Background

Last April, more than 400 psychologists, counsellors and academics signed an open letter condemning the profoundly disturbing psychological implications of the government’s austerity and welfare reform measures. The group of professionals said that over the past five years the types of issues causing clients distress had shifted dramatically and now include increasing inequality, outright poverty and that people needing support because of structural problems, such as benefits claimants, are being subjected to a “new, intimidatory kind of disciplinary regime”.

The signatories of the letter, published in The Guardian, express concern over chancellor George Osborne’s plans, laid out in the latest budget, to embed psychological therapy in a coercive back-to-work agenda. Osborne said the government will aim to give online CBT to 40,000 recipients of Jobseeker’s Allowance, Employment and Support Allowance, people on the Fit for Work programme, as well as putting therapists in more than 350 job centres.

The letter stated that the government’s proposed policy of linking social security benefits to the receipt of “state therapy” is utterly unacceptable. The measure, casually described as “get to work therapy,” was discussed by George Osborne during his last budget.

The letter’s signatories, all of whom are experts in the field of mental health, have said such a measure is counter-productive, “anti-therapeutic,” damaging and professionally unethical. The intimidatory disciplinary regime facing benefits claimants would be made even worse by further unacceptable proposals outlined in the budget.

I raised my own concerns about Osborne’s proposals in March last year. Amongst the groups represented by the signatories were Psychologists Against Austerity, Britain’s Alliance for Counselling and Psychotherapy, Psychotherapists and Counsellors for Social Responsibility, the Journal of Public Mental Health, and a range of academic institutions including Goldsmiths, Birkbeck, the University of London, the University of Amsterdam, Manchester Metropolitan University and the University of Brighton.

The proposals are widely held to be profoundly anti-therapeutic, potentially very damaging and professionally unethical. With such a narrow objective, the delivery will invariably be driven by an ideological agenda, politically motivated outcomes and meeting limited targets, rather than being focused on the wellbeing of individuals who need support and who may be vulnerable.

A major concern that many of us have raised is regarding consent to participation, as, if benefit conditionality is attached to what ought to be a voluntary engagement, that undermines the fundamental principles of the right to physical and mental care. Such an approach would reduce psychologists to simply acting as agents of state control, enforcing compliance and conformity. That is not therapy: it’s psychopolitics and policy-making founded on a blunt behaviourism, which is pro-status quo, imbued with Conservative values and prejudices. It’s an approach that does nothing whatsoever to improve public life or meet people’s needs.

The highly controversial security company G4S are currently advertising for Cognitive Behavioural Therapists to deliver “return-to-work” advise in Surrey, Sussex and Kent.

The Role Description:

- Manage a caseload of Customers and provide return-to-work advice and guidance regarding health issues.

- Targeted on the level, number and effectiveness of interventions in re-engaging Customers and Customer progression into work.

- Focus on practical techniques that enable them to manage their conditions to enter and sustain employment.

- Work with Customers on a one-to-one basis and in groups to provide support on a range of mental health conditions. Refer clients to relevant external health or specialist services as required

- Conduct bio-psychosocial assessments via face-to-face and telephone-based interventions and produce tailored action plans to support Customers in line with contractual MSO.

- Deliver specific health for employment workshops and input into delivery models to support achievement of MSO

- Build relationships with key stakeholders including GP’s, employers and relevant NHS bodies

- Identify and build relationships with other organisations that contribute to the successful delivery of the programme.

- Expected to contribute substantially to the development of the service. Including the routine collection, review and feedback of activity/data, ensuring that activity targets are adhered to.

Basic Requirements

- Experience of delivering CBT.

- Evidence of understanding of Welfare to Work and the issues that unemployed people face.

This is yet another lucrative opportunity for private companies to radically reduce essential provision for those that really need support, nonetheless, costing the public purse far more to administer than such an arrangement could possibly save, despite the government’s dogged determination to rip every single penny from sick and disabled people and drive them into low paid, insecure jobs.

