Illustration by Jack Hudson

The government’s Nudge Unit team is currently working with the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department of Health to trial social experiments aimed at finding ways of: “preventing people from falling out of the jobs market and going onto Employment and Support Allowance (ESA).”

“These include GPs prescribing a work coach, and a health and work passport to collate employment and health information. These emerged from research with people on ESA, and are now being tested with local teams of Jobcentres, GPs and employers.”

This is a crass state intrusion on the private and confidential patient-doctor relationship, which ought to be about addressing medical health problems, and supporting people who are ill, not about creating yet another space for obsessive political micromanagement. It’s yet another overextension of the coercive arm of the state to “help” people into work. Furthermore, this move will inevitably distort people’s interactions with their doctors: it will undermine the trust and rapport that the doctor-patient relationship is founded on.

In the current political context, where the government extends a brutally disciplinarian approach to basic social security entitlement, it’s very difficult to see how the plans to place employees from the Department for Work and Pensions in GP practices can be seen as anything but a threatening gesture towards patients who are ill, and who were, up until recent years, quite rightly exempted from working. Now it seems that this group, which includes some of our most vulnerable citizens, are being politically bullied and coerced into working, regardless of the consequences for their health and wellbeing.

Of course the government haven’t announced this latest “intervention” in the lives of disabled people. I found out about it quite by chance because I read Matthew Hancock’s recent conference speech: The Future of Public Services.

I researched a little further and found an article in Pulse which confirmed Hancock’s comment: GP practices to provide advice on job seeking in new pilot scheme.

Hancock is appointed Minister for the Cabinet Office and Paymaster General, and was previously the Minister of State for Business and Enterprise. He headed David Cameron’s “earn or learn” taskforce which aims to have every young person earning or “learning” from April 2017.

He announced that 18 to 21-year-olds who can’t find work would be required to do work experience (free labour for Tory business donors) as well as looking for jobs or face losing their benefits. But then Hancock is keen to commodify everyone and everything, including public data.

However his references to “accountability and transparency” don’t stand up to much scrutiny when we consider the fact that he recently laid a statement before parliament outlining details about the five-person commission that will be asked to decide whether the Freedom of Information act is too expensive and “overly intrusive.”

He goes on to say: “And this brings me onto my second area of reform: experimentation. Because in seeking to improve our services, we need to know what actually works.”

But we need to ask for whom services are being “improved” and for whom does such reform work, exactly?

And did any of the public actually consent to being experimented upon by the state?

Or to having their behaviour modified without their knowledge?

Now that the nudge unit has been privatised, it is protected from public scrutiny, and worryingly, it is also no longer subject to the accountability afforded the public by the Freedom of Information Act.

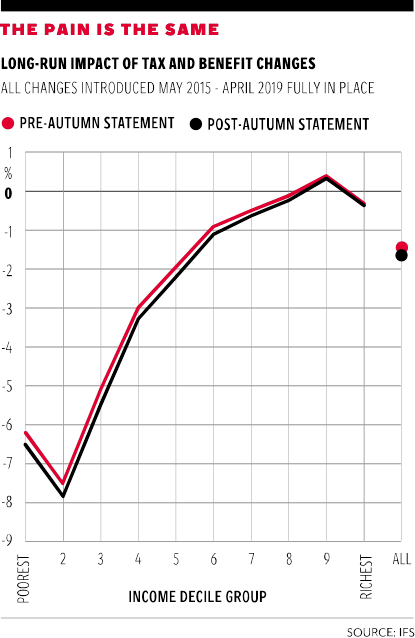

The Tory welfare “reforms” are a big business profiteering opportunity, whilst lifeline benefits are being steadily withdrawn: policy context

The current frame of reference regarding Conservative welfare policies is an authoritarian and punitive one. It’s inconceivable that a government proposing to continue cutting the lifeline income of sick and disabled people, including a further £120 a month to those people in the ESA Work Related Activity group (WRAG), will suddenly show an interest in actually supporting disabled people. There are also proposals to further limit eligibility for Personal Independence Payments (PIP) for sick and disabled people.

From the shrinking category of legitimate “disability” to forcing people to work for no pay on exploitative workfare schemes, “nudge” has been used to euphemistically frame punitive policies, “applying the principles of behavioural economics to the important issue of the transition from welfare to work.” (From: Employing BELIEF: Applying behavioural economics to welfare to work, 2010.)

