Today, while everyone is being distracted by the continuing resignations from Theresa May’s disintegrating government, the Conservatives are openly talking among themselves (again) about charging for NHS services. So much for the government’s continued reassurances and promises about UK healthcare continuing to remain ‘free at the point of access.’

The NHS has never been safe in Conservatives hands.

Last week I wrote an article about the stealthy creep of rationing of treatments in the NHS, and how gatekeeping has become a watchword within our public services over the past seven years. It’s being driven by the government’s deep affection for neoliberal dogma, the drive for never-ending ‘efficiency savings’ and the Conservatives’ lean, mean austerity machine. Perish the thought that the public may actually need to use the public services that they have funded through their contributions to the Treasury, in good faith.

One important point I didn’t raise in the article was about how the marketisation of the NHS has given rise to ‘perverse incentives’, which violate the very principles on which the national health service was founded. Neoliberal policies have shifted priorities to developing profitable ‘care markets’ making ‘efficiency’ savings and containing costs, rather than delivering universal health care.

Another shift in emphasis is the “behavioural turn”. It’s politically convenient to claim that people’s behaviours are a major determinant of their health. Some illnesses are undoubtedly related to lifestyle – type two diabetes, for example. But it is difficult to blame individual’s behaviours for type one diabetes, which is an autoimmune disease, and these may happen to people who lead very healthy lifestyles, as well as those who don’t. This ‘behavioural turn’ shifts emphasis from the impact of structural conditions – such as rising inequality and poverty – on public health. It also provides a political justification narrative for cuts to healthcare and welfare provision. (See also The NHS is to hire 300 employment coaches to find patients jobs to “keep them out of hospital”. )

Behavioural economists have claimed that ‘nudge’ presents an effective way to ‘change behaviours’ within the NHS and ‘improve outcomes’ at lower cost than traditional policy tools. Back in 2015, the Nudge Unit were looking for “many potentially fruitful areas in which to use behavioural insight to improve health and health-service efficiency, either by retrofitting existing processes or by designing completely new services most effectively.” ‘Fruitful’ as in lucrative for the part-privatised company, but not so lucrative for the NHS.

Behavioural economists are working for the government and public sector to “harness [public] behaviours to shift and reduce patterns of demand in many public services.” The problem is that human needs arising from illness are not quite the same thing as human behaviours and roles, yet the government are increasingly conflating the two. (See discussion on Talcott Parsons and the ‘sick role’ in this article, for example, along with that on ‘work is a health outcome’.)

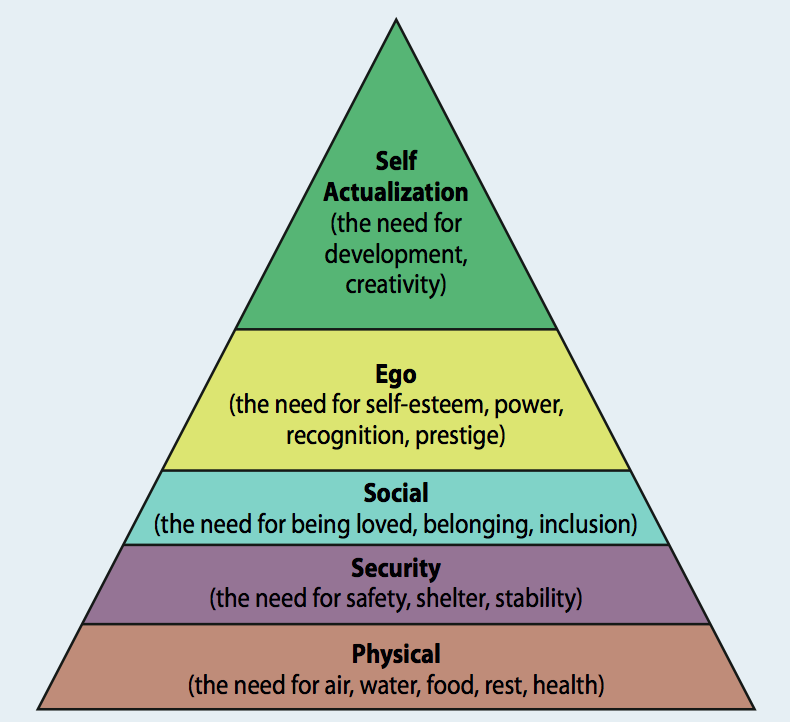

Public services are associated with fundamental human rights, which in turn are based on notions of fundamental human need. Addressing basic human needs is fundamental to survival.

