that these comments reflect how many Conservatives think.

Occasionally such narrative is misjudged, pushing a little too far against the boundaries of an established idiom of moral outrage, and so meets with public resistance. When this happens, it tends to expose the fault lines of political ideology and psychosocial manipulation, revealing the intentional political creation of folk devils and an extending climate of prejudice.

In Edgbaston, Keith Joseph, (1974) announced to the world that:

“The balance of our population, our human stock is threatened … a high and rising proportion of children are being born to mothers least fitted to bring children into the world and bring them up. They are born to mothers who were first pregnant in adolescence in social classes 4 and 5. Many of these girls are unmarried, many are deserted or divorced or soon will be. Some are of low intelligence, most of low educational attainment.”

And in 2010, the former deputy chairman of Conservative Party, Lord Howard Flight, told the London Evening Standard:

“We’re going to have a system where the middle classes are discouraged from breeding because it’s jolly expensive. But for those on benefits, there is every incentive. Well, that’s not very sensible.”

In 2013, Dominic Cummings, a senior adviser to the UK Secretary of State for Education, provoked a flurry of complaints about his eugenicist approach, claiming that “a child’s performance has more to do with genetic makeup than the standard of his or her education.”

Steven Rose, Emeritus Professor of Biology, offered a more detailed analysis in New Scientist, concluding:

“Whatever intelligence is, these failures show that to hunt for it in the genes is an endeavour driven more by ideological commitment than either biological or social scientific judgement. To suggest that identifying such genes will enable schools to develop personalised educational programmes to match them, as Cummings does, is sheer fantasy, perhaps masking a desire to return to the old days of the 11 plus. Heritability neither defines nor limits educability.”

Pseudoscience has long been used to attempt to define and explain social problems. Lysenkoism is an excellent example. (The term Lysenkoism is used metaphorically to describe the manipulation or distortion of the scientific process as a way to reach a predetermined conclusion as dictated by an ideological bias, most often related to political objectives. This criticism may apply equally to either ideologically-driven “nature” and “nurture” arguments.)

Eugenics uses the cover and credibility of science to blame the casualities of socioeconomic systems for their own problems and justify an existing social power and wealth hierarchy. It’s no coincidence that eugenicists and their wealthy supporters also share a mutual antipathy for political progressivism, trade unionism, collectivism, notions of altruism and of co-operation and class struggle.

It isn’t what it ought to be

Adam Perkins wrote a book that attempts to link neurobiology with psychiatry, personality and behavioural epigenetics, Lamarkian evolution, economics, politics and social policy. Having made an impulsive inferential leap across a number of chasmic logical gaps from neurobiology and evolution into the realms of social policy and political science, seemingly unfazed by disciplinary tensions between the natural and social sciences, particularly the considerable scope for paradigmatic incommensurability, he then made a highly politicised complaint that people are criticising his work on the grounds of his highly biased libertarian paternalist framework, highly partisan New Right social Conservatism and neoliberal antiwelfarist discourse.

The problem of discrete disciplinary discursive practices and idiomatic language habits, each presenting the problem of complex internal rules of interpretation, was seemingly sidestepped by Perkins, who transported himself across distinct spheres of meaning simply on leaps of semantic faith to doggedly pursue and reach his neuroliberal antiwelfarist destination. He seems to have missed the critical domain and central controversies of each discipline throughout his journey.

Perhaps he had a theory-laden spirit guide.

Einstein once famously said: “The theory tells you what you may observe.”

On reading Perkins’s central thesis, the is/ought distinction immediately came to mind: moral conclusions – statements of what “ought” to be – cannot be deduced from non-moral premises. In other words, just because someone claims to have knowledge of how the world is or how groups of people are – and how mice are, for that matter, since Perkins shows a tendency to conflate mice behaviour with human behaviour – (descriptive statements), this doesn’t automatically prove or demonstrate that he or she knows how the world ought to be (prescriptive statements).

There is a considerable logical gap between the unsupported claim that welfare is somehow “creating” some new kind of personality disorder, called “the employment-resistant personality”, and advocating the withdrawal of support calculated to meet only the basic physiological needs of individuals – social security benefits only cover the costs of food, fuel and shelter.

While Perkins’s book conveniently fits with Conservative small state ideology, behaviourist narratives, and “culture of dependency” rhetoric, there has never been evidence to support any of the claims that the welfare state creates social problems or psychological pathologies. Historically, such claims tend to reflect partisan interests and establish dominant moral agendas aimed at culturally isolating social groups, discrediting and spoiling their identities, micromanaging dissent, and then such discourses are used in simply justifying crass inequalities and hierarchies of human worth that have been politically defined and established.