And guess who sponsored the “research” into “nudging” people into workfare? Steve Moore, Business Development Director from esg, which is “a leading welfare to work and vocational skills group, created through the merger and acquisition of four leading providers in the DWP and LSC sector.” How surprising.

It’s even more unsurprising that esg was established by two Conservative donors with very close ties to ministers, and were subsequently awarded very lucrative contracts with the Department for Work and Pensions. I think there may have been a “cognitive bias” in operation there, too. But who is nudging the nudgers?

Of course the “aim” of the “research” is: “breaking the cycle of benefit dependency especially for our hardest to help customers, including the “cohort” of disabled people.”

However, there’s no such thing as a “cycle of benefit dependency”, it’s a traditional Tory prejudice and is based on historically unevidenced myths. Poverty arises because of socioeconomic circumstances that are unmitigated through government decision-making. In fact this government has intentionally extended and perpetuated inequality through its policies.

2020health – Working Together is a report from 2012 that promotes the absurd notion of work as a health outcome. This is a central theme amongst ideas that are driving the fit for work and the work and health and programme. Developing this idea further, Dame Carol Black and David Frost’s Health at Work – an independent review of sickness absence was aimed at reviewing ways of “reducing the cost of sickness to employers, ‘taxpayers’ and the economy.” Seems that the central aim of the review wasn’t a genuine focus on sick and disabled people’s wellbeing and “health outcomes,” then. Black and Frost advocated changing sickness certification to further reduce the influence of GPs in “deciding entitlement to out-of-work sickness benefits.”

The subsequent “fit notes” that replaced GP sick notes (a semantic shift of Orwellian proportions) were designed to substantially limit the sick role and reduce recovery periods, and to “encourage” GPs to disclose what work-related tasks patients may still be able to perform. The idea that employers could provide reasonable adjustments that allowed people who are on sick leave to return to work earlier, however, hasn’t happened in reality.

The British Medical Association (BMA) has been highly critical of the language used by the government when describing the fit for work service. The association said it was “misleading” to claim that fit for work was offering “occupational health advice and support” when the emphasis was on sickness absence management and providing a focused return to work.

The idea that work is a “health” outcome is founded on an absurd and circular Conservative logic that people in work are healthier than those out of work. It’s true that they are, however, the government have yet again confused causes with effects. Work does not make people healthier: it’s simply that healthy people can work and do. People who have long term or chronic illnesses often can’t work. The government’s main objection to sick leave and illness more generally, is that it costs businesses money. As inconvenient as that may be, politically and economically, it isn’t ever going to be possible to cure people of serious illnesses by cruelly coercing them into work.

The government’s removal of essential in-work support for disabled people – such as the Independent Living Fund, and the replacing of Disability Living Allowance with Personal Independence Payment in order to reduce eligibility, cut costs and “target” support to those most severely disabled, and the cuts to the Access To Work scheme – means that it is now much more difficult for those disabled people who want to work to find suitable and supported employment.

The politics of punishment

There’s a clear connection between the Nudge Unit’s obsession with manipulating “cognitive bias” – in particular, “loss aversion” – and the increased use, extended scope and severity of sanctions, though most people succumbing to the Nudge Unit’s guru effect (ironically, another cognitive bias) think that “nudging” is just about prompting men to pee on the right spot in urinals, or persuading us to donate organs and to pay our taxes on time.

When it comes to technocratic fads like nudge, it’s worth bearing in mind that truth and ethics quite often have an inversely proportional relationship with the profit motive.

For anyone curious as to how such tyrannical behaviour modification techniques like benefit sanctions arose from the bland language, inane, managementspeak acronyms and pseudo-scientific framework of “paternal libertarianism” – nudge – read this paper, focused almost exclusively on New Right obsessions, paying particular attention to the part about “loss aversion” (a cognitive bias according to behavioural economists) on page 7.

And this on page 18: “The most obvious policy implication arising from loss aversion is that if policy-makers can clearly convey the losses that certain behaviour will incur, it may encourage people not to do it,” and page 46: “Given that, for most people, losses are more important than comparable gains, it is important that potential losses are defined and made explicit to jobseekers (e.g.the sanctions regime).”