As Abraham Maslow concluded, motivation for behaviours is is closely related to fulfilling our basic needs, because if they are not met, then people will simply strive to make up the deficit as a priority. This undermines aspiration and human potential. Fulfilment of psychosocial needs will become a motive for behaviour only as long as basic physiological needs ‘below’ it have been satisfied. Health is a fundamental human need. To paraphrase Maslow, we don’t live by bread alone, unless there is no bread.

Public services are an essential part of developed democracies, they ensure all citizens can meet their basic needs, and therefore, the provision promotes wider social and economic wellbeing and progress.

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs

The Nudge Unit had already run a trial in Nottingham, which provided feedback to doctors of the cost of a commonly used discretionary lab test. This prompt retained clinical freedom, and did not ask doctors to order fewer tests – but the number of

tests fell by a third.

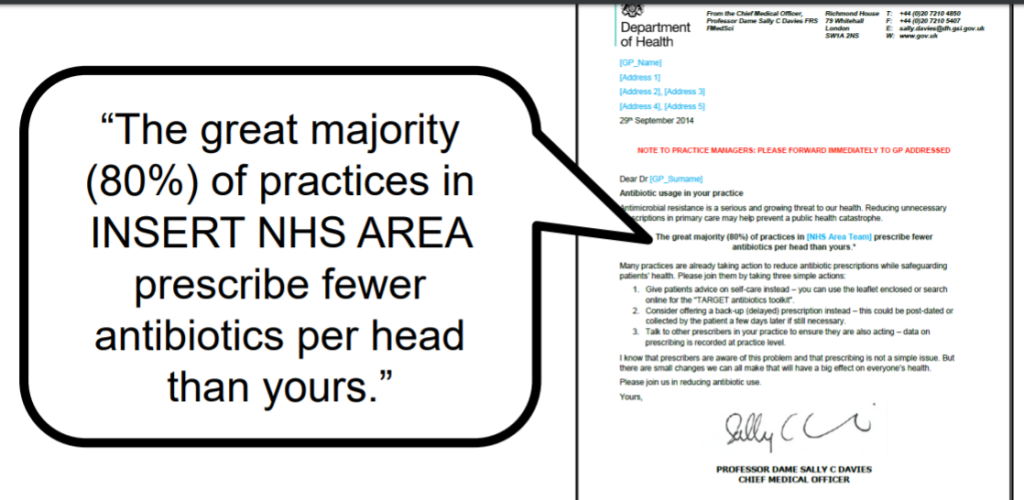

In 2016 the UK government set a target to half ‘inappropriate’ antibiotic prescribing by 2020. The Nudge Unit set out to “improve prescribing in line with government ambitions”.

Behavioural economists from the Unit claimed that by informing doctors that they are prescribing more antibiotics relative to 80 per cent of their peers, they are reducing the number of ‘unnecessary’ prescriptions by 3.3 per cent (more than 73,000 prescriptions) – helping to address what the Chief Medical Officer has identified as perhaps the greatest medical threat of our age – antibiotic resistance.

Between 2014 and 2015, the Behavioural Insights Team sent letters to 800 GP practices, telling them that other practices were recommending the use of antibiotics in fewer cases. (There is no evidence presented to determine if this was actually true, and judging by the template letter, it’s highly unlikely that it was true.)

The nudge method employed is called ‘social norming’, which operate as a kind of community enforcement, as norms are unwritten rules that define ‘appropriate’ behaviours for social groups. We tend to conform to the expectations of others. Changing perceptions of norms alters people’s expectations and behaviour.