G4S priorities and the ideological context

“We are saving the taxpayer £120 million a year in benefit savings.” Sean Williams – Welfare to Work, Managing Director, G4S.

Welfare to work schemes exploit unemployed people desperately seeking work. Work programmes are mandatory, if people refuse to participate, they face sanctions, entailing the withdrawal of their lifeline benefit, which was originally calculated to meet basic physiological needs only. Workfare is unpaid labour provided as a handout to business, tax payers are subsidising the wage bill of the private sector. Workfare also serves to drive wages down, it is a disincentive for employers to create jobs that pay a fair wage.

Anti-workfare group Boycott Workfare say that workfare replaces jobs and undermines working conditions and wages. A research report in 2012 found a Work Programme success rate of just 2.3%. Given that 5% of people who are unemployed in the long term would be expected to find employment if left to their own devices, the Work Programme is considered less successful than leaving people to make their own choices regarding their own work experiences.

Work as a “health” outcome

The Conservatives have come dangerously close to redefining unemployment as a psychological disorder, and employment is being redefined as a “health outcome.” The government’s Work and Health programme involves a plan to integrate health and employment services, aligning the outcome frameworks of health services, Improving Access To Psychological Therapies (IAPT), Jobcentre Plus and the Work Programme.

But the government’s aim to prompt public services to “speak with one voice” is founded on questionable ethics. This proposed multi-agency approach is reductive, rather than being about formulating expansive, coherent, comprehensive and importantly, responsive provision.

Psychopolitics is not therapy. It’s all about (re)defining the experience and reality of a social group to justify dismantling public services (especially welfare), and that is form of gaslighting intended to extend oppressive political control and micromanagement. In linking receipt of welfare with health services and “state therapy,” with the single intended outcome explicitly expressed as employment, the government is purposefully conflating citizen’s widely varied needs with economic outcomes and diktats, isolating people from traditionally non-partisan networks of relatively unconditional support, such as the health service, social services, community services and mental health services.

Public services “speaking with one voice” will invariably make accessing support conditional, and further isolate already marginalised social groups. It will damage trust between people needing support and professionals who are meant to deliver essential public services, rather than simply extending government dogma, prejudices and discrimination.

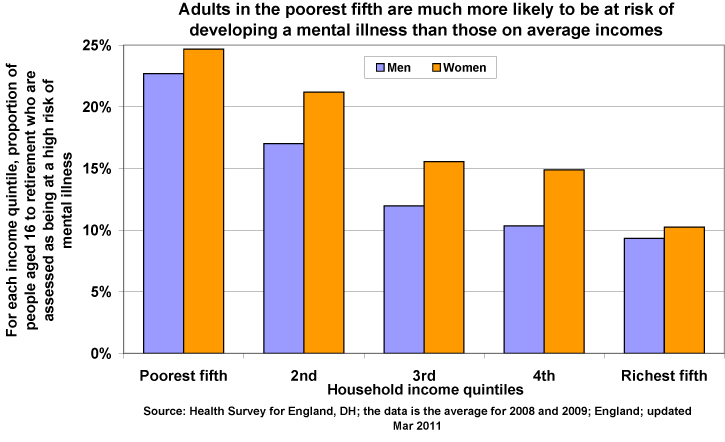

Conservatives really seem to believe that the only indication of a person’s functional capacity, value and potential is their economic productivity, and the only indication of their moral worth is their capability and degree of willingness to work. But unsatisfactory employment – low-paid, insecure and unfulfiling work – can result in a decline in health and wellbeing, indicating that it is poverty and growing inequality, rather than unemployment, that increases the risk of experiencing poor mental and physical health.

Moreover, in countries with an adequate social safety net, poor employment (low pay, short-term contracts), rather than unemployment, has the biggest detrimental impact on mental health.