The recommendation on that page: “We believe the regime is currently too complex and, despite people’s tendency towards loss aversion, the lack of clarity around the sanctions regime can make it ineffective. Complexity prevents claimants from fully appreciating the financial losses they face if they do not comply with the conditions of their benefit.”

The Conservatives duly “simplified” sanctions by extending them in terms of severity, frequency and by broadening the scope of their application to include previously protected social groups.

The paper was written in November 2010, prior to the Coalition policy of increased “conditionality” and extended sanctions element of the Tory-led welfare “reforms” in 2012.

Sanctioning welfare recipients by removing their lifeline benefit – originally calculated to meet the cost of only basic survival needs – food, fuel and shelter – isn’t about “arranging choice architecture”, it’s not nudging: it’s operant conditioning. It’s a brand of particularly dystopic, psychopolitical neobehaviourism, and is all about a totalitarian level of micromanaging people to ensure they are obedient and conform to meet the needs of the “choice architects” and policy-makers.

Nudge even permeates language, prompting semantic shifts towards bland descriptors which mask power and class relations, coercive state actions and political intentions. One only need to look at the context in which the government use words like “fair”, “support”, “help” “justice” and “reform” to recognise linguistic behaviourism in action. Or if you prefer, Orwellian doublespeak.

It’s rather difficult to see how starving people and threatening them with destitution can possibly “improve the well-being of many socially excluded people, and help to bring them to inclusion.”

The conclusion that Ancel Keys drew from the Minnesota Starvation Experiment in the the US during the 1940s, (which explored the physical and psychological effects of undernutrition, and stressed the dramatic, adverse effect that starvation had on competence, motivation, behaviour, mental attitude and personality) was that “democracy and nation building would not be possible in a population that did not have access to sufficient food.”

No amount of bland and meaningless psychobabble or intransigent, ideologically-tainted policies can legitimize the economic sanctioning of people who are already poor and in need of financial assistance.

Apparently, citizenship and entitlement to basic rights and autonomy is a status conferred on only the currently economically productive. Previous employment and contributions don’t count as “responsibility,” and don’t earn you any rights – the government believes that citizens owe a perpetual debt of unconditional service to the Conservative’s steeply stratified economy. Not much of a social contract, then. Cameron says he wants to “build a responsible society” by removing people’s rights and reducing or removing their lifeline income. Presumably, free invisible bootstraps are part of the deal.

Government decision-making has contributed the most significant influence on “health outcomes.” Conservative policies have entailed a vicious cutting back of support and a reduction of essential provision for sick and disabled people. In fact this group have been disproportionately targeted for austerity cuts time and time again, massively reducing their lifeline income. It’s not being “workless” that has a detrimental impact on people’s health and wellbeing: it is the deliberate impoverishment of those requiring state aid and support, funded from the public purse, (including contributions from those who now need support), which is being dogmatically and steadily withdrawn.

Making work pay for whom?

If work truly paid, then there would be no need to “incentivise” almost 1.2 million low-paid workers claiming the new universal credit with the threat of in-work benefit sanctions if they fail to “take steps to boost their earnings.”

It’s very difficult to see how punishing individuals for perhaps being too ill to work more that a few hours, or those working for low pay or part-time in the context of a chronically weak labour market, depressed wages and with little scope for effective negotiating and collective bargaining can possibly be justified. It’s an utterly barbaric way for a government to treat citizens.

Surely if the government was genuinely seeking to increase choices and to widen access to the workplace for sick and disabled people, it would not be cutting the very programmes supporting and extending this aim, such as the Access to Work scheme – a fund that helps people and employers to cover the extra living costs arising due to disabilities that might present barriers to work – and the Independent Living Fund.

This government has pushed at the public’s rational and moral boundaries, establishing and attempting to justify a draconian trend of punishing those unable to work, and what was previously unthinkable – stigmatising and punishing legally protected social groups such as sick and disabled people – has become somehow acceptable. We are on a very slippery slope, clearly mapped out previously by Allport’s scale of prejudice.

People’s needs don’t disappear just because the government has decided to “pay down” an ever-growing debt and build a “surplus” by taking money from those that have the least. Or because the government doesn’t like “big state interventions.”