Understanding norms provides a key to understanding social influence in general and conformity in particular. The Conservatives have traditionally placed a significant emphasis on social conformity.

There are ‘hotspots’ where more antibiotics are prescribed. However, the fact that these places tend to be some of the most deprived areas of the country strongly hints that there are underlying socioeconomic factors at play that cannot be solved with a nudge or prod. Research indicates that community socioeconomic variables may play a significant role in sepsis-attributable mortality, for example.

Social problems such as poverty and inequalities in health arise because of unequal distributions of wealth and power, therefore these problems require solutions involving addressing socioeconomic inequality. As it is, the government is unprepared to spend public funds on public services to redistribute resources.

The behavioural study did not include any consideration of socioeconomic variables on rates or severity of infection, or types of infection.

The idea that ‘changing the prescribing habits in hospitals’ and GP surgeries will impact on antibiotic resistance is based on an assumption that doctors over prescribe antibiotics in the first place. There is no evidence that this is the case, and it’s very worrying that anyone would think that targeting doctors with behaviourally-based remedies will address antibiotic resistance and assure us, at the same time, that antibiotics are actually prescribed when appropriate, and tailored, ensuring the safety and wellbeing of the patient, rather than being prescribed according to arbitrary percentage norms distributed by behavioural economists.

The trials did not include sufficient data regarding clinical detail or diagnostic uncertainty that might justify antibiotic prescribing in individual cases.

One of the nudge unit team’s key aims is to design policies which reduce costs. They say: “The solution to the problem of AMR is not just to produce new and better drugs – that takes time, and a great deal of money. We must also reduce our use of antibiotics when they are not needed. Sadly, it seems that they are used unnecessarily twenty percent of the time in the UK”.

The various Nudge Unit reports on behavioural strategies that target doctors don’t mention any follow-up research to ensure that the reduction in antibiotic prescriptions did not correlate with an increase in the severity of infections or poor outcomes for patients. In fact one report highlighted that those who were admitted to hospital because their condition deteriorated were excluded from the trial, as they no longer met the inclusion criteria. That effectively means that any adverse consequences for patients who were not given antibiotic treatment was not reported. And that matters.

The authors say “We as the authors debated at length as to whether we should emphasise the fact that 80% of the prescriptions are being used in necessary cases.”

There is no indication of how ‘necessary cases’ are determined, and more to the point, who determines what is a ‘necessary case’ for antibiotic treatment. Furthermore, the report uses some troubling language, for example, doctors prescribing antibiotics ‘above average’ were referred to more than once as the “worst offenders.” However, as I’ve already touched on, patients needs may well vary depending on a range of variables, such as the socioeconomic conditions of their community, and of course, complex individual comorbidities, which may not be mentioned in full when doctors write up the account for the prescription.

Sepsis, which may arise from any kind of infection is notoriously difficult to diagnose. It is insidious and can advance very rapidly. It’s even more difficult to determine when a patient has other conditions. For example, sepsis can arise when someone has flu. That happened to me, when I had developed pneumonia without realising that I had. It’s standard practice for paramedics to administer a broad spectrum antibiotic and intravenous fluids to treat suspected sepsis and septic shock. This can often save lives. Sepsis kills and disables millions and requires early suspicion and antibiotic treatment for survival.

Once the causative agent for the infection is found, the IV antibiotics may then be tailored to treat it. The wait without any treatment until a firm diagnosis is potentially life-threatening. But the biochemical tests, such as CRP, and X-rays take time.

Treatment guidelines call for the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics within the first hour following suspicion of septic shock. Prompt antimicrobial therapy is important, as risk of dying increases by approximately 10% for every hour of delay in receiving antibiotics. This time constraint does not allow the culture, identification, and testing for antibiotic sensitivity of the specific microorganism responsible for the infection. Therefore, combination antimicrobial therapy, which covers a wide range of potential causative organisms, is tied to better ‘outcomes’.