There is ample medical evidence (rather than political dogma) to support this account. (See the Minnesota semistarvation experiment, for example. The understanding that food deprivation in particular dramatically alters cognitive capacity, emotions, motivation, personality, and that malnutrition directly and predictably affects the mind as well as the body is one of the legacies of the experiment.)

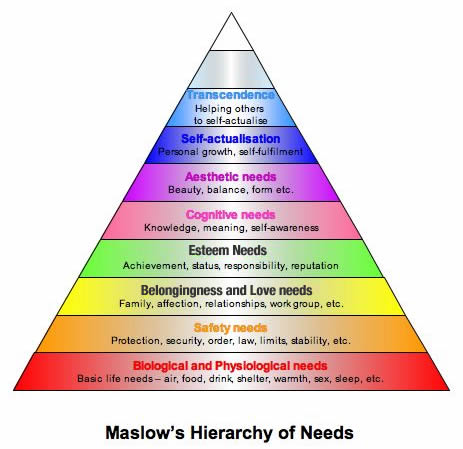

Systematically reducing social security, and increasing conditionality, particularly in the form of punitive benefit sanctions, doesn’t “incentivise” people to look for work. It simply means that people can no longer meet their basic physiological needs, as benefits are calculated to cover only the costs of food, fuel and shelter. Food deprivation is closely correlated with both physical and mental health deterioration. Maslow explained very well that if we cannot meet basic physical needs, we are highly unlikely to be able to meet higher level psychosocial needs. The government proposal that welfare sanctions will somehow “incentivise” people to look for work is pseudopsychology at its very worst and most dangerous.

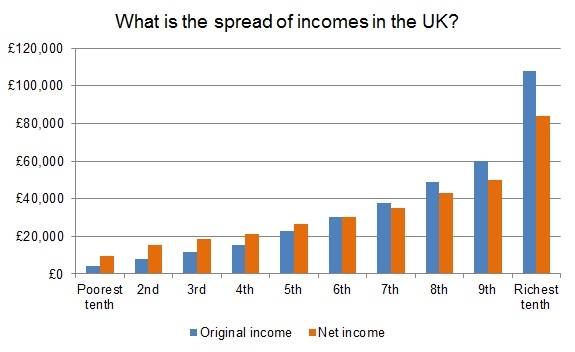

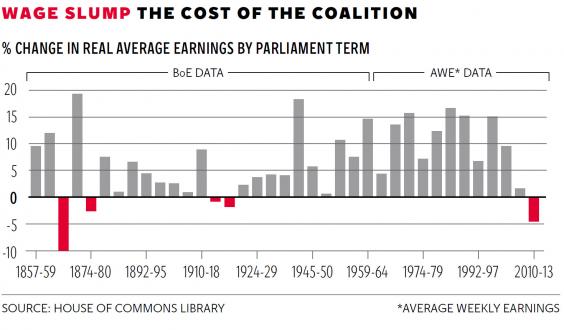

In the UK, the government’s welfare “reforms” have further reduced social security support, originally calculated to meet only basic physiological needs, which has had an adverse impact on people who rely on what was once a social safety net. Poverty is linked with negative health outcomes, but it doesn’t follow that employment will ameliorate poverty sufficiently to improve health outcomes. In fact record numbers of working families are now in poverty, with two-thirds of people who found work in 2014 taking jobs for less than the living wage, according to the annual report from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation a year ago.

Essential supportive provision is being reduced by conditionally, by linking it to such a narrow outcome – getting a job – and this will reduce every service to nothing more than a political semaphore, and service provision to a behaviour modification programme based on punishment, with a range of professionals being politically co-opted as state enforcers. The Government is intending to “signpost the importance of employment as a health outcome in mandates, outcomes frameworks, and interactions with Clinical Commissioning Groups.”