So the recent proposed cut to ESA – and this is a group of sick and disabled people deemed physically incapable of work by doctors – is completely unjustified and unjustifiable. No amount of pseudo-psychology and paternalist cruelty can motivate or “incentivise” people who are medically ill.

It’s for disabled individuals and their doctors – professionals, specialists and experts – to decide if a person can work or not, it’s not the role of the state, motivated only by a perverse economic Darwinist ideology. Maslow taught us that we must attend to our physiological needs before we may be motivated to meet higher level psychosocial ones.

Iain Duncan Smith is a zealot who actually tries to justify further punitive cuts to disabled people’s provision by claiming that working is “good” for people and is the only “route out of poverty.”

Presumably he believes work can cure people of the serious afflictions that they erroneously thought exempted them from full-time employment.

He stated: “There is one area on which I believe we haven’t focused enough – how work is good for your health. Work can help keep people healthy as well as help promote recovery if someone falls ill. So, it is right that we look at how the system supports people who are sick and helps them into work.”

Duncan Smith undoubtedly “just knows” that his absurd claim is “right.” He’s never really grown out of his “magical thinking” stage, or transcended his dereistic tendencies. His department had to manufacture “evidence” recently in a ridiculous attempt to support Iain Duncan Smith’s imaginative, paternalist claim that punitive sanctions are somehow “beneficial” to claimants, by using fake characters to supply fake testimonials, but this was rumbled and exposed by a well-placed Freedom of Information request from Welfare Weekly.

Recent research indicates that not all work serves to “keep people healthy” nor does it ever “promote recovery.” This assumption that work can promote recovery in the case of people with severe illness and disability – which is why people claim ESA – is particularly bizarre. We have yet to hear of a single case involving a job miracle entailing people’s limbs growing back, vision being restored, or a wonder cure for heart failure, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis and lupus, for example.

The government’s Fit for Work scheme is founded on exactly the same misinformative nonsense. It supports profit-making for wealthy employers, at the expense of the health and wellbeing of employees that have been signed off work because of medically and professionally recognised illness that acts as a real barrier to work.

Furthermore, there is no proof that work in itself is beneficial. Indeed much research evidence strongly suggests otherwise.

And where have we heard these ideas from Iain Duncan Smith before?

Arbeit macht frei.

If work really paid then surely there would be no need to “nudge” people by using sanctions, regardless of whether or not they are employed. “Making work pay” is all about reducing support for those who the government deems “undeserving,” to “discourage welfare dependency” by making any support as horrible as the workhouse – founded on the principle of “less eligibility”, where conditions for those in need of support were punitive and kept people in a state of desperation so that even the lowest paid work in the worst of conditions would seem appealing.

The public/private divide

For a government that claims a minarchist philosophy, remarkably it has engineered an unprecedented blurring of public/private boundaries and a persistent violation of traditionally private experiences, including thoughts, beliefs, preferences, autonomy and attitudes via legislations and of course a heavy-handed fiscal conflation of public interests with private ones.

This also caught my attention from Matthew Hancock’s speech transcript:

“My case is that we need continuous improvement in public services. And for that we must reform the relationship between citizen and state. [My bolding]

“The case for reform is strong. Because people have high and rising expectations about what our public services should deliver. Because budgets are tight, and we have to make significant savings for our country to live within her means.”

Basically, the “paternalistic libertarian” message here is that we will have to expect less and less from the state, as the balance between rights and responsibilities is heavily weighted towards the latter, hence requiring the “reform” of the relationship between citizen and state.

However, surely it is active, democratic participation in processes of deliberation and decision-making that ensures that individuals are citizens, not subjects.

Social democracy evolved to include the idea of access to social goods and improving living standards as a means of widening and legitimizing the scope of political representation.

Political policies are defined as (1) The basic principles by which a government is guided. (2) The declared objectives that a government seeks to achieve and preserve in the interest of national community. As applied to a law, ordinance, or Rule of Law, it’s the general purpose or tendency considered as directed to the welfare or prosperity of the state or community.