It’s truly remarkable that whenever we have a Conservative government, we suddenly witness media coverage of an unprecedented rise in the numbers of poor people who have suddenly seemingly developed a considerable range of personal “ineptitudes” and character “flaws.” Under the Thatcher administration, we witnessed Charles Murray’s discredited pseudoscientific account of “bad” and “good” folk-types taking shape in discriminatory policy and prejudiced political rhetoric.

Social Darwinism has always placed different classes and races in hierarchies and arrayed them in terms of socially constructed notions of “inferiority” and “superiority.” Charles Murray’s controversial work The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life presents another example of a discredited right-wing ideological architect, funded by the right-wing, who was then used to prop up an authoritarian Conservative antiwelfarist dogma that was also paraded as “science.” Murray had considerable influence on the New Right Thatcher and Reagan governments. Critics were often dismissed, on the basis that they were identified with “censorious political correctness,” which of course was simply a right-wing attempt to close down genuine debate and stifle criticism. The Bell Curve was part of a wider campaign to justify inequality, racism, sexism, and provided a key theme in Conservative arguments for antiwelfarism and anti-immigration policies.

A recent comprehensive international study of social safety nets from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard economists refutes the Conservative “scrounger” stereotype and dependency rhetoric. Abhijit Banerjee, Rema Hanna, Gabriel Kreindler, and Benjamin Olken re-analyzed data from seven randomized experiments evaluating cash programs in poor countries and found “no systematic evidence that cash transfer programs discourage work.”

The phrase “welfare dependency” was designed to intentionally divert attention from political prejudice, discrimation via policies and to disperse public sympathies towards the poorest citizens. It is used to justify inequality.

Adam Perkins does nothing to consider, isolate and explore confounding variables regarding the behaviours and responses of people needing social security support. He claims our current level of support is too high. I beg to differ. Empirical evidence clearly indicates it is set much too low to meet people’s physiological needs fully. Poverty affects people’s mental health as well as their physical health. There is a weight of empirical evidence confirming that food deprivation and income insecurity is profoundly psychologically harmful as much as it is physiologically damaging. (See the Minnesota semistarvation experiment, for example.) Describing people’s anger, despondency and distress at their circumstances as “antisocial” is profoundly oppressive. The draconian policies that contribute to creating those circumstances are antisocial, not the people impacted by those policies.

If people can’t meet their basic survival needs, it is extremely unlikely that they will either have the capability or motivation to meet higher level psychosocial needs, including social obligations and responsibilities to find work and meet increasingly Kafkaesque welfare conditionality requirements.

However, people claiming social security support have worked and contributed to society. Most, according to research, are desperate to find work. Most do. It is not the same people year in year out that claim support. There is no discrete class of economic freeriders and “tax payers.” The new and harsh welfare conditionality regime tends to push people into insecure, low paid employment, which establishes a revolving door of work and welfare through no fault of those caught up in it.

There is a clear relationship between human needs, human rights, and social justice. Needs are an important concept that guide empowerment based practices and the concept is intrinsic to social justice. Furthermore, the meeting of physiological and safety needs of citizens ought to be the very foundation of economic justice as well as the development of a democratic society.

The Conservatives (and Perkins) claim that the social security system, which supports the casualties of neoliberal free markets, have somehow created those casualties. But we know that the competitive, market choice-driven Tory policies create a few haves and many have-nots.

As I’ve pointed out many times before, such political rhetoric is designed to have us believe there would be no poor if the welfare state didn’t “create” them. But if Conservatives must insist on peddling the myth of meritocracy, then surely they must also concede that whilst such a system has some beneficiaries, it also creates situations of insolvency and poverty for others.

Inequality is a fundamental element of the same meritocracy script that neoliberals so often pull from the top pockets of their bespoke suits. It’s the big contradiction in the smug meritocrat’s competitive individualism narrative. This is why the welfare state came into being, after all – because when we allow such competitive economic dogmas to manifest without restraint, there are always winners and losers. Inequality is a central feature of neoliberalism and social Conservatism, and its cause therefore cannot be located within individuals.

It’s hardly “fair”, therefore, to leave the casualties of competition facing destitution and starvation, with a hefty, cruel and patronising barrage of calculated psychopolicical scapegoating, politically-directed cultural blamestorming, and a coercive, punitive behaviourist approach to the casualities of inbuilt, systemic, inevitable and pre-designated sentences of economic exclusion and poverty.

That would be regressive, uncivilised, profoundly antidemocratic and tyrannical.

This work was cited and referenced in Challenging the politics of early intervention: Who’s ‘saving’ children and why, by Val Gillies and Rosalind Edwards, here.

—

My work is unfunded and I don’t make any money from it. But you can support Politics and Insights and contribute by making a donation which will help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others.

Young Bullers

Young Bullers