The fact that the Conservatives also plan to make receipt of benefits contingent on participation in “treatment” worryingly takes away the fundamental right of consent. I submitted a Freedom of Information request to the Department for Work and Pensions last year to ask for details of their methods of gaining claimant consent, their ethical framework and safeguards regarding the trialing of the new Work and Health programme. My request was rather unreasonably refused on the grounds of cost. I also sent the same request to the Cabinet Office, since the Behavioural Insights Team are involved in the design of the trials. Worryingly, the Office did not have the information.

Therapy in job centres and employment advisors in GP surgeries will not address inequality, and the social conditions that are the consequence of political decision-making and imposed economic frameworks, so it permits society to look the other way, whilst the government continue to present mental illness as an individual weakness or vulnerability, and a consequence of “worklessness” rather than a fairly predictable result of living in a highly unequal, competitive society, and arising because of experiences of living stigmatised, marginalised lives because of politically expedient policy-directed material deprivation.

Private firms like G4s, awarded multimillion-pound contracts to run the Work Programme, advised that there should be many more cases where claimants have their benefits stripped as punishment for failing to seek work. G4S earned £183m to help unemployed people to find work through the Government’s Work Programme. During the first eight months of the programme G4S asked benefit offices to sanction 7,780 claimants. In fact the company has effectively sanctioned many more people than it has “helped” into work.

There really should not be a role for G4S in the health service. G4S has left a wake of atrocities committed against vulnerable people in the UK and in other countries, including human rights abuses: exploitation, torture, causing deaths and forcing anti-psychotic injections on vulnerable prisoners to ensure they are passive and compliant.

Here is little information about G4S’s track record of working with vulnerable individuals and marginalised social groups, though this list is by no means exhaustive:

Human rights abuse allegations

Disabled ex-serviceman Peter McCormack, aged 79, was chained to a prison officer employed by G4S for eight days while in Royal Liverpool University Hospital after a heart attack in March 2012. The restraint was removed only briefly for him to take off his upper clothing, and when he was under heavy sedation undergoing an heart procedure. But he remained chained even when using the toilet and shower. McCormack, who has a disability as a result of being shot through the knee while serving with the Royal Engineers during the 1956 Suez crisis, spent 14 days attached by his wrist to a 2.5 metre closet chain, despite having been described as a model prisoner. Judge Graham Wood QC ruled in September 2014 that “During this time he was humiliated and his dignity was affronted.” Mr McCormack was detained because he may have faced a modest criminal sentence at most for breach of a regulatory offence in relation to his business.

McCormack was awarded £6,000 compensation for breach of his human rights. The judge criticised the evidence given by G4S’s then head of security, saying it was “less than impressive … It is a reasonable conclusion that she simply ignored a recommendation from a security manager.”

Unacceptable use of force by UK Border Agency

In October 2012 the Chief Inspector of Prisons, Nick Hardwick published his inspection report into the G4S-managed Cedars Pre-Departure Accommodation UK Border Agency (UKBA). G4S were criticised for using “non-approved techniques” during one particular incident in which a pregnant woman’s wheelchair was tipped up whilst her feet were held. The incident used “non-approved techniques” causing significant risk to the baby and was a “simply not acceptable” use of substantial force. Hardwick said: “There is no safe way to use force against a pregnant woman and to initiate it for the purpose of removal is to take an unacceptable risk.”

Significant force was also used against six out of the 39 families, including two children, at the centre, which holds families for up to a week, the report said.

Judith Dennis, of the Refugee Council, called for UKBA to heed the report’s recommendations, which include that force should only ever be used against pregnant women and children to prevent harm.

Jerry Petherick, managing director of G4S custodial and detention services, said the welfare of people in its care was its top priority.