Once upon a time, policy was a response from government aimed at meeting public needs. It was part of an intimate democratic dialogue between the state and citizens. Traditional methods of participating in government decision-making include:

- political parties or individual politicians

- lobbying decision makers in government

- community groups

- voluntary organisations

- public opinion

- public consultations

- the media

Nowadays, policies have been unanchored from any democratic dialogue regarding public needs and are more about monologues aimed at shaping those needs to suit the government.

Nudge does not entail citizen involvement in either its origin or design. The state intrusions are at such an existential level, of an increasingly authoritarian nature, and are of course reserved for the poorest, who are deemed “irrational” and incapable of making “the right decisions.”

Yet those “faulty decisions” are deemed so from the perspective of the Behavioural Insights Team, (the “Nudge Unit”) who are not social psychologists: they are predominantly concerned with behavioural economics, decision-making and how governments influence people – “economologists”, changing people’s behaviours, enforcing compliance to fulfil political aims. That turns democracy completely on its head.

The Nudge Unit gurus claim that we need help to “correct our cognitive biases”, but those who make policies have their own whopping biases, too.

Nudge is the new fudging

Nudge is a prop for New Right neoliberal ideology that is aimed at dismantling a rights-based society and replacing it with an insidiously nudged, manipulated, compliant, and entirely “responsible”, “self-reliant” population of divided, isolated state-determined individuals who expect nothing from their elected government.

The Conservatives are obsessive about strict social taxonomies and economic enclosures. The Nudge Unit was set up by David Cameron in 2010 to try to “improve” public services and save money. The asymmetrical, class-contingent application of paternalistic libertarian “insights” establishes a hierarchy of decision-making “competence” and autonomy, which unsurprisingly corresponds with the hierarchy of wealth distribution.

So Nudge inevitably will deepen and perpetuate existing inequality and prejudice, adding a dimension of patronising psycho-moral suprematism to add further insult to politically inflicted injury. Nudge is a fashionable fad that is overhyped, trivial, unreliable; a smokescreen, a prop for neoliberalism and monstrously unfair, bad policy-making.

As someone who (despite the central dismal and patronising assumptions about the irrationality of others that king nudgers have as a central cognitive bias and the traditional prejudices that Tory ideology narrates,) manages to make my own decisions relatively without bias, intelligently, rationally, critically, carefully and coherently, and that, along with my professional and academic background, I can and will conclude that no matter how you dress it up, nudge is a pretentious, cringeworthy pseudo-intellectual dead-end.

A Nudge for the Conservatives from history

The more things change for the Tories, the more they tend to stay the same.

In the 1870s, England had a recession and the Conservatives launched a Crusade of cuts to welfare expenditure to diminish “dependency” on poor law outdoor relief – non-institutional benefits called “out-relief” because it was paid to the poor in their own homes from taxation, rather than their having to go into the punitive “deterrent” workhouses.

The Crusade included cutting medical payments to lone mothers, widows, the elderly, chronically sick and disabled people and those with mental illness. The 1834 Poor Law amendment was shaped by people such as Jeremy Bentham, who argued for a disciplinary, punitive approach to social problems and particularly poverty, whilst Thomas Malthus focused attention on overpopulation, and moralising about the growth of illegitimacy. He placed emphasis on moral restraint rather than poor relief as the best means of easing the poverty of the lower classes.

David Ricardo argued that there was a problem with poor relief provision “interfering” with an iron law of wages. Ricardo claimed that aid given to poor workers under the old Poor Law to supplement their wages had the effect of undermining the wages of other workers, so that the Roundsman System and Speenhamland system led employers to reduce wages, and needed reform to help workers who were not getting such aid and rate-payers whose poor-rates were going to subsidise low-wage employers. Yet we found, despite Ricardo’s pet theory, that the poor law deterrent element served to push wages down further.

The effect of poor relief, in the absurd view of the reformers, was to undermine the position of the “independent labourer.” They also wanted to “make work pay.” And end the “something for nothing” culture. But much subsequent evidence shows that reducing support for people out of work actually drives wages and working conditions down.

Neither the punitive poor law amendment act of 1834 or the Crusade “helped” people into work or addressed the lack of available paid work – that’s unemployment, not the made-up and intentionally stigmatizing word “worklessness”.

And its utter failure as a credible account of poverty – the-blame-the-individual narrative and the notion that relief discourages “self-reliance” – fuelled the national insurance act of 1911 and the development of the welfare state along with the other civilising and civilised benefits of the post-war settlement.