In the trial, behavioural economists referred to medical notes, and if there is no diagnosis, the necessity of the prescription is then questioned. Knowledge of complex medical histories may also influence doctors’ decisions, and this may not have been mentioned on medical record. A cough and breathlessness is a common symptom influenza. However, a patient with a condition that compromises their immunity, or someone who needs immune suppressants, for example, is rather more at risk of developing bacterial pneumonia than others, and someone with COPD or asthma is also at increased risk.

If a person dies because treatment was not given promptly in high suspicion cases of severe infection and sepsis, who is to be held accountable, especially in a political context where treatments are being rationed and prescriptions are being increasingly policed?

It’s also worth bearing in mind that massive doses of antibiotics are added to livestock feed as a preventative measure and to promote growth before the animals are slaughtered and enter the food chain. Using antibiotics during the production of meat has been heavily criticised by physicians and scientists, as well as animal activists. The pharmaceutical industry is making billions annually from antibiotics fed to livestock, which highlights the perverse incentives of the profit motive and potentially catastrophic impact on humans. It is estimated that between 70 – 80 percent of the total of antibiotics used around the world are used within the animal farming and food industry. No-one is nudging the culprits.

The potential threat to human health resulting from inappropriate, profit seeking antibiotic use in food animals is significant, as pathogenic-resistant organisms propagated in these livestock are poised to enter the food supply and could be widely disseminated in food products.

Antibiotics used on farms can spill over into the surrounding environment, for instance through water run-off and slurry, according to a report from the UN’s environment body, last year, with the potential to create resistance to the drugs across a wide area.

In 2013, researchers showed that people who simply lived near pig farms or crop fields fertilized with pig manure are 30% more likely to become infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria.

Cash for care – rationing referrals to hospital consultants and diagnostic testing

It was announced in April this year that General Practitioners (GPs) across England will be able to “better manage” hospital referrals with a “digital traffic light system” developed by the Downing Street policy wonks. This nudge is designed to target the ‘referral behaviours’ of GPs.

GPs are being offered cash payments as an ‘incentive’ to not refer patients to hospitals – including cancer patients – according to an investigation by Pulse, a website for GPs.

Furthermore, a leaked letter sent by NHS to England to Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and seen by Pulse magazine last year, asks that all family doctors in England to seek approval from a medical panel for all non-urgent hospital referrals.

A “clinical peer review of all referrals from general practice by September 2017”, will be required, the letter said.

To ‘incentivise’ the scheme, the letter said that there will be “significant additional funding” for commissioners that establish peer-led policing schemes. It added that it could reduce hospital referral rates by up to by 30 per cent. NHS England said that they want to introduce the “peer review scheme” whereby GPs check the referrals of one another to ensure they are ‘appropriate’. However, experts warn this increasingly Kafkaesque layer of bureaucracy could lead to more problems and possible conflict with patients’ safety and standard of care.

In a trial of the nudge scheme, four NHS clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) have been using “profit share” initiatives to ration care, to help them ‘operate within their budgets’. Clinical Commissioning Groups hold the budget for the NHS locally and decide which services are provided for patients.

Through this scheme, GPs are told they will receive up to half of the money that is saved by fewer patients going to hospitals for tests and treatments.

So to clarify, surgeries are being offered financial ‘incentives’ for not sending patients to hospital to save money, that is then reinvested in part to implement further rationing of healthcare. The move has been widely condemned as a “dereliction of duty” by the community of medical experts and professionals. Referrals to consultants often involve important diagnostic procedures, therefore there is often no way of knowing for sure in advance of the referral whether or not it is “warranted”.

The NHS has had ‘referral management centres’ in place for many years. However, last year they were at the epicentre of a scandal when it was revealed that the use of these centres has increased 10-fold over recent years. Furthermore, the centres are privately run and extremely expensive to employ, diverting funds that could simply be spent on patient care.