The unlawful killing of Jimmy Mubenga

In October 2010, three G4S-guards restrained and held down 46-year-old Angolan deportee called Jimmy Mubenga on departing British Airways flight 77, at Heathrow Airport. Security guards kept him restrained in his seat as he began shouting and seeking to resist his deportation. Police and paramedics were called when Mubenga lost consciousness. The aircraft, which had been due to lift off, returned to the terminal. Mubenga was pronounced dead later that evening at Hillingdon hospital. Passengers reported hearing cries of “don’t do this” and “they are trying to kill me.” Scotland Yard’s homicide unit began an investigation after the death became categorised as “unexplained”. Three private security guards, contracted to escort deportees for the Home Office, were released on bail, after having been interviewed about the incident.

In February 2011, The Guardian reported that G4S guards in the United Kingdom had been repeatedly warned about the use of potentially lethal force on detainees and asylum seekers. Confidential informants and several employees released the information to reporters after G4S’s practices allegedly led to the death of Jimmy Mubenga. An internal document urged management to “meet this problem head on before the worst happens” and that G4S was “playing Russian roulette with detainees’ lives.” The following autumn, the company once again faced allegations of abuse. G4S guards were accused of verbally harassing and intimidating detainees with offensive and racist language.

In July 2012, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) announced its conclusion that there was “insufficient evidence to bring any charges for Mr Mubenga’s death” against G4S or any of its former employees. On 9 July 2013 an inquest jury, in a nine-to-one decision, found that Mubenga’s death was caused by the G4S guards “using unreasonable force and acting in an unlawful manner.”

Exploitation

In August 2014, G4S was again criticised for using immigrant detainees as cheap labour, with some being paid as little as £1 per hour. The Home Office defended the practice, and said: “The long-standing practice of offering paid work to detainees has been praised by Her Majesty’s inspectorate of prisons as it helps to keep them occupied whilst their removal is being arranged. Whether or not they wish to participate is entirely up to the detainees themselves. This practice is not intended to substitute the work of trained staff”

Abuse of vulnerable young people at Medway Secure Training Centre in Kent

A BBC Panorama investigation into abuse at a young offenders unit in Kent, run by security firm G4S, exposed child neglect and abuse. The Panorama programme provided shocking footage at Medway Secure Training Centre in Rochester following reports from a whistleblower. Shot by an undercover journalist who posed as a security officer, the footage shows staff using excessive force to restrain youngsters, bullying, lying when reporting incidents and boasting about hurting the inmates. The film shows a a senior officer restraining a 14-year-old boy by pressing his fingers on his throat.

One boy had injured himself by cutting his arm and staff piled on to restrain him, then left him in a cell crying, despite knowing that the boy’s mother had recently died and he was grieving. G4S employees boasted not only about harming children but also falsifying records so the company was not fined for losing control. Footage showed a vulnerable boy who was having his room cleared of anything he could harm himself with, was apparently choked and slammed on a bed.

The programme also revealed officers lying about incidents to cover up their actions.

G4S has been paid £140,000 per year per child held in Medway.

Among the allegations relating to ten boys aged 14 to 17, uncovered by Panorama and now subject to investigation are that Medway staff:

- Slapped a teenager several times on the head

- Pressed heavily on the necks and throats of young people

- Used restraint techniques unnecessarily – and that included squeezing a teenager’s windpipe so he had problems breathing

- Used foul language to frighten and intimidate – and boasted of mistreating young people, including using a fork to stab one on the leg and making another cry uncontrollably

- Tried to conceal their behaviour by ensuring they were beneath CCTV cameras or in areas not covered by them

South Africa prison torture and abuse accusations

In October 2013, the BBC reported that there are allegations of prisoners being tortured at Mangaung Prison in South Africa. The security firm G4S was given the contract to run the prison in 2000. The BBC cites research from the Wits Justice Project at Wits University in Johannesburg, claiming that dozens of the nearly 3,000 inmates at the G4S prison have been tortured using electroshock and forced injections. As of October 2013, G4S said it was investigating the allegations.

Leaked footage revealed that complaints of forced injections – that is, involuntary medication with powerful anti-psychotic drugs, with serious side effects, we true.