The Conservatives inadvertently taught us as a society precisely why we need a welfare state.

We learned that it isn’t possible to be “thrifty” or help ourselves if we haven’t got the means for meeting basic survival needs. Nor is it possible to be nudged out of poverty when the means of doing so are not actually available. No amount of moralising and pseudo-psychologising about poor people actually works to address poverty, and structural socioeconomic inequalities.

The government’s undeclared preoccupation with behavioural change through personal responsibility is simply a revamped version of Samuel Smiles’s bible of Victorian and over-moralising, a hobby-horse: “thrift and self-help” – but only for the poor, of course. Smiles and other powerful, wealthy and privileged Conservative thinkers, such as Herbert Spencer, claimed that poverty was caused largely by the irresponsible habits of the poor during that era. But we learned historically that socioeconomic circumstances caused by political decision-making creates poverty.

Conservative rhetoric is designed to have us believe there would be no poor people if the welfare state didn’t somehow “create” them. If the Tories must insist on peddling the myth of meritocracy, then surely they must also concede that whilst such a system has some beneficiaries, it also creates situations of insolvency and poverty for others.

In other words, the same system that allows some people to become very wealthy is the same system that condemns others to poverty.

This wide recognition that the raw “market forces” of the old liberal laissez-faire (and the current starker neoliberalism) causes casualties is why the welfare state came into being, after all – because when we allow such competitive economic dogmas to manifest, there are invariably winners and losers.

That is the nature of “competitive individualism,” and along with inequality, it’s an implicit, undeniable and fundamental part of the meritocracy myth and neoliberal script. And that’s before we consider the fact that whenever there is a Conservative government, there is no such thing as a “free market”: in reality, all markets are rigged for elites.

Public policy is not an ideological tool for a so-called democratic government to simply get its own way. Democracy means that the voices of citizens, especially members of protected social groups, need to be included in political decision-making, rather than so frankly excluded.

We elect governments to meet public needs, not to “change behaviours” of citizens to suit government needs and prop up policy “outcomes” that are driven entirely by traditional Tory prejudice and ideology.

And by the way, we call any political notion that citizens should be totally subject to an absolute state authority “totalitarianism,” not “nudge.”

Courtesy of Robert Livingstone

Update: The government have since announced the introduction of a number of “policy initiatives” aimed at reducing the number of people claiming Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). These initiatives are currently still at a research and trialing stage. Health Management, a subsidiary of MAXIMUS are to deliver the fit for work programme, which was set up based on recommendations from the Health at Work – an independent review of sickness absence report by Dame Carol Black and David Frost. The review was aimed at “reducing the cost of sickness to employers, ‘taxpayers’ and the economy.”

Fit for Work occupational health professional will have access to people’s diagnoses from their fit notes, the fit note end date and any further information that the GP considers relevant to their absence from work or current treatment (at the discretion of the GP). The primary referral route for an assessment for the Maximus programme will be via the GP.

The government is cutting funding for contracted-out employment support by 80%, following the Spending Review. The Department for Work and Pensions has indicated that total spending on employment will be reduced, including not renewing Mandatory Work Activity and Community Work Placements, the new Work and Health Programme will have funding of around £130 million a year – around 20% of the level of funding for the unsuccessful Work Programme and Work Choice, which it will replace.

Iain Duncan Smith says: “This Spending Review will see the start of genuine integration between the health and work sectors, with a renewed focus on supporting people with health conditions and disabilities return to and remain in work. We will increase spending in this area, expanding Access to Work and Fit for Work, and investing in the Health and Work Innovation Fund and the new Work and Health Programme.”

Meeting the Government’s goal of halving the employment gap between disabled and non-disabled workers – moving around one million more disabled people into work – will be no easy task. Not least because despite Iain Duncan Smith’s ideological commitments, and aims to “reduce welfare dependency,” most disabled people who don’t work (and claim ESA) can’t do so because of genuine and insurmountable barriers such as incapacitating and devastating, life-changing illness. No amount of targeting those people with the Conservative doublespeak variant of “help” and nasty “incentivising” via welfare sanctions and benefit cuts will remedy that.

—