Moreover, those who were reviewing the referrals were also found to have varying levels of clinical knowledge, and so were not always able to correctly identify which referrals were ‘necessary’. They were also extremely inefficient as patients were forced to wait a long time for appointments.

The Pulse investigation into referral incentive schemes being run by NHS clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) across England found some regions offering GPs as much as 50 per cent of any savings they can make. The “profit-share” arrangements mean practices stand to benefit financially by not sending patients for treatment or to see a specialist.

Hospitals are paid for operations and other activity, so by sending patients to cheaper services run by GP practices – such as diabetes and pulmonary clinics – or by keeping them out of hospital altogether, practices can increase the size of savings. GPs are not paid per procedure. Rather, they receive a single payment when each patient is registered with them.

Currently, when doctors are referring patients for appointments with hospital consultants, the nudge – in the form of a “Capacity Alert System” – operates by displaying a red light next to hospitals with lengthy waiting times, and a green light next to those with more availability, on the system.

The system underwent two trials in north-east and south-west London over the winter. During these pilots the number of referrals made to overburdened hospitals was reduced by 40%, while those made to hospitals with ‘spare capacity’ rose by 14%, according to NHS England. There was no comment made regarding the impacts of the scheme on patients’ health.

GP leaders have also said it is “insulting” to suggest doctors are sending patients to hospital arbitrarily, and raise significant conflicts of interest.

“Cash incentives based on how many referrals GPs make have no place in the NHS, and frankly, it is insulting to suggest otherwise,” said Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard, chair of the Royal College of GPs.

“Of course, it’s important to take measures to ensure that GP referrals are appropriate and high-quality, but payments to reduce referrals would fly in the face of this, and erode the trust our patients have in us to do what is best for them and their health.”

The NHS has been squeezed for increasingly drastic ‘efficiency savings’ in the past eight years. It’s absurd, however, that a huge amount of money is being spent on restricting access to healthcare, rather than on simply adequately funding healthcare provision.

Dr Peter Swinyard, chair of the Family Doctor Association, said the profit-share schemes were “bizarre”, adding: “From a patient perspective, it means GPs are paid to not look after them.

“It’s a serious dereliction of duty, influenced by CCGs trying to balance their books.”

Meanwhile, NHS Barnsley CCG has identified a £1.4m funding pot to pay its practices if they achieve a reduction in referrals to specialties, including cardiology, pancreatic surgery, and trauma and orthopaedics.

The CCG said the 10 per cent target was “ambitious but achievable”.

Last year it was discovered that the NHS has to spend £1.5 billion in legal costs when patients don’t get what the standard of care expected and pay for from their healthcare providers. In 2015/16, there was a 27% increase in the number of claims and a 72% increase in legal cost, which amounted to £1.5 billion. With the amount of money that the NHS is spending on legal costs for medical blunders, the NHS could have paid for the training of more than 6,000 doctors. Or eased the rationing of essential healthcare provision.

The purpose of the NHS has been grotesquely distorted: it was never intended to be a bureaucratic gatekeeping exercise that rations healthcare. The purpose of all public services is to provide a public service, not ration provision. Such is the irrationality of the government’s ‘market place’ and ‘profit over human need’ narrative.

Dr Eric Watts, a consultant haematologist for the NHS, says that the British government couldn’t care less about the fall of the NHS. He said, “This is a triumph of secrecy and implacable lack of care about the NHS by a Government determined to watch it fail then fall.”

One CCG told Pulse: “Ensuring treatment is based on the best clinical evidence and improving historical variation in access is essential for us locally.

“Financially, it is an effective use of local resources which will improve patient experience and outcomes and increase investment in primary care in line with the Five Year Forward View commitments.” Those ‘commitments’ are the increasing implementation of cuts to healthcare provision and funding.

Cuts to care may well improve financial ‘management’ but it cannot be claimed that healthcare rationing “improves health outcomes” for patients. That flies in the face of rationality.