Emergency security team warders have further said that they would assist in administering forced injections up to five times a week.

Human rights abuse and violence at Manus Island Asylum Centre

G4S provided security in the Manus Island asylum processing centre in Papua New Guinea, and failed to maintain basic human rights standards and protect asylum seekers from harm, the complaint lodged to the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) alleged.

In 2008, Aboriginal elder, Mr Ward, cooked to death while being transported by G4S, more than 220 miles across searing Goldfields in a badly maintained van with faulty air conditioning in January 2008. He had third degree burns from contact with the searing hot metal floor of the van. The guards driving the prison van did not stop to check his welfare or see if he needed a toilet break, food or water until, they say, they heard a thud from the back. Even then they didn’t unlock both the cell doors, and instead threw water on Mr Ward through the chained-up inner door. The Department of Corrective Services, the prisoner transport contractor – G4S, and the prison van driver Graham Powell were also prosecuted by WorkSafe. Corrective Services and G4S were each fined $285,000 for their role in Mr Ward’s death. Mr Powell was fined $9000. Prison officer Nina Mary Stokoe was fined $11,000 for her role in the death of Mr Ward.

The Australian government nonetheless contracted G4S to oversee management and security at the Manus Island centre from February 2013 to March 2014, despite this.

Rachel Ball, the director of advocacy at the Human Rights Law Centre, said under government-endorsed OECD guidelines, multinational companies were obliged to respect human rights and avoid contributing to human rights abuses.

“In February this year G4S guards at the detention facility on Manus Island went on what can only be described as a violent rampage,” she said.

“Reza Berati was killed, one man lost his eye, another had his throat slit, and 77 others were treated for serious injuries including head wounds, a gunshot wound, broken bones and lacerations.

“G4S was directly involved in this violence through its role in arbitrary detention and poor conditions that led to the unrest, and through the direct participation of its employees in the violence.”

Ball said the company had not been held to account for its role in the violence, prompting the joint complaint between her organisation and the British non-government organisation Rights and Accountability in Development.

Conditions in the camp have also been strongly criticised by UN agencies and human rights groups.

Fraud allegations

In July 2013, British Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, asked the Serious Fraud Office to investigate G4S for overcharging for tagging criminals in England and Wales, claiming that it and rival company Serco charged the government for tagging people who were not actually being monitored, including tags for people in prison or out of the country, and a small number who had died. G4S was given an opportunity to take part in a forensic audit but initially refused.

Following the completion of a review by the Cabinet Office into major contracts across government, Francis Maude and the Cabinet Office announced in December 2013, that their review had “found no evidence of deliberate acts or omissions by either firm leading to errors or irregularities in the charging and billing arrangements on the 28 contracts investigated.”

In March 2014, G4S agreed to pay a settlement of £109 million to the government, incorporating a refund for “disputed” services and reimbursement of additional costs.

Scandal also followed G4S’s management of London Olympic security, back in 2012 when it failed to deliver enough guards to police the games. As a result 3,500 military troops were drafted in.

Despite these issues, G4S won significant new work for the British government in 2014 including selection by the Department for Work and Pensions to manage community work placement contracts, a deal providing healthcare services for prisons in the north east, and patient transport for the NHS.

G4S’s involvement in the recruitment of cognitive behavioural therapists to work with vulnerable unemployed people is a very worrying development.

Mindful of the company’s failure to fully investigate its ethical practices, RT compiled a list of past instances G4S has broken standards.

The Guardian: Outsourced services fail the vulnerable – “Red front doors in Middlesbrough, red wristbands in Cardiff. Not long ago another group of vilified people were also made to mark their doors and wear a distinctive badge – the yellow star. Who is advising Clearsprings?” And G4S. Dr Jonathan Fluxman

—

My work isn’t funded. But you can support Politics and Insights, and help me to continue researching, analysing and writing independently.