NHS England also said last year that funding will be available for CCGs to start “peer review schemes”, where GPs police each other – checking that their colleagues are referring ‘appropriately’, but it is not clear what it thinks about direct payments linked to cutting referrals.

The “Cash for Cuts” investigation, by GP publication Pulse, asked all 207 CCGs in England about their processes for cutting referrals. Of the 180 who responded, 24 per cent had some kind of incentive scheme aimed at lowering the numbers of referrals.

This included payments for getting GPs to “peer review” each other’s referrals or other strategies.

Dr Chaand Nagpaul, from the British Medical Association (BMA) has also criticised the nudge scheme. He says “It’s a blunt instrument which is not sensitive to the needs of the patient and is delaying patient care.

“It has become totally mechanistic. It’s either administrative or not necessary for the patient. It’s completely unacceptable. Performance seems to be related to blocking referrals rather than patient care.”

The CCGs have defended the schemes, saying that at the time they were pushed through, the NHS was struggling through the worst winter ever in its history and had not been able to hit target waiting times since 2015. The CCGs have said that the scheme is only to help reducing ‘unnecessary referrals’ and therefore improve outcomes for ‘genuine patients’, and not to reduce numbers overall. Who decides which patients are ‘genuine’, and on what criteria?

Dr Dean Eggitt, who is the British Medical Association’s GP representative for Barnsley, Doncaster, Rotherham and Sheffield, also disagrees with the scheme.

“The scheme is unsafe and needs to be reviewed urgently,” he said.

The BMA’s GP committee have said that it had raised concerns nationally where CCGs have set an “arbitrary target” for reducing referrals.

Before Christmas, Jeremy Hunt, the Health Secretary, announced that he wanted hospitals to find another £300m in savings on basic items like surgical gloves and bandages, and a long-awaited pay rise for nurses is contingent on staff boosting “productivity”.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: “Patients must never have their access to necessary care restricted – we would expect local clinical commissioning groups and NHS England to intervene immediately if this were the case.”

I’ve asked NHS England whether it would be reviewing cases where GPs stand to profit financially for not referring patients, along with others, but I have had no response at time of this publication.

The NHS was founded on the principle of free and open access to healthcare provision for everyone. The nudge schemes I’ve outlined have introduced ‘perverse incentives’ that prompt GPs to ration health care. I have argued elsewhere on many occasions that nudge and the discipline of behavioural economics more generally is technocratic prop for a failing political and socioeconomic system of organisation – neoliberalism. Rather than review the failures of increasing privatisation and ‘competition’, the government chose to deny them, applying increasingly irrational ‘solutions’ to the logical gaps in their ‘marketplace’ dogma.

Yet it is blindingly clear that citizens needs and their human rights are being increasingly sidestepped by the absolute prioritisation of the private profit incentive.

Nudge isn’t about ‘economics theory and practice adapting to human decision making’, as is widely claimed. It isn’t about remedying ‘cognitive biases’. It isn’t about people making ‘flawed decisions’.

It’s about holding citizens responsible for the problems created by a flawed socioeconomic model. It’s about a limited view of human behaviours and potential, because it frames the poorest citizens in an increasingly unequal society as ‘failed entrepreneurs’. Those members of the public who need to access public services are increasingly being portrayed as an economic ‘burden’. As such, nudge places limitations on and replaces genuine problem-solving approaches to public policy.

Nudge is about authoritarian governments using a technocratic prop to adapt human perceptions, behaviours and expectations, aligning them to accommodate inevitable catastrophic social outcomes. These outcomes are symptomatic of the failings and lack of rational insights of wealthy and powerful neoliberal ideologues, who are determined to dismantle our public services. Without the consent of the majority of citizens.

The NHS was never safe in his hands. The company he keeps has made sure of that.

I don’t make any money from my work. But if you like, you can support Politics and Insights and contribute by making a donation which will help me continue to research and write informative, insightful and independent articles, and to provide support to others who are vulnerable because of the impacts of government policies. The smallest amount is much appreciated, and helps to keep my articles free and accessible to all – thank you.